Lyme Disease

Edwin J. Masters MD

Lyme disease (also called Lyme borreliosis) is a multisystem illness caused by the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. It is the most prevalent tick-vectored illness in North America and Europe. The dermatologic and neurologic signs and symptoms were first described in Europe in the early 1900s. In the United States the first report of a case of erythema migrans (EM), the characteristic skin manifestation, occurred in Wisconsin in 1969. The broader clinical spectrum of the disease was recognized in the mid-1970s with the occurrence of a cluster of arthritis cases in the lower Connecticut River Valley town of Lyme, for which the disease was named.

Largely because this complex disease is newly recognized and incompletely studied, knowledge of it has had to be continually updated. This has created confusion and controversy. For example, it was first thought that the etiologic agent was a virus until the causative spirochete was discovered (Burgdorfer et al, 1982). Initially, the disease was termed Lyme arthritis, and “no arthritis, no Lyme” was a common dictum. The illness is now known to be more complex, and the name has been changed to Lyme disease. Arthritis is a common, but not necessary, component.

Patients who fulfill the diagnostic criteria are more numerous and geographically widespread than previously thought. Both seronegativity (Dattwyler et al, 1988; Liegner, 1993) and persistent infection after standard antibiotic therapy have been proven (Preac-Mursic et al, 1989). There has been a trend toward longer and more aggressive antibiotic therapy (Rakel, 1997). The Ixodes dammini deer tick as a separate tick species no longer exists and has been reclassified back to the more widespread Ixodes scapularis (Oliver et al, 1993). Increasing heterogeneity of the spirochetes is now known (Mathiesen et al, 1997), as is the ability of culture media to select or favor certain strains or genotypes (Norris et al, 1997). Failure to obtain a positive culture does not prove absence of infection.

The entire concept of Lyme disease in the lower Midwest and South challenges the prevailing paradigm (Oliver, 1996). Clinically the patients are similar (Masters et al., 1994; Masters & Donnell, 1995), but what to call the condition when the etiologic agent is found to be a related spirochete, but not B. burgdorferi, has not be determined. Regardless of the name, these Southern and Midwestern patients with clinical Lyme disease need to be treated (Masters & Donnell, 1996).

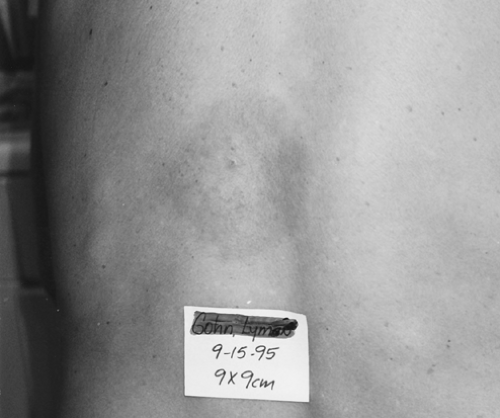

The primary care provider’s role is paramount in the diagnosis and treatment of Lyme disease, as early diagnosis and treatment translate into better outcomes. The best opportunity for an accurate early diagnosis is the characteristic EM or bull’s-eye rash stage (Fig. 16-1; Masters, 1995). The rash, however, may be transient, while the infection can persist and disseminate. Patients may get the rash, make an appointment that is 2 weeks away, and then have the rash fade. Believing they are getting well, patients might cancel the appointment, and an early therapeutic and diagnostic opportunity is missed. The rash is often relatively asymptomatic, and because tick bites on the hands and face are unusual, rarely are they found on a cosmetically sensitive body area. This adds to the lack of awareness by the patient of the seriousness of the condition. If patients with rashes or febrile illnesses after tick bites are not given prompt appointments, preferably within 2 or 3 days, the chances of dissemination, canceled appointments, and missed pathology are all increased.

Researchers and providers are still on the front end of the learning curve for this complicated disease, especially when it is in the late or disseminated phase. Providers can best serve their patients with education, early diagnosis, and effective treatment.

ANATOMY, PHYSIOLOGY, AND PATHOLOGY

Pathology

Lyme disease is transmitted by the bite of a tick infected with the causative spirochete, B. burgdorferi. I. scapularis ticks are the main vectors in North America. The tick itself may be as small as the period at the end of this sentence. Incubation time from tick attachment to disease onset can range from 1 to 31 days, with the average being about 1 week (Luft et al, 1996). The longer the tick is attached, the greater the likelihood of infection. Ticks that are removed within 24 hours are far less likely to transmit disease (Piesman et al, 1987). Just as most tick activity is in the summer, it is no surprise that June and July have the highest infection rates, although some new cases are reported year-round (CDC, 1997).

Lyme disease can usually be divided into three phases:

Early localized: EM rash only, with no other symptoms

Early disseminated: Rash plus evidence of spread (eg, fever, headache, lymphadenopathy)

Late: Infection has spread sufficiently to cause arthritis, carditis, neurologic involvement, or other late manifestations.

As with other spirochetal diseases, such as syphilis, Lyme borreliosis can have early and late phases and protean clinical manifestations that involve several organ systems. The EM rash involves the skin in about 60% of infected patients. A flu-like illness involving nausea and headache can also occur in the early phase. If untreated, or when treatment failure occurs, Lyme borreliosis can result in the spread of the bacteria to various areas of the body, including the skin, joints, eyes, heart, and

the central and peripheral nervous systems. A migratory oligoarthritis is common, with the knee being the most common joint affected. The most prevalent neuropathy is a facial or seventh nerve palsy (Bell’s palsy). Additional complications can include involvement of other peripheral nerves, radiculoneuropathy, lymphocytic meningitis, acute-onset high-grade (second- or third-degree) heart block, atrioventricular conduction defects, and myocarditis. Less common conditions range from myositis to keratitis.

the central and peripheral nervous systems. A migratory oligoarthritis is common, with the knee being the most common joint affected. The most prevalent neuropathy is a facial or seventh nerve palsy (Bell’s palsy). Additional complications can include involvement of other peripheral nerves, radiculoneuropathy, lymphocytic meningitis, acute-onset high-grade (second- or third-degree) heart block, atrioventricular conduction defects, and myocarditis. Less common conditions range from myositis to keratitis.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Most cases of Lyme disease occur in three generally recognized main endemic foci: the northeast, the north-central, and the far western regions. Hundreds of providers, however, in the Midwest and South have reported patients who fulfill both the surveillance and clinical criteria for diagnosis (CDC, 1997; Masters et al, 1998). Spirochetes have been observed in southern and midwestern ticks (Walker et al, 1996; Barbour et al, 1996; Feir et al, 1994). Studies to determine if these spirochetes are related to human clinical Lyme disease are underway. In the meantime, clinical Lyme disease in the South has been termed Lyme disease, Lyme-like disease (Masters & Donnell, 1995), erythema migrans rash disease (Walker et al, 1996), and Masters’ disease (Telford et al, 1997). There is evidence that the clinical differences are negligible because the diagnosis, sequelae, and treatment are similar to those of Lyme disease elsewhere (Masters et al, 1994).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree