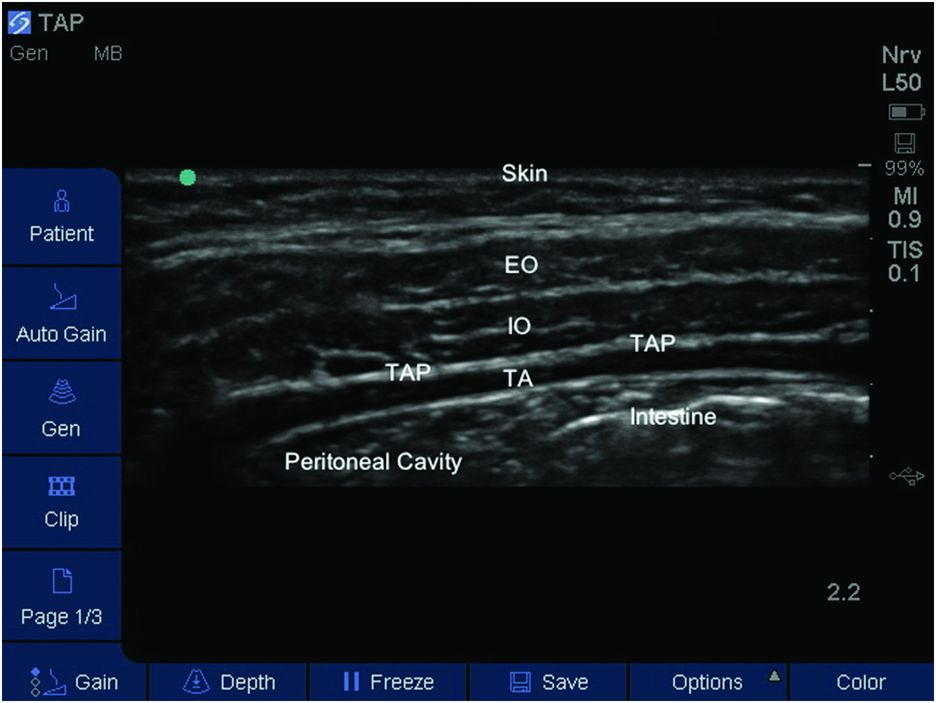

Sonoanatomy for transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block.

Labeled sonoanatomy for TAP block. EO, external oblique muscle; IO, internal oblique muscle; TA, transversus abdominis muscle; TAP, transversus abdominis plane.

The skin, muscles, and parietal peritoneum of the anterolateral abdominal wall are innervated by the anterior rami of lower six thoracic nerves (T7–T12) and first lumbar nerve (L1). The terminal branches of these nerves travel in the TAP between the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles.

The TAP block is a compartmental block targeting these nerves as they course through the anterolateral abdominal wall. Deposition of LA impairs nerve conduction resulting in sensory block of the anterolateral abdominal wall (skin and parietal peritoneum) (McDonnell et al., 2007). In clinical practice, the extent of the sensory block is variable, probably as a result of anatomic differences in nerve distribution and communication, technique used, site of needle insertion, and volume of LA injected.

Landmarks

Hebbard first described a lateral approach to the ultrasound-guided TAP block in adults (Hebbard, 2007). With the patient in the supine position, Hebbard recommended a transversely oriented probe on the anterolateral abdominal wall. Following identification of the TAP, the probe is moved posteriorly to the mid-axillary line, above the iliac crest. The needle tip is then directed posterior to the mid-axillary line prior to infiltration of LA, which can be visualized in real-time.

However, as this technique only reliably produced analgesia below the umbilicus, Hebbard went on to modify his approach to perform an “oblique subcostal” TAP block in 21 adult patients (Hebbard, 2008). He suggested placing the ultrasound probe perpendicular to the abdominal wall, parallel to the costal margin and oblique to the sagittal plane. The needle is introduced close to the xiphoid process in-plane with the probe, and LA is infiltrated between the transversus abdominis and rectus abdominis muscles. Hebbard then directed the needle infero-laterally to progressively distend the TAP. However, it must be pointed out that excessive needle movement potentially increases the risk of vascular and/or neural injury.

A further modification by Suresh and Chan was described in 2009 to overcome the difficulty in identifying the relevant sonoanatomy described by Hebbard in the oblique subcostal approach in newborns and infants (Suresh and Chan, 2009). The authors recommend placing a “hockey-stick” ultrasound transducer immediately lateral to the umbilicus to first identify the posterior rectal sheath and the rectus abdominis muscle. From that position, the probe is then moved laterally toward the flank where all three layers of the abdominal musculature are easily seen, becoming aponeurotic before the lateral border of latissimus dorsi and the origin of the transversus abdominis come into view. The reported benefit of this approach was to potentially allow for better spread of the drug to the entire abdominal wall as the local anesthetic was deposited closer to the origin of the thoracolumbar roots (Suresh and Chan, 2009).

Until further data in children are available, a reasonable site for injection is slightly posterior to the mid-axillary line with the probe position adjusted to obtain the best view of all three muscle layers (Figure 15.3). This lateral approach is described below. Upper abdominal incisions may be best served by the oblique subcostal approach or a rectus sheath block at that level.

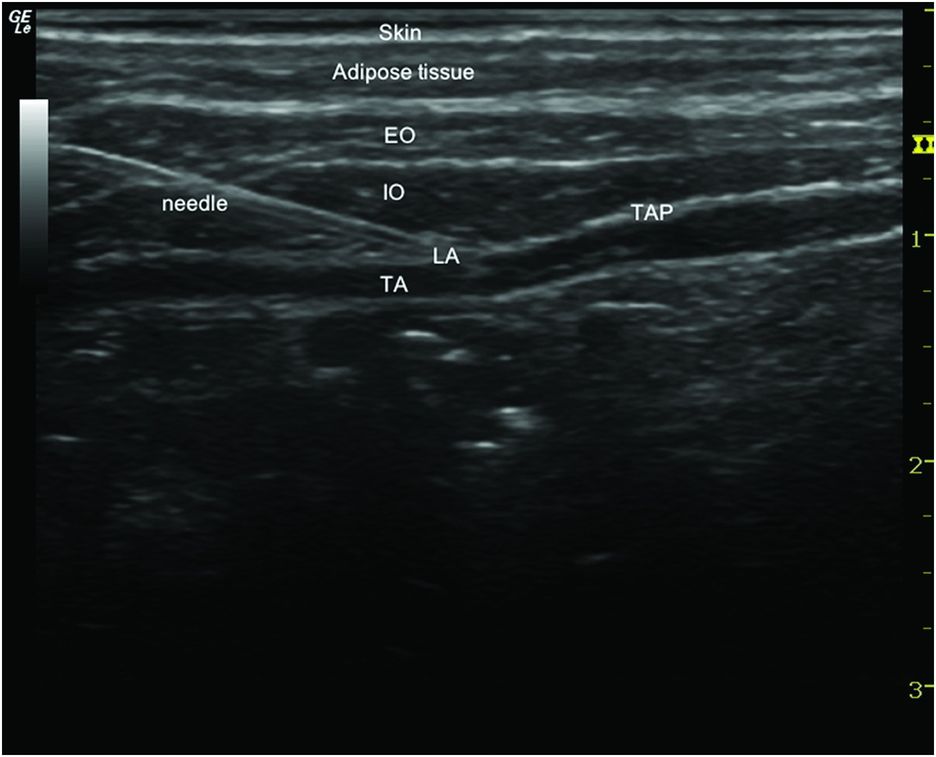

Patient position, probe placement, and in-plane needle approach.

Data from the adult population suggest the posterior approach is more beneficial for surgery below the umbilicus, with the subcostal approach more suitable for upper abdominal incisions.

Block performance

For a posterior TAP block the transversely oriented probe is placed on the anterolateral abdominal wall between the costal margin and the iliac crest over the anterior axillary line (Figure 15.3). Once the three muscles of the anterior abdominal wall are identified, the probe is translated posteriorly to identify the origin of the transversus abdominis muscle, beneath the latissimus dorsalis muscle.

The needle is introduced in-plane at the medial aspect of the transducer in a medial to lateral orientation. A “pop” sensation may be appreciated as the needle passes through the plane between the external oblique and internal oblique, and again as it passes into the plane between the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscle (Figure 15.4). Then, 1–2 ml of LA solution is injected to confirm correct location of the needle tip, which should appear hypoechoic on ultrasound. If the injection appears intramuscular, the needle tip is withdrawn or advanced by 1 or 2 mm before another aliquot of 1–2 ml is infiltrated to ensure location of the needle tip within the TAP. The drug of choice is a long-acting amide LA, such as bupivacaine 0.2% or ropivacaine 0.2%, and total LA dose should not exceed accepted safe maximal doses.

In-plane needle approach for TAP block. EO, external oblique muscle; IO, internal oblique muscle; LA, local anesthetic; TA, transversus abdominis muscle; TAP, transversus abdominis plane.

Current recommended doses for both bupivacaine and ropivacaine in children are 2 mg/kg. The addition of epinephrine to the LA solution may prolong analgesia and reduce peak plasma concentrations.

Post-operative care

The TAP block is a purely somatic block and will not provide analgesia for pain arising from visceral sources. As such, TAP should be considered as one component of a multimodal approach to post-operative pain management.