INFORMED SURGICAL CONSENT

“Patients should understand the indications for the operation, the risk involved, and the result that it is hoped to attain ”

—ACS Statements on Principles of the College1

A chapter devoted to the topic of informed consent may, at first glance, seem to be out of place in a textbook of acute care surgery. The deliberate, sometimes painstaking, process of informing and getting the consent of patients for surgical procedures hardly seems compatible with the fast-paced decision making required of both the surgeon and the patient when acute conditions arise. Yet, given the higher likelihood of adverse outcomes (death, complications, poor quality of life, etc.) in patients undergoing acute surgical procedures, the importance of the physician and the patient being “on the same page” with respect to the anticipated risks, benefits, and outcome of the planned operative procedure cannot be overestimated. Thus, it behooves all acute care surgeons to have some familiarity with the informed consent process under both elective and nonelective situations. Furthermore, since informed consent regulations may vary from hospital to hospital, and from state to state, some familiarity with these local requirements is desirable as well.

There are perhaps several reasons why the informed consent process might be undervalued by the acute care surgeon:

- Surgeon too busy with multiple simultaneous responsibilities (acute care surgery, trauma, surgical critical care)

- Surgeon’s desire to get the patient to the operating room quickly

- Surgeon’s inability to adequately inform the patient regarding operative procedure since actual operative findings would be unknown to the surgeon at the time of consent

- Urgent/emergent situation precludes development of strong surgeon–patient relationship

- Surgeon under the mistaken belief that informed consent is unnecessary for acute surgical procedures

- Surgeon unsure about validity of consent for acute surgical procedures due to patient factors such as pain, sedation from medications, and anxiety

- Difficulties establishing relationship with acute surgical patients due to language or cultural barriers

This chapter will briefly review the foundation, the principles, and the practice of informed consent as it applies to the elective surgery arena, and will then highlight some important aspects of the consent process that are unique to the nonelective surgical environment. In so doing, some of the above-listed obstacles to achieving true informed consent in acute care surgical patients will be addressed, and some recommendations for perhaps improving the currently existing consent process will be offered.

INFORMED CONSENT IN ELECTIVE SURGICAL PRACTICE

Foundation of Informed Consent

A comprehensive review of the informed consent process is beyond the scope of this chapter, but the interested reader is referred to several excellent recent reviews on the topic.2–7 However, some basic understanding of the history, as well as the components of the process, is necessary in order to place “emergent” informed consent into proper perspective. To begin with, it must be emphasized that informed consent is much more than obtaining a patient’s signature on a consent form. True informed consent is a process wherein the patient is first informed by the surgeon of the risks, benefits, and intended outcomes of the proposed surgical procedure, followed by the patient’s consent to undergo the procedure. Note here that it is the responsibility of the surgeon performing the procedure to both (1) inform the patient and (2) obtain the patient’s consent, and that these responsibilities should not be abdicated to other members of the surgical team. Constraints of time and place occasionally preclude the surgeon from witnessing the patient’s (or patient’s surrogate) written signature on the consent form, especially when the procedure is being done on an emergent or urgent basis. Under these unique circumstances, it is permissible for a resident physician or nurse to obtain the patient’s signature on the consent form, as the form itself is simply a legal document that attests to the fact that the informed consent process has been carried out by the surgeon. Indeed, signing, or even use of, the consent document is not a mandatory feature of the informed consent process from an ethical standpoint, although it may well be a legal requirement of a particular institution or state. All surgeons should therefore familiarize themselves with the requirements of the institutions and states within which they work. The content and structure of consent forms is discussed further elsewhere in this chapter.

Informed consent therefore really represents two separate processes and two separate tasks for the surgeon—inform and consent. In the United States, these two processes, though now inextricably linked, actually developed sequentially, separated by more than 40 years. The concept of simple consent was established first in 1914 in the case of Schloendorff v. The Society of New York Hospital.8 In this case, consent had been obtained from the patient for an examination under ether anesthesia. However, while the patient was under anesthesia, the surgeon, without the patient’s explicit consent, removed an abdominal tumor. Postoperatively the patient developed gangrene of the hand, which she claimed directly resulted from resection of the abdominal mass. The court ruled in favor of the patient, stating “every human being of adult years and sound mind has a right to determine what shall be done with his body; and a surgeon who performs an operation without his patient’s consent, commits an assault for which he is liable in damages.”7 Thus the concept of patient autonomy, a fundamental ethical principle and a fundamental underpinning of informed consent, was upheld by the court. No longer could surgeons unilaterally decide (and carry out) what they felt was in their patient’s best interest—the patient’s consent was first required. However, no further stipulations were made as to the quality of that consent until 1957, when, in Salgo v. Leland Stanford Jr. University Board of Trustees , the courts imposed a further duty on the surgeon to provide the patient with the information necessary to make an “intelligent” consent decision.9 The patient in this case became paraplegic following performance, by his surgeon, of a translumbar aortogram, which involved injection of sodium urokon. This particular complication was a known, but quite rare, risk associated with this agent, one that Mr. Salgo’s surgeon had not discussed with him prior to performing the aortogram. Although the case was ultimately decided in favor of the physician, the court’s opinion made it quite clear that the physician had a responsibility to inform the patient as part of the consent process—“a physician violates his duty to his patient…if he withholds any facts which are necessary to form the basis of an intelligent consent by the patient to the proposed treatment.” Although this new requirement of the physician to provide any necessary facts may seem vague or overly onerous, the same opinion also provided the physician with some room for judgment in informed consent discussions—“In discussing the element of risk a certain amount of discretion must be employed consistent with the full disclosure of facts necessary to an informed consent.”4 The opinion in the Salgo case appears to represent the first documented use of the phrase “informed consent” and clearly ushered in a new era of physician responsibility in obtaining consent for medical treatments. Decades following Salgo , there is still not universal agreement as to how much actual discretion a physician must employ in informed consent discussions. This aspect of the informed consent discussion will be discussed in greater detail below.

Principles of Informed Consent

The process of informed consent requires several fundamental assumptions (10):

- The physician has provided adequate information with which to make a decision (adequate physician disclosure)

- The patient is competent to make a decision (patient competence)

- The patient indicates full understanding of the situation and the information imparted to him by the physician (patient understanding)

- The patient voluntarily consents to the proposed intervention (absence of undue influence)

Adequate Physician Disclosure. What constitutes adequate disclosure by the consenting physician? As discussed above, the Salgo ruling, which established the concept of informed consent more than 50 years ago, required physicians to provide “any facts… necessary <for an> intelligent consent, ” but also allowed for some physician discretion in these discussions. In response to the ambiguity of the Salgo decision, three ethical standards have evolved over the years 2,11

- The Professional Standard (also called the “Reasonable Physician Standard” or the “Professional Community Standard”)—Requires the physician to disclose what a reasonably prudent physician with the same background, training, and experience, and practicing in the same community, would disclose to a patient in the same or similar situation

- The Materiality Standard (also called the “Reasonable Patient Standard” or the “Prudent Patient Standard”—Requires the physician to disclose what a reasonable patient in the same or similar situation would need to know in order to make an appropriate decision.

- The Subjective Patient Standard—Requires the physician to disclose what a particular patient, in his or her own unique set of circumstances and conditions, would need to know in order to make an appropriate decision.

From an ethical perspective, none of these standards is ideal. The Professional Standard has been criticized as being too physician-centered, in that it preferentially values what the physician, not the patient, thinks is important. The Materiality Standard fails to define what a “reasonable” patient is, and the Subjective Standard perhaps makes unreasonable demands of the physician to discern the particular values, interests,and life circumstances of every patient who needs informed consent. From a legal perspective, most states have included language in their informed consent statutes that define which of the three standards described above is recognized in that particular state. The Encyclopedia of Everyday Law, available online, nicely summarizes these requirements for many of the 50 states, and the reader is advised to familiarize himself or herself with the standard currently being used in the particular state in which he or she practices.11

Although states may vary in the type of informed consent standard to which they hold physicians who practice within their borders, there does seem to be general consensus as to the basic elements of a proper informed consent discussion. In fact, several professional health care organizations have adopted formal informed consent standards for their respective organizations. The American College of Surgeons for example, in its Statement on Principles, outlines four specific items that should be included in informed consent discussions. These are

- The nature of the illness and the natural consequences of no treatment

- The nature of the proposed operation, including the estimated risks of mortality and morbidity

- The more common known complications, which should be described and discussed

- Alternative forms of treatment, including nonoperative techniques

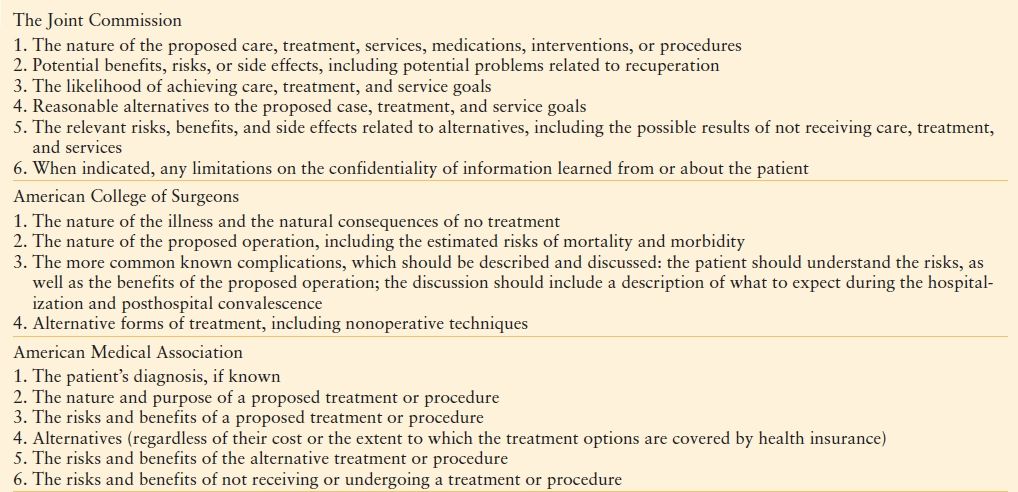

The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations and the American Medical Association have established similar guidelines (Table 60.1). Finally, it is important to note that the health care provider is not obliged to disclose risks that are commonly understood, obvious, or already known to the patient.12

TABLE 60.1

ELEMENTS OF INFORMED CONSENT

From Raper SE, Sarwer DB. Informed consent issues in the conduct of bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4(1): 60–68.

Patient Competence. In actuality, incompetence is a legal condition that can only be determined by the courts. Persons judged by the courts to be incompetent, by definition, are precluded from providing informed consent for themselves or for others. Similarly, minors, with very few exceptions, are legally prohibited from providing informed consent, although ethically, they should be included in informed consent discussions when they possess the maturity to do so.10 Beyond legal considerations, and adult (nonminor) status, patients must possess adequate capacity for medical decision making. Capacity refers to the ability of the patient to process the information received and communicate a meaningful response, and is decision specific, so that a given patient may demonstrate capacity for medical decision making for one aspect of his or her care, yet lack decision-making capacity in other medically related areas.6 Although there is no legal requirement for such, psychiatric consultation is frequently recommended when the loss of decision-making capacity in a given patient is suspected. However, the treating physician may actually be in the best position to assess capacity under these circumstances, since this physician likely has a better understanding of the patient’s medical condition, as well as the risks, benefits, and alternatives to the proposed intervention, and is also in the best position to judge whether the patient’s response to the circumstances is appropriate. Psychiatrists, however, may be helpful in working with the patient to restore capacity for medical decision making, although the time course of this restoration process may not be conducive to decision making in situations of acute surgical illness. In situations where the patient’s decision-making capacity is confirmed to be lacking, or when patients have been deemed incompetent (including minors), and informed consent for a medical intervention is required, consent must be sought from the patient’s surrogate. Most states have legislation that establishes the hierarchy of persons acting as a patient surrogate. Typically, a court-appointed guardian heads the list, followed by a health care power of attorney. In the absence of either of these two individuals, consent would then need to be sought from spouses, adult children, parents, siblings, etc., although the precise order of these individuals in the hierarchy does vary from state to state. Once again, it is a good idea to become familiar with the regulations in force in the state in which one practices. This information can be accessed at http://new.abanet.org/aging/PublicDocuments/famcon_2009.pdf.13

As mentioned above, some exceptions to the “incompetent minor rule” do exist that allow for informed consent to be obtained from minors. Specifically, emancipated minors are legally permitted to provide informed consent for themselves. An emancipated minor is one who has assumed the responsibilities of adulthood, usually by willingly living apart from one’s parents and by managing one’s own financial affairs. Also included within this emancipated minor category are married minors and minors who are members of the armed services of the United States. These individuals are permitted to participate in the informed consent process as well. Also, minors who are parents are permitted to provide informed signature for their children. A final exception, the “mature minor doctrine” can be invoked, enabling a physician to act on the signature of a minor when parental signature cannot be obtained. Under these circumstances, the minor must be at least 15 years old, must appear capable of fully understanding the medical situation, must have received full disclosure of risks, and must grant consent to treatment.6,14

Patient Understanding. Even in situations where the patient’s decision-making capacity is not in question, the patient may still not fully comprehend the nature of the procedure or treatment for which his/her consent is being sought. In addition to providing full disclosure, the surgeon also must ascertain whether the patient has an adequate understanding of the intervention to which he or she is being asked to consent. Several distinct thought processes have been identified in patients consenting to surgery that may interfere with their complete understanding of what their surgeons are telling them.3 Some examples of these include

- A profound belief that surgery will result in cure

- Unrealistic expectations of the surgeon (or the institution) brought about via reputation, or by virtue of being a superspecialist (or a superspecialty hospital)

- Enhancement of physician trust as a result of being referred by family, friends, or other physicians

- Belief in medical expertise as opposed to medical information

- Resignation on the part of the patient to the risks of medical treatment

- Desire on the part of the patient to abrogate decision making to the surgeon (“do whatever you think is best, doc…”)

Each of these attitudes that patients may bring with them to informed consent discussions may prevent the patient from fully engaging in, and thus fully understanding, even the most well-intentioned discussion of risks, benefits, and alternatives. Physicians need to be aware of these potential pitfalls and take the steps necessary to ensure their patient understands the information they have just imparted to them. This can be done by analyzing the types of questions being asked them by the patient, but also by asking probative questions of the patient as a means of identifying areas of incomplete comprehension. It is often helpful for the surgeon to ask patients to reiterate in their own words their understanding of the rationale, risks, and benefits of the procedure.

Absence of Undue Influence. Finally, it is also the responsibility of the surgeon to ensure that the consent obtained from the patient is voluntary and represents what the patient believes is in his or her best interest. Many external influences may exert themselves in the setting of surgical illness, particularly so under the conditions of acute surgical illness. Pain, fear, and anxiety can be powerful motivators of behavior and may propel patients to make decisions that they might not make under less stressful conditions. Steps should be taken to remove as many of these emotional and physiologic barriers to true informed consent as possible, recognizing that the pharmacologic treatment of pain and anxiety may also potentially impair the patient’s capacity for decision making.6 In addition to these external influences, family and friends may occasionally, and possibly quite unintentionally, exert unwanted influence over the consent process. Obvious examples of this can be seen in patients contemplating cosmetic or even bariatric surgery, where perhaps the patient may be considering surgery not for his or her own benefit, but rather to please others.7 Should the surgeon suspect that the patient is experiencing unwanted external influences such as these, a private discussion with the patient (and perhaps a separate private discussion with the “unwanted influences”) provides the best opportunity to understand and implement the plan of action that maximizes the best interests of the patient.2 Recognize, too, that the surgeon may, intentionally or otherwise, act as a coercive force when it comes to informed consent. Many patients are intimidated by the stereotypical strong-willed surgeon, or by the reputation that precedes even the first encounter with a surgeon. Some surgeons may actually express displeasure or dismay when a patient questions or declines the operative plan, thereby unwittingly contributing to the coercive atmosphere, and a less than informed consent situation. A more subtle form of surgeon coercion occurs when the surgeon, uninvited, offers an opinion as to the course of action the patient should choose, and in so doing, makes it more difficult for the patient to choose an alternate path. In general, such offerings should be avoided by the surgeon unless expressly invited by the patient, and even then, the surgeon must be sure to emphasize that a different course of action chosen by the patient will be respected and honored. Another well-recognized form of surgeon coercion is “framing,” a process wherein the surgeon’s word choices can exert unintended influences on the patient’s decision making.2,3 These word choices, intentionally or otherwise, either overemphasize the benefits (e.g., “you’ll feel like a new man”) or minimize the risks (e.g., “bleeding is never a problem with this type of surgery”) of the proposed intervention, and may lead to unrealistic expectations on the part of the patient. Exaggerating the gravity of the patient’s situation, referred to as “crepe hanging,” is a particularly common and unethical form of framing that preoperatively sets falsely low expectations for the postoperative outcome in order to protect the reputation of the surgeon. If the postoperative outcome turns out to be good, the patient’s appreciation of, and gratitude toward, the surgeon is intensified, whereas, in the unlikely event of a bad postoperative outcome, the surgeon escapes “blame,” since a poor outcome has already been predicted. These subtle and not-so-subtle forms of framing are incompatible with the ethical principles of autonomy and beneficence that underlie informed consent, and they should be scrupulously avoided. One additional common practice that may unintentionally interfere with the goal of obtaining the patient’s voluntary consent is that of waiting until the day of surgery to obtain consent. A consent discussion that occurs in the preoperative holding area, without adequate time for a detailed explanation of the risks, benefits, and alternatives, without adequate time for questions, without adequate time to read the informed consent document, and all perhaps performed after the patient has been administered a preoperative sedative can hardly be considered “informed.” In addition, the patient’s awareness that the operating room has been reserved, that the surgeon has blocked out the time on his or her operating schedule, and that family or friends have taken time off from work to accompany the patient, are all potentially coercive forces that may, perhaps subconsciously, influence a patient to sign a consent document for a procedure to which he is not entirely committed to undergoing. Whenever possible, the informed consent process should be initiated well in advance of the intended procedure, with the patient being given ample time to consider, or even change, their decision. Unfortunately, this luxury of time, which works well for the informed consent process in elective surgery, is not feasible for patients needing to undergo urgent or emergent surgical procedures.

Exceptions to Informed Consent

“If a surgeon is confronted with an emergency which endangers the life and health of the patient, it is his duty to do that which the occasion demands within the usual and customary practice among physicians and surgeons in the same or similar localities, without the consent of the patient.”15

Under some conditions, informed consent may be neither possible nor necessary, and some of these conditions are particularly germane to patients with acute surgical conditions. Occasionally, treatment of a patient without his or her consent can be mandated by law if there is a perceived risk to public health and safety. However, most exceptions to informed consent benefit the patient directly by ensuring timely access to needed medical care for that individual patient. Informed consent can legitimately be waived under the following circumstances11,12,16:

- Medical emergencies

- Unanticipated conditions during surgery

- Patient waiver of consent

- The therapeutic privilege

Medical Emergencies. Medical emergencies constitute the largest category of exceptions to the informed consent requirement, but this well-recognized exception should not be invoked indiscriminately simply because the patient requires “acute” surgical intervention.16 The guiding principle here is whether delay in treatment required to obtain consent would result in harm to the patient. Harm in this context is not necessarily limited to loss of life or limb, but refers to any major adverse outcome that may occur as a result of a delay in treatment. In general, the fact that the patient has presented to the health care facility is taken as evidence of presumed consent to emergency treatment. Frequently, these patients display impaired decision-making capacity due to alterations in mental status brought on by hemodynamic instability, sepsis, or direct Central Nervous System (CNS) insult or injury. Resuscitation, including intubation and mechanical ventilation, can, and should, be undertaken immediately in this patient population without concern for obtaining informed consent based upon the fact that these patients are inherently incompetent, and based upon the assumption that most reasonable individuals under the same circumstances would desire treatment. Of course, when an appropriate patient surrogate is identified, informed consent should be obtained for all subsequent procedures. This approach can also be extended to the perhaps less straightforward situation of the emergency surgery patient with impaired decision-making capacity due to intoxication, but documentation of the patient’s lack of capacity is critical if suspension of the patient’s informed consent rights is to be upheld. This principle is illustrated in Miller v Rhode Island Hospital , where an intoxicated trauma patient was subjected to a diagnostic peritoneal lavage procedure against his will, and sued the hospital for battery. In siding with the defendants, the court held that the determination of whether a patient’s intoxication would render the patient incapable of giving informed consent would depend upon the circumstances, and that medical competency (whether the patient was able to reasonably understand the medical condition, and the risks and benefits of, and alternatives to, the proposed procedure) was the relevant standard for physicians to judge conscious patients in these circumstances.17 Thus, in order for a physician to deny a patient his or her informed consent rights on the basis of intoxication, the physician must first be absolutely convinced that intoxication has rendered the patient medically incompetent, since this is the standard required by the courts to successfully defend a charge of battery. One additional facet of the emergency exemption to informed consent that deserves mention is the issue of consent for blood transfusion. Here again, the issue of medical competency comes into play, since transfusing a medically competent patient against his or her will would clearly constitute battery. Patients deemed medically incompetent, whether due to injury, illness, or intoxication, can be transfused without their consent, even against the objections of the patient or patient’s family under the compelling state interest standard.18 The emergency exemption to informed consent also extends to the “incompetent” minor, such that the informed consent requirement can be waived when an emergency exists and immediate injury or death could result from the delay associated with attempting to obtain parental consent.16 Emergent blood transfusion, without consent, for a minor patient has generally been upheld by the courts, even when the transfusion has been adamantly refused by the parents and the patient, again based upon the compelling state interest in preserving the life of a child. As stated in Novak v Cobb County-Kennestone Hospital Authority , “not even a parent has unbridled discretion to exercise their religious beliefs when the state’s interest in preserving the health of the children within its borders weighs in the balance.”19 In all circumstances where the emergency exception is invoked, it is prudent to document in the patient record the nature of the emergency, and the rationale for proceeding without informed consent. If possible, a corroborating statement in the patient record from a second health care provider is also desirable.14

Unanticipated Conditions During Surgery. The courts have generally looked favorably on surgeons who have performed, on patients under general anesthesia, procedures for which they did not have explicit informed consent as long as (1) the procedure appeared to be in the patient’s best interests and (2) there was not adequate opportunity for the surgeon to obtain consent. This is referred to as the “extension doctrine,” and it assumes that the surgeon is using reasonable judgment. In order to meet the criteria for the extension doctrine, the condition must be one that was unforeseen, and the patient must not have expressly refused such an intervention.12 These circumstances present themselves relatively frequently to the acute care surgeon when undertaking laparotomy for “peritonitis” of unknown origin. In Barnett v Bacharach , a patient who was thought to have an ectopic pregnancy consented only for the removal of the ectopic pregnancy itself. At laparotomy, however, the patient was found to have acute appendicitis and an appendectomy was performed. Following an uneventful recovery, the patient refused to pay for the surgical services provided because informed consent was not first obtained and thus the procedure was unauthorized. At trial, the court found that the surgeon acted properly because of the seriousness of the patient’s condition.20 However, in Tabor v Scobee , the court found that the surgeon had acted improperly when he removed the infected fallopian tubes from a patient who had given informed consent only for an appendectomy. Here the surgeon argued that serious harm or death could have resulted had the procedure been delayed for weeks or months, but this time frame did not fulfill the court’s definition of a condition severe enough to warrant denial of the patient’s informed consent rights.21 Perhaps the patient’s resulting sterility also played a role in the court’s decision.

Patient Waiver of Consent Occasionally, a patient will relinquish his or her right to informed consent by expressly waiving this right and specifically directing the physician to do what the physician thinks is in the patient’s best interest.This is a relatively unusual occurrence in this day and age, and this acquiescence on the part of the patient should be clearly documented by the surgeon in the patient record.

The Therapeutic Privilege. By law, a physician has no obligation to provide informed consent if he or she believes that the patients’ emotional and physical condition could be adversely affected by full disclosure of the treatment risks.22 This is referred to as the therapeutic privilege and, although a legitimate exception, must be invoked with great caution, and with abundant physician documentation in the patient record.

Problems with Informed Consent

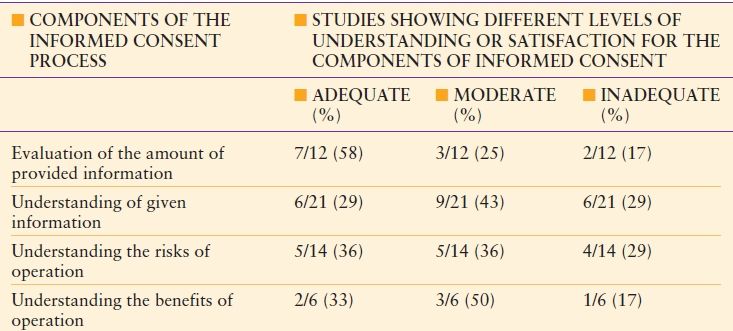

Even in elective surgery situations, and even with the most well-intentioned physician, the informed consent process is far from perfect. Patients seem to comprehend little about what has been explained to them, and what little they understand, they fail to retain for any substantial period of time. Falgas recently conducted a review of 23 articles that assessed the quality of the informed consent process across a variety of surgical specialties. Several different consent discussion formats were represented in these 23 articles, including verbal explanations alone, written materials alone, use of audiovisual media, and various combinations of these formats. Patient understanding was judged as either adequate (more than 80% of the participants in the study had a level of understanding graded in the highest classification category), moderate (50%–80% of the participants in the study had a level of understanding graded in the highest classification category) or inadequate (<50% of the participants in the study had a level of understanding graded in the highest classification category). Based upon these definitions, “adequate” overall understanding of the information provided was demonstrated in only 29% of the patients examined, while only 36% of the patients demonstrated “adequate” understanding of the risks associated with surgery (Table 60.2). Although one may quibble with the definitions used in this review, it is nevertheless quite clear that, regardless of how the informed consent discussion is carried out (verbal, written, with or without audiovisuals), a substantial gap exists between the information that surgeons think they transmit to their patients, and the information that patients actually understand and retain.23

TABLE 60.2

SYNTHESIS OF DATA FROM DIFFERENT STUDIES REGARDING THE EVALUATION OF THE VARIOUS COMPONENTS OF THE INFORMED CONSENT PROCESS FOR SURGERY OR PARTICIPATION IN CLINICAL TRIALS

From Falagas ME, Korbila IP, Giannopoulou KP, Kondilis BK, Peppas G. Informed consent: how much and what do patients understand? Am J Surg. 2009;198(3): 420–435.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree