Health Promotion and Disease Prevention

Robert V. DiGregorio Pharm D, RPh

Joanne K. Singleton PhD, RN, CS, FNP

Health promotion and disease prevention have often been overshadowed by the efforts of the practitioner to restore health and manage disease states. Primary care providers recognize that the old adage “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure” is not only a truism, but imparts significant health, as well as, financial benefits. For example, smoking cessation programs, which may prevent a variety of diseases, could eliminate many of the more than 400,000 deaths and reduce the associated health care costs of more than $65 billion per year in the U.S. Health promotion, however, is often confused with traditional preventive medicine which has focused on disease prevention and has not fully integrated the concept of overall wellness. While health promotion is about disease prevention, it goes much further. This chapter will discuss health promotion from the perspective of relationship-centered care, including screening for early indicators of disease and advocating for overall wellness.

HEALTH PROMOTION IN RELATIONSHIP-CENTERED CARE

The expanded definition of health promotion includes areas of wellness such as injury prevention, healthy eating and reducing stress, to name a few. The concept of overall wellness and health promotion can be easily coupled to the concept of relationship-centered care when viewed as a process of empowerment. Health promotion is a process that enables individuals to improve their quality of life through a partnership with their families and health care providers who assist the individual in making informed decisions about their health. Once the decisions are made by the individual patient and their family, the health care provider moves into a position that provides support for and encourages participation in the individual’s plan for healthy living. Described in this chapter are various aspects of health promotion that could be considered in health-promotion or wellness plans that providers develop with their patients.

The concept of relationship-centered health promotion is echoed in the current national health and wellness initiative, Healthy People 2000 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [DHHS], 1992) and the Guide to Clinical Preventive Services (U.S. Preventive Services Task Force [USPSTF], 1996). The central purpose of Healthy People 2000 was to increase the proportion of Americans who live long and healthy lives by maintaining a full range of functional capacity throughout their life. The lifestyle promoted in this initiative enables an individual to enter into satisfying relationships with others, pursue career goals, and enjoy recreational activities. The impetus to accomplish these goals and modify behaviors comes from the increasingly health-conscious, responsible public in partnership with their health-care providers. Other goals of Healthy People 2000 included reducing health disparities among Americans and achieving access to preventive services for all Americans. It is interesting, and disappointing, to note that as the year 2000 approaches, the three primary goals of Healthy People 2000 have not been fully met. These ambitions must therefore continue into the 21st century.

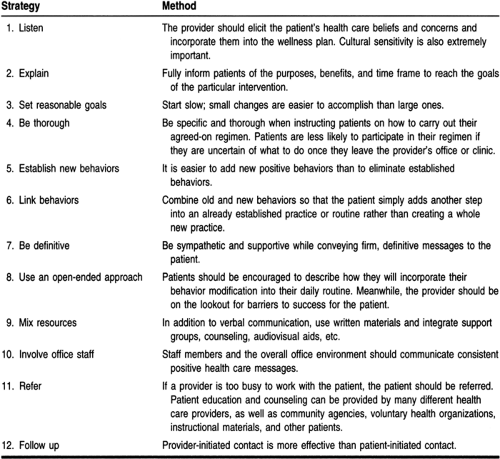

The Guide to Clinical Preventive Services reflects relationship centered care. It provides through detailed guidelines for health care providers in their role as counselors, health facilitators, and patient educators. Many patients read magazines and pamphlets pertaining to their health and are aware of the risks involved with certain behaviors. Despite their knowledge, they continue to partake in a variety of risky behaviors. Information and knowledge are important for promoting a healthy lifestyle: patients need to motivate themselves and rely more on an overall strategy for changing less-than-optimal health behaviors. Strategies for changing health behaviors can be incorporated into routine health visits, and are outlined in Table 3-1.

Implementing patient counseling in the practice setting raises important issues for providers. Issues regarding the value of screening and the appropriate time to screen patients are discussed below and in the individual chapters in Part 2. Other issues may arise as barriers to implementing counseling interventions, such as insufficient reimbursement, patient volume requirements, provider uncertainty about how to counsel effectively, varying interest on the part of patient or staff, and lack of an organizational system of support to facilitate the delivery of patient education (USPSTF, 1996; MacLean, 1996). Many of these issues are addressed by the government publication “Put Prevention into Practice” (PPIP), the U.S. Public Health Service’s prevention implementation program (DHHS, 1994). PPIP and the strategies provided in this chapter can serve as tools to assist the provider in developing an ongoing dialogue to encourage patients at every visit to change their personal health practices.

EVIDENCE-BASED HEALTH SCREENING

Effectiveness should be the most basic requirement for providing any health care service. This includes health-promotion activities, where the health care provider has the ethical responsibility to “do no harm” to patients. Effectiveness is usually determined from compilations of data or evidence from large randomized clinical trials. The ability to track down, critically appraise and incorporate this evidence into clinical practice has been referred to as “evidence-based medicine.” Evidence of effectiveness alone, however, is not a sufficient reason to perform a particular screening. Factors other than effectiveness,

reflecting the trade-offs and broad implications of screening, are relevant to the goals of health promotion.

reflecting the trade-offs and broad implications of screening, are relevant to the goals of health promotion.

When deciding on a particular screening instrument, providers must decide to what degree the information from the screening procedure is accurate and reliable. The provider and patient must also determine how the data gained from the screening process will ultimately be applied to patient care. For example, obtaining mammographies in younger women is the subject of great controversy (Schmidt, 1995; Leitch, 1995). Mammographic screening, yielding false-positive findings, has caused many women to undergo breast biopsies that uncovered normal tissue. In retrospect, these biopsies were not only unnecessary, but also subjected the women to a painful, invasive procedure and the accompanying anxiety of a possible breast cancer diagnosis. If a younger woman understood this possibility prior to requesting or submitting to a mammogram, she might opt to wait and simply continue to conduct monthly breast self exams with annual clinical breast examinations. Considerable controversy also exists with regard to screening asymptomatic patients for colorectal cancer (Hart et al, 1995) and prostate cancer (Mandelson et al, 1995).

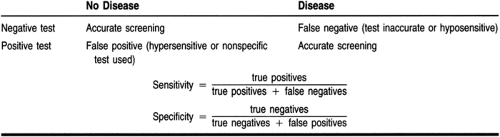

Misinterpretation of screening tests, based on false-positive and false-negative findings, may lead to over- or undertreating patients. While false-positive results may cause undue anxiety and diagnostic work-up for a patient, a false-negative finding can give a patient a false sense of security as well as delay treatment. Providers must understand the sensitivity, specificity, and reliability, underlying disease prevalence and relative cost of screening before incorporating a screening process into a patient’s wellness plan.

Sensitivity

The ability of a particular test to detect an abnormal condition is referred to as the sensitivity of the test. A test that detects minute variations from the normal condition would be described as a highly sensitive test. Even highly sensitive tests, however, do not always confirm specific disease states. For example, current technology allows for the measurement of gamma glutamyl transferase (GGT) levels within 1 unit/L; thus, a GGT level of 1 unit above normal could be detected. However, this elevated level does not differentiate between alcoholism, hepatitis, smoking, lupus, or a biliary obstruction. In fact, it may not indicate any abnormal condition. The smell of a patient’s clothing may, on the other hand, reveal the unmistakable odor of cigarette smoke. Of course, this rudimentary test would not reveal how much the person smokes or even if the smell was from the individual or second hand.

Specificity

Specificity refers to the ability of a test or screening procedure to identify the exact problem or condition. In the above example, GGT was a highly sensitive but nonspecific screening test. Examples of highly specific screening tests include: blood pressure measurement for hypertension, ejection fraction for cardiac

function, prostate-specific antigen for prostate cancer, and blood cultures for infectious pathogens. It is important to consider that a positive finding in a highly specific test does not necessarily confer a disease. The possibility of second-hand smoke in the above example illustrates this scenario. Another example of specificity without diagnostic merit would be the use of a blood level to determine drug toxicity. While an elevated level may certainly be specific to the drug product in question, not every patient with an elevated level will exhibit toxic effects. A summary of specificity and sensitivity measures is shown in Table 3-2.

function, prostate-specific antigen for prostate cancer, and blood cultures for infectious pathogens. It is important to consider that a positive finding in a highly specific test does not necessarily confer a disease. The possibility of second-hand smoke in the above example illustrates this scenario. Another example of specificity without diagnostic merit would be the use of a blood level to determine drug toxicity. While an elevated level may certainly be specific to the drug product in question, not every patient with an elevated level will exhibit toxic effects. A summary of specificity and sensitivity measures is shown in Table 3-2.

Reliability

Tests used in screening procedures may be highly sensitive and specific, yet remain unreliable. Reliability takes into account the accuracy and precision of the test. Test results may indicate a specific finding marginally above the norm, but because of technical error, expired reagents, or faulty test techniques, it may be inaccurate. Variability in the performance of the test procedure or examination can lead to unreliable results by compromising precision or reproducibility. Blood pressure readings taken incorrectly (eg, the arm is not at heart level), by inexperienced individuals, or the use of electronic blood pressure measuring devices may increase the amount of blood pressure screening and monitoring data available to providers; however, this data may be imprecise, inaccurate and therefore unsuitable for making health care decisions.

Cost Factors

In an ideal world of unlimited resources, patients would have infinite access to their health care providers, health technology, and health care products. However, resources are increasingly limited, and the utility of screening for conditions, simply because the technology exists, is not appropriate. Even screening that is relatively free may lengthen a health care visit and prevent another patient from obtaining care that day. Extremely specific, sensitive and reliable testing may be available but not utilized due to disproportionally high costs as compared to an older, less expensive test. Screening for cervical cancer with newer test methods rather than Pap smears is a good example of this phenomenon. For each screening test, the cost of evaluating all susceptible individuals must be weighed against the prevalence of the condition and the cost of treating the condition. In some cases, the relatively low prevalence and low cost of treating a disease may make implementing such a screening program unrealistic. Likewise, therapy leading to an individual’s complete cure of a disease may cost less than screening or immunizing an entire population.

SCREENING

As a form of health promotion and disease prevention, screening can be as simple as questioning a patient about the common warning signs or symptoms of a disease state, or as complex as subjecting the patient to invasive examinations or testing procedures. The most common areas of health screening include the prevention and early identification of coronary artery disease and a variety of cancers. The warning signs and symptoms and current approaches to this type of screening are covered in detail in the individual chapters of Part 2. Screening for high-risk behaviors, injury prevention, and complementary approaches to wellness are discussed in this chapter.

GROWTH AND AGING IN HEALTH PROMOTION

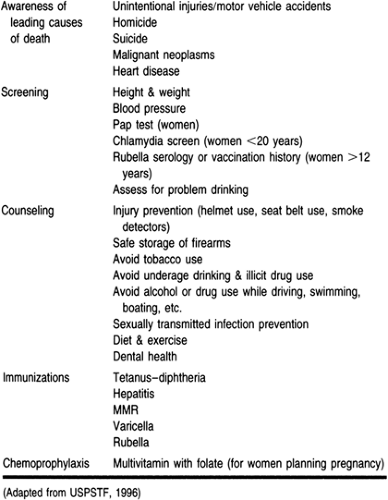

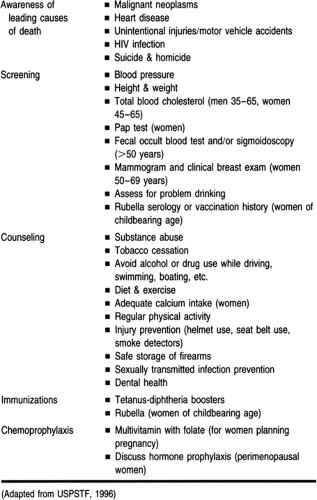

Primary care providers must use their time wisely to provide counseling on high-risk behaviors. It may be inappropriate to counsel certain age groups on certain behaviors. If morbidity and mortality data are considered, a provider might decide that counseling a 70-year-old female of a 45-year marriage on birth control and sexually transmitted diseases might not be prudent. Likewise, counseling the 20-year-old college student of the dangers of falls and this year’s influenza vaccine may be equally pointless. Realistic expectations for health promotion during routine health examinations are outlined by specific age groups in Tables 3-3 and 3-4.

Developing health-promotion and disease-prevention plans with patients requires consideration of growth, development, and maturation across the adult lifespan. Milestones of the young adult, middle adult, and older adult stages help to provide a framework for health-promotion and disease-prevention activities.

Young Adult

The young adult stage spans the ages of 18 to 35 years. The physical and emotional changes that occur during this time, and the style of learning, through experimentation and experience, focus health-promotion and disease-prevention activities. Generally, by the age of 20, physical growth is complete. This period

is often described as the healthiest time of life. Maintaining proper functioning is a goal for this period of time that will impact the person not only as a young adult, but throughout adult life. Toward this end, health-promotion and disease-prevention activities should be focused on developing healthy lifestyle behaviors, early detection of health problems, prevention of accidents, injuries, and, the morbidity and mortality associated with violence.

is often described as the healthiest time of life. Maintaining proper functioning is a goal for this period of time that will impact the person not only as a young adult, but throughout adult life. Toward this end, health-promotion and disease-prevention activities should be focused on developing healthy lifestyle behaviors, early detection of health problems, prevention of accidents, injuries, and, the morbidity and mortality associated with violence.

Middle Adult

Middle adulthood spans the ages of 35 to 65. This period of time is marked by biologic changes. It may also be a time of turmoil, reassessment, and change. Leading causes of death during this time are heart disease, lung cancer, cerebrovascular disease, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, and, obstructive lung disease. Genetics, as well as other factors that health promotion and disease prevention activities can be directed toward, such as nutrition and exercise, contribute to these conditions.

Older Adult

By the year 2030, it is projected that 18% of the population will be over age 65. Within the older adult age group is the fastest growing segment of the population, those over the age of 85. It is expected that by the year 2000 this group will have increased by 70% (U.S. Senate Special Committee on Aging, 1991). Physiologic aging is universal, progressive, decremental, and intrinsic (Goldman, 1986). Age-related changes are inevitable but occur with variability. Chronic illness and functional disabilities are interrelated and increase with age. Thirty-three percent of those over 65 years have some type of functional limitation related to a chronic condition (US Public Health Service, 1991).

Accidents are a common problem of the elderly. With physiologic aging come decreased sensory acuity, reaction time, muscle strength, and impaired balance. As a result, in those over 70 years of age, falls are the greatest cause of accidents, with 50% of the falls caused by environmental factors (U.S. Public Health Service, 1991). Risk factors for falls include: functional status and use of assistive devices, polypharmacy, and medical history. Providers should evaluate the fall potential of patients and develop strategies for fall prevention which may include minimizing environmental risks, teaching or reteaching adaptive behavior, and reducing accompanying risk factors such as changes in visual acuity.

The leading causes of death is this age group are heart disease, cancer, cerebrovascular accident, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pneumonia, influenza, and injury. Alcohol and drug abuse, homelessness, and physical abuse are also concerns

in the older adult population that must be considered in health-promotion and disease-prevention activities.

in the older adult population that must be considered in health-promotion and disease-prevention activities.

Health Care Decisions

When patients are in good health, matters related to their ability to make health care decisions are generally not of concern. It is, however, important for primary care providers to discuss with patients their right to direct the kind of health care they would or would not want, in the event that they are unable to do so.

Advance directives are broadly defined to include living wills and appointment of a health care agent. A living will is a document created by an individual to authorize in advance withholding or withdrawing artificial life-support measures in the case of terminal or debilitating illness, injury, or irreversible coma, it is signed, dated and witnessed. All but three states, Massachusetts, Michigan, and New York, have living will statutes.

Appointing a health care agent differs from state to state and may be referred to as: Durable Power of Attorney for Health Care; Health Care Power of Attorney; Appointment of a Health Care Agent; or, health care proxy. Regardless of state mandates, the objective of appointing a health care agent is the same: allowing an individual to appoint someone they trust to control their health care through the individual’s written instructions.

Competent adults have the right to create an advance directive regarding treatment decisions, including life-sustaining measures. There are state-mandated forms for advance directives that the patient completes. Patients have the right to change their health care agent, and/or change their written instructions, or cancel their advance directive, at will. If the patient has both a living will, and an appointed health care agent, usually the appointment of the health care agent takes precedence.

Discussing advance directives with patients is an important part of proactive primary care. Encouraging patients to appoint a health care proxy and knowing whom the patient has appointed are essential to respecting a patient’s wishes should they be unable to make their own health care decisions.

Adult Immunizations

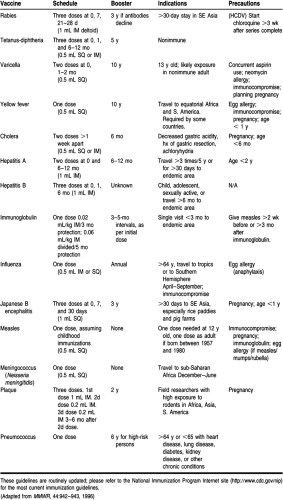

Most immunizations are completed during a person’s childhood health visits. For many individuals, the need for adult immunizations is limited to booster injections of tetanus (usually combined with diphtheria as Td) and measles vaccine (for adults born after 1956 without evidence of immunity or who attend high school or college). After age 65, influenza and pneumococcal inoculations are indicated as discussed in the following sections. Other conditions exist where adults may need to receive immunizations, including foreign travel or immigration to a foreign country, working in high-risk areas (including health-care workers), during periods of immunosuppression, and for missed childhood immunizations. A summary of the adult immunization guidelines can be found in Table 3-5. Travel guidelines are updated routinely. Before foreign travel, travelers should consult their primary care provider for the latest guidelines. Patients may also contact the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention directly or through the Internet to access these guidelines.

INFLUENZA

Each year in the United States, approximately 20,000 individuals die from influenza; 80% to 90% of these deaths are in persons aged 65 or older (Plichta, 1996). Influenza vaccines vary from year to year, therefore, immunization against influenza should be administered annually. Patients should receive the influenza vaccine beginning in September. Patients who receive their vaccination as late as December or January may still be protected. Patients who receive their vaccination during a flu outbreak should also receive antiviral prophylaxis with amantadine or rimantidine for 2 weeks.

PNEUMOCOCCAL DISEASE

Pneumococcal disease is the most common cause of hospitalization and death in persons age 65 years or older (Plichta, 1996). Pneumococcal vaccine has a varied effectiveness depending on the age and immunologic status of the patient, with patients under 55 years old deriving the most benefit (Plewa, 1990). Pneumococcal vaccine is given only once, but may be repeated for high-risk patients every 5 to 6 years.

TETANUS

Tetanus guidelines were established in the 1950s for childhood immunization. This decreased the incidence of tetanus among children and young adults. Older adults, however, have been shown to have nonprotective tetanus antibody titers in many cases (Alagappan et al, 1997). It is believed that this lack of protective titer may be caused by the failure to receive the initial tetanus vaccination or booster immunizations every 5 to 10 years. A cost-effective approach to tetanus vaccination in this population includes combining tetanus with diphtheria (Td)at least every 10 years for adult patients.

IDENTIFYING AND MODIFYING HIGH-RISK BEHAVIORS

High-risk behavior has been associated with a multitude of disease states and injuries. In many cases individuals are involved with multiple high-risk behaviors, such as smoking and drinking, driving while intoxicated (often without the protection of a seat belt). The possible combinations and permutations of high-risk behaviors is almost endless. In addition to the possibility of contracting disease or incurring injury, the injuries sustained while engaging in high-risk behaviors may be more severe, lead to longer hospitalizations and subsequently higher health care costs. In one study, total hospital costs were 7% higher for motorists not wearing seat belts and motorcyclists not wearing helmets than for their matched counterparts who used protective equipment (Mackersie et al, 1995).

High-risk sexual behavior, the use of alcohol, drugs and tobacco, and other injury-prone behavior was addressed in the national health promotion initiative, Healthy People 2000. Whether or not the public has significantly modified these behaviors and reduced morbidity and mortality has not yet been determined; however, at least one study of New Jersey college students determined that the national objectives for tobacco and cocaine use will be met. Unfortunately, the same study determined that the national targets set for condom and birth control use, alcohol and marijuana use, and seat belt and helmet use are not likely to be met (Lewis, 1996).

Smoking

Cigarette smoking has been linked to serious pulmonary, cardiovascular, and oncologic problems and remains the most important modifiable cause of premature mortality in the United States (MMWR, 1994; DHHS, 1996). It has been estimated that more than 420,000 Americans die each year (20% of all deaths) as a result of smoking (DHHS, 1996). In 1997, after cigarette manufacturers faced the public in a series of legal actions, major regulatory concessions were made and the tobacco industry agreed to spend $368 billion dollars, over the next 25 years to foster health promotion. While both the public and the tobacco industry have taken more responsibility for their actions and the associated health problems, approximately 25% of Americans, or 46 million, still smoke. While the percentage of Americans who smoke continues to decline, the nation’s goal of reducing smoking prevalence to no more than 15% of adults, and decreasing the number of new smokers, by the year 2000 will not be reached (USDHHS, 1992). Substantial efforts to help smokers quit must continue well into the new millennium.

As a smoker quits, the health care risks associated with smoking decline drastically. The risk of lung cancer drops by 50% after 10 years of abstinence, the risk of mouth and throat cancers drops by 50% in 5 years, the risk of a myocardial infarction is reduced by 50% in 1 year. After 10 to 15 years, many of the risks associated with smoking are reduced to the same frequency as nonsmokers. Effective counseling and therapy for the cessation of smoking may be the single most important health-promoting activity that health care providers undertake.

Guidelines for primary care providers on smoking cessation have been published (USDHHS, 1996). Counseling, support systems and pharmacotherapy are described in these guidelines. Keys to successful smoking cessation programs and newer pharmacotherapy, introduced after the guidelines were originally published, are summarized in Tables 3-6 and 3-7.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree