Nutritional Assessment

Samuel Sandowski MD

The old adage “you are what you eat” is a mainstay of nutritional education. This chapter will elaborate on the importance of nutrition in primary care as well as explain the methodology and techniques used in assessing nutritional status and prescribing diets. As with all aspects of primary care, nutrition must be individualized. Cultural, religious, economic, and social values must be accounted for in nutrition evaluations.

IMPORTANCE OF NUTRITION IN PRIMARY CARE

Nutritional assessment is an integral part of the primary care provider’s role. In addition to assessing the patient’s overall nutritional status, the provider must also identify any existing or potential deficiency states. Total calorie malnutrition (marasmus) or protein calorie deficiency alone (kwashiorkor) may be seen. Patients may be deficient in only one nutrient, vitamin, mineral, or essential element. These deficiencies are often first noted and addressed by the primary care provider.

Patients’ concerns must also be addressed. A patient with a desire to lose weight and start an exercise program is a common scenario in “health-conscious America.” The patient who asks the provider if it is “okay” to have his or her family on a vegetarian diet is quite common too.

Food faddisms are constantly changing. Patients often approach their providers with questions such as “Is garlic really healthy?” or “Will vitamin E prevent aging and cancer?” Providers must also be familiar with the latest antiobesity and anorectic medications, especially if the media informs the public before the medications are FDA-approved.

Providers must counsel patients about specific illnesses. Diabetes mellitus, hypertension, coronary artery disease, renal disease, liver disease, obesity, anemia, gastrointestinal disturbances, and hypercholesterolemia are but a few disease states in which nutrition is intimately related to both the disease process and the treatment. Nutritional factors are the second leading cause of preventable deaths in the United States (cigarette smoking is the first) (McGinnis & Foese, 1993).

Patients often take supplements without the provider’s knowledge. Supplementation refers to extra sources (ie, outside standard diet) for nutrition, whether it be vitamins and minerals, high-calorie shakes, or even parenteral nutrition. Many vitamins in excess are excreted in the urine, but overdoses and megadoses of the fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) are potentially toxic. Excess of minerals may be toxic as well.

NUTRITIONAL ASSESSMENT

The basic parts of the nutritional assessment include the history, the physical exam, laboratory studies, and calculation of the patient’s needs. The difficult part is finding an appropriate prescription, one that reflects the patient’s physical needs as well as their willingness and ability to participate.

The Dietary History

The dietary history is part of a comprehensive history. It includes several aspects of the patient’s life, reflecting the biopsychosocial model of health care in addition to the actual food intake.

BIOLOGIC

This part of the history should include hard-core medical data including age, gender, allergies, medical illnesses, and past surgeries. In addition, usual weight and recent weight changes should be included, as should recent changes in appetite, as well as past patterns of dieting. Bowel patterns, dentition, dysphagia, and current medications should be inquired about as well. Use of supplements, vitamins, and herbs must also be explored.

PSYCHOSOCIAL

Psychosocial factors are critical to assessing both nutritional status and the patient’s ability to make changes in their diet. These include questions such as where and with whom does the patient eat? Who does the shopping and who prepares the food? Can the patient afford to buy foods different than those he or she currently purchases? What religious dietary restrictions and cultural preferences apply?

Food Intake Records

There are several methods to evaluate a patient’s food intake. Three common ways are 24-hour food recall, food diaries, and food frequency questionnaires. Each method can be useful, but because each has flaws, a combination of these three methods may be recommended.

The 24-hour food recall requires the patient to remember, or recall what has been eaten over the past 24 hours. This is often done by the patient describing the last things eaten first and working backwards. Foods and beverages, methods of preparation, and portion sizes must be noted. Though this is a quick and easy method, a one-day history may not be representative of the patient’s usual diet. Multiple 24-hour food recalls, however, may be more accurate than a food diary (Buzzard et al, 1996).

The food diary, an accurate method of evaluating a patient’s intake, may be rather cumbersome and time-consuming. The patient writes down all that he or she eats and drinks over a given number of days. Again, portion sizes and methods of

preparation must be noted. It is true that the patient may change eating patterns while maintaining a food record, but then again, does this mean we have succeeded in having our patients educated and change their eating behaviors?

preparation must be noted. It is true that the patient may change eating patterns while maintaining a food record, but then again, does this mean we have succeeded in having our patients educated and change their eating behaviors?

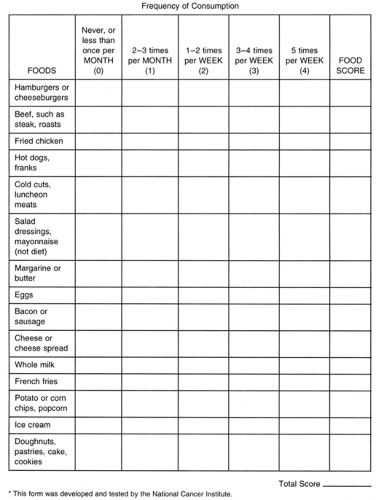

Food frequency questionnaires will question the patient about how often they eat certain foods. This may identify potential deficiencies in a particular food group. However, portion sizes (described below) are often not accounted for or understood by the person completing the questionnaire. Also, if a food that a patient usually eats is not listed, this will skew the results. For example, when trying to assess fat consumption, asking the patient how often they eat cakes and ice cream, but not asking about chocolates, will not accurately reflect fat intake. An example of a food frequency questionnaire is shown in Figure 5-1.

Exchange Lists and Portion Sizes

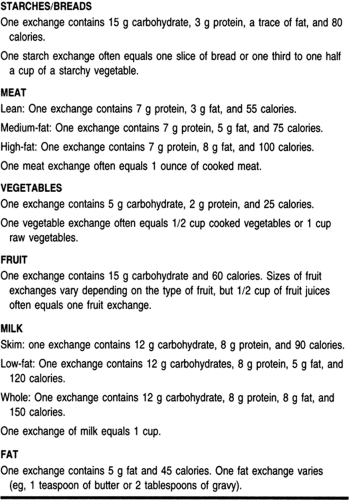

The American Dietetic Association has a list of food exchanges. The list includes foods grouped into the following food groups:

starches/breads, meats, vegetables, fruits, milk/dairy and fats (Table 5-1). An exchange is a measured amount of food that would be of equal caloric value as another food in that same group. For example, one exchange from the starch/breads group is equal to 80 kcal. Therefore, one slice of bread or half a cup of cooked pasta are each one exchange, or 80 kcal. Based on the number and type of exchanges one eats, the total calories as well as the amount of carbohydrate, protein, and fat consumed can be calculated.

starches/breads, meats, vegetables, fruits, milk/dairy and fats (Table 5-1). An exchange is a measured amount of food that would be of equal caloric value as another food in that same group. For example, one exchange from the starch/breads group is equal to 80 kcal. Therefore, one slice of bread or half a cup of cooked pasta are each one exchange, or 80 kcal. Based on the number and type of exchanges one eats, the total calories as well as the amount of carbohydrate, protein, and fat consumed can be calculated.

Portion sizes refer to the amount a patient eats of a particular food. A portion size in many diet plans does not necessarily mean one food exchange; often a portion of meat is equal to about 3 meat exchanges. A quick and easy way to estimate appropriate portion sizes is using a fistful (about half a cup) and palm size (about 3 meat exchanges).

Physical Examination

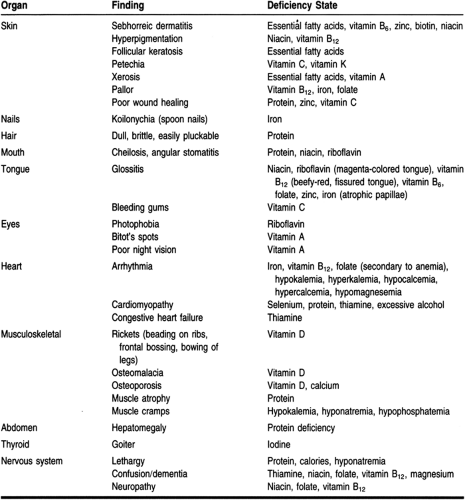

The physical examination is as important as a good history. Height and weight must be recorded. Weight alone is an incomplete assessment. A 5′ tall woman weighing 100 pounds may be appropriate. However, a 6′ tall male at this weight would be grossly malnourished. For a complete nutritional assessment, a complete physical must be done. The provider must note the hair, skin, eyes, mouth, tongue, teeth, glands, nails, heart, abdomen, bones and joints, and muscles of the extremities and must perform a complete neurologic exam (Table 5-2).

Laboratory Studies

Many different laboratory values are used as potential nutritional assessors. Often looked at are albumin and cholesterol. Both of these tend to fall when patients become malnourished. However, these are not pathognomonic for nutritional deficiencies. Some people tend to have low total cholesterol levels without any deficiencies. In addition, total cholesterol levels may fall with disease states regardless of nutritional status. Albumin too tends to fall with acute stress and trauma, as well as with certain diseases, such as protein-losing enteropathies and nephropathies. Prealbumin, which has a shorter half-life than albumin, may be a better tool to assess the patient’s prognosis and nutritional state (Bernstein & Pleban, 1996; Mears, 1996). Transferrin, another acute-phase reactant also may be useful in assessing nutritional status and is one of the factors in calculating the prognostic nutritional index (PNI), an assessment tool used in helping predict prognosis, morbidity, and mortality of preoperative patients.

Another laboratory value often considered is the complete blood count (CBC). Anemia may reflect an iron-deficient state if the mean corpuscular volume (MCV) is low. If the MCV is elevated, this may represent deficiency in vitamin B12 or folate, or it may suggest alcoholism. A low lymphocyte count may reflect malnutrition. Deficiency in vitamin K prolongs the prothrombin time (PT) (ie, increase the INR), and bleeding time is prolonged with vitamin C deficiency. Direct screening for specific vitamin deficiencies are not done routinely and should be obtained only if there is a high index of suspicion.

Calculations

IDEAL BODY WEIGHT

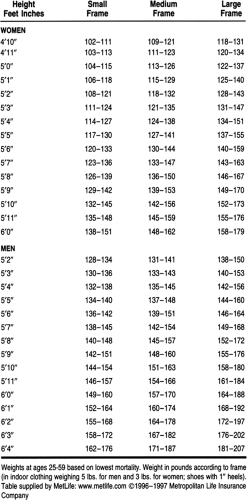

Once patients have been assessed, their nutritional needs must be calculated. An ideal body weight (IBW) is calculated based on a person’s gender, height and body frame. These IBWs were set by Metropolitan Life Insurance Company (Table 5-3) using a select cohort, and this should noted when addressing patients. A simple bedside calculation for IBW for men can be calculated as follows: Ideal body weight = 106 lbs for the first 5′ and 6 lbs for each additional inch. For women, the formula is: ideal body weight = 100 lbs for the first 5′ and 5 lbs for each additional inch. These are for medium frame adults and should be adjusted plus or minus 10% for larger or smaller body frames.

In bed-ridden, elderly, or kyphotic patients who have difficulty standing erect, the patient’s height can be calculated measuring the knee height. The knee height is the distance, in centimeters, from the bottom of the foot to the top of the knee (ie, distal femur) when the knee is flexed at 90 degrees. The formula for knee height is:

Men:

Ht (cm) = 64.19—(0.04 × age) + (2.02 × knee height)

Women:

Ht (cm) = 84.88—(0.24 × age) + (1.83 × knee height)

BODY FRAME

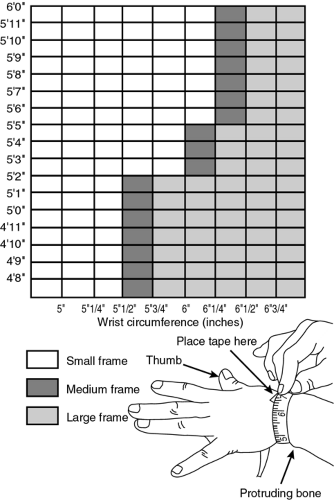

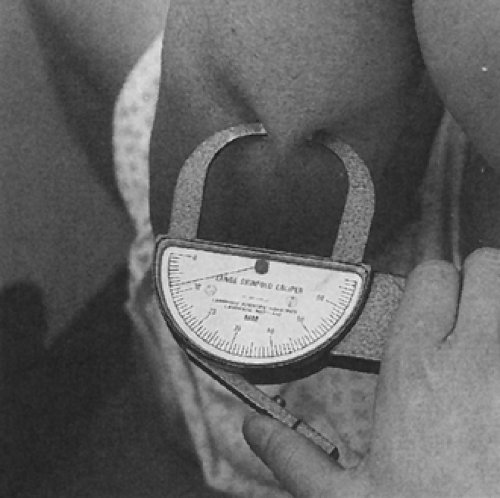

Body frame is measured by bone width. Using calipers, the widest point between the medial and lateral condyles of the elbow is measured. Others use wrist circumference to assess

body frame. Tables for elbow breadth and wrist circumference have been established, taking into account height (Fig. 5-2).

body frame. Tables for elbow breadth and wrist circumference have been established, taking into account height (Fig. 5-2).

ADJUSTED BODY WEIGHT

Adjusted body weight (ABW) is a technique used to personalize IBW. Goals of weight change become more realistic, taking into account the patient’s present weight. The formula for adjusted body weight is: ABW = ([present body weight − ideal body weight]/4) + ideal body weight.

BODY MASS INDEX

Body mass index (BMI) is a value based on both weight and height. It is equal to weight/height2 in kg/m2. Often considered “ideal” is a BMI of 19–25 (National Center for Health Statistics, 1995). A BMI of more than 27.8 for men and 27.3 for women may increase the risk of morbidity and mortality.

BODY FAT ESTIMATES

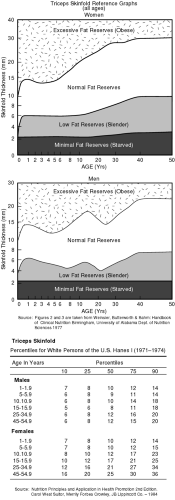

It is worthwhile to note that a person’s height and weight alone may still not be enough for assessment. With recent fads in body building and steroid abuse, certain patients may be “overweight” based on ideal body weight, but they may have a low percentage of total body fat. Body composition can be measured by many sophisticated techniques, but simple bedside calculations can be measured by midarm circumference and triceps and subscapular skin folds. The midarm circumference is the circumference, in centimeters, of the left arm, halfway between the elbow and shoulder, with the arm fully extended. The triceps skin fold is measured by separating the skin and the subcutaneous fat away from the triceps muscle on the left arm and measuring the thickness (Fig. 5-3). Skinfold measurements can be located on the graph in Figure 5-4 and a patient’s percentile for body fat can be estimated. Other methods for determining body fat include underwater weighing (in submersion tanks), bioelectrical impedance, potassium-40 counting, and dual photon absorptiometry.

FIGURE 5-4 Triceps skinfold thickness and body fat composition. Figures from

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Weinsier and Butterworth. Handbook of Clinical Nutrition. The University of Alabama Department of Nutrition Sciences. (1981)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

|