Introduction

Sudden cardiac death (SCD) is defined as ‘Natural death due to cardiac causes, heralded by abrupt loss of consciousness within 1 hour of the onset of acute symptoms; pre-existing heart disease may have been known to have been present but the time and mode of death are unexpected’. In this chapter we shall consider causes of sudden cardiac death in adults, how to identify those at potential risk of sudden death, and what treatment options may prevent or reduce the risk of sudden death.

Causes of sudden cardiac death

Sudden cardiac death may occur at any age, but its frequency increases with age and its causes vary with age. Causes may be inherited or acquired (or a combination of both). Coronary atheroma and resulting ischaemic heart disease are the commonest cause of SCD in adults over the age of 35 but other, predominantly acquired, conditions can cause SCD in this age group. Inherited conditions are a less common cause in older adults but predominate as the cause of SCD in people below the age of 35. Table 2.1 lists some of the important causes.

Table 2.1 Some causes of sudden cardiac death.

| Condition | Causes | Further detail |

| Long QT syndromes (LQTS) | Inherited (autosomal dominant) ion channel disorders Many different genotypes but types 1–3 are most common | Predispose to torsade de pointes VT and VF |

| Acquired QT interval prolongation | Drug therapy Ischaemic heart disease Myocarditis | Predisposes to torsade de pointes VT and VF |

| Brugada syndrome | Inherited (autosomal dominant) ion channel disorder | Occurs worldwide but more common in SE Asia. Risk of SCD higher in young males |

| Short QT syndrome (SQTS) | Rare, inherited (autosomal dominant) ion channel disorder | Predisposes to torsade de pointes VT and VF |

| Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT) | Rare, inherited (autosomal dominant) ion channel disorder | Predisposes to torsade de pointes VT and VF, especially on exercise |

| Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) | Inherited (autosomal dominant) | Predisposes to VT and VF |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) | Inherited (autosomal dominant) Several different genotypes | SCD risk is due to VT and VF. Risk varies with genotype and with individual factors |

| Wolff–Parkinson–White (WPW) syndrome | Mostly sporadic Infrequent familial incidence | Not all WPW patients are at risk of SCD. Risk is due to rapid transmission of AF to the ventricles, triggering VT or VF |

| High-grade atrioventricular block | Conducting system fibrosis Calcific aortic stenosis Myocardial diseases including ischaemic heart disease Cardiac surgery Drug therapy Occasionally congenital | Predisposes to ventricular standstill (asystole). Some people with extreme bradycardia develop torsade de pointes VT and VF |

| Severe aortic stenosis | Congenital bicuspid valve (becomes severe at age 50–70 or younger) Degenerative (becomes severe in elderly patients) | If untreated may progress to heart failure or SCD, probably mostly due to VT or VF |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | Probably multiple causes Familial in a minority of cases | Many develop progressive heart failure but there is risk of SCD due to VT or VF |

| Ischaemic heart disease due to coronary atheroma | Partly genetic, partly acquired | SCD risk is mainly due to VT or VF, which may be in response to acute ischaemia or infarction or may be due to previous myocardial scarring |

| Other myocardial diseases | Hypertensive heart disease, sarcoid heart disease, etc. | May predispose to ventricular arrhythmia or AVB in some patients |

| Anomalous coronary artery anatomy | Congenital | Rare cause of SCD in young people, often on exercise. Risk varies with the anomalous anatomical pattern |

SCD = sudden cardiac death; VT = ventricular tachycardia; VF = ventricular fibrillation; AF = atrial fibrillation.

How do people present?

Sadly, many people present by dying suddenly; the first doctor to assess them is the coroner’s pathologist. The autopsy is really important in this tragic situation, because it may provide information that will allow prevention of SCD in other family members. Some inherited conditions that predispose to SCD, such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC), may not be easy to confirm or exclude at a routine autopsy and detailed examination of hearts of SCD victims by an expert cardiac pathologist is recommended. When an autopsy identifies an inherited abnormality, there is an opportunity to screen family members to identify others at risk, in whom treatment may prevent SCD. When autopsy finds no abnormality to explain death, this is regarded as sudden adult death syndrome (SADS). This should always trigger consideration of whether or not there may have been a purely ‘electrical’ inherited cardiac condition that may be present in other family members.

Some people present with ‘failed sudden death’, when a person suffers cardiac arrest from which cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is successful. Increased public access to effective CPR and early defibrillation has increased the incidence of this situation. This provides an important opportunity to assess and offer preventative treatment to the survivor of the arrest and, when there is an inherited cause, to family members at risk. Healthcare professionals involved in successful resuscitation from cardiac arrest and in post-resuscitation care have a unique opportunity to identify individuals with a high risk of further cardiac arrest and those who have an inherited basis for cardiac arrest, with implications for family members.

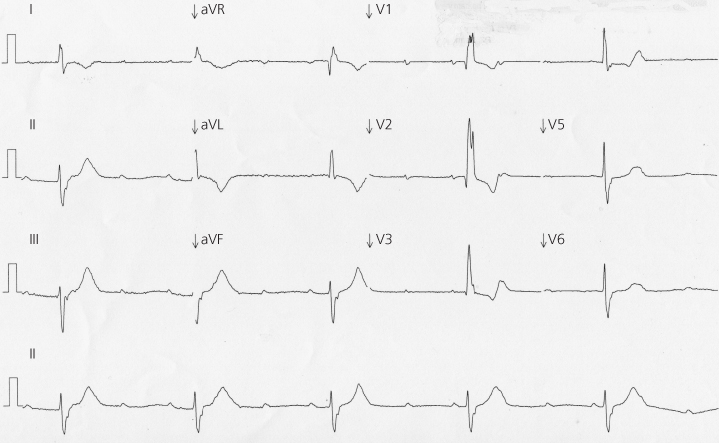

Some people at risk of SCD experience warning symptoms. In people with severe coronary disease the warning symptom is likely to be angina or an acute coronary syndrome. In people with severe aortic stenosis it may be angina, breathlessness or syncope. People at risk of sudden death from cardiac arrhythmia may experience syncope. When someone presents after syncope, they should be assessed to identify features of common problems that do not carry a significant risk of death (such as uncomplicated faints) and to identify a small minority in whom syncope is the only prior warning of a life-threatening but treatable problem. This problem might be, for example, high-grade atrioventricular block (AVB), as shown in Figure 2.1, in which a pacemaker will protect against SCD, or an inherited cardiac condition predisposing to ventricular arrhythmia, requiring an implanted cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) in some patients.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>