PALLIATIVE CARE

In the face of critical surgical illness, palliative care focuses on a set of individualized goals aimed at reducing the suffering of the patient and family members.1,2 Ideally, this process begins prior to the patient’s illness with a personal expression of the person’s end-of-life choices, and extends into the bereavement period following the patient’s death. Realistically, patients rarely begin palliative care planning prior to becoming ill, and most often the process is initiated only after critical illness supervenes or the patient is considered terminal. Rather, palliative care should be integrated as a routine part of the continuum of care in the surgical intensive care unit.3,4 Stated another way, relief of suffering and pain are essential to clinical cure, so the shift from curative to primarily palliative care is largely a change in the goals of therapy.

High-quality palliative care is usually interdisciplinary in nature, and is now a recognized medical specialty. Hospice and Palliative Care Medicine was recognized in 2008 by the American Board of Medical Specialties, with certification in hospice and palliative medicine issued by 10 cosponsoring boards, including the American Boards of Anesthesiology, Emergency Medicine, Family Medicine, Internal Medicine, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Pediatrics, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Psychiatry and Neurology, Radiology, and Surgery.

Considering that palliative care involves crucially important decisions that can be difficult or emotionally wrenching to make, assisting critically ill surgical patients in the transition to palliative care can be challenging for the surgeon. The proposition is no easier for the patient. Thomas Finucane pointed out two fundamental issues that ensure that this transition will continue to be difficult for the patient and his or her family.5 There is a near-universal and fervently held desire to remain alive. Second, in spite of concerted effort, caregivers cannot predict the future sufficiently to provide a meaningful, precise estimate of when death will occur.5 The author would make two additional points: (1) most patients have strong and unique personal beliefs about the nature of death; and (2) from a purely surgical perspective, the surgeon has a strong clinical emotional investment in the patient’s care, most often manifesting as a powerful motivation for the patient to survive the operation. This chapter provides an overview of palliative care as it relates to acute care surgery, trauma, and surgical intensive care.

HISTORY

An urologic oncologist, Balfour Mount, originally coined the term palliative care in the establishment of a clinical service at Montreal’s Royal Victoria Hospital.6 Doctor Mount took inspiration from Elisabeth Kubler-Ross and Cicely Saunders in London.7 The focus of the newly created palliative care unit was to provide comprehensive care of the terminally ill patient.8 This care was aimed at understanding, anticipating, preventing, and alleviating the suffering of the dying patient, which remain the goals of palliative care today.9

PRINCIPLES

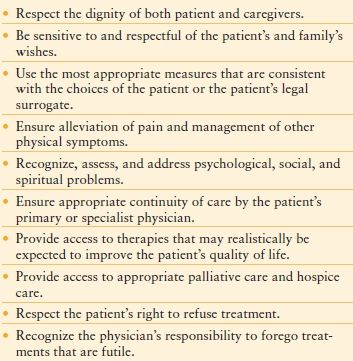

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) Committee on Ethics developed a statement on the principles guiding care at the end of life, which was approved by the Board of Regents and published in the Bulletin of the ACS in 1998 (Table 58.1).10 This statement is a solid resource to the global approach to palliative care. When one reads this statement of principles and reflects on its meaning, it is clear that several crucial points were emphasized: (1) The patient has the right to determine his or her own care, and the surgeon shall respect the patient’s authority to make this choice (including the right to refuse care the surgeon may recommend). (2) The provision of care based on the patient’s choices should address comprehensively pain, psychosocial, family, and spiritual issues. (3) The surgeon should forego treatments that are futile.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

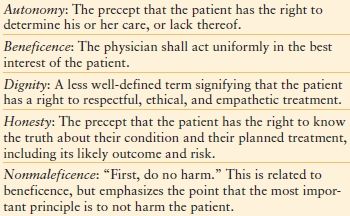

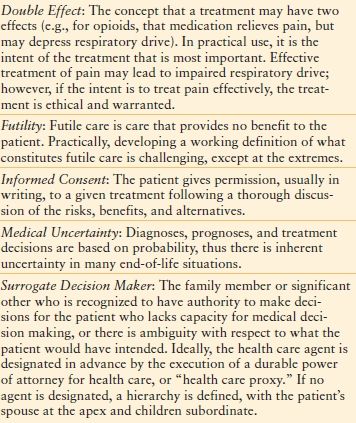

Although this chapter is not a primer on medical ethics, it would be incomplete without a discussion of the general philosophical framework of the principles of both palliative and curative care. The principles may not be held universally by all cultures, but are viewed widely as being applicable universally to decision making relating to the ethical practice of medicine in Western, traditional medicine. The following principles underlie the ethical structure of medical practice and palliative care: 1) honesty; 2) autonomy; 3) beneficence/nonmaleficence; 4) dignity (Table 58.2).11 In addition, several key ethical concepts are relevant to the discussion surrounding palliative care. These include the concepts of futility, informed consent, medical uncertainty, and the principle of double effect (Table 58.3).

TABLE 58.2

DEFINITIONS PRINCIPLES OF RELEVANCE TO PALLIATIVE CARE

TABLE 58.3

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK FOR THE ETHICAL PRACTICE OF PALLIATIVE CARE MEDICINE

Palliative care is often thought of as distinct from traditional curative or supportive care; however, because most modern intensive care is supportive, meaning care that supports organ function until the patient heals, there is a natural continuum whereby palliative care can be integrated into modern intensive care.3,4 For individual patients there may be a clear point of transition from curative to palliative care; however, in some cases the continuum may lead to indistinction, rather than a clear demarcation. For the purposes of discussion, clear transition points serve to illustrate common dilemmas or questions in the intensive care unit (ICU).

When Should Care be Shifted from Curative/Supportive to Palliation?

In patients who are critically ill or who have major, life-threatening, or debilitating surgical and medical problems, the surgical team is often faced with the question of how much curative or supportive care to provide, or alternatively should the goals of care initiate or change to exclusively palliative care?12 In the clinical experience of the author, these questions most often revolve around the principles of autonomy, futility, and beneficence. When the patient has outlined clearly his or her wishes and opinions related to clinical care, the treatment plan should be consistent and respectful of the patient’s wishes, unless care is deemed to be futile. In the case of futility, there is no obligation on the part of the physician to provide futile care. The concept of futility is well described; however, there is considerable disagreement among experts (and applicable laws among the states) as to what constitutes futile care, except in extreme situations (e.g., brain death, anencephaly), so there is commonly disagreement over what constitutes futile care (Table 58.3).

What to Do When the Patient Wishes for Treatment, but Care Is Deemed Futile by the Physician?

This is an inherent conflict between the principle of autonomy and the concept of medical futility. The first course of action should be reassessment of the determination of futility. In most instances, futile care is assessed based on medical probability, for which there is inherent uncertainty. Oftentimes, what seems to be a disagreement over futile care is really a disagreement over the goals of care, so the next course of action should be a respectful, thoughtful, and empathetic discussion between the physician and patient/surrogate(s) concerning the goals of care and a discussion of why the care is not beneficial to the patient. This discussion should include a self-reflective reassessment of the determination of futility, including an objective internal review of biases and potential conflicts (see below).

What to Do When the Patient Wishes No Further Treatment, but the Physician Believes the Care Is Beneficial?

In this situation, the conflict is between patient autonomy and practitioner beneficence—the patient is refusing a treatment that the surgeon considers indicated and beneficial. Again, the best first course of action is a careful self-reassessment. Provided the patient has the capacity to make medical decisions, there should follow an empathetic and respectful discussion between caregiver(s), to understand the patient’s point of view, and patient/surrogate to understand the medical issues involved. For terminally ill patients, once this discussion has been held to the satisfaction of all parties, the patient’s wishes should be followed, regardless of the point of view of the health care team. The patient has the right to make what the clinician may perceive to be an incorrect decision.13

In the author’s experience, this situation is uncommon. Most often the surgical team and the patient/surrogate are in agreement as to when to transition from curative to palliative care. Even when there is disagreement initially, the parties can usually negotiate a mutually agreeable decision. Achieving this harmonious agreement should be a primary goal of the surgical team.

IDENTIFYING POTENTIAL BIAS AND CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

When there is disagreement, it is essential to perform an internal reassessment concerning one’s own beliefs, potential biases, and potential conflict of interests. Even in the absence of any disagreement, it is beneficial to reexamine periodically one’s own potential biases and conflicts of interest. Developing this habit assists with developing a “mindful practice”.14 One would suppose that compared to the patient and his or her family, this process would be easier for the educated, experienced surgeon or intensive care physician; however, sometimes this exercise can be more challenging than one might suppose. The most dangerous bias is one that is unrecognized by oneself. Outlined below are some of the more common potential biases of those working with critically ill patients.

Overconfidence in Predicting Outcome

“Medicine is a science of uncertainty and an art of probability.”15

—Sir William Osler

The longer a doctor has practiced medicine, the less confident he is in his ability to predict the outcome of critical illness; any prognosticator would be well-advised to proceed with caution. Several pieces of data support this conclusion. A prospective, 1-year study of 206 critically ill French oncology patients who were considered for ICU admission found that 101 patients were not admitted: 54 because they were deemed “too sick,” and 47 because they were deemed “too well.”16 Worrisome was that 17% of the “too sick” patients were still alive at 180 days, implying that this group was not terminally ill. Of the group of patients “too well” for admission, 22% were dead in 30 days. Thus the evaluators were not particularly adept at predicting either who would survive or who would not. That the data came from a group of cancer patients, for whom the end of life might seem to be easier to predict as compared to a general surgical or medical population, underscores the difficulty.

In a follow-up to the Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments (SUPPORT), a group of 2,954 critically ill, nononcology patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, or end-stage liver disease were followed after hospital discharge.17 The goal of SUPPORT was to include terminal patients who had an aggregate 6-month mortality rate of 50%. Of these patients, 347 died during the index hospitalization, leaving 2,607 patients who were followed as outpatients. Of these patients, 1,948 (66%) were alive at 6 months. None of the predictive models were accurate for the prediction of who would not survive for 6 months. Using a model predicting a <10% survival rate at 6 months, the actual survival was 41%.

The panoply of critically ill scoring and mortality prediction models (MPMs), including the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE), APACHE II, APACHE III, and APACHE IV scores; the Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS) and SAPS II; the Sequential Organ failure Assessment (SOFA) score; and MPM and MPM II, should raise skepticism. Three points can be made about these mortality prediction tools: (1) Each of these models predicts mortality well for a population of patients. (2) From a temporal standpoint, each is more predictive the closer one comes to death. (3) Most (except APACHE III and SOFA) are not particularly useful to predict the outcome for an individual patient. Therefore, these predictive tools are not particularly helpful when trying to prognosticate for the individual patient.

Among those who care for critically ill patients, bias of overconfidence in predicting outcome can lead to an unjustified, overly pessimistic view or a similarly unjustified, overly optimistic assessment of prognosis. Based on the author’s experience, a personal prognostication is offered: When physicians predict the future, one can usually predict accurately that they will be incorrect. Regardless of the author’s opinion, scientific data clearly support a healthy skepticism concerning one’s ability to predict the outcome of critically or terminally ill patients.

Covenant of Care

Surgeons perform operations upon patients. These operations have a permanent and immediate effect upon the patient’s life. Surgeons and patients partner together to address the problem the operation is designed to remedy. As such, surgeons as a group are invested emotionally in the care of their own patients. Cassel and Buchman described this relationship as covenantal, as a simple promise: “I will care for you.” 18–20 This covenantal relationship is obviously positive, and at least in the author’s opinion, often makes the surgeon the most influential advocate for the patient’s wishes. However, at the end of life, this relationship may lead the surgeon to push for curative care, even when it is against the patient’s wishes. In a hypothetical case discussion regarding informed consent, a group of well-trained, respected, competent surgeons were asked what they would do in the following scenario21: A patient has a soft tissue infection of the foot that is limb-threatening. The consulting surgeon is informed by the patient that death is preferable to amputation, and operation is deferred. The surgeon is consulted again several days later after the patient has become comatose from sepsis and encephalopathy due to a necrotizing soft tissue infection, and lacks capacity to express his or her wishes or make medical decisions. The surgical panelists were unanimous in their agreement that they would amputate the lower extremity in order to save the patient’s life. This was a theoretic panel discussion, but this desire to do the right thing for the patient may lead the surgeon to push curative care in contradistinction to the patient’s expressed wishes. Even the language that is commonly used belies this authority—patients’ “wishes,” and doctors’ “orders.” When one is invested emotionally in the care of a patient, one should take time to reflect personally as to what the patient would choose, and then one should do what one can to honor those wishes. This may or may not be different from the surgeon’s wishes or their perception of what is in the patient’s best interest; clarifying any discrepancy beforehand is decidedly in the patient’s best interest.

Caring for All—Distributive Justice

“Critical care resources are not only expensive, but also scarce.”18 Whereas the patient’s surgeon may have an intensely personal bond with the patient, the acute care surgeon or intensive care physician caring for all patients in the ICU is often placed in the situation of determining the appropriate resource utilization for the case. Even at times of peak ICU utilization, when decision making can be particularly challenging, this responsibility must be recognized and accepted, and should not bias any decisions regarding palliative and curative care, except perhaps in mass-casualty situations. Intensive care is costly and not beneficial for every patient, but recognition of same should not bias care that is in the patient’s best interest. The finite nature of resources is primarily a societal issue that must be addressed at the societal level.

Compassion fatigue, or “burnout,” probably affects all providers of trauma and emergency care at one time or another.22 It is common among those who provide care for terminally ill patients, particularly caregivers who are isolated and overworked. The condition tends to lead to cynicism, anger, and fatigue—a situational depression. If one is mindful of the problem, compassion fatigue can be prevented,22 but when present it may lead to a bias in either direction. Palliative care is best provided by those fully engaged and committed to the comprehensive relief of patient suffering, which is almost impossible under conditions of burnout. A portion of the ACS Manual for the Resident on Palliative Care emphasizes self-care as a component of palliative care.23

The Unbiased Surgeon or Intensivist

The most dangerous bias is the unrecognized bias. Each of us has our own unique biases concerning curative and palliative care based on our own beliefs, values, previous experiences, and fund of knowledge. It is a grave mistake to consider oneself unbiased. This is well told by the late William F. Buckley, describing the story of a man without a country24:

“… It told of a man at a bar who boasted of his rootlessness, derisively dismissing the jingoistic patrons to his left and to his right. But later in the evening, one man speaks an animadversion on a little principality in the Balkans and is met with the clenched fist of the man without a country, who would not endure this insult to the place where he was born.”

So it must be with the unbiased surgeon or unbiased intensive care physician: Being mindful of our own predispositions is crucial to provide reliable guidance and advice for patients and their families when they need it most.

PROVIDING PALLIATIVE CARE IN PRACTICE

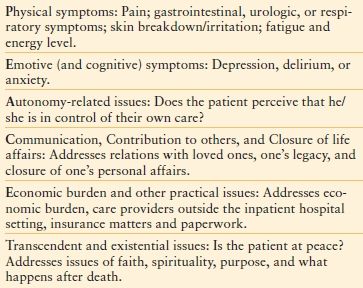

Cicely Saunders25 and Balfour Mount26 emphasized the concepts of the care of the whole patient and relieving all pain as essential elements of palliative care. This approach involves the more traditional domains of relief of symptoms, prevention and treatment of pain, and psychosocial support; however, the palliative approach extends beyond these domains into less traditional areas of spiritualism and existentialism. Eric Cassell broadened this view, emphasizing further that individual patient suffering is unique and is affected by a large number of holistic and subjective domains that extend beyond the typical medical assessment.27

As a tool to assist in addressing these domains in palliative and end-of-life care, several authors have developed tools to assist the clinician. One tool with documented effectiveness to improve care at the end of life is the PEACE Tool (Table 58.4).28

TABLE 58.4

PEACE TOOL

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree