TRAUMA

| THE EVOLUTION OF TRAUMA CARE IN THE UNITED STATES |

PAST

The history of trauma care is inextricably linked to wars and wounds. Trauma antedates recorded history, and there are examples of anthropological findings showing trepanation of the skull dated to 10,000 BC. These skulls have been found in the Tigress-Euphrates Valley, along the shores of the Mediterranean, and in Meso-America. It is most likely these operations were done for depressed skull fractures, and possibly epidural hematomas. The surgery was most likely performed by priests or shamans within the various cultures. Some of these skulls show that the operation was done more than once; and there is ample evidence that there was success since there was healing of the man-made hole. There is also evidence that they were able to treat fractures and dislocations with successful knitting of the bones.

The first solid evidence for war wounds came from a mass grave found in Egypt and dated to approximately 2000 BC.1 The bodies of 60 soldiers were found in a sufficiently well-preserved state to show mace wounds, gaping wounds, and arrows still in the bodies. The Smith Papyrus records the clinical treatment of 48 cases of war wounds and is primarily a textbook on how to treat wounds, most of which were penetrating. According to Majno, there were 147 recorded wounds in Homer’s Iliad, with an overall mortality of 77.6%. Thirty-one soldiers sustained wounds to the head, all of which were lethal. The surgical care for a wounded Greek was crude at best. However, the Greeks did recognize the need for a system of trauma care, and theirs is one of the first examples of a trauma system. The wounded were given care in special barracks (klisiai) or in nearby ships. Drugs, usually derived from plants, were applied to wounds.

Further east, there was evidence of another trauma system that had been established by the Indian army. This was a system that rivaled that of the Greeks and Romans. India was divided into several kingdoms, and the Far East kingdom was Magadha. It was ruled by Ashoka, the third of the Maurya Dynasty. Ashoka was responsible for developing three sets of documents describing governance, the third of which described some of the care provided to his soldiers when he invaded the kingdom of Kalinga. The Artasastra documented that the Indian army had an ambulance service well-equipped with surgeons and women to prepare food and beverages and to bandage wounds. Indian medicine was specialized and it was the “shalyarara” (surgeon) who would be called upon to treat wounds. Shalyarara literally means “arrow remover,” as the bow and arrow was the traditional weapon for Indians.

The Romans perfected the delivery of combat care and set up a system of trauma centers in all parts of the Roman Empire. These trauma centers were called “valetudinaria” and were built during the first and second centuries AD. The remains of 25 such centers have been found, but importantly, none were found in Rome or other large cities. It is noteworthy that there were 11 found in Roman Britannica, more than currently exist. Some of the valetudinaria were designed to handle a combat casualty rate of up to 10%. There was a regular medical corps within the Roman legions, and at least 85 army physicians are found in the records, mainly because they earned an epitaph.

The concept of shock was not appreciated during this period of time. In fact, it was not until the late 19th and early 20th centuries that shock was finally described.2 The Greeks understood that hemorrhage could lead to death, and they also empirically treated this with herbs, specifically ephedra nebrodensis, which came from Sardinia. The same treatment was used in China, where it was called Ma-Hung, and it was also ephedra. It is most likely that these two distant cultures shared the discovery of ephedra via the “Silk Road.” Hippocrates and Galen did not use the tourniquet. This was partially based on the evidence of Largus, who stated that if you took a pig stomach, filled it with liquid, and then wrapped a rope around it, tightening the rope would increase expulsion of the fluid out of the bag orifice.

Over the first millennium, military trauma care did not make any major advances until midway in the second millennium, just before the Renaissance. Arabic surgery did thrive for two to three centuries, but it was up to French military surgeons, who lived 250 years later, to bring trauma care into the Age of Enlightenment. Ambrose Paré (1510–1590) served four French kings during the time of the French and Spanish civil and religious wars.3 His major contribution to treating penetrating trauma included the treatment of gunshot wounds, the use of ligature instead of cautery, and the use of nutrition during the post-injury period. Paré was much interested in prosthetic devices and designed a number of them for amputees.

It was Dominique Larrey, Napoleon’s surgeon, who addressed trauma from a systematic and organizational standpoint.4 Larrey introduced the concept of the “flying ambulance,” the sole purpose of which was to provide rapid removal of the wounded from the battlefield. Larrey also introduced the concept of placing the hospital as close to the front lines as feasible to undertake wound surgery as soon as possible. His primary intent was to operate during the period of “wound shock” when there was an element of analgesia, most likely due to endorphins, but also to reduce infection in the postamputation period.

Larrey had an understanding of problems that were unique to military surgery and system development. Some of his contributions can best be appreciated by his efforts before Napoleon’s Russian campaign. Larrey did not know which country Napoleon was planning to attack, and there was even conjecture of an invasion of England. He left Paris on February 24, 1812, and was ordered to Mentz, Germany. Shortly thereafter, he went to Magdeberg and then on to Berlin, where he began preparation for the campaign, still not knowing precisely where the French army was headed. In his own words, “Previous to my departure from this capital, I organized six divisions of flying ambulances, each one consisting of eight surgeons. The surgeon-majors exercised their divisions daily according to my instructions, in the performance of operations and the application of bandages. The greatest degree of emulation and the strictest discipline were prevalent among all the surgeons.”

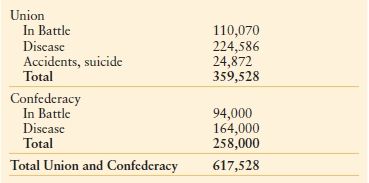

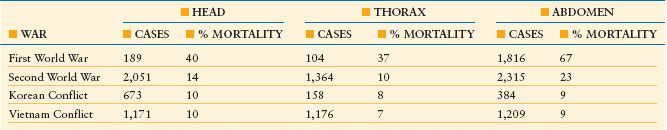

The 19th and 20th centuries were notable in the improvement of surgical care in combat. Antisepsis was introduced during our Civil War, and there was a gradual decline in patients who died from their wounds (Table 20.1) The surgical mortality for head, chest, and abdominal wounds also decreased after the First World War (Table 20.2). Between WWI and WWII, the first civilian trauma system was created in Austria by Böhler. Although initially designed for industrial accidents, by the time of WWII, it also included motor traffic accidents.

TABLE 20.1

CIVIL WAR DEATHS

Data from The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion. Vol. 6, 2nd Issue. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 1875.

TABLE 20.2

SURGICAL MORTALITY FOR HEAD, CHEST AND ABDOMINAL WOUNDS (U.S. ARMY)

Data from Trunkey D. History and development of trauma care in the United States. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;374:36–46.

The most remarkable development of a statewide trauma system occurred early in the 1970s in Germany.5 At that time, road traffic accidents accounted for 18,000 deaths annually. Since 1975, this has been reduced to approximately 7,000. In 1966, two trauma centers were started in the United States: one in Chicago at Cook County (Robert Freeark) and one in San Francisco (F. William Blaisdell). The first statewide trauma system was initiated in 1969 by R.A. Cowley in the state of Maryland. It was at approximately the same time that the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma (ACSCOT) started to develop criteria for trauma systems. In 1976, the first Optimal Criteria document was published, followed shortly thereafter by the ATLS course, which was designed for emergency physicians and surgeons, and defined criteria for resuscitation during the first hour following injury. Subsequently, there were two other significant developments by the ACSCOT, including the Multiple Trauma Outcome Study, which has now gone on to be the National Trauma Data Bank, and a verification program for existing trauma centers. The College recognized early on that the designation of trauma centers was a political and legal process, and the verification program simply examined patient medical records and program improvement documents to verify whether or not the hospital met the designation criteria. By 1995, a report in the Journal of the American Medical Association showed that five states had statewide trauma systems.6 This was followed by another study in 1998 published in the Journal of Trauma documenting that the five states continued to meet all eight previously described criteria for trauma systems7 and 28 states met at least six or seven criteria, whereas an additional four states met at least four criteria. Finally in 2006, another study evaluating the efficacy of trauma center care on mortality showed that the mortality from trauma was 7.6% in designated trauma centers compared to 9.5% in hospitals that were not designated.8 One year after discharge, the significance continued with a mortality of 10.4% versus 13.8%. Another study published in 2006 from Florida showed that in counties with a trauma center, the mean fatality rate was 50% less than in counties without a trauma center.9 It can be seen from this data that the effectiveness of a trauma center is irrefutable as shown by these two recent studies and the data from Germany. Finally, a more recent study shows that trauma centers are more cost effective than hospitals that are not trauma centers.10

PRESENT

I think it is fair to state that the training of a general surgeon over the last 40 years has changed fairly dramatically. To illustrate this, I will compare my own training with the current resident training.

I spent 4 years in medical school between 1959 and 1963 at the University of Washington. During my senior year, I decided that I would go into internal medicine, and did a 3-month sub-internship on the medical wards at Harborview Hospital. At the end of 3 months, I was confused and disheartened because I had not enjoyed internal medicine that much. Unfortunately, there was a paucity of role models in surgery and I applied and got accepted to the University of Oregon in Portland to do a rotating internship. My first rotation was on general surgery with Dr. Dunphy. Within 3 weeks, I had made the decision to pursue surgery as a career. After my internship, I did 2 years in the military and then joined Dr. Dunphy at the University of California San Francisco for my residency between 1966 and 1971. This residency was a true general surgery training program. During that period of time, I did vascular surgery, thoracic surgery, general surgery, and I had 3 months of orthopedic surgery, 3 months of anesthesia, 3 months of pathology, and 2 months of neurosurgery. Following this training, I did an NIH trauma fellowship at Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas with Dr. Tom Shires. This was the same year that I first contacted the American Board of Surgery. I had sent in my cases, which were a little over 1,300. This was again reflective of a general surgery training program at that time. During a 4-month period with Dr. Jack Wiley, I did 137 major vascular cases and this did not include the vascular cases that I did at San Francisco General Hospital or in some of the community hospitals. I turned in almost 80 thoracic cases, of which approximately one-half were due to trauma and half were due to cancer and tuberculosis. I had also done a number of orthopedic procedures, including hip nailings, ORIF of femurs and tibias, and reduction of dislocations. I also had an equally good experience in neurosurgery. After submitting these cases, I did the written exam in November, and after passing this was immediately offered the oral exam in December. Every general surgeon remembers their board examiners, and I am no exception. Fortunately, I passed, and out of the 1,100 candidates that year, the failure rate was 18%. However, two-thirds of these individuals then went on to get specialty training, and the remaining one-third (300 diplomats) stayed in general surgery. How many went into rural practice or urban practice is not a number that I can determine.

Moving forward in time, I would now like to contrast my surgical training and my experiences with the American Board of Surgery. In 1975, I became a guest examiner and received an appointment to the Board in 1980. Interestingly, the same number of total residents was being examined and then this decreased slightly. However, the number that now goes into general surgery is approximately 200. This may be misleading, since a number of people who get specialty training also do general surgery. The year that I came on the American Board of Surgery, the Vascular Board had been just voted in the previous January and for reasons that I cannot explain, they made me chairman of the new certification committee for vascular surgery. This became a very contentious issue. One of the issues that impacted negatively on general surgery training was the decrease in the number of vascular cases residents were allowed to do. This has been compounded recently by the shift of vascular management to endovascular stents and interventional procedures. This has also been exacerbated by the creation of a subspecialty board in surgical oncology, and the separation of cardiothoracic into subspecialty boards of cardiac, thoracic, and pediatric cardiac surgery. Another issue in the 1980s was whether or not to have a certificate for trauma and acute care. Trauma was eventually eliminated from the process due to two surgeons on the board who were vehement that trauma was part of general surgery. Alex Walt argued persuasively that we should still proceed with critical care as a counter to anesthesiology and pulmonary medicine, who he thought would be the only ones who could do critical care if the American Board of Surgery did not provide for this. This eventually came to pass and although we tried to have a common certificate with anesthesiology, pulmonary medicine, and cardiology, this failed. Eventually, the critical care training in surgery became synonymous with trauma. Only time will tell what impact emergency general surgery will have on general surgery training.

Since my initial experiences with the Board, there have been many additional pressures and distractions placed on general surgery, not the least of which is subspecialization within general surgery, including hepatobiliary surgery and pancreatic surgery. Much of this subspecialization is ostensibly done because “experience” leads to better results. However, there is a caveat. In a wonderful article in the British Medical Journal, Sir David Carter made the following comments: “There is now abundant evidence that hospitals with higher volumes of activity tend to have better outcomes and emerging evidence that surgeons’ volume of work is also a determinant of outcome. Certain cancers, cardiac surgery, liver transplantation, and vascular surgery show technical skill is vital, but it is by no means the only essential ingredient for success. Thorough training, compassion, sound judgment, good communication skills, and knowledge are all critically important. However, words of caution are needed. The relation is not linear; some low-volume units achieve good results, whereas higher levels of activity do not necessarily guarantee good outcome.”11 I would ask the question: why can we not teach general surgeons to achieve good results even if they have low volumes?

I articulated in the first portion of this introduction the evolution of trauma centers and trauma systems in the United States. The multiple distractions and pressures against general surgeons are felt keenly by the trauma community. It has been well-documented that many general surgeons, neurosurgeons, and orthopedic surgeons do not want to take trauma call.12 The reasons articulated are busy elective practices that can be negatively impacted following the day after trauma call. Many of the patients do not have insurance and there is a fear of increased malpractice risk when one takes care of trauma patients.13 This has led hospital administrators to initiate on-call pay for general surgeons and some specialty surgeons. This on-call pay varies from $1,000 a shift (general surgeons) up to $7,000 a shift for some of the specialties (neurosurgery). Some of these on-call pay schedules could be interpreted as greed versus need. I recently reviewed the American College of Surgeons data on Level I and II hospitals on the number of emergency procedures done by neurosurgery and orthopedic surgeons within the first 24 hours of admission. In 2008, there was a range of seven craniotomies to 137 craniotomies; the average was 43 per year. In 2009, it ranged from six craniotomies to 137 craniotomies per year, for an average of 62, which is a 50% increase over 2008. For orthopedic cases in 2008, the average was 494 cases with a range of 20 to 1,604. In 2009, it was 558 cases, with a range of 106–1,890. It does not take a mathematical genius to determine that the neurosurgeons average one craniotomy every seven to eight nights, and yet may be paid up to $7,000 a night just to take call. It is highly unlikely that Congress and/or the public will understand or be sympathetic to such payments, particularly with the increasing annual costs in health care and the median total compensation for surgeons. The public might be more sympathetic if hospitals reimburse the surgeons for uncompensated patient care services or assisted specialty groups in recruitment to fulfill trauma care need and obligations.

The Division of Advocacy and Health Policy of the American College of Surgeons has recently come out with a very timely white paper that highlights other issues impacting general surgery.12 In the introduction of the article, it was pointed out that:

- “A majority of surgeons take ED call 5–10 days a month; some surgical specialists take call far more often.”

- “Many surgeons provide on-call services simultaneously at two or more hospitals, and a notable number say they have difficulty negotiating their on-call schedules.”

- “Hospital bylaws typically require surgeons to participate in on-call panels, although older individuals are often allowed to ‘opt out,’ and they are more frequently taking advantage of this option.”

- “A notable number of surgeons have been sued by patients first seen in the ED, and some physicians are offered discounts on their liability coverage if they limit or eliminate ED call.”

The Advocacy and Health Policy Division goes on to point out the importance of emergency rooms as a safety net for patients and their role in trauma care. A study by the Lewin group in 2002 showed that neurosurgeons, orthopedic surgeons, general surgeons, and plastic surgeons were among the specialists in short supply for emergency department (ED) call panels.14 The Lewin study was confirmed by the Schumacher Group in 2003, reporting that one-third of EDs lacked surgeon specialty coverage, causing 76% of those responding to go on divert status.15 More recently, similar surveys were conducted by the American College of Emergency Physicians in 2006, and they showed that nearly three-quarters of ED medical directors think that they have inadequate on-call specialist coverage, compared with two-thirds in 2004.16 In the most recent survey, orthopedic, plastic, and neurologic surgeons, as well as otolaryngologists and hand surgeons, were reported as most often being in short supply. The American College of Surgeons Bulletin white paper also points out that surgeons are older, with a noteworthy number taking emergency call at 55 years or older. Furthermore, there is a decrease in surgeons providing charity care. The Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA), which was originally designed as an “antidumping” federal measure, has created a “dumping” problem: an unintended consequence. Finally, malpractice continues to be a problem to any surgeon who provides emergency care.

The crisis in general surgery is further compounded by two studies published by R. A. Cooper, who states, “The physician shortage is here now and will become worse by 2020, when the deficit may be as great as 200,000 physicians.17,18 Many of these will be surgeons, gastroenterologists, and cardiologists.” As noted above, there is a particular crisis in general surgery. Of the approximately 1,000 surgeons who successfully pass their boards, only 200–250 remain in general surgery. Most are getting subspecialty training, and very few of these want to take trauma call. There is also a decline in interest in general surgery because of lifestyle issues, gender, and mentorship. A particularly poignant study by Bland and Isaacs showed a trend toward lifestyle medical specialties rather than surgical specialties.19 There is a fairly dramatic fall from 1978 to 2001 in the interest of fourth-year medical students in general surgery. Orthopedics may have slightly increased, but neurosurgery, otolaryngology, and urology have stayed relatively flat. There is a particular issue as it relates to gender. Graduating medical students are at least 50% female, and very few apply to general surgery (7% or a little more than 500 applicants). Part of this disinterest in general surgery is the hours of work during the surgical residency, part of it is lifestyle, part of it is a desire to combine a professional career with a traditional role as a mother, and part of it because the programs have not provided protective time so that they can do both. However, there seems to be some recent positive changes in application to surgical programs since the institution of the 80-hour work week.

Recently, the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma, working in concert with the American Board of Surgery, has proposed a solution to attracting medical students into trauma and critical care surgery and retaining them once they pass their boards. The proposed solution essentially expands trauma and surgical critical care to also include emergency general surgery. To accomplish this, it is most likely that surgeons would have to rotate in shifts to cover the hospital 24 hours a day. This might be particularly attractive to women and single parents who would have more control of their time, since they could do 12- to 13-hour shifts a month, leaving the rest of the time for parenting.

Another major problem by 2020 will be the 30% increase in the elderly population in hospitals. It used to be that the peak in death rate from injury was in the 16- to 24-year age group. We are now seeing a bimodal distribution, with an increased death rate in the elderly. The elderly are more active, and unfortunately, the mortality rate for Injury Severity Score >15 is 3.5 times more than those of their younger counterparts.20 These patients spend more time in the intensive care unit, and unfortunately, do not always have a good return to independent living status or quality of life after their trauma episode.

The lack of general surgeons also impacts negatively on the Department of Defense (DOD) and its need for surgeons.21–25 Approximately 20% of DOD surgeons are active-duty surgeons; 80% must come from the reserve. Studies after Desert Storm by the General Accounting Office showed that surgeons were not being trained properly for trauma, particularly the active-duty surgeons; however, the DOD has improved this during the past 4 years.

Another negative impact on trauma care is that many trauma centers are closing or downgrading their level of care. Since 2003, “dumping” has become an increasing problem for Level 1 and II trauma centers. This phenomenon is characterized by community hospitals calling the trauma centers and speaking to an emergency physician or surgeon, telling them they have a trauma case that they cannot provide care for, either because of a lack of personnel or because the patient’s case is too complex. Many of these patients, once they reach the trauma center, are observed and then discharged the following morning.

Another issue for concern in trauma care is that rehabilitation beds are not available after a severe injury. The General Accounting Office performed a study showing that only one in eight patients with a traumatic brain injury receives appropriate rehabilitation after acute care.10 Rehabilitation is particularly a problem for patients who have no insurance. I had a patient approximately 6 years ago who was 36 years old, married, and had four children—all boys. He started his own construction company, but unfortunately, he did not have enough money to buy health insurance, which would have cost $6,000 per year for a family of six. He fell while constructing a building and became paralyzed. As a result of the accident, his acute care was provided by my hospital free of charge, but we could not find a rehabilitation facility that would take him. We taught his wife the bare necessities of care for a paraplegic, but, obviously, he is at high risk for complications, and home care with his wife performing most of the care will not allow her to work and provide for the family.

There are other issues as well. Of some concern to acute care hospitals is the recent growth in free-standing ambulatory surgery centers. In many instances, these centers are owned by specialty surgeons, and one of the advantages to them is that they do not have to take night call. In addition, they often will not accept patients with Medicaid or Medicare insurance, thus increasing the burden on the “safety net” hospitals

Finally, we must address the issue of specialty surgical coverage to EDs, and specifically those that are designated trauma centers. The lack of consistent coverage, obviously, adversely affects outcomes, and when a hospital diverts, it puts more stress on other parts of the trauma system. Optimally, the solutions would come from professional societies that represent the surgical subspecialties. Not only does this problem apply to trauma centers in this country, but it also has an impact on our ability to deliver trauma care to the military.

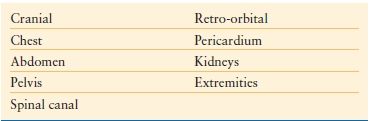

FUTURE

This last section is to ponder on the future of emergency general surgery and trauma surgery. To do so, we have to ask the question: is there a future for trauma in general surgery, and is it good for the community we serve? I think the answer is an unequivocal “yes.” In order for this to happen, however, we have to train a general surgeon who is comfortable working with the neck, chest, abdomen, and is comfortable dealing with vascular injuries and compartment syndromes (Table 20.3) This would include the mangled extremity, and in some instances, emergency neurosurgical and orthopedic procedures.

TABLE 20.3

COMPARTMENT SYNDROMES

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree