Resuscitation in sport

Cardiac arrest occurring during sporting activity is fortunately relatively rare. Most cases are non-traumatic (80%) and occur in young males. Of these non-traumatic causes, 90% are cardiac in origin (Table 20.1). Over the past 30 years the incidence of cardiac arrest during sporting activity has increased, with cardiovascular disease being the main aetiology. The term sudden cardiac death (SCD) is used to describe such an event and is defined as ‘natural death due to cardiac causes, heralded by abrupt loss of consciousness within one hour of the onset of acute symptoms; pre-existing heart disease may have been known to have been present but the time and mode of death are unexpected’ (European Society of Cardiology). In athletes this can occur both during competition and training and the incidence varies: in high school and college athletes, studies from the USA report 0.5 cases per 100,000 athletes, where as in some areas of Italy, the incidence is as high as 3.6 cases per 100,000. Under the age of 35 years, the aetiology is predominantly congenital or inherited abnormalities, whereas over the age of 35 years, the vast majority are caused by coronary artery disease. Within this latter group, there is a 10-fold increase in incidence amongst those who engage in infrequent vigorous exercise, with 1:1500 ‘joggers’ sustaining sudden cardiac death compared with 1:50,000 marathon runners, and males are ten times more likely to be affected than females. The more common cardiac causes of cardiac arrest are covered below (see also Table 2.1 in Chapter 2).

Table 20.1 Aetiology of cardiac arrest in athletes.

| Non-traumatic (80%) | |

| Cardiac (90%) | Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy Congenital coronary artery anomalies Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (AVRC) Ischaemic heart disease Ion channel disorders |

| Non-cardiac (10%) | Heat stroke Asthma Illicit drugs Intracranial haemorrhage |

| Traumatic (20%) | |

| Neurological | Head or cervical spine injury |

| Cardiovascular | Haemorrhage Commotio cordis |

| Respiratory | Tension pneumothorax Pulmonary contusion |

| Others | Lightning strike Drowning Suicide |

Non-traumatic cardiac arrest

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM)

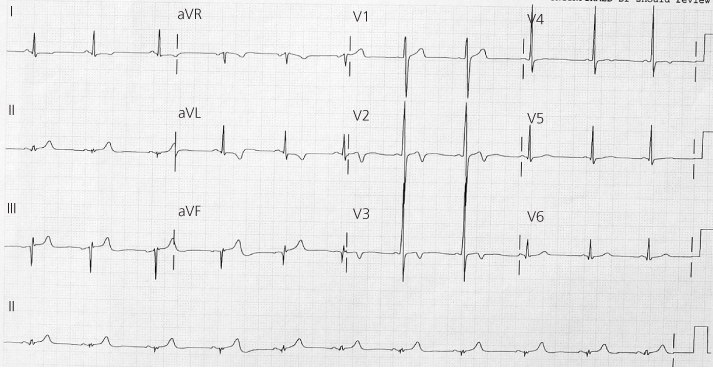

In most parts of the world, HCM is the commonest cause of SCD during sport, the exception being Italy (see below). It is an inherited cardiac abnormality, autosomal dominant with variable expression, affecting around 0.2% of the population resulting in hypertrophy of the interventricular septum and anterior wall of the left ventricle. At a cellular level, there is hypertrophy of individual myocytes and myocardial fibre disarray, the degree of which predisposes to electrical re-entry and sudden death. Unfortunately, the first evidence of HCM in an athlete is often at autopsy, after a cardiac arrest during exercise, due to a ventricular arrhythmia. Occasionally, syncope may occur after exercise as a result of a ventricular tachyarrhythmia, left ventricular outflow obstruction reducing cardiac output, a paradoxical fall in blood pressure or a vasovagal attack. A routine 12-lead ECG will show abnormalities in more than 90% patients; these may include left axis deviation, abnormal T-wave inversion, patholological Q waves, and increased R- or S-wave amplitude in the anterior chest leads (Figure 20.1).

It is important that this condition is not confused with ‘athlete’s heart’ where significant changes are induced as a result of extreme training. The European Society of Cardiology recognises the following as training-related ECG changes: sinus bradycardia, first degree heart block, incomplete right bundle branch block, early repolarisation and isolated left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) by voltage criteria. Other changes favouring the diagnosis of athlete’s heart include a reduction in LV mass after a short period of deconditioning, a LV end-diastolic diameter greater than 55 mm (compared with less than 45 mm in HCM) and normal Doppler-derived indices of LV diastolic filling and relaxation. Cardiac MR imaging may be of value in the diagnosis of HCM by detecting segmental LV hypertrophy and delayed gadolinium enhancement, due to fibrotic replacement of myocytes, and also in those patients in whom poor echo images are obtained.

Congenital coronary artery anomalies (CCAA)

This is the second commonest cause of SCD in athletes, usually due to the left main coronary artery arising from the right sinus of Valsalva. One theory is that because the artery passes between the aorta and the pulmonary trunk, it is compressed as the aorta expands during exercise. Victims may present with exercise-induced ischaemia (chest pain) and syncope (arrhythmias); however, their resting ECG may be normal.

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC)

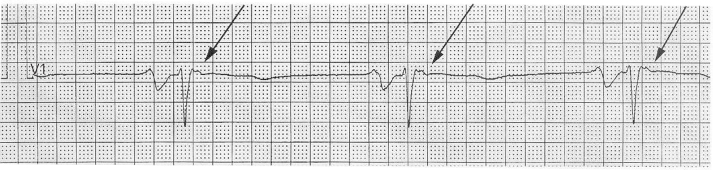

This is an inherited disorder, autosomal dominant, and 30–50% of victims have a family history. It seems to be particularly prevalent in Italy, most probably as a result of a pre-participation screening programme whereby athletes with HCM have been identified and prevented from participation in sport, thereby changing the apparent aetiology of SCD. AVRC causes progressive atrophy of the myocytes with fibro-fatty replacement, usually within the free wall of the right ventricle. The commonest initial presentation is syncope with ventricular tachycardia (VT). There are various associated ECG abnormalities: T-wave inversion in leads V1–3, right bundle branch block, presence of an epsilon wave (a notched deflection after the QRS complex) (Figure 20.2), and frequent premature ventricular contractions on a 24-h ECG recording.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>