Sleep and Fatigue

Timothy C. Flynn

CASE SUMMARY

Dr. W is a CA-2 resident in a university anesthesiology residency program. He has had a rough week. One of the other residents assigned to the service was on vacation, and Dr. W was on call 3 nights in the last 7 days. Of course, he was supposed to leave by noon the next day, but with the in-service examination coming up and a new baby at home, he was not getting much sleep during his time off. He had been up all last night with a series of trauma cases, one of whom had died on the table after several hours of intensive effort by the entire team. He was exhausted and was looking forward to the weekend, which he had entirely off. His mother-inlaw was coming in to care for the baby, and he and his wife were going to the beach. He thought about taking a nap before driving home, remembering the lecture from his program director on sleep impairment, but he was really anxious to get started with his time off. At the first stoplight after leaving the campus, his head nodded, and the driver in the car behind him blew his horn to get him to move once the light had turned green. Dr. W opened the car window and turned up the radio. As he was nearing the exit to his home, he was unaware of the 4-second microsleep that overtook him, just enough time for him to drift into an oncoming sport utility vehicle (SUV).

Dr. W is a 53-year-old anesthesiologist in a small town. He is one of the founding partners of a fourman group that is the sole anesthesia provider for a busy, mostly elective surgery hospital. Unfortunately, one of his partners recently suffered a heart attack and was recovering from angioplasty. He and the other two partners were taking call every third night. This was usually not a big issue, but this week had been unusually busy with cases posted in all the operating rooms (ORs), and so after their nights on call, the partners were also doing long days in the OR. Last night he had been up all night with epidurals for labor and a bowel obstruction. He was tired, but did not want to burden his colleagues or disappoint the patients, surgeons, or hospital. Besides, he remembered those long days as a resident where working 36 hours straight was just part of the drill. He remembered this case very well. It was a 2-year-old child with a routine inguinal hernia. He prepared for the case as usual, but for reasons he still cannot explain, made up the concentrations in his drugs 10 times the concentration appropriate for a 2-year-old. As he sat in the office talking to his lawyer, the only thought that came to mind was that he was too tired to pay attention to the details.

Why Should I Be Concerned About Sleep Loss and Fatigue?

At no time in the history of medicine has the emphasis on safe care been more pronounced than now. Spurred by high-profile reports by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) and sensational instances where the health care system has failed to provide even the most rudimentary safeguards of patient well-being, the profession and the public are demanding that we look at the systems we work in and eliminate as many barriers to safety as possible. One topic that resonates with the public is that of sleep loss and fatigue in health care providers. Lack of sleep and fatigue are really separate entities, but with considerable overlap. They most often exist together in the clinical settings in which physicians find themselves. Sleep deprivation can be acute and/or chronic, resulting from busy schedules, frequent interruptions in sleep cycles, or medical conditions. Fatigue is the other side of the same coin and results from emotional exhaustion, long stretches of work demanding high levels of performance, or chronic illness. Regardless of the longstanding traditions in medical training and practice, the public have an intuitive sense that someone who has worked for 36 hours straight or who routinely works 110 hours a week simply cannot reliably perform at peak effectiveness. Most people find the current residency rules of 80 hours a week to be beyond their own capability and know how bad they feel trying to do their jobs on less than adequate rest. Recent news magazines have spotlighted the state of chronic sleep deprivation, from

which much of the population suffers, and listed the negative effects on performance resulting from lack of sleep. Those who come to us for care are acutely aware of this issue and expect us to place their interests over our own. The negative effects of sleep loss and prolonged time on task are well recognized in aviation, trucking, railroads, the military, and other industries where legislation is in place to limit hours worked. As physicians, it becomes an issue of professionalism to inform ourselves about the effect of sleep loss and fatigue and ensure that our systems of care do not force individuals to work beyond their physiologic limits.

which much of the population suffers, and listed the negative effects on performance resulting from lack of sleep. Those who come to us for care are acutely aware of this issue and expect us to place their interests over our own. The negative effects of sleep loss and prolonged time on task are well recognized in aviation, trucking, railroads, the military, and other industries where legislation is in place to limit hours worked. As physicians, it becomes an issue of professionalism to inform ourselves about the effect of sleep loss and fatigue and ensure that our systems of care do not force individuals to work beyond their physiologic limits.

Despite the obvious conclusion that patients deserve a well-rested caregiver, the issue of how to achieve this goal is a complicated one. The logical conclusion is to limit the number of hours that physicians are allowed to work. In contrast, physicians are taught to value total dedication to the individual patient, regardless of the time of day or how many hours it takes. This sense of personal responsibility is thought to be essential to the best care that can be offered and is deeply embedded in the culture of residency and practice. Nevertheless, less altruistic forces are also at work in the current system; there is a strong economic incentive to see as many patients and do as many procedures as possible. Enforcing strict limits on working hours may have unintended consequences and not lead to safer care, but may increase risk due to frequent hand-overs, loss of continuity, decreased experience in residency, and possible restricted access to physicians with limited skills. Furthermore, focusing on time worked as the only metric may distract attention from other embedded safety hazards in the environment. As in every discussion in healthcare, the trade-off between cost and outcome needs to be factored into the equation of safe care. At the least, physicians should be aware of the role that sleep and the effects of sleep deprivation and time on task have on performance. Physicians should be able to apply strategies to their practice to help reduce the impact of less than perfect sleep habits.

Why Do We Sleep?

No one really seems to know why animals on this planet sleep. Studies show that even fruit flies sleep and when they are deprived of sleep, they develop a sleep debt that will be made up at the next opportunity to sleep.1 Sleep is a complex phenomenon where active processes occur that lead to the health of the organism. Experts have debated on what is essential about the sleep period. However, most agree that sleep is a period of repair and restoration of key functions such as wakefulness, energy expenditure, and learning. Researchers have described the architecture of sleep and identified several stages that occur in cycles of 90 to 120 minutes through the sleep period. Early cycles have more deep, or Stage 4, sleep than cycles later in the typical sleep period. Older individuals seem to spend less time in Stage 4 sleep, and therefore may have a harder time recovering from sleep loss. Contrary to popular belief, older individuals do not need less sleep. Disruptions in either the quantity or quality of sleep can lead to excessive daytime sleepiness and impairment in tasks that require vigilance and judgment. Although there is some variation in the number of hours of sleep needed, the consensus is that most of us need 7 to 9 hours of continuous sleep in each 24-hour period.2 Despite claims to the contrary, there is almost no one who can sustain performance in the face of a chronic reduction in the number of hours slept per night. Likewise, sleep that is disrupted by frequent periods of arousal is associated with a decline in function. In addition to work schedules that deprive individuals of sleep or result in frequent interruptions, there are more than 80 medical conditions and countless medicines that can contribute to the impairment of sleep. Physicians are just as subject to these problems as is the population at large. Although there is considerable individual variation in the magnitude of the negative effects of sleep deprivation on performance, it is not reasonable to assume that physicians are somehow a selfselect group immune to the physiologic rules that govern sleep in the rest of humanity.

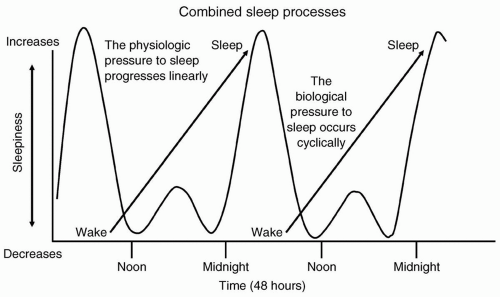

As soon as you awaken from sleep, you begin to build up a sleep deficit (see Fig. 67.1). This propensity to sleep is related to your baseline sleep conditions and influenced by the intensity of daily activity. In normal circumstances, as the day progresses, the pressure to sleep increases until the individual cannot sustain wakefulness under any circumstances. This homeostatic process can only be reset by a period of sleep. In addition, physiologic processes controlled by the brain come into play. Humans evolved on a planet with light and dark cycles. Artificial lighting and the need to function in a 24/7 manner are relatively recent additions to the human condition. As such, we are governed by the circadian rhythms hard-wired into our bodies. An endogenous rhythm of body temperature, hormonal output, and alertness lasting slightly longer than 24 hours persists, regardless of external influences such as work schedules or travel. Nadirs in these factors typically occur in the early afternoon between 3:00 PM and 5:00 PM, and in the early morning between 3:00 AM and 5:00AM (Fig. 67.1). The relationship and feedback mechanisms between sleep homeostasis and circadian rhythms are complicated but, suffice it to say, the combination of sleep deprivation and circadian rhythm disturbance can be additive in reducing the ability to perform complex tasks. For the individual clinician trying to manage his or her own performance in the face of demands that were not anticipated by evolutionary necessity, awareness of the inescapable limits of human performance is essential.

What Are the Effects of Sleep Deprivation?

▪ ACUTE SLEEP DEPRIVATION

Much of what has been written about the effects of sleep deprivation has been learned through controlled

laboratory experiments. Although it can be argued that these studies have little relevance to clinicians faced with the adrenalin-charged atmosphere of an acute emergency situation, it is hard to deny that much of what physicians do is not performed in that context, but in a situation where the stimuli are not so compelling. Subtle lapses in performance in these situations, especially when repeated, can lead to a poor outcome for the patient. In general, individuals subject to acute sleep loss exhibit mood changes, irritability, difficulty in concentration, memory lapses, decreased attention to detail, and difficulty in performing complex or time-sensitive tasks.3 After 24 hours of wakefulness, studies show that decreases in performance and alertness is greatest in the 6:00 AM to 10:00 AM time frame. In residency, this is the time we frequently ask the students to be in conference and expect them to retain the information presented. Likewise, this is the time when the highest numbers of drowsy-driving accidents occur. A survey of interns showed that they were more than twice as likely to be involved in a motor vehicle crash after a 24-hour shift as those interns whose work did not include the extended shifts.4 Performance in driving tasks after 16 hours of wakefulness is comparable to a blood alcohol level of 0.05 to 0.1%.5 A recent study has shown that needle-stick injuries in interns are more common after extended work shifts and during the night hours. Lapses in concentration and fatigue were cited as the most common contributing factors.6 Other experiments show that deficits in attention, working memory, and executive function tasks deteriorate after 16 hours without sleep.7

laboratory experiments. Although it can be argued that these studies have little relevance to clinicians faced with the adrenalin-charged atmosphere of an acute emergency situation, it is hard to deny that much of what physicians do is not performed in that context, but in a situation where the stimuli are not so compelling. Subtle lapses in performance in these situations, especially when repeated, can lead to a poor outcome for the patient. In general, individuals subject to acute sleep loss exhibit mood changes, irritability, difficulty in concentration, memory lapses, decreased attention to detail, and difficulty in performing complex or time-sensitive tasks.3 After 24 hours of wakefulness, studies show that decreases in performance and alertness is greatest in the 6:00 AM to 10:00 AM time frame. In residency, this is the time we frequently ask the students to be in conference and expect them to retain the information presented. Likewise, this is the time when the highest numbers of drowsy-driving accidents occur. A survey of interns showed that they were more than twice as likely to be involved in a motor vehicle crash after a 24-hour shift as those interns whose work did not include the extended shifts.4 Performance in driving tasks after 16 hours of wakefulness is comparable to a blood alcohol level of 0.05 to 0.1%.5 A recent study has shown that needle-stick injuries in interns are more common after extended work shifts and during the night hours. Lapses in concentration and fatigue were cited as the most common contributing factors.6 Other experiments show that deficits in attention, working memory, and executive function tasks deteriorate after 16 hours without sleep.7

▪ CHRONIC SLEEP DEPRIVATION

In the clinical situation, we frequently experience acute sleep deprivation superimposed on a background of chronic sleep loss. Workplace studies of physicians attempting to compare acute sleep loss to baseline are often contaminated because, even at baseline, most subjects are in a chronic state of sleep restriction. Early studies purported to show that individuals could “adapt” to sleep loss and preserve function. In retrospect, these studies were likely flawed by lack of appropriate control groups, small sample size, and unrecorded use of naps and/or stimulants (caffeine). More recent studies show increasing deficiencies in performing psychomotor tests of vigilance as the duration of sleep restriction progresses. Likewise, memory tasks and cognitive throughput performance fall off in relation to the amount of sleep lost. After 14 nights of only 6 hours of sleep per night, performance approximates that of 48 hours of total sleep deprivation.2 Mood swings, depression, loss of empathy, and burnout are also consequences of chronic sleep deprivation.8 A commonly used tool to assess sleepiness is the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (see Table 67.1).9

▪ FATIGUE

Complaints of fatigue among health care workers are common and may be the result of anything from cancer to mental illness. Fatigue is often described as lack of energy, tiredness, difficulty concentrating, or loss of motivation—many of the same complaints seen with sleep deprivation. Although a complete discussion of fatigue is beyond the scope of this chapter, it should be noted that the same working conditions that lead to sleep deprivation can also lead to fatigue and burnout. Individuals whose working conditions involve long periods of intense concentration and physical demands require a time for rest and relaxation. Reluctance to take time off for vacation, or even sick leave, is seen as a badge of honor in many specialties. However, working harder and longer is not necessarily working better or safer. Working in situations where there is a lack of control

over the volume and acuity of work also contributes to increasingly less efficient performance. Anesthesiologists are understandably vulnerable to this situation by the very nature of their work. Professionals in particular wish to be involved in work that they find rewarding and varied. The classic triad of burnout—emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and lack of a sense of personal accomplishment—leads to a downward spiral where both work performance and personal life suffer.

over the volume and acuity of work also contributes to increasingly less efficient performance. Anesthesiologists are understandably vulnerable to this situation by the very nature of their work. Professionals in particular wish to be involved in work that they find rewarding and varied. The classic triad of burnout—emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and lack of a sense of personal accomplishment—leads to a downward spiral where both work performance and personal life suffer.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree