Peripheral Vascular Disease

Eileen M. Reilly MS, RN, CS, FNP

Alice M. Arden MA, RN, CS, ANP

Harry L. Bush Jr. MD

Peripheral vascular disease is a term used to describe a variety of disorders that affect the structure and function of the arterial, venous, and lymphatic systems. This chapter will discuss these disorders with regard to their clinical presentation, diagnostic criteria, and treatment options. It will also provide recommendations for patient education.

ARTERIAL INSUFFICIENCY

Arterial insufficiency is a progressively debilitating disease process caused by atherosclerotic plaque narrowing the lumen of the medium and long arteries. The innermost layer of the artery wall, the intima consists of endothelial cells that regulate the entry of substances from the blood into the artery wall. Atherosclerosis is a degenerative disease characterized by elevated plaques known as atheromas found within the intima. Atheromas narrow the vessels, resulting in stenosis or occlusion of the artery. Atherosclerosis impairs the ability of the endothelium to prevent platelet aggregation and cholesterol build-up. The distal vessels of the lower extremities are often the target for atherosclerotic plaque, usually found at the arterial branches in the regions of the intima. Patients with diabetes mellitus have an accelerated rate of atherosclerosis occurring at a relatively earlier age. Therefore, persons with diabetes have a greater risk for compromised circulation and the development of arterial ulcers (Auth, 1997).

Atherosclerosis is the leading cause of death in persons 65 years of age or older. It is suggested that more than 2 million people in the United States have arterial disease. Atherosclerosis in the arteries of the lower extremities is a strong indicator of atherosclerosis elsewhere in the body. Signs and symptoms of arterial insufficiency commonly develop in people between the ages of 50 and 70 (Saunders, 1997). Intermittent claudication is a common clinical condition that is estimated to affect at least 10% of the people over 70 years of age (Santilli et al, 1996).

The most common manifestation of lower extremity atherosclerosis is intermittent claudication (Olin, 1993). “Claudication” comes from the Latin word claudicatio, meaning “to limp” (Santilli et al, 1996). Intermittent claudication is a pain in the leg that is brought on by walking and relieved by rest. This pain, characteristic of peripheral arterial occlusion, results from diminished blood flow and the inability of the collateral circulation to meet the oxygen demand of the exercising muscles. Pain also occurs because the flow of blood is insufficient to remove metabolic wastes such as lactic acid, a byproduct of anaerobic metabolism. Development of this occlusive symptom indicates that the diameter of the affected vessel has been reduced by about 50% (Dumas, 1995). Pain often presents in the calf, thigh, or gluteal area (Auth, 1997).

Claudication develops in a muscle distal to the complete or partial obstruction of a main artery. Localization of symptoms depends on the anatomic pattern of the arterial occlusive disease. Pain is often felt in the muscle group below the level of the arterial obstruction. Aortoiliac occlusive disease may cause buttock and thigh claudication. This syndrome, known as Leriche’s syndrome, causes atrophy and slow wound healing in the legs as well as an inability to maintain an erection. Iliofemoral occlusive disease results in thigh and calf claudication, and femoropopliteal occlusive disease results in calf claudication.

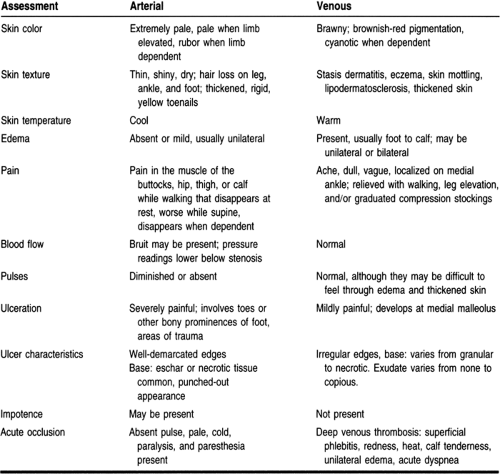

The most common site of peripheral arterial disease in both diabetic and nondiabetic patients is the superficial femoral artery. The second most common site is the aortoiliac segment. Tibial vessel disease, if present, may lead to critical ischemia of the leg, which is manifested by rest pain, nonhealing wounds, and gangrene (Santilli et al, 1996). Diseases affecting these vessels are more common in diabetic than nondiabetic patients (Krikorian & Vacek, 1995). Table 13-1 compares arterial and venous insufficiency.

A thorough patient history and physical assessment can help to distinguish ischemic ulcers caused by arterial disease from other types of ulcers (eg, venous, pressure, trauma, and vasculitis). The key to the diagnosis of arterial occlusive disease is the patient history (Auth, 1997). In taking the history, one must inquire about the onset and duration of symptoms and whether the leg pain is brought on by exercise and ceases with rest. How far can the patient walk before developing cramping pain? Which muscle groups are involved (calf, thigh, hips, buttock) (Uphold & Graham, 1994)? Does dangling the legs over the side of the bed relieve the pain? (This uses gravity to enhance circulation.) Males should be asked if impotence is present. Also, the provider should inquire about the patient’s medical history of atherosclerosis, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension. A family history of arterial insufficiency should be elicited as well. The patient’s social history (eg, smoking, sedentary lifestyle, and nutritional status) and a list of medications the patient is taking should be obtained.

The physical examination involves inspecting the patient’s body for changes in appearance. Hair growth may be absent over the affected area. The nails may appear thick, yellow, and brittle. Motor function of the affected part may be impaired or absent. The muscles may also appear atrophied from severe nerve and skeletal muscle ischemia. Patients often complain of numbness and tingling in the extremity, as well as an inability to distinguish touch from pressure, pain, and temperature change.

The skin texture may also change with arterial insufficiency. The skin may appear shiny, taut and thin, or scaly and dry

from ischemia, or progress to a deep red when the feet are in a dependent position. To assess the degree of arterial insufficiency, a reactive hyperemia test may be performed. This involves raising the legs above the level of the heart for 5 minutes until the legs become a cadaveric pale color, followed by lowering the legs to a vertical position. If the leg remains red for longer than 15 seconds, the circulation is severely compromised.

from ischemia, or progress to a deep red when the feet are in a dependent position. To assess the degree of arterial insufficiency, a reactive hyperemia test may be performed. This involves raising the legs above the level of the heart for 5 minutes until the legs become a cadaveric pale color, followed by lowering the legs to a vertical position. If the leg remains red for longer than 15 seconds, the circulation is severely compromised.

The skin temperature may vary. It is usually cool from vascular occlusion or vasoconstriction, hindering the blood supply. The best way to assess the temperature is to palpate the extremity with the dorsum of the hand.

Breakdown of the skin may occur with severe ischemia, resulting in ulceration. These ulcers are often found over pressure points such as the heels, toes, bony prominences, the dorsum of the foot, or the metatarsal heads. Ulcers, which cause severe pain, are often symmetrical and without drainage. Mild edema may also be present. Patients experiencing pain at rest may have edema because they keep their legs in a dependent position for pain relief.

Palpating the patient’s pulses provides information about the condition of the arteries. With arterial obstruction, the pulses may be absent or weak. Pulses should be assessed bilaterally for equality and strength using a Doppler stethoscope, if necessary. The physical examination should also include auscultation and evaluation of the blood flow. Normally, no sound is heard over a vessel that is patent. When blood flow becomes turbulent through an obstructed vessel, a blowing sound, or bruit, can be heard. Although the presence of a bruit is not always hemodynamically significant, it often indicates the start of chronic arterial occlusive disease long before symptoms such as cramps and pain appear (Bright & Georgi, 1992).

It is important in this patient population to check pulses in all regions of the body where major vessels are located, including the carotid, abdominal aorta, iliac, femoral, popliteal, posterior tibial, and dorsalis pedis. The clinical syndrome most difficult to distinguish from claudication is neurogenic claudication, more typically known as spinal stenosis. The pain characteristic of spinal stenosis is caused by a localized narrowing of the spinal canal caused by a structural abnormality that results in cauda equina compression. With spinal stenosis, the patient usually complains of pain in the lower back or buttock region as well as numbness and tingling in the feet with walking (Seller, 1996). Differentiation of claudication and spinal stenosis can be determined by the patient’s response to exercise. Symptoms of intermittent claudication are brought on by exercise and relieved with rest. Onset at a given distance of walking can be predicted fairly accurately. Spinal stenosis may also be precipitated by walking, but the distance walked before symptoms appear will vary. Standing may cause discomfort in patients with spinal stenosis, whereas intermittent claudication relieves it (Emergency Medicine, July 1993).

Nocturnal muscle cramps may be another symptom that can mimic claudication. However, these cramps are a common

complaint and have a tendency to occur in older persons. The cramps are not related to exercise. Tightness and pain in the calf after exercise can affect athletes with chronic compartment syndrome. This syndrome is usually found in young persons and presents after vigorous exercise and does not quickly subside with rest. Osteoarthritis of the hip may mimic thigh and buttock claudication. However, osteoarthritic pain occurs with variable amounts of exercise. It is relieved after long periods of rest and changes in severity from day to day (Santilli et al, 1996).

complaint and have a tendency to occur in older persons. The cramps are not related to exercise. Tightness and pain in the calf after exercise can affect athletes with chronic compartment syndrome. This syndrome is usually found in young persons and presents after vigorous exercise and does not quickly subside with rest. Osteoarthritis of the hip may mimic thigh and buttock claudication. However, osteoarthritic pain occurs with variable amounts of exercise. It is relieved after long periods of rest and changes in severity from day to day (Santilli et al, 1996).

Acute arterial occlusion differs from intermittent claudication in terms of the presentation of pain. Claudication is a progressively debilitating symptom more chronic in nature. Acute arterial occlusion is abrupt in onset and is more severe. This excruciating, unrelenting pain may occur suddenly, and neither rest nor activity relieves it. With acute arterial occlusion, the progressive signs of arterial insufficiency (eg, dry skin, brittle nails, and hair loss) may not be present. Often the foot is white and cold (Bright & Georgi, 1992). The patient may experience muscle weakness, possible paralysis, and paresthesia. Because of the cessation of blood flow to the extremity, there will be loss of pulses distal to the occlusion (Saunders, 1997). This situation warrants immediate referral to a vascular surgeon.

Another differential diagnosis that can be included is Raynaud’s disease. In Raynaud’s disease, episodic vasospasm produces closure of the small arteries in the distal extremities. This may be elicited by exposure to cold, vibration, or emotional stimuli (Saunders, 1997). Refer to Chapter, where this is discussed in greater detail.

Intermittent claudication can be chronic in nature but may become more incapacitating. The body attempts to compensate for this ischemic state by developing collateral circulation. The collateral circulation may not be sufficient when oxygen demand exceeds supply. The patient may notice a decrease in endurance and tolerance with exercise, resulting in a decrease in the distance and amount of walking. The pain may begin to occur at night. This pain is often relieved by dangling the foot off the side of the bed. When arterial insufficiency has progressed to such a level that the pain is constant and severe, patients may be unable to function. At this point arterial ulcers may appear in conjunction with limb-threatening ischemia and ensuing gangrene, necessitating amputation (Bright & Georgi, 1992).

The diagnosis of peripheral vascular disease is based on patient history, physical examination, and noninvasive testing. A variety of diagnostic tests are used to diagnose vascular insufficiency. Doppler segmental pressures with an ankle/brachial index (ABI) provide information regarding the extent of the disease. Doppler segmental pressures are obtained by placing appropriately sized blood-pressure cuffs around the arm and at the proximal thigh, the distal thigh, the proximal calf, and the ankle of the affected leg. Normal values for Doppler segmental pressures show an increase of greater than 20 mmHg from the brachial artery to the proximal femoral artery. An increase of less than 20 mmHg signifies significant aortoiliac occlusive disease. A blood-pressure drop of more than 30 mmHg between any two successive blood-pressure cuffs in the leg signifies a significant arterial obstruction. The ABI is a ratio of the ankle blood pressure to the brachial blood pressure. An ABI of greater than 0.85 is considered normal, an ABI of 0.50 to 0.84 suggests arterial obstruction with claudication, and an ABI of less than 0.50 suggests significant arterial obstruction with critical ischemia (nonhealing wounds or rest pain). The sensitivity and specificity of Doppler segmental pressures and ABIs are in the range of 70% to 85%.

Occasionally, patients have normal ABIs and segmental pressures at rest, but their symptoms strongly suggest claudication. In these patients, segmental pressures and ABIs should be obtained before and after exercise. For this diagnostic test, the patient may walk or lift the heels repeatedly to elicit a pain response. Exercise may reveal the arterial obstruction, resulting in a significant change in the Doppler segmental pressures and the ABIs found at rest.

An angiogram is indicated after evaluation of Doppler segmental pressures and ABIs if a patient with claudication is to undergo surgical or endovascular treatment. Angiography helps to reveal the exact location of the arterial obstruction and provides a road map for operative reconstruction. Because of the low but significant risk of renal failure, hematoma formation, or arterial injury, angiography should be performed only in patients who are considering surgery (Santilli et al, 1996).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a noninvasive, nonionic technique that produces cross-sectional images of the human anatomy through exposure to magnetic energy sources, without the use of radiation (Fischbach, 1996). MRI angiography provides both anatomic and hemodynamic information and is becoming a more common procedure to evaluate known vascular lesions. It may replace the gold standard of angiography, which requires the use of dye and the possible risk of renal failure.

There are several approaches to managing arterial insufficiency, beginning with risk factor modification. The single most important therapeutic intervention is smoking cessation. Hyperlipidemia should be controlled with dietary changes and if needed pharmacologic intervention. Dietary goals include a reduction of saturated fat intake and a reduction of cholesterol levels. For patients with diabetes, excellent glycemic control should be stressed. Blood pressure should be monitored and adequately controlled through mechanisms such as dietary changes, weight reduction, limitation of salt intake, stress reduction techniques, and pharmacologic management as needed. The patient should begin an exercise program that includes an aggressive walking program for approximately 30 minutes a day at a pace that elicits claudication. When claudication occurs, the patient should be instructed to walk a little further, stop, wait for the discomfort to pass, and then continue walking. A successful walking program can increase the distance to onset of claudication and help to develop collateral circulation (Olin, 1993).

Drug therapy for claudication enhances metabolic activity and increases blood flow to the affected muscles. Vasodilating agents have had little effect on patients with claudication. Antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants were thought to play a role in the treatment of claudication, but no data have been obtained to support their use in this condition. However, because of the high incidence of associated comorbidities in patients with claudication, consideration should be given to placing these patients on daily aspirin therapy.

Agents that decrease blood viscosity help promote blood flow to the extremities in patients with claudication. Pentoxifylline, a xanthine derivative, alters the structure of the red blood cell, decreases plasma viscosity, and decreases platelet aggregation

to enhance blood flow through the obstructed artery. Studies on the efficacy of pentoxifylline for claudication have produced conflicting results. This agent is the only medication approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of claudication. Pentoxifylline is given in a dose of 400 mg three times a day. Patients are usually given the drug for 1 to 3 months. If there is no change in the claudication after this time, the drug is discontinued. If the symptoms decrease, pentoxifylline therapy is continued. Reported symptomatic improvement rates vary from 10% to 20%. Five percent to 10% of patients cannot tolerate this drug because of gastrointestinal discomfort (Santilli et al, 1996).

to enhance blood flow through the obstructed artery. Studies on the efficacy of pentoxifylline for claudication have produced conflicting results. This agent is the only medication approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of claudication. Pentoxifylline is given in a dose of 400 mg three times a day. Patients are usually given the drug for 1 to 3 months. If there is no change in the claudication after this time, the drug is discontinued. If the symptoms decrease, pentoxifylline therapy is continued. Reported symptomatic improvement rates vary from 10% to 20%. Five percent to 10% of patients cannot tolerate this drug because of gastrointestinal discomfort (Santilli et al, 1996).

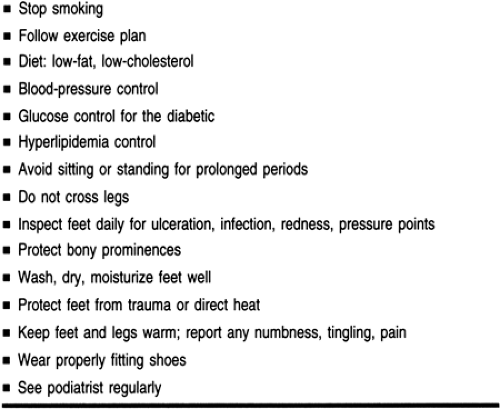

Most patients with claudication respond to conservative therapy. Local infusion of a thrombolytic agent may be the next option before resorting to surgical revascularization in cases of acute limb-threatening ischemia (Elson, 1994). Before a decision is made to perform an invasive procedure, the risk of limb loss and the overall cardiovascular risk to the patient must be considered. Invasive procedures should be performed on patients who have failed to respond to optimal medical therapy such as risk factor modification, a progressive exercise program, and pharmacotherapy. These procedures should also be performed on patients who have symptoms so severe that they interfere with the quality of life, or on patients with progressive arterial occlusive disease with the manifestation of limb-threatening ischemia (pain at rest, nonhealing wounds, gangrene) (Santilli et al, 1996). Refer to Table 13-2 for patient teaching guidelines.

BUERGER’S DISEASE

Thromboangiitis obliterans, more commonly referred to as Buerger’s disease, is a recurring inflammatory process affecting the small and medium-sized arteries and veins of the extremities. Buerger’s disease is more commonly found in males than females between 35 and 50 years old. Risk factors include cigarette smoking and a family history. The cause is unknown.

Patients most often present with pain in either the feet or hands while at rest, numbness, and tingling, as well as color and temperature changes. If any trauma to the affected extremity is experienced, ulceration may develop. Superficial thrombophlebitis manifested as erythema, warmth, and swelling often precipitates arterial signs and symptoms. Patients who develop ulceration are at great risk for infection, leading to possible amputation. Pulses in the extremities are either diminished or absent, and swelling is often noted in the feet. Angiography is indicated.

Patents should be taught to protect the extremities from trauma. Their hands and feet should be kept clean, dry, and moisturized. Patients may also promote circulation through exercise, such as the Buerger-Allen exercises. They should stop smoking. Pain can be controlled with analgesia or alternative therapies.

ANEURYSMS

An aneurysm is a defect in the anatomy of an artery resulting in weakness, stretching, and ballooning out of the arterial wall. The most commonly affected artery is the aorta; in 80% of cases the abdominal region is involved. There are three types of aneurysms: fusiform, saccular, and dissecting. Fusiform involves the ballooning of the entire circumference of the artery. Saccular involves only one side of the artery ballooning. A dissection occurs from a tear in the intima of the vessel, allowing blood to accumulate between the layers. A pseudoaneurysm is an accumulation of clot which forms outside an artery; it often occurs after trauma or an invasive procedure.

Aneurysms are more common in the population over 50 years of age, affecting men twice as often as women. Risk factors associated with aneurysmal dissection are hypertension, hyperlipidemia, atherosclerosis, smoking, diabetes, and a family history of aneurysm.

Most often aneurysms are asymptomatic and are discovered incidentally during ultrasound, computed tomographic (CT) scanning, or MRI. However, if a patient complains of symptoms such as chest, flank, or back pain, with any of the associated risk factors, an abdominal examination focusing on palpation and auscultation of the aorta should be performed. If suspicion of aortic aneurysmal disease arises, the patient should be referred to a vascular surgeon for consultation.

Aneurysms are diagnosed by ultrasound, CT scan, or MRI. Treatment, either surgical or monitoring every 4 to 6 months by imaging, should be implemented, along with risk factor modification. The primary care provider should also evaluate these patients for aneurysmal disease elsewhere in the body.

TEMPORAL ARTERITIS

Temporal arteritis, also known as giant cell arteritis, is a systemic condition characterized by chronic inflammatory changes of the aorta and its major branches. It occurs most commonly in Caucasian women over the age of 55. The onset of symptoms may be abrupt or insidious. The patient may present with headaches, often unilateral, and pain in both the pelvic and shoulder girdles (polymyalgia rheumatica). Visual disturbances, a particularly devastating complication of temporal arteritis, can also occur (Dean et al, 1995). Some atypical presentations include fever of unknown origin and weight loss.

On examination, the patient may have localized temporal artery tenderness, redness, decreased pulsation, induration, or

in extreme cases scalp necrosis. Temporal arteries are normal in one third of the population. The patient may have ophthalmologic findings such as ophthalmoplegia and visual loss. On funduscopic examination, the patient may have pallor and swelling of the optic discs, an early sign of temporal arteritis; in the later stage of this disease, optic atrophy may exist. Systemic manifestations usually result from ischemia of affected arteries or inflammation. Bruits may be heard in the head and neck. The pulses in the upper extremities may be absent. Neurologic deficits, memory loss, delirium, dementia, or transient ischemic attacks may appear should this condition worsen.

in extreme cases scalp necrosis. Temporal arteries are normal in one third of the population. The patient may have ophthalmologic findings such as ophthalmoplegia and visual loss. On funduscopic examination, the patient may have pallor and swelling of the optic discs, an early sign of temporal arteritis; in the later stage of this disease, optic atrophy may exist. Systemic manifestations usually result from ischemia of affected arteries or inflammation. Bruits may be heard in the head and neck. The pulses in the upper extremities may be absent. Neurologic deficits, memory loss, delirium, dementia, or transient ischemic attacks may appear should this condition worsen.

If temporal arteritis is suspected, a temporal artery biopsy should be performed. However, a negative biopsy does not always rule out temporal arteritis. An erythrocyte sedimentation rate should be obtained; in temporal arteritis, it is almost always 50 mm/hour or more.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree