(4)

Pain Management Center, Cologne-Hürth, Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany

These plexuses, closely related to one another, are formed by the ventral branches of the lumbar, sacral, and coccygeal spinal nerves (Figs. 59.1, 59.2, 59.3, 59.4, and 59.5).

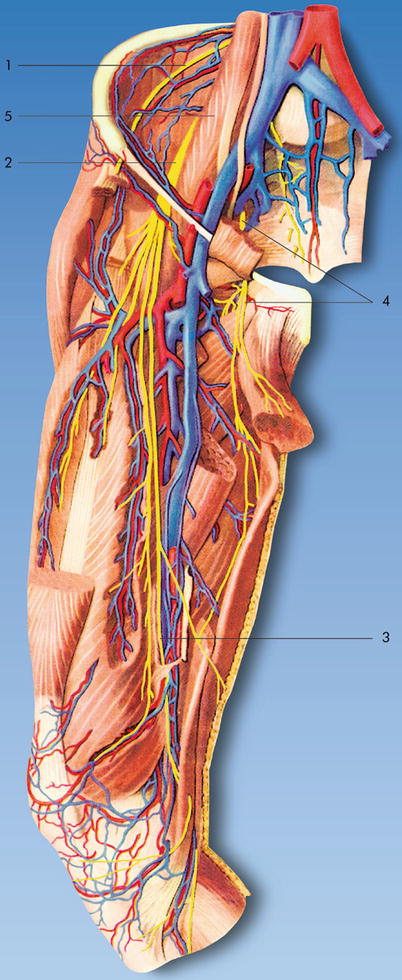

Fig. 59.1

Anatomy: lumbar plexus, sacral plexus, and coccygeal plexus. (1) Lumbar plexus, (2) lumbosacral trunk, (3) sympathetic trunk, (4) sacral plexus, (5) lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, (6) femoral nerve, (7) obturator nerve, (8) iliohypogastric nerve, (9) ilioinguinal nerve, (10) subcostal nerve, (11) quadratus lumborum muscle, (12) psoas major muscle, (13) iliacus muscle, (14) genitofemoral nerve (Reproduced with permission from Danilo Jankovic)

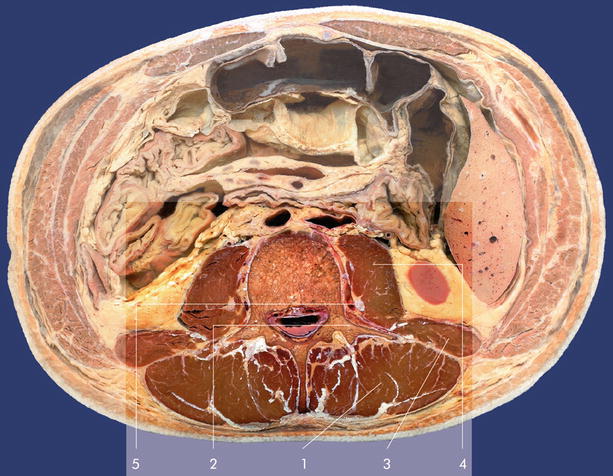

Fig. 59.2

Lumbar plexus. Transversal dissection. (1) Lumbar plexus, (2) os sacrum, (3) intervertebral disc, (4) left external iliac artery, (5) iliopsoas muscle, (6) left external iliac vein (Reproduced with permission from Danilo Jankovic)

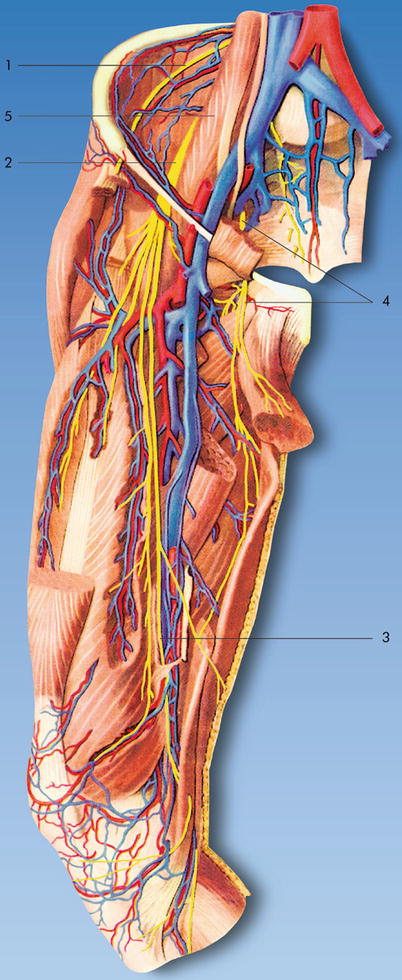

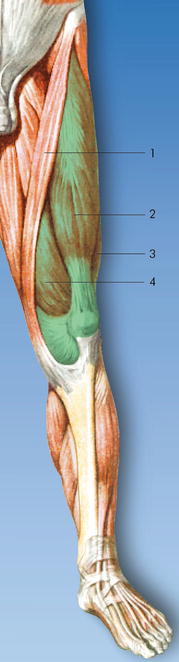

Fig. 59.3

Lumbosacral plexus. Ventral view. (1) Lumbar plexus, (2) lumbosacral trunk, (3) sacral plexus, (4) medial sacral artery: left and right side: sympathetic trunk (Reproduced with permission from Danilo Jankovic)

Fig. 59.4

Lumbosacral plexus. Dorsal view. (1) Lumbar plexus, (2) lumbosacral plexus, (3) sacral plexus (Reproduced with permission from Danilo Jankovic)

Fig. 59.5

Anatomy. Medial sagittal dissection. (1) Lumbosacral plexus, (2) iliopsoas muscle with femoral nerve, (3) obturator nerve (Reproduced with permission from Danilo Jankovic)

The lumbar plexus lies in front of the transverse processes of the lumbar vertebrae. It mainly arises from the ventral branches, the first three lumbar nerves, most of the fourth lumbar nerve, and the twelfth thoracic nerve (subcostal nerve).

The most important branches of the plexus are located in a fascial compartment that is enclosed (“sandwiched”) by the quadratus lumborum, psoas major, and iliacus muscles. The first lumbar nerve, which contains a branch from the twelfth thoracic nerve, divides into an upper branch (iliohypogastric nerve and ilioinguinal nerve) and a lower branch (genitofemoral nerve).

Most of the second, third, and parts of the fourth lumbar nerves form ventral branches, from which the femoral nerve and obturator nerve branch off. The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve is formed from fibers of the ventral branches of L2/L3.

The caudal parts of the ventral branches of L4 and L5 combine to form the lumbosacral trunk. Together with the ventral branches of the first three sacral nerves and the upper part of the ventral branch of the fourth sacral nerve, the lumbosacral trunk forms the sacral plexus, the largest branch of which is the sciatic nerve. The lumbar plexus is also connected with the lumbar part of the sympathetic nervous system via two or three long communicating branches. The thickness of the ventral branches of the lumbar nerves increases markedly from the first to the fifth nerve (L1 has a diameter of ca. 2.5 mm, L2 is already ca. 4 mm, L3 and L4 are ca. 6 mm, and L5 is as large as 7 mm).

The coccygeal plexus arises from the lower part of the ventral branches of the fourth and fifth sacral nerves, as well as the coccygeal nerves.

Lumbar Plexus Blocks

Two techniques are described that belong to the standard methods for blocking the lumbar plexus:

1.

The caudal (ventral) psoas compartment block (“three-in-one” inguinal femoral paravascular block)

2.

The cranial (dorsal) psoas compartment block

Inguinal Femoral Nerve Block (“Three-in-One” Block)

Danilo Jankovic5

(5)

Pain Management Center, Cologne-Hürth, Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany

Introduction

The concept underlying lumbar plexus blocks is that the course of the neural network from the transverse processes to the inguinal ligament lies within a perivascular and perineural space. Like the epidural space, this space limits the spread of the local anesthetic and conducts it to the various nerves.

The initial description of the 3-in-1 block (an infero-anterior approach to the femoral, lateral femoral cutaneous, and obturator nerve) was published by Winnie et al. in 1973 involving a small number of patients. The authors postulated that a block of the entire lumbar plexus can be accomplished by a single perivascular injection slightly distal to the inguinal ligament. Consequently, a single injection should result in anesthesia of the femoral, the lateral femoral cutaneous, and obturator nerves (Figs. 59.6, 59.7, and 59.8). Winnie et al. suggested that the underlying mechanism of this regional anesthetic technique should be a cephalad distribution of the local anesthetic along the fascial layer. Within the connective tissue and neural sheath, the concentration and the volume of the local anesthetic determine the extent of the block’s spread [6–8].

Fig. 59.6

Anatomy: femoral nerve, lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, and obturator nerve. (1) Lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, (2) femoral nerve, (3) saphenous nerve, (4) obturator nerve, (5) psoas major muscle (Reproduced with permission from Danilo Jankovic)

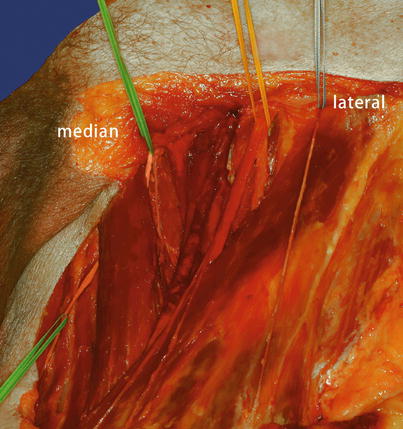

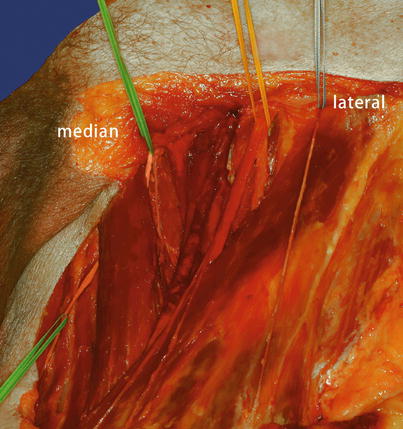

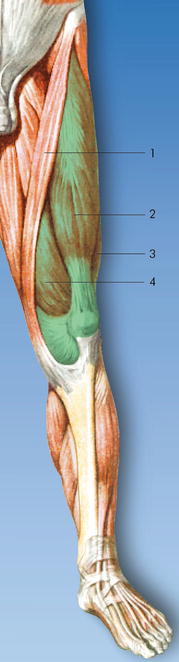

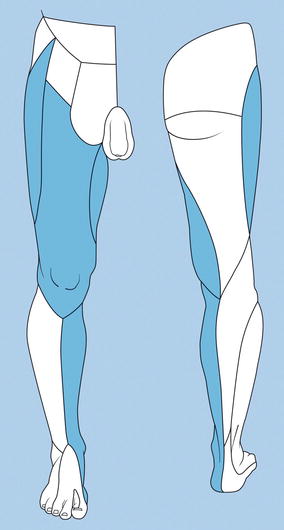

Fig. 59.7

(1) Femoral nerve (yellow), (2) lateral cutaneous femoral nerve (blue), (3) obturator nerve (green). In clinical practice, the obturator nerve (posterior branch) was never been shown to be anesthetized effectively (Reproduced with permission from Danilo Jankovic)

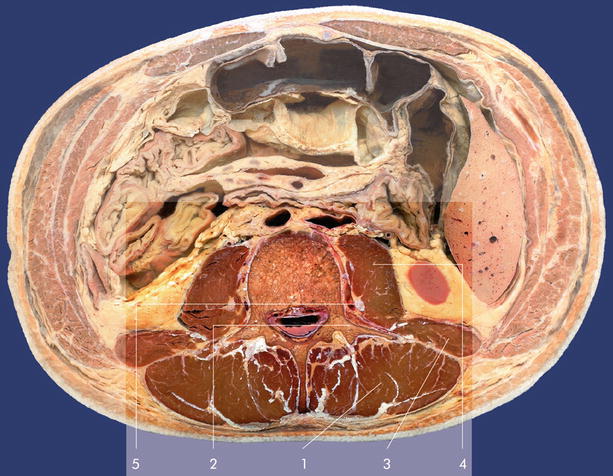

Fig. 59.8

Transversal dissection. (1) Femoral vein, (2) femoral artery, (3) femoral nerve, (4) lateral cutaneous femoral nerve, (5) obturator nerve with vasa obturatoria, (6) sartorius muscle, (7) fascia lata, (8) sciatic nerve, (9) vesica urinaria, (10) rectum (Reproduced with permission from Danilo Jankovic)

This hypothesis, however, was never confirmed clinically. Moreover, an MRI study clarified the spread of local anesthetic after an inguinal injection of local anesthetic lateral to the femoral artery and concluded that the distribution of local anesthetic follows a lateral and slightly medial direction but never a cephalad direction. One of the main proposed advantages of the 3-in-1 block was the ability to achieve block of the obturator nerve using this approach. In clinical practice, however, the obturator nerve (posterior branch) was never been shown to be anesthetized effectively using this approach [9–13]. Capdevila et al. reported that the local anesthetic used in 3-in-1 blocks spreads under the fascia iliaca but rarely to the lumbar plexus. Both techniques resulted in poor blocks of the obturator nerve [14].

Functional Anatomy

The femoral nerve divides slightly distal to the inguinal ligament in several branches, which is the rationale for the nerve block needle to be inserted close to the distal ligament when performing the 3-in-1 block. The femoral nerve supplies motor branches to the quadriceps femoris, sartorius, and pectineus muscles, and its sensory branch (saphenous nerve) innervates the anteromedial side of the lower leg down to the medial ankle. Both the obturator nerve and the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve divide at variable levels from the femoral nerve (Figs. 59.6, 59.7, and 59.8).

The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve arises from the ventral branches of the L2 and L3 spinal nerves, passing lateral to the psoas muscle and then to the iliacus muscle. Covered by the fascia iliaca, it then runs to the region of the anterior superior iliac spine. It passes under the inguinal ligament and under the deep circumflex iliac artery and enters the thigh, where it lies under the superficial sheet of the fascia and divides into a thicker descending branch and a smaller posterior branch, which penetrate the fascia separately. The posterior branch runs posteriorly over the tensor fascia lata muscle and reaches the gluteal region. The anterior branch runs 3–5 cm below the inguinal ligament and then downwards along the anterior surface of the vastus lateralis muscle as far as the lateral knee area, where it sends off lateral branches (Figs. 59.6, 59.7, and 59.8).

The obturator nerve arises from the ventral branches of the L2–L4 spinal nerves.

The trunk runs downwards along the medial edge of the psoas muscle, passing behind the common iliac vessels to reach the pelvis and the obturator canal. Within the canal, it divides into its two end branches—the anterior and posterior branches. It provides the motor supply for the obturator externus muscle and the adductors of the thigh, sends off branches to the hip and knee joints and to the femur, and provides the sensory supply for a highly variable cutaneous area on the inside of the thigh and lower leg (Figs. 59.6, 59.7, and 59.8).

Advantages

1.

Suitable for postoperative or post-traumatic analgesia and for therapeutic blocks

2.

Suitable for patients in whom a unilateral block is desired—particularly in outpatient procedures

Disadvantages

1.

Success is unpredictable.

2.

Larger amounts of local anesthetic are necessary (particularly if the sciatic nerve is also being blocked).

3.

The likelihood of systemic toxicity is increased.

4.

Longer onset times have to be expected (surgical indications).

5.

Despite larger amounts of local anesthetic, not all nerves in the plexus are blocked (e.g., the obturator nerve and lateral femoral cutaneous nerve).

6.

For surgical procedures with ischemia or a tourniquet, neuraxial anesthesia is preferable.

Indications

Surgical [19–22]

1.

Superficial surgical interventions in the innervated area: wound care, skin grafts, and muscle biopsies [17]

2.

Analgesia for positioning for neuraxial block anesthesia in femoral neck fractures

3.

Performing surgical interventions in the area of the lower extremity in ischemia or tourniquet, in combination with sciatic nerve block [15, 16]

Larger volumes of local anesthetic have to be used here (toxicity!).

4.

Outpatient procedures

Therapeutic

1.

Postoperative pain therapy (e.g., after femoral neck, femoral shaft, tibial and patellar fractures, knee joint operations) [18]

2.

Post-traumatic pain

3.

Postoperative neurolysis or nerve reimplantations for better innervation

4.

Early mobilization after hip or knee joint operations

5.

Arterial occlusive disease and poor perfusion in the lower extremities

6.

Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) types I and II

7.

Postamputation pain

8.

Edema in the leg after radiotherapy

9.

Diabetic polyneuropathy

10.

Knee joint arthritis

11.

Elimination of adductor spasm in paraplegic patients

Block Series

A series of six to eight blocks is recommended. When there is evidence of improvement in the symptoms, additional blocks can also be carried out.

Prophylactic

1.

Postoperative analgesia

2.

Prophylaxis against postamputation pain

3.

Prophylaxis against complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS)

Contraindications

Specific

1.

Infections (e.g., osteomyelitis, pyoderma) or malignant diseases in the inguinal region

2.

Local hematoma

3.

Anticoagulant treatment

4.

Distorted anatomy (due to prior surgical interventions or trauma to the inguinal and thigh region)

Relative

The decision should be taken after carefully weighing up the risks and benefits:

1.

Hemorrhagic diathesis

2.

Stable central nervous system disorders

3.

Local nerve injury (when it is difficult to determine whether the cause is surgical or anesthetic)

4.

Contralateral nerve paresis

5.

Patients with a femoral bypass

Procedure

This block should be carried out by experienced anesthetists or under their supervision. Full information for the patient is mandatory.

Preparations

Check that the emergency equipment is complete and in working order. Sterile precautions, intravenous access, ECG monitoring, pulse oximetry, intubation kit, ventilation facilities, emergency medication.

Materials

Fine 26-G needle, 25-mm long, for local anesthesia.

Peripheral nerve stimulator.

Single-Shot Technique

50 (80)-mm-long atraumatic 22-G (15°) short-bevel insulated stimulating needle with injection lead (“immobile needle”).

Continuous Technique*

Peripheral nerve stimulator.

Catheter kit (including a 50-80-mm 18-G (15°)) stimulating needle and catheter 0.45 × 0.85 × 400 mm or Tuohy set: 52 (102)-mm-long 18-G Tuohy needle with catheter.

Syringes: 2 and 20 mL.

Local anesthetics, disinfectant, swabs, compresses, sterile gloves, and drape.

*If technical difficulties arise, the catheter and Tuohy needle must always be removed simultaneously. A catheter must never be removed through the Tuohy needle (as the catheter may shear!).

Patient Positioning

Supine, with the thigh slightly abducted. The patient’s ipsilateral hand lies under the head. The person carrying out the injection must stand on the side being blocked.

Landmarks

1.

The femoral artery is palpated 1–2 cm distal to the inguinal ligament. It is held between the spread index and middle finger. The injection point lies about 1–1.5 cm laterally.

2.

Skin prep, subcutaneous local anesthesia, sterile drapes; draw up local anesthetic into 20-mL syringes, check patency of injection needles and functioning of nerve stimulator, and attach electrodes.

3.

Preliminary puncture with a large needle or stylet.

The quadriceps femoris muscle and the patella must be observed throughout the procedure.

Injection Technique

Single-Injection Technique

1.

The injection is carried out in a cranial direction at an angle of about 30–40° to the skin surface, almost parallel to the course of the femoral artery.

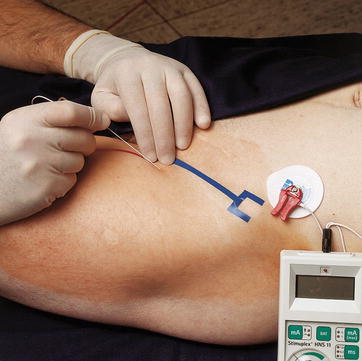

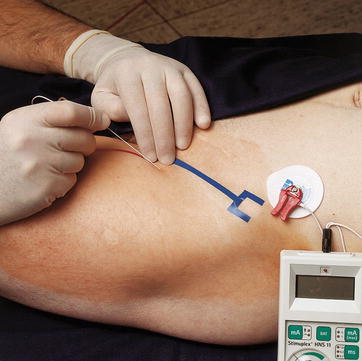

Stimulation current of 1–2 mA at 2 Hz is selected with a stimulus duration of 0.1 ms (Fig. 59.9). Usually, the nerve is at the depth of 12+/−4 mm.

Fig. 59.9

Injection. Cranial direction, at an angle of about 30–40° to the skin surface (Reproduced with permission from Danilo Jankovic)

2.

The needle is advanced until contractions of the quadriceps femoris muscle and patellar movements become visible (“dancing patella”). Contractions of the sartorius muscle alone suggest incorrect positioning and are inadequate (Fig. 59.10).

Fig. 59.10

Note the contractions of the quadriceps femoris muscle and patellar movements. (1) Sartorius muscle, (2) rectus femoris muscle, (3) vastus lateralis muscle, (4) vastus medialis muscle (Reproduced with permission from Danilo Jankovic)

3.

Do not advance the needle further!

The stimulation current is reduced to 0.2–0.3 mA. Slight twitching suggests that the stimulation needle is in the immediate vicinity of the nerve.

4.

Aspiration test.

5.

Test dose of 3 mL local anesthetic (e.g., 1 % prilocaine). During the injection, the twitching slowly disappears.

6.

Incremental injection of a local anesthetic (injection–aspiration after each 3–4 mL).

7.

After the injection, compression massage of the injection area is carried out and then flexing of the thigh for about 1 min (Fig. 59.11).

Fig. 59.11

After the injection: flexing the thigh for about 1 min (Reproduced with permission from Danilo Jankovic)

8.

Careful cardiovascular monitoring.

During the injection, distal compression should be applied with the finger to encourage proximal spread of the local anesthetic.

Distribution of Anesthesia

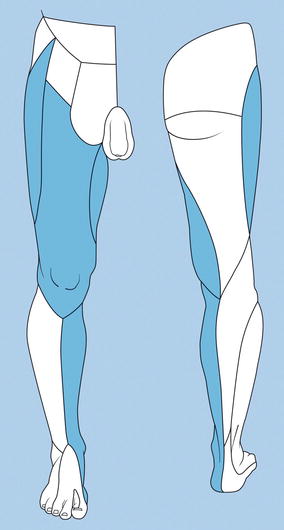

To produce complete anesthesia in the leg, it should be combined with a sciatic nerve block (Figs. 59.12 and 59.13) [15, 16].

Fig. 59.12

The neural areas most frequently blocked after administration of a “three-in-one” block (Reproduced with permission from Danilo Jankovic)

Fig. 59.13

Comparison of the innervation areas of the femoral nerve, lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, and obturator nerve (blue) with the innervation area of the sciatic nerve (red) (Reproduced with permission from Danilo Jankovic)

Continuous Technique

Either nonstimulating (conventional) or stimulating catheters can be used. The site is located in the same way as described for the unilateral technique. The injection is carried out about 2–2.5 cm below the inguinal ligament and 1–1.5 cm lateral to the femoral artery and in a cranial direction at an angle of about 30–40°. Using the Seldinger technique, the catheter is advanced at least 10 cm deep into the fascial compartment. An aspiration test, administration of a test dose, fixation of the catheter, and placement of a bacterial filter then follow. After aspirating again, the local anesthetic is given on an incremental basis.

Dosage

Surgical

1.

15–20 mL—single-injection femoral nerve block

2.

40–50 mL local anesthetic—e.g., 0.5–0.75 % ropivacaine, 0.5 % bupivacaine (0.5 % levobupivacaine), 1 % prilocaine, and 1 % mepivacaine

A combination of local anesthetics with longer-term and medium-term effect has proved particularly valuable for surgical indications—e.g., 1 % prilocaine (20 mL) + 0.5 to 0.75 % ropivacaine (20 mL) or 1 % prilocaine (20 mL) + 0.25 to 0.5 % bupivacaine (0.25–0.5 % levobupivacaine; 20 mL).

Therapeutic

10–15 mL local anesthetic—e.g., 0.2–0.375 % ropivacaine, 0.125–0.25 % bupivacaine (0.125–0.25 % levobupivacaine).

Important Notes for Outpatients

Long-lasting block can occur (even after administration of low-dose local anesthetics—e.g., 0.125 % bupivacaine or 0.2 % ropivacaine). The blocked leg can give way even 10–18 h after the injection. The patient must therefore use walking aids during this period. The same rules apply to the treatment of postamputation pain. During the period of effect of the local anesthetic, the patient should not wear a prosthesis.

A record must be kept of patient information and consent.

Continuous Technique [23, 24]

Test dose: 3–5 mL 1 % prilocaine (1 % mepivacaine).

Bolus administration: 30 mL.

0.5–0.75 % ropivacaine or 0.25–0.5 % bupivacaine.

Maintenance Dose

Intermittent administration.

15–20 mL of local anesthetic every 4–6 h (0.5–0.75 % ropivacaine or 0.25–0.5 % bupivacaine) after a prior test dose.

Reduction of the dose and/or adjustment of the interval, depending on the clinical picture.

Continuous Infusion

Infusion of the local anesthetic via the catheter should be started 30–60 min after the bolus dose. A test dose is obligatory.

Ropivacaine: 0.2–0.375 % | 16–14 mL/h |

1 (max. 37.5 mg/h) | |

Levobupivacaine: 0.125–0.25 % | 18–15 mL/h |

Bupivacaine: 0.125 % | 10–14 mL/h |

Bupivacaine: 0.25 % | 18–10 mL/h |

If necessary, the infusion can be supplemented with bolus doses of 5–10 mL 0.5–0.75 % ropivacaine (0.25–0.5 % bupivacaine or 0.25 % levobupivacaine).

Individual adjustment of the dosage and period of treatment is essential.

Complications

1.

Nerve injuries (see Chap. 5)

Traumatic nerve injury is a rare complication of this technique. It can occur as a result of the use of sharp needles (due to nerve puncture), intraneural or microvascular injury (hematoma and its sequelae), prolonged ischemia, as well as toxic effects of intraneurally injected local anesthetic (see Chap. 5). Probable effects of intraneural injection include a transient neurological deficit (unexpectedly prolonged block, lasting up to 10 days). A suspicion of intraneural needle positioning arises if there is strong twitching even at low levels of stimulation current (e.g., 0.2 mA) and if there is no cessation of the twitching after administration of the test dose. The local anesthetic may also be difficult to inject. Correction of the needle position is essential.

4.

Infection in the injection area (continuous techniques)

5.

Hematoma formation (note the obligatory prophylactic compression)

Psoas Compartment Block (Cheyen Approach)

Danilo Jankovic6

(6)

Pain Management Center, Cologne-Hürth, Germany

The psoas compartment block represents a cranial and dorsal paravertebral access route to the lumbar plexus. The concept is to block the closely juxtaposed branches of the lumbar plexus and parts of the sacral plexus by injecting local anesthetic through a high-access route to the plexus (L4–L5) (see lumbar plexus anatomy). When the quality of the block is good, the area of distribution is comparable with that of the “three-in-one” block (see “3-in-1” femoral nerve block; Figs. 59.12 and 59.13). The most important branches of the plexus are located in a fascial compartment that is enclosed (“sandwiched”) by the quadratus lumborum, psoas major, and iliacus muscles (Figs. 59.14 and 59.15). The following nerves are affected: lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, femoral nerve, genitofemoral nerve, obturator nerve, and parts of the sciatic and posterior femoral cutaneous nerve. A combination of this block with block of the sciatic nerve is necessary to achieve complete anesthesia of the lower extremity.

Fig. 59.14

Anatomy. Transversal dissection on the level of the L3/L4. (1) Erector spinae muscle, (2) transverse process, (3) quadratus lumborum muscle, (4) psoas major muscle, (5) lumbar plexus (Reproduced with permission from Danilo Jankovic)

Fig. 59.15

Lumbosacral plexus. Median sagittal dissection. (1) Lumbosacral plexus at the level of L5–S3 segment, (2) iliopsoas muscle with femoral nerve, (3) obturator nerve (Reproduced with permission from Danilo Jankovic)

Advantages

1.

Better block quality in comparison with the “three-in-one” block.

2.

Suitable for patients in whom a unilateral block is desired, particularly in outpatient procedures.

3.

The method is suitable for postoperative and post-traumatic analgesia and for therapeutic blocks.

Disadvantages

1.

Success of the block is unpredictable.

2.

Larger quantities of local anesthetic are needed (particularly if the sciatic nerve is also being anesthetized).

3.

There is an increased likelihood of systemic toxicity.

Because the placement of the needle is in the deep muscles, the potential for systemic toxicity is greater than it is with more superficial techniques.

4.

The proximity of the lumbar nerve roots to the epidural space also carries risk of the epidural spread of the local anesthetics.

5.

Slower onset must be expected (surgical indications).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree