Fires and Explosions

Jan Ehrenwerth

Harry A. Seifert

CASE SUMMARY 1

A 3-year-old, 28-kg girl child is having recurrent vocal cord polyps removed. The patient is a normal, 3-year-old child with no other serious medical problems. She is taking no medications and is not allergic to any. Previous surgery included the same procedure performed 6 and 12 months ago. The parents have noted that the child tires easily and seems to have difficulty breathing with vigorous activities. This has been getting progressively worse over the last 2 months.

The surgeon is planning to excise the polyps using a carbon dioxide (CO2) laser. The patient is induced uneventfully with sevoflurane and oxygen. Following induction, an intravenous line is started, and rocuronium is used to facilitate intubation. Intubation is accomplished with a no. 4.0 polyvinyl chloride (PVC) uncuffed, endotracheal tube (ETT). A leak around the ETT is noted at 15 cm of water. Anesthesia is maintained with 70% nitrous oxide, 30% oxygen, and 1 MAC of sevoflurane.

The surgeon then proceeds to laser the polyps for approximately 15 minutes. At this time, the scrub nurse notes smoke coming from the operative site. Subsequently, flames appeared from the patient’s mouth, and the ETT was noted to be burning. The scrub nurse quickly extinguishes the flames with a basin of saline and, at the same time, the anesthesiologist disconnects the circuit from the anesthesia machine. The ETT is removed and replaced with a new one. A bronchoscopy is performed which shows severe burns to the tracheobronchial tree and charring of the lungs. The child is taken to the intensive care unit.

What Could Have Been Done to Prevent This Type of Fire?

An operating room (OR) fire can be a serious and devastating complication of airway surgery. A fire can occur with little or no warning and, given the right circumstances, can produce a tremendous amount of heat. It is incumbent upon the surgeon and the anesthesiologist to be aware of the fire risks whenever a laser or electrosurgery unit is being used in the upper airway.1,2

OR fires have been a danger virtually since the advent of inhalation anesthetic agents. Explosive anesthetic agents such as ether and cyclopropane were used for many years. This meant that OR personnel had to be keenly aware of the risk of fires, as well as severely restricting the use of heat-generating devices such as the electrosurgical unit (ESU). With the elimination of the use of explosive anesthetic agents in this country, there has been a decrease in the understanding of the persistent potential for OR fires. Notably, the risk now is probably almost as great as when explosive anesthetic agents were in common use.3,4,5

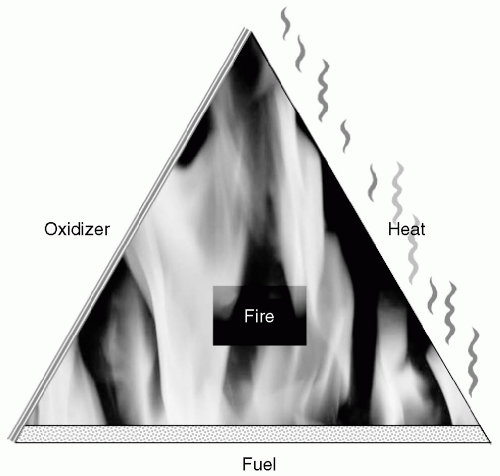

What Is the Fire Triangle?

For a fire to start, three factors have to come together at the same time. This is commonly referred to as the fire triangle (see Fig. 54.1). The three elements consist of an oxidizer, a fuel source, and a means of ignition. An oxidizer is something that supports combustion. In the example presented, both oxygen and nitrous oxide are oxidizers. Therefore, giving the patient 30% oxygen and 70% nitrous oxide is, in its potential to support combustion, equivalent to administering 100% oxygen. The fuel is any flammable material in the immediate area. The list of potential fuels is extensive, but in this case would include the ETT, cotton pledgets, gauze material in the airway, an oral or nasal airway, the patient’s hair, and, if present, the OR drapes. The presence of a high concentration of oxidizer greatly enhances the ability of any fuel to be set on fire. The ignition source can be any device that generates heat. This would include the laser, the ESU and even the ends of fiberoptic light cables.

The best way to prevent a fire is to make sure that one limb of the fire triangle is always isolated from the other two. This will depend on the type of surgery and anesthesia

that is being used, but usually the anesthesiologist can minimize the amount of oxidizer being delivered to the patient, and the surgeon can be careful to not allow a heated instrument or spark to come close to flammable material.6

that is being used, but usually the anesthesiologist can minimize the amount of oxidizer being delivered to the patient, and the surgeon can be careful to not allow a heated instrument or spark to come close to flammable material.6

FIGURE 54.1 Fire Triangle: For a fire to start, three factors have to come together at the same time—an oxidizer, a fuel source, and a means of ignition. |

In the case presented, there were a number of things that could have been done to decrease the risk of a fire. First of all, the anesthesiologists should minimize the amount of oxidizer that is being delivered to the patient. In this case, 30% oxygen and 70% nitrous oxide are the functional oxidizer equivalent of 100% oxygen. The anesthesiologist should decrease the inspired oxygen content by diluting the oxygen with air. By using a pulse oximeter, the FIO2 can be safely titrated down to as low a value as the patient will tolerate. An FIO2 <0.3 is thought to provide increased safety.7 Generally, in a healthy individual, an FIO2 of <30% is sufficient to maintain adequate oxygenation. The use of a PVC ETT is contraindicated in this type of surgery. The PVC will readily burn if accidentally struck by the laser. In addition, because the tube had no cuff, the anesthetic gas mixture being delivered to the patient would readily come back around the ETT and into the operative field. This would further increase the likelihood of starting a fire. An ETT should be selected that is resistant to being ignited or perforated by the laser. The tube chosen must also be specifically resistant to the type of laser that is being used by the surgeon. When the CO2 laser is used, the Laser-Flex (Mallinckrodt, Pleasanton, CA) has been shown to be resistant to the CO2 laser. However, if the surgeon is using the Nd-YAG laser, then this tube is not appropriate. In that case, the Lasertubus (Rusch Inc., Duluth, GA) is a reasonable choice. Both of these tubes come with a double cuff design, and both cuffs should ideally be inflated with normal saline that has been colored with methylene blue.8,9,10 In pediatric patients, cuffed ETTs are not routinely used. However, if one is careful, a small-cuffed tube can be used in most children. If an uncuffed tube is used, then the surgeon should, if at all possible, pack the area around the tube with cotton pledgets soaked in saline. This will limit anesthesia gases from getting into the field. The surgeon must be extremely careful to make sure the pledgets stay moistened, as they can be easily set on fire if they are allowed to dry out.

One problem is that very small, laser-resistant ETTs do not exist for pediatric cases. In the past, anesthesiologists have occasionally wrapped PVC tubes with a metal foil. This should be avoided if at all possible, as the tube can become kinked, the tape can develop gaps, or the wrong type of tape can be used. Alternatively, an anesthetic technique using a metal jet injector, or one whereby the ETT is intermittently removed while the surgeon is lasering and then replaced, can be considered.

In the event that a fire does occur, the anesthesiologist should immediately disconnect the circuit from the ETT, while the surgeon simultaneously removes the ETT. The anesthesiologist can eliminate the oxidizer by disconnecting the circuit at the Y-piece or removing the hoses from the anesthesia machine. In addition to removing the ETT, the surgeon can flood the area with a basin of water or saline that should always be immediately available on the sterile field. Once the fire is out, the patient can be reintubated and the airway inspected with a bronchoscope to assess the degree of injury and remove any foreign material. A bronchoscopy should then be performed to assess the damage and remove any pieces of foreign material. The patient can then be stabilized and taken to the intensive care unit. Fires of this nature almost always result in severe injury to the patient.

KEY POINTS

Preventing a fire is always preferable to treating one.

Isolation of the components of the fire triangle is essential to prevent a fire.

When using the laser or electrocautery in airway surgery, it is important to be aware of all the potential ways that a fire can start.

Whenever possible, the clinician should use an ETT that is specifically resistant to the laser that the surgeon is using.

Minimize the inspired oxygen concentration to <30% whenever possible and avoid nitrous oxide.

CASE SUMMARY 2

A 72-year-old woman is scheduled to have a skin cancer removed from her right cheek. The patient has been in good health and has a history of hypertension and chronic obstructive lung disease. The hypertension is well controlled with a β-blocker and

diuretic. The patient’s lung disease is secondary to a 35 pack-year smoking history. The patient has had no problems with previous surgeries, her laboratory values are within normal limits, and examination of the heart and lungs is normal. The patient is brought to the OR where standard monitors are applied. Her oxygen saturation is 97% on room air. The patient is sedated with a combination of midazolam and fentanyl. The patient is also given, 4 L per minute of oxygen through a nasal cannula. The oxygen tubing is attached to an auxiliary oxygen flow meter on the anesthesia machine.

diuretic. The patient’s lung disease is secondary to a 35 pack-year smoking history. The patient has had no problems with previous surgeries, her laboratory values are within normal limits, and examination of the heart and lungs is normal. The patient is brought to the OR where standard monitors are applied. Her oxygen saturation is 97% on room air. The patient is sedated with a combination of midazolam and fentanyl. The patient is also given, 4 L per minute of oxygen through a nasal cannula. The oxygen tubing is attached to an auxiliary oxygen flow meter on the anesthesia machine.

The patient’s skin is prepped with DuraPrep (3M Health Care, St. Paul, MN). The surgeon places drapes over the patient and the surgical nurse attaches the electrocautery pencil to the ESU machine. Following the skin incision, the surgeon attempts to coagulate some bleeding blood vessels. Immediately, smoke is seen arising from the area of the patient’s shoulder which, within 2 to 3 seconds, turns into a visible fire that engulfs the patient’s head and neck and the drapes. The surgeon douses the flames with a basin of water and the anesthesiologist disconnects the patient from the oxygen supply.

The drapes are subsequently removed and thrown on the floor, and the patient is noted to have second and third degree burns of the face, neck and shoulder. The patient is anesthetized with a general anesthetic, and the burns are debrided and dressed. The patient is then transferred to the intensive care unit for subsequent therapy and monitoring.

Could This Fire during a Monitored Anesthesia Care Sedation Have Been Prevented?

Fires during head and neck surgery, particularly under a MAC type anesthetic, are probably the ones that most frequently occur today. In the case scenario presented in the preceding text, it can be seen that the three legs of the fire triangle were once again allowed to come together. At the end of the case, the surgeon commented that he had literally done dozens and dozens of these procedures in exactly the same way and never had a problem. This is not at all an unusual statement. Frequently, the procedure will be done in exactly the same way numerous times without incident. However, if all parts of the fire triangle (Fig. 54.1) come together at just the wrong time, then a fire will occur.11,12,13,14

There are a number of steps that should have been taken to prevent this fire. The patient’s skin was prepared with DuraPrep solution (3M Health Care, St. Paul, MN). This solution contains 74% isopropyl alcohol. If it is not given approximately 3 to 4 minutes to thoroughly dry, then alcohol vapors will continue to escape from the operative site. These vapors can easily be set on fire by an ESU or a laser. Also, if the person prepping the patient is sloppy, the prep solution can pool around the patient. These pools of solution will take longer to evaporate and continue to give off alcohol vapors for many minutes.

The patient was given 100% oxygen through a nasal cannula, and although the patient’s alveolar inspired oxygen is <30% (at 2 L per minute flow through the cannula), 100% oxygen is flowing very close to the operative site. This, combined with the alcohol vapors, greatly increased the likelihood of a fire occurring when the surgeon activated the ESU. Because the patient’s preoperative oxygen saturation was 97% on room air, depending on the level of sedation, the patient likely did not need any supplemental oxygen. The level of oxygen supplementation can easily be titrated by using the pulse oximeter. Variable levels of oxygen can be attained by using the anesthesia machine to mix room air with oxygen and thereby deliver any desired fraction of inspired oxygen. One way to do this is with an ETT connector from a no. 4.5 ETT inserted into the Y-piece of the anesthesia circuit. The end of the nasal cannula can then be attached to the small ETT connector. Also, if the auxiliary oxygen flow meter has a removable nipple connector, a humidifier with an adjustable oxygen concentration device can be attached. These devices typically can deliver between 28% and 90% inspired oxygen. Decreasing the FIO2 that is delivered to the patient and the operative site (preferably to <30%) will significantly reduce the risk of a fire.7

Whenever the surgeon is operating in the head and neck region during a MAC case, it is extremely important for the surgeon and the anesthesiologist to communicate regarding the exact concentration of oxygen that is being delivered to the patient, by whatever device is in use, and the proximity to the surgical site. The surgeon should plan on draping the patient in a manner that will not allow oxygen to accumulate under the drapes in proximity to where he/she will be using an ESU or laser. The other possibility is for the anesthesiologist to turn off the oxygen and flood the area with room air, or scavenge with a suction device under the drapes before the surgeon uses the ESU or the laser. Depending on how the patient is draped, it may require several minutes before accumulated oxygen can be washed out. Supplemental oxygen will need to be discontinued until the surgeon is finished using the ESU or laser.

This case demonstrates just how rapidly this type of fire can spread. Within a few seconds, the patient and surrounding drapes became engulfed in flames. The first step is to disconnect the oxygen supply from the patient. It is essential that a basin of sterile water or saline be immediately available on the sterile field. This can be used to douse the flames. There is no time to obtain a fire extinguisher. The drapes should be immediately removed and thrown on the floor. If they are still on fire, the fire extinguisher can then be used on the burning drapes.

KEY POINTS

Alcohol-based prep solutions must be allowed to thoroughly dry.

Do not allow oxygen to accumulate around the surgical site.

Institute a method to deliver an FIO2 of < 100% oxygen exiting from the nasal cannula or mask whenever feasible. Ideally this should be <30%.

Titrate to the minimum necessary oxygen concentration using the pulse oximeter (the SpO2 does not need to be 100%).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree