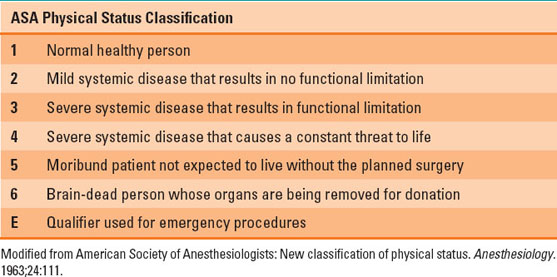

Age alone is not a factor in determining ASA physical status. An ambulatory, fit, cognitively aware 80 year old patient with moderate hypertension is ASA PS 2.

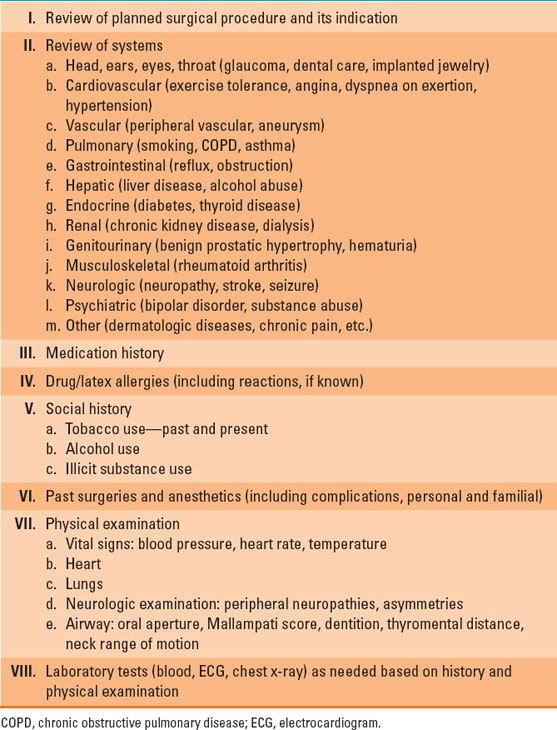

Table 16-1 Components of the Preanesthetic Evaluation

Table 16-2 American Society of Anesthesiologists’ (ASA) Physical Status Classification System

A. Planned Surgery and Its Indication

The planned surgical procedure is an important determinant of the type of anesthesia that will be required for the procedure and the expected level of postoperative pain. The planned procedure also dictates the anticipated patient positioning, blood loss, and monitoring requirements. Understanding the indication for the procedure is important for establishing the risk of postoperative complications. Procedures performed for urgent conditions (e.g., small bowel obstruction, limb ischemia) are associated with an increased risk of perioperative morbidity and mortality.

B. Present and Past Medical History

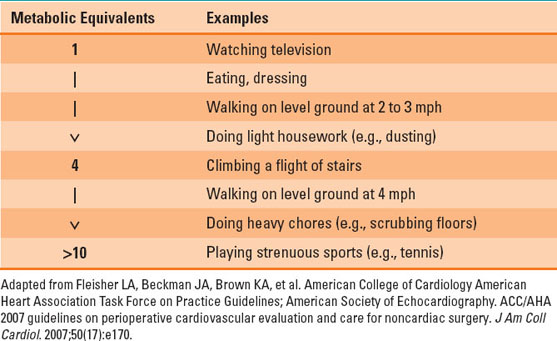

Medical history is best addressed using a systems-based approach. A useful way to screen for occult cardiovascular disease is to inquire about the patient’s ability to exercise at 4 metabolic equivalents (METs) without dyspnea, chest pain, or lightheadedness (Table 16-3). An example of an activity that uses about 4 METs is climbing 1 to 2 flights of stairs. Pulmonary evaluation should take into account a history of asthma or recent upper respiratory infection (URI) and signs and symptoms suggestive of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Asthma or recent URI may predispose the patient to bronchospasm with airway instrumentation, and OSA may signal difficulty with ventilation and the need for increased respiratory monitoring postoperatively. When the review of systems reveals signs and symptoms suggestive of an undiagnosed or uncontrolled medical condition, the patient should be referred to his or her primary care practitioner for further evaluation and management. Whether this workup needs to be completed prior to surgery is at the discretion of the anesthesiologist and surgeon and is often dependent on the urgency and severity of the planned surgical procedure.

Table 16-3 Metabolic Equivalents for Common Physical Activities

Routine referral of presurgical patients to an internist to be ”cleared for surgery” is an unnecessary expenditure. The competent anesthesiologist should only request consultation when it is felt the patient is in need of additional evaluation or treatment prior to surgery.

C. Current Medications and Drug Allergies

Review of current medications, including over-the-counter and herbal or complementary drugs, is an essential component of the preanesthetic assessment, as many drugs used in the perioperative period have important interactions with commonly prescribed pharmaceuticals. Consideration should be given to discontinuation of some drugs with known interactions with anesthetics prior to surgery (e.g, monoamine oxidase inhibitors), but it may be appropriate to continue some drugs into the operative period despite known interactions (e.g., antihypertensives). Additionally, some medications with known rebound side effects when withdrawn abruptly (e.g., propranolol, clonidine) should be continued or tapered slowly prior to surgery.

Cardiovascular Medications

Patients on chronic beta-blocker therapy should continue their medications perioperatively, as abrupt withdrawal may precipitate angina, ischemia, or dysrhythmias. Whether to initiate beta-blocker treatment in patients with known coronary artery ischemia on preoperative stress testing who are scheduled for vascular or other high-risk surgery is a point of much controversy. Too rapid initiation of beta-blocker therapy increases the risk of perioperative bradycardia, hypotension, and stroke. Patients who take centrally acting sympatholytics, such as clonidine, may experience rebound hypertension with abrupt discontinuation. Therefore, it is recommended that these drugs be continued in patients who take them chronically.

There are conflicting results from randomized trials as to whether calcium channel–blocking drugs increase the risk of surgical bleeding; however, it is generally agreed that calcium channel blockers may be continued perioperatively. In the context of major surgery, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blocking drugs (ARBs) have been associated with refractory intraoperative hypotension. For this reason, they are generally discontinued the night prior to surgery, with the caveat that patients who normally take these drugs may be somewhat more prone to postoperative hypertension as a result of their discontinuation. Diuretics are also generally discontinued the night prior to surgery to avoid intravascular volume depletion prior to major surgery where fluid shifts are expected. For more minor procedures, it is probably okay to continue ACE inhibitor, ARBs, and diuretics throughout the perioperative period.

There is evidence that the use of perioperative 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitors (known as statins) reduces cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, especially for patients undergoing vascular surgery. Therefore, it is recommended that statins be continued perioperatively, and consideration should be given to initiating statin therapy in patients with cardiac risk factors who will be undergoing vascular surgery.

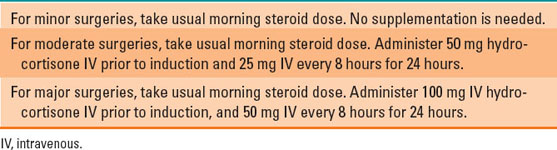

Endocrine Medications

Patients who take glucocorticoids should continue these medications perioperatively. Patients who are on a chronic dose equivalent to prednisone ≥5 mg/day are at risk of adrenal suppression and may require supplemental glucocorticoid administration perioperatively. Table 16-4 summarizes an approach to glucocorticoid supplementation in these patients.

Table 16-4 An Approach to Perioperative Corticosteroid Coverage

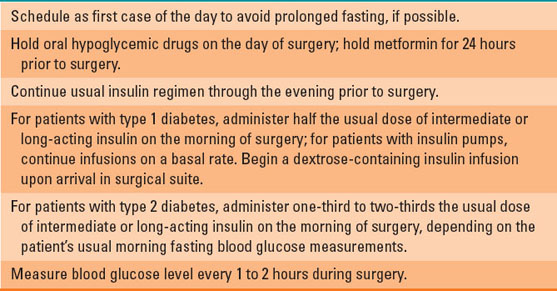

The management of patients with diabetes should be individualized. However, in general, oral hypoglycemic drugs and short-acting insulin preparations should be withheld on the morning of surgery. Intermediate or long-acting insulin preparations should be administered in a reduced dose on the day of surgery. Metformin is associated with an increased risk of lactic acidosis in the context of severe dehydration; therefore, most clinicians discontinue its use a full 24 hours prior to surgery. Table 16-5 presents general guidelines for the perioperative management of oral hypoglycemic drugs and insulin in diabetic patients.

Table 16-5 Guidelines for the Perioperative Management of Patients with Diabetes

Women who take oral contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy are at increased risk for venous thrombosis, owing to the estrogen content in these medications. Therefore, consideration should be given to discontinuing these medications 4 to 6 weeks preoperatively for surgeries associated with a high risk of venous thromboembolism.

The manifestations of severe hypoglycemia can be masked during general anesthesia. While it is desirable to keep blood glucose at near normal levels during anesthesia, the consequences of over treatment with insulin are significant. Frequent perioperative measurement of blood glucose is indicated.

Psychotropic Medications

Although many psychotropic medications have interactions with anesthetic and analgesic agents, most are continued in the perioperative period, owing to the potential consequences of withdrawing these agents in patients with serious mood disorders. Tricyclic antidepressants may cause QTc prolongation and are associated with anticholinergic effects that may be exacerbated by drugs used during anesthesia. Nonselective monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOI), such as phenelzine and tranylcypromine, though rarely used today, pose a special concern in the context of anesthesia. They inhibit the breakdown of monoamine neurotransmitters including dopamine, serotonin, epinephrine, and norepinephrine. In patients taking MAOI, coadministration of indirect acting sympathomimetic agents such as ephedrine may cause a hypertensive crisis. In addition, concomitant administration of drugs with anticholinergic properties, such as meperidine and dextromethorphan, may cause serotonin syndrome, a condition marked by agitation, hyperthermia, and muscular rigidity and caused by an excess of serotonergic activity in the central nervous system.

Mood stabilizing agents, antipsychotics, antianxiety medications, and antiseizure drugs may be continued perioperatively. However, if patients are taking medications with a narrow therapeutic window, such as lithium and valproate, perioperative monitoring of drug blood levels may be appropriate, as drug absorption may be affected by surgery.

Drugs Affecting Platelet Function

Aspirin irreversibly inhibits the platelet cyclooxygenase (COX) enzyme, which is responsible for prostaglandin and thromboxane production. Among its many effects, aspirin inhibits platelet aggregation. For this reason, aspirin is widely used for prevention of clotting in patients at risk for cardiovascular disease, as well as those with a history of angina, myocardial infarction, stroke, and peripheral vascular disease. Daily aspirin therapy is also necessary for patients with coronary artery stents to prevent in-stent thrombosis. In the context of surgery, however, decreased platelet aggregation predisposes patients on aspirin to increased surgical bleeding. Therefore, decisions about perioperative aspirin use must weigh the risk of perioperative hemorrhage against that of cardiovascular complications. It is generally agreed that aspirin should be withheld for 7 to 10 days prior to surgeries where bleeding would have catastrophic consequences (e.g., intracranial, intraocular, middle ear, and intramedullary spine surgeries).

Platelet P2Y12 receptor blockers (e.g., clopidogrel, ticlopidine, prasugrel, ticagrelor) are another class of antiplatelet agents commonly used in patients following an ischemic cerebrovascular event (e.g., acute myocardial infarction) or in patients who have undergone coronary artery stent implantation. Combined use of aspirin and a platelet P2Y12 receptor blocker markedly reduces the risk of in-stent thrombosis in patients with vascular stents. The optimal duration of dual antiplatelet therapy in these patients is unknown; most guidelines recommend that patients who have drug-eluting coronary stents remain on dual antiplatelet therapy for 1 year. If discontinued perioperatively, these medications should be resumed as soon possible. It is suggested clopidogrel and ticagrelor should be stopped 5 days, prasugrel 7 days, and ticlopidine 10 days preoperatively.

It is generally recommended that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents such as ibuprofen and naproxen be discontinued for a period of 3 to 5 days preoperatively, owing to their effect on platelet aggregation. Patients are advised to use acetaminophen as the pain reliever of choice preoperatively, as it has no effect on platelet function.

Oral Anticoagulants

Oral anticoagulants include warfarin, which blocks the production of vitamin K–dependent clotting factors, direct thrombin inhibitors, such as dabigatran, and direct Xa inhibitors, such as rivaroxaban and apixaban. Because the half-life of warfarin is long, it is recommended that warfarin be stopped 5 days prior to elective surgery. When there is a desire to minimize the duration that the patient is without anticoagulation, bridging therapy may be used. This generally involves the administration of low molecular weight heparin, which is usually given via subcutaneous injection and typically commences 3 days prior to surgery, with the last dose administered 24 hours before the start of the procedure. Dabigatran is used primarily to prevent stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation. It has a half-life of about 12 hours in patients with normal renal function, but in patients with kidney disease, its half-life can be more than 24 hours. In patients with normal renal function, dabigatran should be stopped 1 to 2 days prior to surgery; in patients with a creatinine clearance of <50 mL/min, it should be stopped 3 to 5 days prior to surgery. Rivaroxaban and apixaban are less dependent on renal function for clearance and may be stopped 1 to 2 days prior to surgery. Because of their relatively short half-life, bridging therapy is not usually required for the direct thrombin and Xa inhibitors.

Opioids and Medications Used to Treat Addiction

Patients who take opioids for chronic pain should continue these medications perioperatively and often benefit from a pain management plan that includes multimodal treatments such as intraoperative ketamine infusions and regional anesthetic techniques. Patients recovering from opioid or alcohol addiction are sometimes prescribed partial opioid agonists, such as buprenorphine, or opioid antagonists such as naltrexone. These drugs are helpful in addiction recovery because they block the euphoric effects associated with opioid use; however, in the context of surgery, they also interfere with the pain-relieving properties of legitimately administered opioids. As a result, the preferred approached is to discontinue these drugs prior to surgery. This should be performed in consultation with the patient’s primary care physician, recognizing that there is an increased risk of relapse during this period of drug holiday.

Perioperative pain control in patients taking opioids on a chronic basis requires careful planning. Typically these patients are tolerant to opioids and may require extremely high doses of opioids to be rendered comfortable. Concomitant use of regional anesthesia techniques is beneficial.

Herbal or Complementary Supplements

Owing to concerns about their purity and the potential for adverse effects, it is safest to advise that all herbal or complementary drugs be discontinued 1 week prior to surgery. Specific supplements have been associated with particular complications. For example, garlic, ginger, and ginseng may increase bleeding risk. Table 16-6 summarizes the potential side effects of common herbal supplements.

Table 16-6 Perioperative Effects of Common Herbal Supplements

Drug Allergies

Information about drug allergies should be elicited during the preanesthetic interview. It has been reported that 5% to 10% of the population has a penicillin allergy; however, based on prior studies, the majority of these patients (80% to 90%) do not have a true penicillin allergy. Signs and symptoms suggestive of true type 1 immunoglobulin-E–mediated allergy include urticaria, angioedema, and wheezing. Although the potential for cross-reactivity exists between allergy to penicillin and the cephalosporins because of the common β-lactam ring, only about 2% of patients with a documented penicillin allergy will have an allergic reaction to a cephalosporin. Patients should also be asked about a history of allergy to latex, as this allergy requires advance preparation of the operating suite with latex-free equipment.

D. Social History

It is useful to inquire about patients’ tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drug habits, as patients who abuse these substances have an increased risk of complications, including postoperative withdrawal. Smoking is also associated with an increased risk of perioperative respiratory complications, including airway hyperreactivity. In patients in whom a strong suspicion of substance abuse is suspected, urine drug screening on the day of surgery may be indicated.

E. Response to Prior Anesthetics

The preanesthetic interview should include a discussion of any personal or familial history of complications related to anesthesia. Patients should be queried about a personal history of difficult tracheal intubation, prolonged postoperative nausea or vomiting, difficulty associated with spinal anesthesia, and so forth. Each of these scenarios may have important implications for planning an upcoming anesthetic. Malignant hyperthermia is a rare but potentially life-threatening anesthetic-triggered disorder of skeletal muscle metabolism that is often inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion. Patients heterozygous or homozygous for the atypical plasma cholinesterase gene may describe prolonged hospital stays or ventilator dependence after brief surgical procedures. Advanced planning for these patients is a must.

F. Focused Physical Examination

Components of the physical examination of main interest to the anesthesiologist involve the neurologic system, heart, lungs, and airway. Notation of blood pressure and heart rate is useful in screening for undiagnosed or poorly treated hypertension. Auscultation of the heart may reveal murmurs suggestive of cardiac valve abnormalities that require further workup prior to surgery. Wheezing, rhonchi, or other abnormal lung sounds may require follow-up with a chest x-ray or indicate patients who may benefit from pretreatment with bronchodilators or steroids. In patients with a history of congestive heart failure, wheezing may also be indicative of decompensation. It is also important to note pre-existing neuropathies, central nervous system deficits, and skeletal muscle weakness, as these affect the ability to position patients intraoperatively and may affect the decision to perform neuraxial or regional anesthetic blockade.

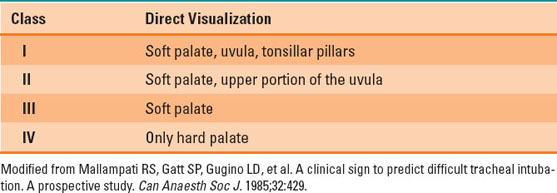

Evaluation of the neck and oral airway helps to determine the potential for difficult ventilation or tracheal intubation and, therefore, preferred methods of perioperative airway management. Basic components of the airway examination include measurement of the oral aperture, Mallampati score, thyromental distance, range of neck motion, as well as examination of dentition and neck circumference. The Mallampati score evaluates the size of the tongue in relation to the oral cavity, and the test is performed by having the patient protrude the tongue while keeping his or her head in a neutral position. The anesthesiologist then grades the view on a 4-point scale based on visualization of the uvula and the soft and hard palate (Table 16-7). Thyromental distance is measured from the tip of the chin (mentum) to the thyroid cartilage, while the patient’s head is maximally extended. A thyromental distance less than 6 cm is suggestive of possible difficult intubation. The patient should also be asked to extend the neck as far as possible (normal is 35 degrees). Significant limitation of neck extension is also a risk factor for difficult intubation. Preoperative evaluation of dentition is important to determine the presence of prosthetics that should be removed prior to anesthesia and to identify pre-existing loose, chipped, or fractured teeth that might later be erroneously attributed to airway manipulation.

VIDEO 16-1

VIDEO 16-1

Airway Exam

Table 16-7 Modified Mallampati Airway Classification

II. Evaluation of the Patient with Known Systemic Disease

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree