Family and Cultural Assessment Measures in Primary Care

Carol Green-Hernandez PhD, FNS, ANP/FNP-C

Primary care that is truly family-focused uses the family unit as a basis for data gathering in assessing and meeting patient needs. Successful implementation and evaluation of management interventions can occur when the patient is a partner in the entire primary care process. This chapter will illuminate the challenge to primary care of placing family and culture in context with demographics, geography, and economic influences. Models for family assessment, and for family-focused cultural assessment, will be presented as tools for data collection in primary care. This assessment data is foundational to the patient’s health history. As an antecedent to this content, values clarification will be discussed as a strategy that can help the provider in giving patient-centered care that is salient for both provider and patient.

VALUES CLARIFICATION IN PRIMARY CARE

The primary care provider may find that clarifying their own values and beliefs can assist in discerning possible sources for prejudicial assessment of patients. Values clarification may prove especially helpful when caring for patients whose values, beliefs, and health behaviors differ from those of the provider. After clarifying what is important for oneself, the provider can sift out values and beliefs that are congruent with those of their patient. Areas of value digression might be found between the patient and the provider. But the process of self-reflection in values clarification can help the provider to avoid out-and-out conflict with the patient when strong differences in beliefs emerge. Clearly, such conflict can jeopardize a therapeutic relationship, the purpose of which is to facilitate patient health rather than serving as a foundation for a “bully pulpit.” Values clarification can help the provider to deliver primary care unburdened by anger or betrayal if a patient chooses to ignore the health plan. A sample values clarification tool and directions for its use are found in Appendix 2-1.

Values clarification can empower provider and patient alike. The goal, of course, is to create and maintain primary care that is relationship-centered for provider and patient. Such care must be both legal and ethical, while promoting self-actualization of the patient and family (Green-Hernandez, 1997). This means that the provider is sensitive to both verbal and nonverbal cues and behaviors, including body stance, positioning, and use of eye contact. Similarly, maintenance of body space and use of touch can signal respect or its lack. Patients are not passive recipients of primary care—they are in fact active partners in that care. By using relationship-centered care as a basis for communicating and working with patients, the provider can avoid some of the value-laden problems that often emerge in the course of primary care that is provider-controlled. The patients’ feelings, values, and beliefs, including those pertaining to health, are integral to all care management strategies in primary care.

When values conflict between provider and patient and/or the family, referral to a different provider may need to be considered if consensus on treatment options cannot be reached. This is exemplified by a case where a provider advises adoption to a young unmarried woman who is unexpectedly pregnant, and who asks for abortion services. If the provider does not subscribe to reproductive choice, this value can impact a patient’s decision-making capability to the extent that she follows through on a pregnancy against her will. This scenario’s implications may not end there. Her family may pressure her to keep the baby, leading her to abandon plans to complete her education. Conversely, she may follow-through on adoption, but may later regret this decision. This scenario is one that is very real. Because there are no easy answers to many of the dilemmas faced in primary care, it is incumbent on the provider to examine personal values and beliefs before addressing patient care.

TAKING VALUES CLARIFICATION TO THE FAMILY

Like all open living systems, the family is an evolving entity. Today a family may be headed by an emancipated minor, a single parent, two or more unrelated individuals, same-sex heads-of-household, as well as the so-called “traditional,” nuclear family. The concept of a “typical” family eludes characterization. The family is what its members envision it to be, with the group defining membership as the key to family composition. This vision for family demography impacts family functioning. It is this impact, and the implications it holds for health promotion and illness management, that presents an important challenge to primary care providers.

FAMILY-CENTERED PRACTICE

Traditionally, the practice of primary care treated the patient as an individual who required treatment. The family was treated as an extension of the patient insofar as the individual’s illness might be communicated to other members. Some enlightened providers were also concerned about the impact of illness or treatment requirements on family members but, by and large, care delivery was individual- rather than family-focused. In Western medicine, this tradition was further underscored by

society’s cultural belief in the primacy of individual rights and freedoms.

society’s cultural belief in the primacy of individual rights and freedoms.

Today the practice of primary care is experiencing a realignment toward family-centered health care. This is a clear and important difference from specialty practice, whose emphasis is the individual. There are two paths toward family-centered practice, each with its own distinct, theoretical underpinnings. The first is a traditional path, which centers on individual-focused care. The second path uses a family systems framework. This path is seen as the most inclusive of individual and family members. It is based on respect for the primacy of the individual. The family systems path is seminal to primary care practice that is relationship-centered. The provider must keep in mind that confidentiality in dealing with an individual family member must be at the forefront of relationship-centered care. Family-centered practice does not imply abandoning the legal and ethical responsibilities the provider owes to the patient.

The Traditional Path in Primary Care

This first and earliest practice model sees the family as comprised of individuals. The outcome of care delivered within an individual-focused model uses family studies as well as developmental and social learning theory in organizing, explaining, and predicting care needs for that individual (Wright & Leahey, 1993). This model is exemplified by the anticipatory guidance given to the caretaking adult of the patient with dementia, or to the parent of a teenager at the time of her pre-college physical. The focus of concern is the patient or the family, rather than an integration of the patient and the family. The traditional path approaches patient management from the perspective of either the patient or the family, rather than focusing on the family as a whole.

The Family Systems Path in Primary Care

The second path for primary care is delivered within a family systems framework. The family systems path targets each individual family member as well as the family as a whole, at one and the same time (Wright & Leahey, 1993). The family systems path is optimum in a practice that is relationship-centered. What happens to the patient is seen as happening to the family as a unit. Primary care delivered to the individual impacts the family as well. Whether integrating health promotion or confronting illness management, family members experience together the provider’s professional caring for, communication with, and treatment of one of its members. This is the optimal model for the practice of relationship-centered primary care. This model is not seen as an evolutionary product of the first, individual-focused path but, rather, as an alternate route that can form a strong basis for humanistic primary care. The Family Systems framework guides how this care impacts family functioning from the perspective of each family member as an individual and as a member of a unique group. Family members’ feelings and responses to the patient’s health status and care management are recognized as important to the family’s inter-actional function. Care given to one member is evaluated within the context of other family members’ responses to and connectedness with the patient, while keeping in mind that the community is part of that connectedness. This kind of care delivery model is inherently more holistic than the traditional family practice model, in which care is individual-focused. Conversely, a Family Systems framework guides the provider in treating the patient as a being who is interconnected with others in the family and, in a broader way, with the community.

CLINICAL PEARLS

Care that is family-focused does not imply that all members are always entitled to know every aspect of each other’s primary care issues. The primary care provider must sometimes walk a fine line, balancing family support with individual privacy needs.

FAMILY SYSTEMS IN PRACTICE

The following three examples will introduce the idea of a Family Systems perspective for practicing primary care. Their presentation exemplifies the interconnectedness that emerges from giving primary care that uses Family Systems as a practice foundation.These three case presentations then will be placed within the context of family assessment.

Case # 1

A young woman is diagnosed with breast cancer. The provider works with her and her husband in deciding upon referral options for cancer treatment and community resources. This management of her primary care needs does not occur in isolation. The young woman’s church, neighbors, co-workers, and parents of her children’s friends all share in her family’s fear and anxiety. Many people come forward to volunteer their help in her and her family’s care. Many others in the community may forge new bonds in helping the family meet financial and family-management challenges associated with her cancer treatment.

Case # 2

A respected elderly man in the community is diagnosed with dementia of the Alzheimer’s type. The primary care provider is concerned with how this diagnosis impacts both the patient and the family’s functioning. The provider works with the wife and an adult son in developing a management plan. Because of the provider’s referral to the local home care or community-based organization, a plan of care is set up to develop and implement a respite network. Friends and neighbors have expressed an interest in helping the family with respite activities. Their contributions are included in the management plan. The outcome of this management plan is a coordination of efforts that support the patient’s primary care needs, while assisting his family in providing for round-the-clock care.

Case # 3

A recent flu epidemic ultimately takes the life of an 18-year-old patient with asthma. The provider practices primary care within a Family Systems perspective. This means that the provider’s work does not end with the teen’s death. In practicing relationship-centered primary care that is family-focused, the provider collaborates with other providers in assessing intervention needs of the victim’s family and close friends. This assessment can serve as a springboard for community involvement. In this instance, the following autumn the local high school’s PTA coordinates with local health authorities to set up a free influenza immunization clinic for the entire community. All of this is done in the teen’s memory.

THE FAMILY ASSESSMENT

Family assessment data can help the provider deliver individualized primary care. Such data can enhance the provider’s understanding of the family and its needs from individual as well as interpersonal perspectives. Data collected within this context frames a Family Assessment. This data adds a critical dimension to one’s interactions with the patient and their family. The Family Assessment is a tool that provides contextual details about the objective information obtained in the genogram, which was collected during the patient’s history. Family Assessment also can clarify immediate and extended familial relationships as well as social and community networks that might impact family-focused care. These assessment data help the provider work as a partner with the family in meeting their primary care needs (Artinian, 1994).

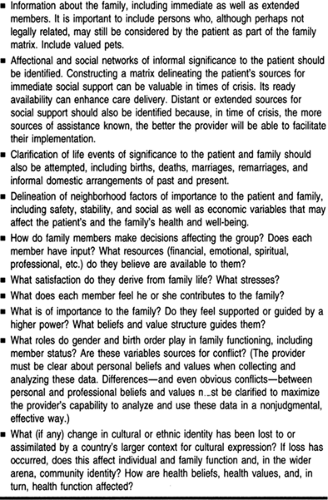

There are several published family assessment tools. Appendix 2-2 presents a sample Family Assessment tool designed and used by the author. This instrument can be used as is, or modified to fit practice needs. Regardless of which tool one ultimately uses, several areas are key to collecting data that is complete. It is important to note the role played by culture and ethnic traditions in family functioning. Important areas for collecting data in family assessment are summarized in Table 2-1.

A Family Circle is the first step in Family Assessment. As such, this data should be appended to the family assessment. The process for gathering a Family Circle diagram is quick and straightforward (Thrower et al, 1982). The provider gives the patient a pen and paper, prompting them to date it and then draw a circle which represents the family. The patient draws smaller circles inside and/or outside this larger circle, representing the patient, individual family members, and, if desired, any significant relationships including pets. As it is constructed by the patient, the circle illustrates the emotional relationships inherent in their family matrix. A Family Circle diagram serves as a visual aid for a patient’s perception of the direction and importance of relationships at the point in time in which it

was drawn. Each circle’s size can be interpreted to mean an individual’s significance, while distance between circles may indicate the extent of affection felt for or closeness to that family member. The patient may want to write a brief statement which describes their feelings about the circles and their meaning. The provider and patient then discuss the Family Circle diagram together, with the patient confirming and/or explaining the Circle’s interpretation. This subjective data can be extremely valuable to the provider’s overall Family Assessment. Figure 2-1 illustrates a Family Circle for Case # 1, that of the family of the young woman diagnosed with breast cancer. Figure 2-2 presents the family in Case # 2, with the elderly man with dementia. Figure 2-3 represents the family of the young patient with asthma presented in Case # 3. The role of community resources is demonstrated in each Family Circle diagram.

was drawn. Each circle’s size can be interpreted to mean an individual’s significance, while distance between circles may indicate the extent of affection felt for or closeness to that family member. The patient may want to write a brief statement which describes their feelings about the circles and their meaning. The provider and patient then discuss the Family Circle diagram together, with the patient confirming and/or explaining the Circle’s interpretation. This subjective data can be extremely valuable to the provider’s overall Family Assessment. Figure 2-1 illustrates a Family Circle for Case # 1, that of the family of the young woman diagnosed with breast cancer. Figure 2-2 presents the family in Case # 2, with the elderly man with dementia. Figure 2-3 represents the family of the young patient with asthma presented in Case # 3. The role of community resources is demonstrated in each Family Circle diagram.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree