Gallbladder

Charles Berk MD

The problems of the gallbladder related to gallstones present along a broad clinical spectrum. Most patients with gallstones remain clinically silent. Symptoms in many patients are mild and may be evaluated and treated in the outpatient setting and on an elective basis. However, gallstones can cause a variety of complications requiring hospitalization and rapid intervention. Previously, surgical removal of gallstones and the gallbladder from symptomatic patients was the only viable treatment option for most patients. However, now there are medical and endoscopic options aimed only at the treatment of the stones themselves that may be appropriate for selected patients. Further, laparoscopic cholecystectomy has largely replaced open cholecystectomy as the surgical procedure of choice for patients with gallstones. Appropriate management, especially with emergencies, requires a multidisciplinary team.

ANATOMY, PHYSIOLOGY, AND PATHOLOGY

The anatomy of the gallbladder is described in Chapter 24. Biliary pain results from impaction of the cystic duct by a gallstone, causing distention of the gallbladder (Giurgiu & Roslyn, 1996). In acute cholecystitis, occlusion of the cystic duct is accompanied by inflammation of the gallbladder. Bacteria can sometimes be cultured from the bile of patients with acute cholecystitis, but this is currently thought to represent an incidental and not a causal relation (Somberg et al, 1993).

Choledocholithiasis is associated with stones obstructing the common duct. Cholangitis is an infectious complication related to bile duct obstruction. The increased intraluminal pressure results in the reflux of bacteria into the hepatic veins and through the lymphatics into the systemic circulation. The commonly cultured organisms in cholangitis are Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, Pseudomonas, enterococci, and Proteus. Anaerobes are found in approximately 15% of infections, but these are usually present simultaneously with aerobic species. Common anaerobic bacterial infections in cholangitis are Bacteroides fragilis and Clostridium perfringens (Giurgiu & Roslyn, 1996; Somberg et al, 1993).

Gallstone Formation

There are three types of gallstones: cholesterol stones and two types of pigmented stones, brown and black. In the developed world, 70% to 80% of stones are the pure cholesterol type, or mixed cholesterol with calcium (Goldschmid & Brady, 1993). Brown stones are more common in developing countries. They develop as a result of parasitic infections leading to biliary stasis and secondary chronic anaerobic infection. Brown stones usually form in the intrahepatic bile duct rather than the gallbladder (Carey, 1993). Black stones form in sterile bile and are associated with conditions producing chronic hemolysis, such as sickle cell disease.

CHOLESTEROL GALLSTONES

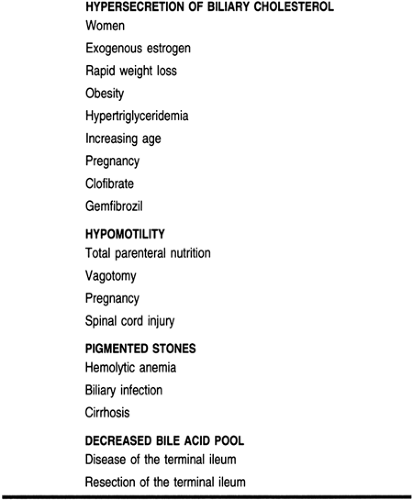

There are three contributory factors identified in the current model of cholesterol stone formation: supersaturation of the bile with cholesterol, accelerated nucleation, and gallbladder hypomotility. All three of these factors must be present for the formation of gallstones to occur, although each factor may predominate under different clinical circumstances.

Cholesterol is itself insoluble in aqueous solutions such as bile. However, with the addition of bile salts and lecithin, the three components come together to produce a soluble structure known as a micelle. Either hypersecretion of cholesterol or insufficient quantities of bile salts can result in a situation where the ability of cholesterol to be held in suspension in the bile is exceeded. Supersaturated bile is considered to be lithogenic. Increased cholesterol secretion is much more commonly implicated in stone formation, but decreased bile salts have been found as a risk factor in some indigenous populations in the American Southwest (Johnston & Kaplan, 1993).

Nucleation is the second step in stone formation. Studies done comparing the bile from patients with stones to patients without stones have shown that for any given concentration of cholesterol, crystal formation occurs more readily in patients with gallstones. Initially the cholesterol crystals are small and trapped in a mucin gel. This thick substance is referred to as biliary sludge and has been associated with pancreatitis. The mucoproteins in sludge are thought to be at least one of the pronucleating factors contributing to gallstone formation. The cholesterol microcrystals coalesce and grow into gallstones (Johnston & Kaplan, 1993).

Gallbladder stasis contributes to gallstone formation by interfering with the process by which sludge and microscopic crystals would normally be emptied from the gallbladder and by promoting prolonged contact between bile and pronucleating factors (Johnston & Kaplan, 1993; O’Donnell & Fairclough, 1993). Hypomotility is a prominent risk factor in pregnant patients, patients receiving total parenteral nutrition, patients with diabetes mellitus, and patients with spinal cord injuries.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

In the United States the incidence of gallstones is approximately 10% to 15% of the adult population (NIH, 1983). The incidence is greater in women, but increases in both men and women with age. Women and men in their 70s have an incidence of 40% to 50% and 16%, respectively. Past the age of 90, the incidence increases to over 80% among men and women (Watkins et al, 1993).

The development of symptomatic gallstone disease occurs at the rate of 1% to 4% a year in persons with gallstones (Gracie & Ransohoff, 1982). In 1991 about 600,000 cholecystectomies were performed in the United States. Gallstone disease is the most common cause of hospitalization for digestive disorders (Bowen, 1993; Ghiloni, 1993). Table 22-1 lists risk factors for gallstones.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

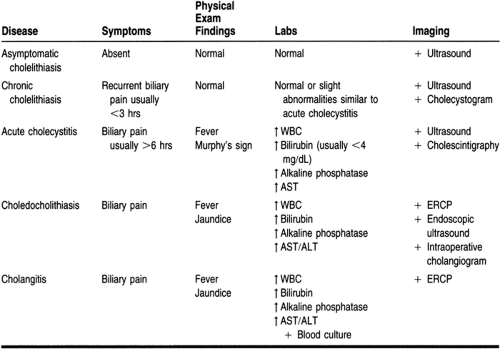

Most cases of cholelithiasis are asymptomatic, and most patients will not proceed to the development of symptoms. Once patients develop clinical stone-related disease, the hallmark complaint is abdominal pain. The characteristics, however, are nonspecific, and biliary pain has a broad differential diagnosis, including gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, reflux esophagitis, pancreatitis, renal disease, diverticulitis, radicular pain, and angina (Giurgiu & Roslyn, 1996; Moscati, 1996). Because asymptomatic gallstones are common, the identification of stones in the gallbladder should not preclude a complete evaluation of patients whose symptoms suggest other diagnoses.

Biliary pain has previously been referred to as biliary colic, but most authors agree that the term colic, which implies a spasmodic type of pain, does not accurately describe the pain of patients with gallstones. The pain of cholecystitis usually comes on suddenly and builds to a plateau quickly. It lasts several hours, with gradual resolution (Ghiloni, 1993). Uncomplicated biliary pain usually lasts less than 3 hours but may last as long as 24 hours. An episode of pain lasting more than 6 hours is suggestive of acute cholecystitis rather than chronic cholecystitis (Moscati, 1996; Somberg et al, 1993). The most common location for biliary pain is the epigastrium. The right costal margin is actually the second most likely location in which patients describe their pain (Doran, 1967). Patients may have pain that is localized or that radiates to the right scapula

and shoulder. Atypical symptoms such as fullness, bloating, belching, heartburn, and early satiety are extremely common, especially in the elderly (Watkins et al, 1993). Restlessness, nausea, vomiting, diaphoresis, and low-grade fever are findings frequently associated with biliary pain. The older teaching that pain is precipitated by the ingestion of foods and especially fats is mistaken. Many patients have no such association, and many patients have their symptoms at night (Moscati, 1996).

and shoulder. Atypical symptoms such as fullness, bloating, belching, heartburn, and early satiety are extremely common, especially in the elderly (Watkins et al, 1993). Restlessness, nausea, vomiting, diaphoresis, and low-grade fever are findings frequently associated with biliary pain. The older teaching that pain is precipitated by the ingestion of foods and especially fats is mistaken. Many patients have no such association, and many patients have their symptoms at night (Moscati, 1996).

Patients with chronic cholecystitis, characterized by recurrent bouts of biliary pain, usually have no fever, no abdominal tenderness, and no jaundice. Once patients begin to have symptoms from chronic cholecystitis, the episodes tend to recur with increasing frequency and severity. They usually have no fever, no abdominal tenderness, and no jaundice and have normal laboratory evaluations for white blood cell counts and bilirubin, liver enzyme, and alkaline phosphatase levels.

Patients with acute cholecystitis usually have biliary pain and may have fever. About 20% present with jaundice. Abdominal tenderness is common and a positive Murphy’s sign (eliciting pain when palpating the right upper quadrant as the patient takes a deep inspiration) is a classic finding. The white blood cell count is usually elevated, but to less than 15,000/mm3. The serum bilirubin value may be elevated but is usually less than 4 mg/dL. Transaminase and alkaline phosphatase levels may also be elevated (Ghiloni, 1993; Somberg et al, 1993).

Choledocholithiasis and cholangitis are difficult to distinguish from each other on clinical grounds. Choledocholithiasis is caused by the presence of a gallstone in the common duct. Cholangitis is an infection of an obstructed bile duct and is usually found in association with choledocholithiasis. Both sets of patients may present with abdominal pain, jaundice, and fever. This combination of symptoms is known as Charcot’s triad and is generally associated with cholangitis, but the same description may apply to patients with choledocholithiasis (Somberg et al, 1993).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree