Acute Liver Dysfunction and Anesthesia-Induced Hepatitis

Phillip S. Mushlin

Stuart B. Mushlin

Richard D. Olson

CASE SUMMARY

A 67-year-old woman with adenocarcinoma was admitted to the hospital for a right hemicolectomy. She had two uneventful surgeries under halothane anesthesia more than 20 years earlier. Her personal and family history was negative for liver disease. She had no allergies, had not traveled recently, and had no history of alcohol or illicit drug use. Liver chemistry tests obtained 7 weeks earlier were normal, and imaging studies were negative for metastatic disease.

The surgery was performed under general anesthesia with propofol, fentanyl, desflurane, and vecuronium. Surgery lasted 70 minutes and was uneventful. Postoperative pain management included Percocet (Endo Pharmaceuticals, Chadds Ford, PA) and ibuprofen. On postoperative day (POD) 5, the patient developed jaundice, malaise, and anorexia, without a rash, pruritus, or eosinophilia. Alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and total bilirubin (2,188 IU per L, 425 IU per L, 18 mg per dL, respectively) were markedly elevated, but alkaline phosphatase (AP) was normal. Abdominal ultrasonography showed gallbladder sludge, without biliary dilatation. Serum tests for iron, copper, ceruloplasmin, hepatitis viruses (A, B, and C), cytomegalovirus, and autoantibodies (i.e., antimitochondrial, antismooth-muscle, and antinuclear antibodies) were normal. Tests showed seropositivity for IgG for herpes simplex and Epstein-Barr’s viruses, consistent with prior infection.

On POD 8, AST and ALT began to decrease, but the coagulopathy and jaundice worsened, and encephalopathic changes occurred. While the patient was being evaluated for orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT), her condition suddenly improved. All clinical and laboratory abnormalities had resolved by POD 21, and the patientwas discharged home with a diagnosis of desflurane-induced hepatitis.

Is This a Case of Desflurane-Induced Hepatitis?

What information is needed to diagnose anesthesia-induced hepatitis (AIH)?1,2 The diagnostic issues are complex. Various interventions and events are well-recognized antecedents of perioperative liver injury, such as adverse drug reactions and ischemic hepatitis. Preexisting diseases are another important consideration; advanced or incipient diseases that are unrecognized preoperatively (e.g., clinically silent) may declare themselves postoperatively, with a time course indistinguishable from AIH. Examples include viral hepatitis, steatohepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, and pregnancy-related diseases. This chapter focuses on the diagnosis of AIH within the context of confounding variables that may lead to misdiagnoses. We also address the treatment and prevention of AIH.

Do Halogenated Anesthetics Cause Liver Necrosis?

▪ CHLOROFORM

The potent halogenated vapors are the only anesthetic agents that have engendered concerns about postoperative liver dysfunction. In 1912, The American Medical Association issued a condemnation of chloroform anesthesia due to fatal cases of liver failure associated with the use of this agent.3 The term delayed chloroform poisoning (or “hepatic necrosis”) was generally taken to represent a distinct pathologic entity. However, there was never scientific proof of a causal link between chloroform anesthesia and postoperative liver injury during the seven decades of its popularity. In fact, most deaths attributed to chloroform anesthesia were from cardiac—rather than from liver—complications.4

▪ HALOTHANE

An alarming number of cases of anesthesia-associated liver failure occurred a few years after halothane’s entry into the clinical arena. This prompted the Committee on Anesthesia (of the National Academy of Sciences-National Research Council) to investigate postoperative hepatic necrosis. Hoping to clarify the matter quickly, the committee abandoned the idea of a randomized clinical

trial in favor of a retrospective review known as the National Halothane Study.5

trial in favor of a retrospective review known as the National Halothane Study.5

National Halothane Study

This study is a testament to the difficulty of collecting useful information about anesthetics and postoperative liver injury. It was a colossal epidemiologic undertaking—a review of 856,515 general anesthetics from 1959 to 1962, including 16,840 deaths and 10,171 autopsies. Its two main goals were to determine the rates of mortality from: (i) surgery and general anesthesia and (ii) fulminant hepatic necrosis within 6 weeks of anesthesia and surgery. The study—despite its enormity—identified just 82 deaths from liver necrosis, and many of these were clearly unrelated to anesthesia. The death rate from massive liver failure was 1 in 10,000 surgical anesthetics (i.e., 82 in 856,515) overall and was lower in the halothane group (1 in 35,000) than in the other anesthetic groups (i.e., cyclopropane, ether, nitrous oxide, barbiturate).

The conclusions of the study were that anesthesia rarely leads to death from liver failure, and that halothane is associated with a lower mortality rate than other anesthetics. However, readers should be circumspect for several reasons. First, the study uses retrospective data which are inherently susceptible to investigator bias. Second, the variability in halothane use (i.e., 6.2% to 62.7%; mean = 30%) and mortality rates (0.27% to 6.41%) among the 34 institutions that contributed data was huge. Third, protocol restrictions caused a high proportion of substantive observations to be excluded from the study. For example, approximately 40% of the deaths (that occurred within 6 weeks of surgery) could not be evaluated for massive liver necrosis because no autopsy was performed. And, in 76% of the deaths that involved suspected hepatic necrosis (724 of 946), the data could not be used because of postmortem autolysis (which makes it impossible to evaluate liver histopathology).

The study also dismissed 63% of cases with verified liver necrosis (140 in 222) because the necrosis was less than “massive.” This ignores the fact that submassive liver necrosis can also cause death. The bottom line is that the Halothane Study did not focus on AIH, but rather on fulminant hepatic failure (FHF).6 Nonetheless, the data from this study and others suggest that halothane hepatitis in certain subgroups of patients may occur as often as 1 in 3,000, with a mortality rate as high as 1 in 3,525.7,8,9,10

Do Newer Halogenated Anesthetics Cause Hepatitis?

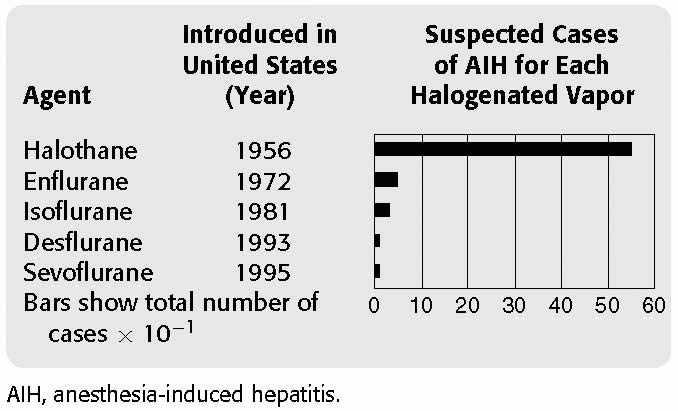

There have been more cases of unexplained postoperative liver injury associated with halothane than with all the other anesthetics combined (see Table 41.1). Not surprisingly, most clinical and laboratory studies on anesthesia-induced liver injury have focused on halothane. Thus, halothane has served as the frame of reference for evaluating the hepatoxicity of the newer anesthetics.

TABLE 41.1 Number of Reported Cases of Anesthesia-Induced Hepatitis | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||

▪ ENFLURANE

Enflurane had been in clinical use for about a decade when Lewis et al.11 published a series of 24 cases of “enflurane hepatitis.” The cases had an uncanny resemblance to halothane hepatitis. Fever was the most common presenting feature. Jaundice occurred in 79% of patients, with a mean latency of 8 days; the latencies were shorter in patients with a history of prior enflurane or halothane anesthesia. Twenty percent of the patients died of FHF.

To Lewis, these cases represented enflurane hepatitis; Eger et al.12 however, were not convinced, so they reevaluated the study data by assigning syndrome scores to each patient in the series. These scores represented a composite of clinical events and outcomes, including fever, chills, nausea, eosinophilia, histopathology, and death. No difference was found between the mean scores of patients with known versus unknown causes of postoperative hepatitis.

This result suggests that enflurane hepatitis lacks distinctive features, and that it is indistinguishable from a failure to identify any of the known causes of hepatitis. Eger’s team opined that even if enflurane had been responsible for every case, enflurane hepatitis would still be an extremely rare entity, with an incidence of <1 in 1,000,000 patients.

▪ ISOFLURANE

Isoflurane has been implicated less often than enflurane as a cause of postoperative liver dysfunction.13,14 Many reports of presumed isoflurane hepatitis have not withstood the scrutiny of an objective review process. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) reviewed 47 cases of suspected isoflurane hepatitis that occurred from 1981 to 1984.15 In most instances, the reviewers identified factors that were more likely than isoflurane to explain the liver injury. These included sepsis, hypoxia, antibiotics, herpes virus, biliary disease, nutritional deficiency, and circulatory shock.

▪ SEVOFLURANE

Concerns about toxic metabolites and byproducts delayed the commercial development of sevoflurane by nearly

two decades. Japan approved sevoflurane for clinical use in 1990, and it became clinically available in the United States in 1995. By then, sevoflurane had a solid record of safety based on its use in operating theaters throughout the world. More than 2 million Japanese patients received the anesthetic during this time, with just four published cases of presumed sevoflurane-induced liver dysfunction.16,17,18,19

two decades. Japan approved sevoflurane for clinical use in 1990, and it became clinically available in the United States in 1995. By then, sevoflurane had a solid record of safety based on its use in operating theaters throughout the world. More than 2 million Japanese patients received the anesthetic during this time, with just four published cases of presumed sevoflurane-induced liver dysfunction.16,17,18,19

What Is the Mechanism of Anesthesia-Related Liver Injury?

▪ PATTERNS OF LIVER INJURY

Two distinct forms of anesthesia-induced liver injury have been described.21 Type 1 leads to mild, transient increases in serum enzymes, which are detectable within hours of surgery and resolve within 2 days. Clinical studies show that levels of serum aminotransferases or glutathione S-transferase may increase in up to 20% to 50% of patients after minor surgery under enflurane or halothane anesthesia.22,23 This type of liver injury is usually benign, self-limiting, and clinically unimportant. Its pathogenesis may involve hepatic ischemia (hypoxia) or cytotoxic effects of anesthetic metabolites. On the other hand, type 2, often referred to as anesthesia-induced hepatitis (AIH) is a rare, idiosyncratic disorder that can lead to massive hepatocellular necrosis, acute liver failure, and death.

▪ CLINICAL FEATURES OF ANESTHESIA-INDUCED HEPATITIS (AIH)

AIH is mainly an affliction of healthy patients which develops following a brief uneventful general anesthetic for minor surgery. The recovery is unremarkable during the first postoperative week—until the syndrome becomes manifest. Among the common early clinical abnormalities are fever, anorexia, nausea, chills, myalgias, rash, and eosinophilia. Jaundice usually develops 3 to 6 days later. This development reflects life-threatening disease, with a mortality rate that may approach 40%.6 Table 41.2 summarizes the clinical features of AIH.

Of the risk factors for AIH, the most important is prior exposure to halothane; 71% to 95% of AIH cases have occurred in this setting.6 The incidence of AIH is 10-fold higher in patients with a history of prior halothane anesthesia than in those who have just had their first-ever halothane anesthetic.21 Short intervals between the two most recent halothane anesthetics have been associated with more severe liver injury. AIH afflicts women more often than men (1.8 to 1), and obesity further increases the risk.24,25 Age is an important but enigmatic risk factor. AIH rarely occurs in children, and one half of the cases have been in people over 50-years-old.21,26,27 Two notable variables that have not been found to be risk factors for AIH are liver disease and perioperative use of potentially hepatotoxic drugs (besides halogenated vapors).28

TABLE 41.2 Features of Anesthesia-Induced Hepatitis | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

▪ THE IMMUNE THEORY OF ANESTHESIA-INDUCED HEPATITIS

Oxidative Metabolites

The generation of reactive intermediates (e.g., trifluoroacetyl chloride) that occurs as the liver metabolizes halogenated anesthetics is central to the immune theory of AIH. There is a strong correlation between the incidence of AIH and the proportion of the anesthetic dose oxidized through cytochrome P450 2E1.29,30 For halothane, enflurane, isoflurane, and desflurane, the proportions oxidized are 20%, 2%, 0.2%, and 0.02%, respectively.31,32,33 Such logunit differences are serendipitous and provide an elegant probe for investigating the role of metabolites in AIH. For example, when subjects receive equipotent doses of the halogenated anesthetics, their livers produce concentrations of metabolites that are dispersed over a 1,000-fold range.

Neoantigens and Autoantigens

These metabolites can covalently bind to various liver macromolecules, forming trifluroacylated derivatives.34 Laboratory studies confirm that equivalent doses (10 MAC-hours) of halogenated anesthetics lead to widely varying amounts of tissue acylation, expressed qualitatively as halothane ≫ enflurane > isoflurane >

desflurane = oxygen.32 In other words, the extent of metabolite incorporation into liver proteins is high with halothane, low with enflurane, even lower with isoflurane, and often undetectable after desflurane anesthesia. The immune system may see the altered liver macromolecules as neoantigens or autoantigens. Attached portions of anesthetic molecules can seemingly act as haptens to foster immune recognition of the carrier proteins. Laboratory and clinical evidence suggest that the immune system targets the altered liver molecules of susceptible individuals as nonself, and mounts an attack on the hepatocytes that can lead to massive liver necrosis.

desflurane = oxygen.32 In other words, the extent of metabolite incorporation into liver proteins is high with halothane, low with enflurane, even lower with isoflurane, and often undetectable after desflurane anesthesia. The immune system may see the altered liver macromolecules as neoantigens or autoantigens. Attached portions of anesthetic molecules can seemingly act as haptens to foster immune recognition of the carrier proteins. Laboratory and clinical evidence suggest that the immune system targets the altered liver molecules of susceptible individuals as nonself, and mounts an attack on the hepatocytes that can lead to massive liver necrosis.

Antibodies to Liver Proteins

Patients with halothane hepatitis have been found to have blood-borne antibodies that target specific liver proteins. Such antibodies have a high affinity for liver proteins isolated from halothane- or enflurane-treated rats, but have little or no affinity for proteins from desflurane- or isoflurane-treated rats.32 These laboratory data reflect the clinical experience with the halogenated vapors; namely, that desflurane and isoflurane are much less likely than halothane to be associated with AIH.

Does Sevoflurane Fit the Immune Theory of Anesthesia-Induced Hepatitis?

Approximately 2% to 5% of the sevoflurane taken up by the body is metabolized through cytochrome P450 2E1. This proportion is much greater than for isoflurane and desflurane, and the rate of metabolism is 1.5 to 2 times faster than for enflurane.33,35,36,37 However, there is a fundamental difference between the metabolism of sevoflurane and the other halogenated vapors. Sevoflurane metabolism—unlike halothane, enflurane, isoflurane, and desflurane—neither produces reactive intermediates nor gives rise to fluroacylated liver proteins, which putatively mediate AIH.19,36,37,38,39 This may explain, at least in part, the lack of association between sevoflurane metabolism and AIH, and the rarity of sevoflurane-related liver dysfunction.33

Immune Crossover and Anesthesia Machines: Are They Relevant to Anesthesia-Induced Hepatitis?

Reports of desflurane-associated hepatitis, which are extremely rare, have included a history of one or more exposures to a halogenated vapor other than desflurane (e.g., halothane). This is a confounding factor as it relates to the immune theory of AIH. For example, the development of hepatitis after desflurane anesthesia in such instances could theoretically result from traces of the inciting agent (e.g., halothane) that entered the patient’s lungs after being aerosolized from the anesthesia machine (where it previously resided). Immune crossover offers an alternative explanation of how earlier halothane (or enflurane) exposures might predispose to liver injury from enflurane, isoflurane, or desflurane anesthetics.40,41,42,43

Are Anesthesiologists at Increased Risk for Anesthesia-Induced Hepatitis?

Liver injury has been reported in both clinicians and laboratory personnel following occupational exposure to small amounts of halothane. For example, an anesthesiologist with suspected halothane-induced liver disease was given subanesthetic doses of halothane in a controlled setting; each administration elicited clinical, laboratory and histopathologic responses that were characteristic of halothane hepatotoxicity.44 Sutherland and Smith45 reported the development of hepatitis in a laboratory investigator exposed to halothane while conducting animal experiments during a 3-year period; the hepatitis promptly resolved after the exposure to halothane was terminated. Another report describes hepatic damage in two surgeons following chronic exposure to subanesthetic doses of halothane; both surgeons were ultimately found to have circulating antibodies that reacted specifically with halothane-altered hepatocyte membrane components.46

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree