Introduction

Most in-hospital cardiac arrests (IHCAs) are predictable events associated with slow and progressive deterioration in the patient’s cardiac, respiratory and neurological function due to a non-cardiac problem. Overall survival to hospital discharge following IHCA in adults is < 20%. Therefore, measures aimed at preventing IHCA are essential to improving outcome for at-risk patients.

Demographics of IHCA

The distribution of IHCA usually depends upon the hospital’s proportion of intensive care unit (ICU) and high-dependency care unit (HDU) beds. These beds are usually equipped with continuous or automated patient vital signs monitoring. Hospitals with a high proportion of ICU and HDU beds tend to have a greater proportion of cardiac arrests occurring in monitored patients. In hospitals with few such beds, most arrests occur in unmonitored patients and are usually also unwitnessed. Irrespective of arrest location, the primary cardiac arrest rhythm in hospital is usually either asystole or pulseless electrical activity (PEA).

Outcome following in-hospital cardiac arrest

Only about 15–20% of patients suffering an IHCA survive to hospital discharge. Survival is better if the arrest occurs in a monitored area, is witnessed, or the victim has a shockable rhythm (i.e. ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia). Most adult survivors of IHCA are defibrillated immediately. Many IHCA survivors have a full return of neurological status to pre-arrest levels, but approximately 40% may have moderate or severe neurological disability. Although cardiac arrest is rare in hospitalised pregnant women and children, the underlying causes are similar and outcomes are similarly poor.

Predisposing factors

Hospitalised patients with an admission diagnosis of heart disease may suffer a cardiac arrest caused by a sudden change in cardiac rhythm due to an irritable myocardium. However, most IHCAs occur during non-cardiac illness and are heralded by unrecognised, or untreated, respiratory and circulatory deterioration due to the patent’s underlying admission diagnosis, associated complications or coexisting diseases (e.g. hypertension, diabetes mellitus, renal disease).

IHCA is rare in pregnant women, but when it occurs it can often also be linked to a failure of prompt recognition of physiological deterioration by hospital staff. Specific risks that may predispose to deterioration include pre-existing medical conditions, maternal sepsis, eclampsia and obstetric haemorrhage. In children, cardiac arrest due to primary cardiac disease is extremely rare. More often profound hypoxaemia and hypotension are the cause, with asystole or PEA being the most common initial arrest rhythms.

The role of ‘false’ arrests

A ‘false’ arrest can be defined as an IHCA call for which no cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is needed. This usually occurs when one of the following exists: (a) a cardiac arrest call is cancelled by the hospital telephone exchange soon after having been made; (b) the patient is found to have been dead for some time and no CPR is undertaken by the resuscitation team; or (c) the patient is found not to have suffered a cardiac arrest. The false arrest is often caused by one of the conditions shown in Box 3.1. Particular attention should be paid to patients who have a ‘false cardiac arrest’, as the event often signifies unrecognised illness. The subsequent hospital mortality for patients suffering a false cardiac arrest is approximately 20–30%.

- Vasovagal collapse

- Chest pain

- Respiratory depression

- Morphine overdose

- Postoperative bleeding

- Tachycardia

- Bradycardia

- Hypoxia

- Sudden reduction in conscious level

- Seizures

Other factors influencing the occurrence of IHCA

Adequate patient monitoring and assessment are crucial to preventing adverse outcomes, such as IHCA. Ideally, the sickest patients should be admitted to areas that can provide the greatest supervision and the highest level of nursing care and organ support. Higher nurse–patient staffing ratios are associated with a reduction in IHCA rates. IHCA survival rates are lower during nights and weekends. Hospital processes, such as admission to hospital at night or at weekends, or discharge from an ICU to a general ward at night, also increase the risk of cardiac arrest and death.

Structuring systems to prevent patient deterioration and cardiac arrest in hospital

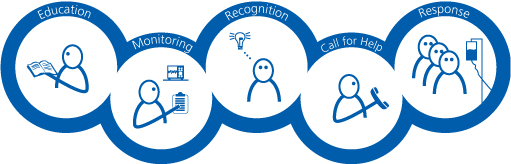

The essential components of a system for preventing patient deterioration and IHCA are described by the ‘chain of prevention’ and shown in Figure 3.1. Each component is represented by a ring in the chain. The rings are education, monitoring, recognition, call for help and response.

Figure 3.1 The chain of prevention (from Smith GB. In-hospital cardiac arrest: Is it time for an in-hospital ‘chain of prevention’? Resuscitation 2010;81:1209–11.). Reproduced by permission of Professor Gary B. Smith. Copyright © 2012 Gary B. Smith.

As no chain is stronger than its weakest link, failure (or absence) of one or more of its components (rings) will inevitably result in failure of the whole system. This will be manifested by patient deterioration and cardiac arrest. If the components of the chain are present and strong, the chain will work perfectly, and this should be measureable as a reduction in the number of preventable IHCAs.

The first ring of the chain of prevention: staff education

Research suggests that some medical and nursing staff do not possess the knowledge, skills or confidence to deal with acutely ill patients in general hospital wards. Often there is a failure to use a systematic approach to the assessment of critically ill patients; poor communication; a lack of teamwork and insufficient use of treatment limitation plans. Evidence of reduced IHCA rates after educational interventions is emerging.

Hospitals need to ensure that their staff have the necessary competencies to recognise the signs of patient deterioration and to manage the acutely ill patient. The exact competencies required will vary between staff groups, but all members of clinical staff should be competent to undertake the activities shown in Box 3.2.

- The ability to observe patients correctly and to measure and record patient’s vital signs

- The knowledge to interpret observed findings

- The ability to recognise the signs of deterioration

- The ability to use an early warning scoring system or ‘calling criteria’

- The ability to appreciate the level of clinical urgency required by a given situation

- The ability to use simple interventions (airway opening, oxygen therapy, intravenous fluid administration, etc)

- The ability to work successfully as part of a multiprofessional team

- The ability to organise care appropriately

- The knowledge of how to seek help from other staff

- The knowledge to use a systematic approach to information delivery, e.g. RSVP or SBAR

- The ability to initiate or facilitate discussions about ‘do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation’ (DNACPR) decisions and end-of-life (EoL) care

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree