Introduction

Arrhythmias are common in the peri-arrest period: they may lead to cardiac arrest or they may occur soon after return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), a time when the myocardium is frequently ‘electrically unstable’. Arrhythmias that may lead to cardiac arrest or to avoidable deterioration in the patient’s condition require urgent treatment; others may require no immediate treatment. When an arrhythmia is present or suspected, the patient is first assessed using the ABCDE approach, which will include applying an ECG monitor and, whenever possible, recording a 12-lead ECG. The patient is assessed for presence or absence of adverse features and an attempt is made to diagnose the arrhythmia.

All defibrillator energy levels given in this chapter refer to biphasic waveforms.

Adverse features

The presence or absence of adverse symptoms or signs will dictate the urgency and choice of treatment for most arrhythmias (Box 13.1).

- Shock—Hypotension (systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg), pallor, sweating, cold, extremities, confusion or impaired consciousness

- Syncope

- Heart failure

- Myocardial ischaemia—chest pain and/or evidence of myocardial ischaemia on 12-lead ECG

- Extremes of heart rate: tachycardia >150 min−1; bradycardia <40 min−1

In general, the presence of adverse features implies the need for more rapid treatment: in some cases, a simple clinical intervention, such as a vagal manoeuvre, may be effective but more commonly there is some form of electrical intervention (cardioversion for tachyarrhythmia or pacing for bradyarrhythmia). In the absence of adverse features, assuming treatment is indicated, the use of drugs is usually appropriate.

If a patient develops an arrhythmia as a complication of some other condition (e.g. infection, acute myocardial infarction, heart failure), that condition is assessed and treated as appropriate.

Tachyarrhythmia

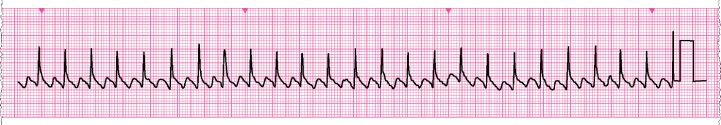

The adult tachycardia algorithm is shown in Figure 13.1.

Figure 13.1 The adult tachycardia algorithm. Reproduced with the kind permission of the Resuscitation Council (UK).

Tachycardia with adverse features

The presence of adverse features implies that the patient’s condition is unstable and the preferred treatment is likely to be synchronised cardioversion. Although a heart rate of >150 min−1 is considered an adverse sign, patients with impaired cardiac function, structural heart disease or other serious medical conditions may be symptomatic with heart rates between 100 and 150 min−1.

Synchronised cardioversion

Before cardioversion is attempted, the patient will need to be anaesthetised or sedated by a healthcare professional with the appropriate competencies.

Set the defibrillator to deliver a synchronised shock; this delivers the shock to coincide with the R wave. An unsynchronised shock could coincide with a T wave and cause ventricular fibrillation (VF).

For a broad-complex tachycardia or atrial fibrillation, start with 120–150 J and increase in increments if this fails. Atrial flutter and regular narrow-complex tachycardia will often be terminated by lower-energy shocks; therefore, start with 70–120 J.

If cardioversion fails to terminate the arrhythmia, and adverse features persist, give amiodarone 300 mg i.v. over 10–20 min and attempt further synchronised cardioversion. The loading dose of amiodarone can be followed by an infusion of 900 mg over 24 h given preferably via a central vein.

Tachycardia without adverse features

If there are no adverse features, consider treatment with a drug. Some anti-arrhythmic drugs may cause myocardial depression or another tachyarrhythmia, or provoke severe bradycardia.

Broad-complex tachycardia

Broad-complex tachycardia (QRS ≥ 0.12 s) may be ventricular in origin or may be a supraventricular rhythm with aberrant conduction (i.e. bundle branch block). In the patient with adverse features, the distinction is irrelevant—the treatment is to attempt synchronised cardioversion. In the absence of adverse features, next determine whether the rhythm is regular or irregular.

Regular broad-complex tachycardia

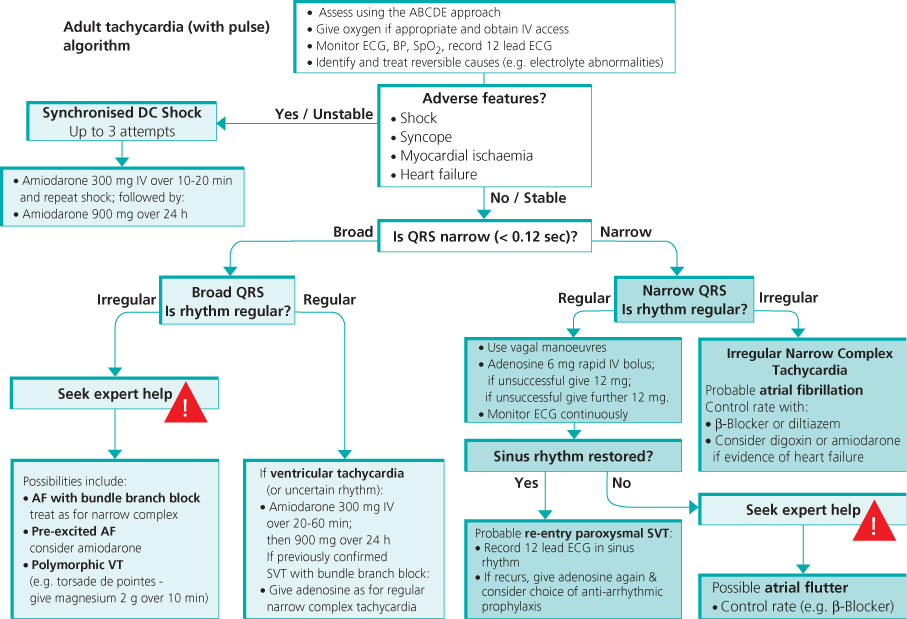

A regular broad-complex tachycardia may be ventricular tachycardia (VT) (Figure 13.2) or supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) with bundle branch block. In a stable patient, adenosine, when given during a continuous, multi-lead ECG recording, may help to determine the rhythm by causing AV block and demonstrating the underlying atrial rhythm if the rhythm is of supraventricular origin. If the rhythm is VT, adenosine will have no effect on heart rhythm or rate. If VT, give amiodarone 300 mg i.v. over 20–60 min, followed by 900 mg over 24 h. If a regular broad-complex tachycardia is known to be SVT with bundle branch block, and the patient is stable, treat as for narrow-complex tachycardia.

Figure 13.2 Monomorphic ventricular tachycardia. Copyright © 2012 Dr Oliver Meyer, Reproduced with permission.

Irregular broad-complex tachycardia

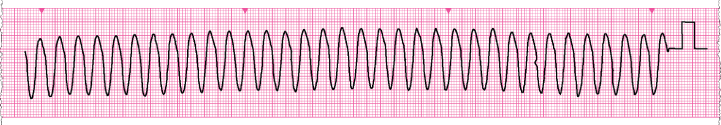

This is most likely to be atrial fibrillation (AF) with bundle branch block but less common causes are AF with ventricular pre-excitation (in patients with Wolff–Parkinson–White (WPW) syndrome), or polymorphic VT (e.g. torsade de pointes) (Figure 13.3). Polymorphic VT is likely to be associated with adverse features.

Figure 13.3 Polymorphic ventricular tachycardia—torsade de pointes. Copyright © 2012 Dr Oliver Meyer, Reproduced with permission.

If the rhythm is torsade de pointes, stop all drugs known to prolong the QT interval, correct electrolyte abnormalities (especially hypokalaemia) and give magnesium sulphate 2 g i.v. over 10 min. Once the arrhythmia has been corrected, seek expert help because overdrive pacing may be indicated to prevent relapse. If adverse features develop, which is common, give a shock. If the patient becomes pulseless, attempt defibrillation immediately and follow the cardiac arrest algorithm.

Narrow-complex tachycardia

Regular narrow-complex tachycardias include sinus tachycardia, atrioventricular nodal re-entry tachycardia (AVNRT; the commonest type of regular narrow-complex tachyarrhythmia), atrioventricular re-entry tachycardia (AVRT; due to WPW syndrome) and atrial flutter with regular atrioventricular (AV) conduction (usually 2:1).

An irregular narrow-complex tachycardia is most likely to be AF, or sometimes atrial flutter with variable block.

Regular narrow-complex tachycardia

Sinus tachycardia

Sinus tachycardia is a common physiological response to stimuli such as exercise or anxiety. In a sick patient it may reflect pain, infection, anaemia, hypovolaemia, or heart failure. Treat the underlying cause.

Paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia

Atrioventricular nodal re-entry tachycardia is the commonest type of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (SVT), often seen in people without any other form of heart disease. It is uncommon in the peri-arrest setting. It causes a regular, narrow-complex tachycardia, often with no clearly visible atrial activity on the ECG. The heart rate is usually well above the upper limit of normal sinus rate at rest (100 min−1). It is usually benign, unless there is structural heart disease or coronary disease.

Atrioventricular re-entry tachycardia occurs in patients with the WPW syndrome, and is also usually benign, unless there is additional structural heart disease. The common type of AVRT is a regular narrow-complex tachycardia, usually with no visible atrial activity on the ECG.

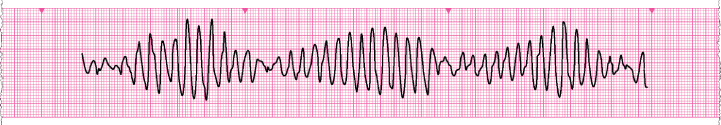

Atrial flutter

This produces a regular narrow-complex tachycardia. Typical atrial flutter has an atrial rate of about 300 min−1, so atrial flutter with 2:1 conduction produces a tachycardia of about 150 min−1 (Figure 13.4). Much faster rates (160 min−1 or more) are unlikely to be caused by atrial flutter with 2:1 conduction. Regular tachycardia with slower rates (125–150 min−1) may be caused by atrial flutter with 2:1 conduction, usually when the rate of the atrial flutter has been slowed by drug therapy.

Figure 13.4 Atrial flutter with 2:1 atrioventricular block. Copyright © 2012 Dr Oliver Meyer, Reproduced with permission.