Fig. 55.1

An anatomic preparation (anterior view) seen from the inside of the pelvis in midsagittal view, showing the muscle attachment inside the sacrum, usually located between the first and fourth anterior sacral foramina. (1) Piriformis muscle, (2) sacrospinous ligament, (3) sacrotuberous ligament, (4) sacrum (Reproduced with permission from Danilo Jankovic)

Fig. 55.2

The piriformis muscle (1) and neighboring muscles, nerves, and vessels: (2) gluteus minimus, (3) gluteus medius, (4) gluteus maximus, (5) quadratus femoris, (6) superior gluteal nerve, (7) inferior gluteal nerve, (8) posterior cutaneous femoral nerve, (9) superior gluteal artery, (10) inferior gluteal artery and vein, (11) internal pudendal artery (Reproduced with permission from Danilo Jankovic)

Fig. 55.3

(a) Posterior view of the piriformis muscle (1) and sciatic nerve (2). (b) High separation of the sciatic nerve (1): the common peroneal nerve courses through the piriformis and the tibial nerve through the infrapiriform foramen, (2) the piriformis muscle with the gluteal inferior nerve, (3) the greater trochanter, (4) quadratus femoris, (5) sacrotuberous ligament, (6) the pudendal nerve in the ischiorectal fossa (Reproduced with permission from Danilo Jankovic)

The function of the PM in the non-weight-bearing limb is lateral rotation of the thigh with the hip extended and abduction when the hip is fixed at 90°. In weight-bearing activities, the piriformis restrains vigorous or excessive medial rotation of the thigh [7, 9, 14, 18]. The other short lateral rotators of the thigh at the hip (the superior gemellus, obturator internus, inferior gemellus, and quadratus femoris muscle), lying distal to the PM, may cause symptoms in PS (especially the obturator internus muscle, which is partly an intrapelvic muscle and partly a hip muscle) [7, 24]. The hamstring muscles may also cause symptoms through activation and perpetuation of trigger points (anatomic attachments of the three hamstring muscles to the ischial tuberosity) [7, 25]. The innervations of PM are usually derived from the first and second sacral nerves. The sciatic nerve arises from the ventral branches of the spinal nerves, from L4 to S3. Exiting from the pelvic cavity at the lower edge of the PM, its trunk measures 16–20 mm in breadth at its origin; runs between the ischial tuberosity and the greater trochanter; turns downward over the gemelli, the obturator internus tendon, and the quadratus femoris muscle, which separate it from the hip joint; and leaves the buttock to enter the thigh beneath the lower border of the gluteus maximus [26]. This is the region where the course of the sciatic nerve is intimately related to the PM and short rotators of the hip. There are six routes by which portions of the sciatic nerve may exit the pelvis, and these are illustrated in Fig. 55.4 [7, 13, 27–30].

Fig. 55.4

The six routes by which portions of the sciatic nerve may exit the pelvis (Reproduced with permission from Philip Peng Educational Series). SN sciatic nerve; PM piriformis muscle

Pathophysiology and Etiology

There are two components that contribute to the clinical presentation: somatic and neuropathic. The somatic component underlying PS is a myofascial pain syndrome caused by contraction of the PM [2, 7, 14, 31, 32]. Piriformis syndrome rarely presents as a single-muscle pain syndrome [7]. Trigger points in the PM are most likely to be associated with trigger points in adjacent synergists, such as the posterior part of the gluteus minimus muscle, the gluteus maximus muscle, three of the lateral rotator group muscles (two gemelli and the obturator internus muscle), the levator ani, and the coccygeus muscles [7, 33, 34]. The neuropathic component refers to the compression or irritation of the sciatic nerve as it courses through the infrapiriform foramen [5, 9, 14, 20, 35–39]. In addition, irritation and compression of the neighboring nerves and vessels (superior gluteal artery, inferior gluteal artery, internal pudendal artery; Figs. 55.2 and 55.5) can give rise to pain, with a classic distribution pattern [7].

Fig. 55.5

(a) The right gluteal area. The gluteal inferior nerve, with the dorsal branches of the posterior femoral cutaneous nerve (1) and the common peroneal nerve (2), courses through the piriformis muscle (4) (intrapiriform foramen), (3) tibial nerve; pir, piriformis muscle; med, gluteus medius; max, gluteus maximus. (b) The right gluteal area. The gluteal inferior nerve (1) courses through the piriformis muscle. The common peroneal nerve (4) runs partly through the intrapiriform foramen, with a small portion passing through the infrapiriform foramen. (c) The left gluteal area. The inferior gluteal nerve (1) courses through the piriform muscle and the infrapiriform foramen. (d) The right gluteal area. The inferior gluteal nerve (1) and common peroneal nerve (4) exit the pelvis through the intrapiriform foramen [61] (Reproduced with permission from Danilo Jankovic)

A number of etiological factors that may account for the presence of PS have been described (Table 55.1) [3–5, 7, 13–15, 18, 20, 23, 33–35, 40–59]. In most patients, there is no identifiable cause.

Previous gluteal trauma can cause sciatica-like pain [23, 35]. This is probably the most common cause of PS [13, 23, 35]. The trauma may be direct (low back or buttocks) [35] or indirect (unusual stretching of the lumbosacral and/or hip muscles through athletic or other strenuous activities), leading to inflammation, spasm, hypertrophy, and eventual contraction of the muscle [13, 23, 35]. Certain anatomic variants, such as double piriformis, and course variants of the sciatic nerve, posterior cutaneous femoral, inferior gluteal nerve, and superior gluteal nerve [4, 5, 7, 14, 15, 30, 40, 41, 60] can predispose to PS through two kinds of entrapment: entrapment between the piriformis muscle and the rim of the greater sciatic foramen and entrapment within the muscle. The first kind of entrapment has been well documented during surgery for the sciatic nerve and other surrounding neurovascular structures (superior gluteal, inferior gluteal, and pudendal nerves and vessels). The second kind of entrapment is depicted in Figs. 55.3b, 55.4, and 55.5, which depends on variations in the way in which the sciatic nerve passes through the piriformis muscle [7, 27, 30, 36, 44, 61].

Some authors have considered that hypertrophy and spasm of the PM [14, 18, 43, 44] is one of the most frequent myotonic reflexes in lumbar osteochondrosis [7, 62]. Previous spine surgery may cause scarring or arachnoiditis around the nerve roots, decrease the excursion of the sacral plexus, and predispose the nerve to a piriformis contraction effect.

Differential Diagnosis

The presence of PS is frequently overlooked; the differential diagnosis is presented in Table 55.2 [3, 4, 7, 9, 14, 18, 41, 45, 51, 62–67].

Table 55.2

Differential diagnosis of the piriformis syndrome

Painful vascular compression syndrome of the sciatic nerve, caused by gluteal varicosities [6] |

Herniated intervertebral disc [67] |

Pseudoradicular S1 syndrome [45] |

Posterior facet syndrome at L4–5 or L5–S1 [63] |

Unrecognized pelvic fractures [14] |

Undiagnosed renal stones [14] |

Clinical Evaluation

Clinical Presentation

Three specific conditions may contribute to PS: myofascial pain referred from trigger points in the PM, nerve and vascular entrapment by the PM at the greater sciatic foramen, and dysfunction of the sacroiliac joint.

Myofascial pain syndrome in the PM is well recognized [7, 20, 33, 34, 50, 64, 68, 69]. Additional pain referred from trigger points in the adjacent members of the lateral rotator group or gluteal muscles may be difficult to distinguish from pain originating in the piriformis trigger points. PS is often characterized by bizarre and initially apparently unconnected symptoms [7, 70]. Gluteal pain is reported to be observed in 97.9 % of cases [71]. Patients report pain (and paresthesias) in the small of the back, groin, perineum, buttocks, hip, back of the thigh (81.9 %) [71], calf (59 %) [71], foot, and also in the rectum (during defecation) and in the area of the coccyx. Low back pain is reported to be observed in 18.1 % of cases [43, 71]. Some authors have suspected that contraction of the PM is an often overlooked cause of coccygodynia [13, 28, 41]. Edwards [72] and Retzlaff et al. [9] have described the syndrome as “neuritis of the branches of the sciatic nerve,” while TePoorten suspected involvement of the peroneal nerve [73]. Swelling in the affected leg and disturbances of sexual function are observed (dyspareunia in women, 13–100 % [74], and disturbances of potency in men are very often present as accompanying symptoms) [4, 7, 74]. When the common peroneal nerve is involved, there may be paresthesia of the posterior surface of the upper leg and some portions of the lower leg supplied by this nerve [23, 45, 75–77]. Dysfunction of the sacroiliac joint has been considered a common and important component of PS [9, 63, 64]. Displacement of the sacroiliac joint may interact with myofascial trigger points in the PM to establish a self-sustaining condition. Sustained tension in the muscle caused by the trigger points may maintain displacement of the joint [63], and the dysfunction induced by the joint displacement apparently perpetuates piriformis trigger points. In this situation, both conditions must be corrected [7].

However, true neurologic findings are not usually present in PS, and sensory deficits may be completely absent [3, 5, 14, 33, 34, 64]. There is no gold standard in diagnosing PS. The physical examination may reveal several of the following well-described signs (Table 55.3) [13, 71]. External palpation of the piriformis line can be used to elicit trigger-point tenderness through a relaxed gluteus maximus muscle. The patient is placed in the Sims position. The line overlies the superior border of the PM and extends from immediately above the greater trochanter to the cephalic border of the greater sciatic foramen at the sacrum [7, 13]. The line is divided into equal thirds. The fully rendered thumb presses on the point of maximum trigger-point tenderness, which is usually found just lateral to the junction of the middle and last thirds of the line. A positive test is reported to be observed in 59–92 % [13, 71, 74] of the patients. The piriformis sign, which presents as tonic external rotation of the affected lower extremity, is reported to be observed in 38.5 % of the patients [13]. The medial end of the PM should be palpated within the pelvis by rectal or vaginal examination (this test is positive in almost 100 % of the patients) [7, 13, 41, 73, 78, 79]. Rectal or pelvic examination may reveal a tender, palpable, sausage-shaped mass along the lateral pelvic wall. Freiberg’s sign involves pain on passive, forced internal rotation of the hip in the supine position, thought to result from passive stretching of the PM and pressure on the sciatic nerve at the sacrospinous ligament (Fig. 55.1) [13, 14, 19, 67]. This test is positive in 56.2 % of the patients (32–63 %) [71, 74]. Pace’s sign [33, 34] consists of pain and weakness on resisted abduction and external rotation of the thigh in a sitting position [13, 33]. A positive test is reported to occur in 46.5 % of the patients (30–74 %) [71, 74]. Lasègue’s sign involves pain on the affected side on voluntary adduction, flexion, and internal rotation [80]. Beatty’s maneuver [1, 37] is an active test that involves elevation of the flexed leg on the painful side while the patient lies on the asymptomatic side. Abducting the thigh to raise the knee off the table elicits deep buttock pain in patients with PS but back and leg pain in those with lumbar disc disease. The Hughes test [81] may be also positive in PS (external isometric rotation of the affected lower extremity following maximal internal rotation). Gluteal atrophy may be present, depending on the duration of the condition. When there is abnormality of the PM, gluteal atrophy may be observed because of the close proximity and involvement of the first and internal rotation second sacral nerves [13, 33, 35, 45]. Examining the patient in the supine position sometimes reveals apparent shortening of the limb on the affected side (this is due to contracture of the piriformis muscle) [7, 45, 73]. In the most severe cases, the patient will be unable to lie or stand comfortably, and changes in position will not relieve the pain. Intense pain will occur when the patient sits or squats (39–95 %) [74]. Sacroiliac tenderness is reported to be observed in 38.5 % of the patients [13]. The buttock on the same side as the PM lesion is sensitive to touch or palpation [9]. Criticism of the use of these signs has focused on the fact that they lack critical evaluation [68].

Table 55.3

Diagnostic maneuvers useful in the evaluation of piriformis syndrome

Maneuver | Sign | Cause of pain | Frequency of positive physical sign | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

n | % | Ref. | |||

Freiberg | Buttock pain | Stretching of the PM | 81 | 56.2 | [71] |

Piriformis line | Buttock pain | Contraction of the PM | 118 | 81.9 | [71] |

24 | 92.3 | [13] | |||

Pace | Buttock pain | Contraction of the PM | 67 | 46.5 | [71] |

Rectal or vaginal examination | Reproduction of sciatic pain | 26 | 100 | [13] | |

Electrophysiological Tests

The role of unprovoked electrophysiological tests (in an anatomical position) is minimal. However, the diagnostic value of such tests can be improved by stressing the muscle in flexion, adduction, and internal rotation (the FAIR test). The test compares posterior tibial and peroneal H reflexes elicited in the anatomic position with H reflexes obtained in flexion, adduction, and internal rotation (normal mean prolongation: 0.01 ± 0.62 ms). A prolongation in the FAIR test of 1.86 ms is an electrophysiological criterion for diagnosing PS [14, 82]. The test correlates well with visual analog scale estimates of pain [14, 15, 19, 71, 83, 84]. Somatosensory evoked cortical potentials are also reported to objectivize sensory abnormalities of innervation [14, 85].

Imaging Modalities

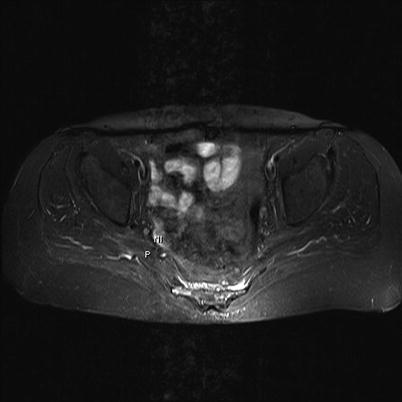

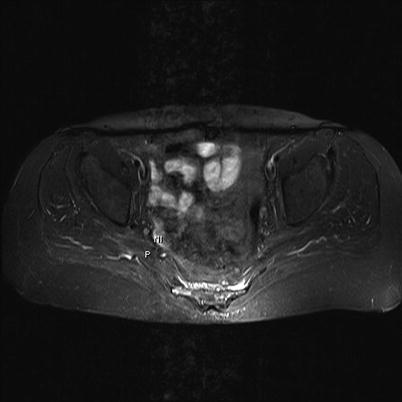

Plain pelvic radiography can only identify calcification of the PM or its tendon in exceptional circumstances [14, 42]. Involvement of the PM in sciatic neuropathy has been supported by evidence from computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 55.6) [62, 68, 86–90], scintigraphy [75], and ultrasound [38, 91]. However, if PS is suspected, a CT examination of the pelvis should certainly be conducted in order to detect side-to-side differences in the PM or other causes of the narrowing of the infrapiriform foramen [30, 92, 93]. If uncertainties remain, an MRI examination of the sciatic nerve and its vicinity—particularly with regard to structural changes in the PM—is indicated [94]. The newly introduced neuroradiological technique of magnetic resonance neurography, alongside established imaging methods such as MRI for evaluating unexplained chronic sciatica, has led to the identification of various changes relating to the piriformis muscle and sciatic nerve which have been further demonstrated with surgical exploration [30].

Fig. 55.6

A normal magnetic resonance image of the piriformis muscle (P) and sciatic nerve (NI) (Reproduced with permission from Danilo Jankovic)

Diagnostic Injection with Local Anesthetics and Steroids

Although piriformis muscle injection has not been compared with other diagnostic tests, it is a widely used method of establishing the diagnosis after initial evaluation [13, 33, 34]. Anesthesiologists are often involved in managing this group of patients, due to their expertise in administering diagnostic and therapeutic blocks. The utility of diagnostic injection is based on anecdotal and expert experience.

Management of Piriformis Syndrome

General

Piriformis syndrome causing sciatica usually responds to conservative treatments, including physical therapy; lifestyle modification; symptomatic relief of muscle and nerve pain with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, tricyclic antidepressants, muscle relaxants, and neuropathic pain agents such as gabapentin, pregabalin, and carbamazepine [95]; and psychotherapy. When patients fail to respond to simple conservative therapy, interventional modalities are considered. In rare circumstances surgical release of the piriformis muscle has been described for difficult cases of PS, but this is occasionally accompanied by morbidity.

Noninvasive Techniques

There is a paucity of controlled trials examining the effectiveness of the management modalities.

Physical Therapy

If etiologically treatable causes of PS have been ruled out, behavioral and physical therapy should be the first step. With regard to physical therapy, relaxation exercises for the pelvic floor muscles, stretching exercises for the gluteal muscles, massage of the PM, and exercises to mobilize the sacroiliac articulation and lumbar spine should be performed [14]. The primary consideration in treating PS with osteopathic manipulation is that the method used must relieve the contracture of the affected musculature and reduce connective-tissue adhesions in the area [9]. Osteopathic physicians use numerous methods of treatment [23, 72], and physical therapy methods are well documented [4, 5, 7, 19–21, 40, 41, 43, 64, 79, 96]. Other recommended techniques include intermittent cold with stretching [7, 34, 79], internal transrectal or transvaginal massage of the muscle [41, 68], ischemic compression with a tennis ball [7, 41], ultrasound application [7, 20], shortwave diathermy in conjunction with a full course of physical therapy [97], self-stretching of the muscle [7], corrective actions (e.g., for lower limb length differences) [7, 20], postural and activity stress reduction, and avoidance of prolonged immobilization of the affected lower limb when driving vehicles for long distances. If a Morton foot structure (mediolateral rocking foot) is present, it should be identified and corrected [7]. In general, physical therapy is performed only as part of multimodal therapy. Criticism of these methods has focused on the lack of critical evaluation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree