VIDEO 40-1

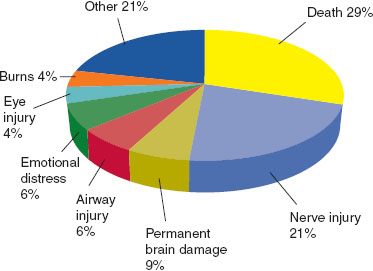

Rates of Selected Anesthetic Complications

The estimated anesthesia-specific mortality risk has steadily declined from approximately 1 in 1,000 in the 1940s to 1 in 10,000 in the 1970s to 1 in 100,000 in the 2000s.

The risk of anesthesia-related morbidity is also difficult to quantify because such data are similarly subject to limitations in reporting and disclosure. It is estimated that more than 1 in 10 patients will have an intraoperative incident and 1 in 1,000 will suffer an actual injury such as a dental damage, an inadvertent dural puncture, peripheral nerve injury, or significant pain (2). Some morbidity, such as venous thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, or catheter-related bloodstream infections, can be predicted and managed. Some morbidity, such as aspiration, previously unknown allergies, nerve injuries, or retained awareness, might be mitigated. However, some morbidity such as stroke can neither be well predicted nor consistently mitigated (Fig. 40-1).

FIGURE 40-1 Most common injuries leading to anesthesia malpractice claims 2000 to 2009. Other category includes aspiration (4%), pneumothorax (3%), back pain (3%), myocardial infarction (3%), newborn injury (2%), headache (2%), and awareness/recall during general anesthesia (2%). Damage to teeth and dentures excluded. American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Closed Claims Project (n–9,214). (From: Posner KL, Adeogba S, Domino K. Anesthesia risk, quality improvement, and liability. In: Barash PG, Cullen BF, Stoelting RK, et al. Clinical Anesthesia, 7th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2013:100.)

II. Risk Management and Patient Safety

A. Ethics

The term ethics is derived from the Greek ethos, translated as “custom” or “habit,” and is a branch of philosophy dedicated to the study of values and customs of groups. In its contemporary applications, ethics relates to the analysis and application of precepts such as right and wrong, good and evil, and norms for interactions between people. Because it is inevitable that disagreements will arise when individual preferences form the basis for health care and end-of-life decisions, ethics provides a framework within which clinicians reconcile differing beliefs and values. Thus, ethics is an open-minded structural framework that facilitates discourse and problem solving in highly complex clinical dilemmas for which there are no clear-cut answers and for which decisions are frequently subject to retrospective scrutiny.

Medical ethics refers to the systematic study of ethical or moral values as they apply to the practice of medicine. Medical ethics addresses issues such as do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders, medical futility, withdrawal of life support, terminal sedation, research subject protections, placebo therapy, access to health care, and the meaning of brain death. However, because ethics is a branch of philosophy, it is as important to understand that it is as much about discourse—structured argumentation representing disparate points of view—as it is about a study of values and customs. Ethics provides the theoretical foundation, structure, and context with which health care providers can have meaningful discussions with patients, families, and among one another regarding deeply personal topics.

Although ethics is widely believed to represent a branch of legal doctrine, it applies equally to all professions. Nonetheless, laws apply to interactions between individuals and between individuals and society. Lawyers are trained to manage opposing points of view and are trained to develop arguments on behalf of their clients. In the United States, laws are derived from the shared ethical and moral principles inherent in the US Constitution. Laws, much like ethical concepts, form the structure and context within which lawyers argue the merits of their clients’ cases. The important relationship of professions with society suggests that professional values must be congruent with the societal values in which the professionals practice. Ethical decisions made in the medical context are subject to public review and must be as unbiased, carefully reasoned, well documented, and as transparent as possible.

The goal of communication in medicine is the formation of a therapeutic alliance that facilitates shared decision making. Many so-called ethical conflicts in clinical practice can be traced to a lack of effective communication. Medical malpractice litigation is very closely linked to the perceptions of patients and families regarding honest communication, team cohesiveness, disclosure of adverse events, and, therefore, their subjective impressions regarding the quality of care. Litigation is more likely to result when there is a significant discrepancy between a patient’s or family’s expectations and perceptions regarding the care that was rendered. In the absence of true medical negligence, patients and families are most likely to remember the respect, caring, and attentiveness (ethical behavior) they encountered during the time of the patient’s health care encounter.

Ethical codes or codes of conduct are largely a set of aspirational values, which are the ethical guiding principles for professions, and apply equally to each and every member of the health care team. The Oath of Hippocrates, the Nightingale Pledge, Thomas Percival’s Code of Medical Ethics, the Oath of Maimonides, the Declaration of Geneva, and the American Medical Association’s Principles of Medical Ethics represent such foundational professional documents. The four formal principles of medical ethics—beneficence, nonmaleficence, autonomy, and justice—represent a set of precepts that must be considered in any discussion of medical ethics, and commonly apply to medical ethics decision making.

The principle of beneficence represents that each health care practitioner should knowingly strive to always act in the best interests of each individual patient (salus aegroti suprema lex). Thus, health care decisions should reflect the highest level of care for each patient, without regard to personal gain, societal interests, or the interests of family.

The principle of nonmaleficence is embodied in the concept of primum non nocere—“first, do no harm.” Harm may be variably interpreted and includes either willful omission or commission of an act that inflicts emotional or psychologic distress, pain and suffering, or physical injury. Nonmaleficence is also inherent in the fiduciary duty (i.e., acting in the patient’s best interests) that physicians owe to their patients. Nonmaleficence can become legally operative with medical interventions that have risks that cannot be eliminated no matter how much care and attention is rendered. Where a therapeutic intervention is prescribed with the intent of “doing good” and an unavoidable but recognized harm may ensue, this is known as the double effect. For example, respiratory depression caused by the administration of opiates for palliative sedation is well recognized, but its intended desired effect is not respiratory depression, but rather relief from suffering. Thus, palliative sedation is ethically acceptable, whereas euthanasia and assisted suicide are not. The process is similar but the intent is dichotomous.

As a result of several high-profile cases (Nancy Cruzan, Terri Schiavo), the US Supreme Court has judged that competent persons have a constitutionally protected liberty interest to refuse medical treatment, spurring more widespread discussion and adoption of living wills, advance directives, and health care proxy designations.

The principle of autonomy addresses the patient’s right to choose (voluntas aegroti suprema lex) and to make informed, uncoerced, voluntary decisions. Autonomy refers to each individual’s right to self-determination. Historically, US culture has placed great importance on and has had great respect for the principle of individual autonomy, a notion embodied in the Declaration of Independence, the US Constitution, and the Bill of Rights. The principle of autonomy is exemplified in the obligations to obtain informed consent, the adoption of living wills and advance directives, and health care proxy designations. The principle of autonomy requires health care surrogates (proxies) to use substituted judgment in decision making, whereby the surrogate decides for the patient as he or she believes the patient would have done.

The principle of justice is bifurcated into distribution and retribution. Distributive justice is an ideal that concerns the hope that all are treated equally and with clear transparency with respect to access to and distribution of limited health care resources. Retributive justice addresses retrospective retaliation as punishment or prospective warnings of imminent punishment as a deterrent to certain actions. In some ways, justice represents the antithesis of the principle of autonomy. Whereas autonomy dictates that a patient’s interests are determinative, the principle of distributive justice dictates that the physician must consider the fair allocation of resources without discrimination. Triage in emergencies and in critical care settings represents application of the principle of distributive justice. Retributive justice is largely reserved for disciplinary and legal review.

The principle of paternalism refers to the instinct for professionals to unilaterally make decisions on behalf of others, regardless of their capability to do so themselves. In its extreme form, the paternalistic provider ignores the wishes and needs of the patient and is not reconcilable with the precept of autonomy. Less obtrusively, paternalism is also manifested when the physician subconsciously withholds crucial information in the belief that bad news, such as a terminal diagnoses or a poor prognosis, might inflict undue emotional distress. Paternalistic decision making is no longer acceptable in modern medicine.

B. Medical Errors and Patient Safety

The topics of medical error and patient safety attained national prominence in 2000 when the Institute of Medicine (IOM) published To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. In it the IOM purported that medical errors accounted for at least 98,000 inpatient deaths annually, or, at least 270 deaths daily (3). Medical error can be defined as a mistake, inadvertent occurrence, or unintended event in health care delivery that may or may not result in patient injury. The Institute of Medicine defines patient safety as “freedom from accidental injury” and has suggested 10 recommendations for improving both quality of care and patient safety (4):

1. Care based on continuous healing relationships

2. Customization based on patient needs and values

3. Establishment of the patient as the source of control

4. Shared knowledge and the free flow of information

5. Evidence-based decision making

6. Safety as a priority

7. Transparency

8. Anticipation of needs

9. Continuous reduction of waste

10. Cooperation among clinicians

Anesthesiology has a long history of leadership in quality and safety and was the first specialty to adopt a national standard for safety improvements and the first national foundation dedicated to patient safety (Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation). In 1978, Cooper et al. (5) retrospectively examined the role of human factors in anesthesia incidents and determined that 82% of the incidents deemed to be preventable involved human error and 14% involved equipment failures. Less commonly, errors were deemed due to faulty equipment design, experience, insufficient familiarity with equipment or with the surgical procedure, poor communication among personnel, haste or lack of precaution, and distraction. Critical cognitive processes that predispose to errors include unintentional actions in the performance of routine tasks, mistakes in judgment, and inadequate plans of action. In addition, errors are classified as either active failures (e.g., violations of rules) or latent failures (e.g., faulty organizational or systemic processes). Latent failures are often unrecognized and have high potential for future repetition. Error-prone systems are exemplified by the concept of the Swiss-cheese model of error, whereby each layer of activity within a system contains embedded latent failures (holes) that allow errors to pass undetected through the system resulting in an adverse event. When the error penetrates all but a final barrier, the result is a near miss. In general, the more complex the system is, the greater the potential for error. Lastly, anesthesia practice shares common characteristics of many complex systems: high-level technical requirements, the need for quick reaction times, 24-hour-a-day operations, fatigue related to long hours, production pressure that frequently involves tradeoffs between service and safety, and multidisciplinary team coordination.

VIDEO 40-2

VIDEO 40-2

Accident Causation

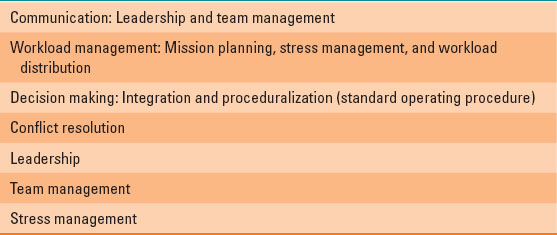

The medical model for team coordination for error prevention has its origins in the aviation industry, which developed the crew resource management (CRM) paradigm in 1978 (Table 40-1). CRM fosters an organizational culture that encourages each team member to respectfully question authority, while preserving authority and chain of command. CRM encompasses knowledge, skills, and attitudes including communications, situational awareness, problem solving, decision making, and teamwork. CRM is a team management system that makes optimum use of all available resources. These include equipment, procedures, and people in order to promote safety, enhance operational efficiency, and foster teamwork, as well as allowing patient involvement, transparency, and accountability. CRM has become an integral part of both anesthesiology simulator training and interdisciplinary trauma care (see Chapter 32).

Table 40-1 The Structure of Crew Resource Management

C. Informed Consent

A separate and distinct documentation of informed consent for anesthesia and for anesthesia-related procedures is widely held to be the standard. In addition, a patient’s ability to refuse a proposed intervention; to place limits, restrictions, or conditions on treatment; or disregard the advice of a physician altogether are all corollaries of the informed consent doctrine. Providers must understand and respect the fact that what may be consented to may also be refused. Documentation of refusal to consent is equally as important as the documentation of informed consent to treatment.

The doctrine of informed consent is premised on the ethical principle of autonomy that obliges physicians to respect patients’ right to bodily self-determination and therefore share medical decision-making authority with patients. The cornerstone of valid informed consent is effective communication—a two-way dialogue. There are two distinct legal standards that are applied to the informed consent process: the reasonable physician standard or the reasonable patient standard.

The reasonable patient standard is more commonly applied and is consistent with a respect for patient autonomy. It requires disclosure of the relevant information that a typical and reasonable patient would want to know in order to make an informed decision. The process of informed consent requires disclosure and discussion of all material risks, benefits, and alternatives to proposed therapeutic or investigational interventions.

All disclosure standards require that information and choices be presented comprehensively and in clear terms. This should include a concomitant explanation of the meaning of the terms, potential short-term and long-term implications of each option, discussions regarding the option to change the plan of care at a later time and the implications of such withdrawal, and reassurance that such decisions will be respected. The dialogue, including an opportunity for patients to ask questions and receive honest answers regarding the proposed treatment, should occur in an atmosphere devoid of any sense of duress or coercion in order for the consent to be truly valid.

Finally, after all disclosures have been made, the options considered, and the accord reached, then the signed form within the record will represent the formal documentation of the process. Consent is therefore somewhat analogous to a contract that not only requires truthful disclosure, consideration, and acceptance, but also imposes duties and obligations on the parties.

Similar to contracts, there are potential legal challenges regarding to the validity of the consent or contract. Such challenges include fraudulent facts or pretenses, duress, lack of capacity, or impaired judgment. A legally competent patient is one who is legally able to make decisions on his or her own behalf. Unemancipated minors, the mentally challenged, or the permanently disabled are possible examples of patients who may lack competency for autonomous decision making and therefore family or court-appointed guardians will make decisions on their behalf. The term capacity refers to an impairment in decision making that is more situational in context, for example, medications that impair judgment and reasoning; metabolic disturbances; or mental states such as depression, mania, psychosis, and delirium or confusion.

The majority of states have statutory requirements regarding informed consent, where failure to comply with statutory requirements for informed consent can put the provider at risk for a charge of professional misconduct. Medicare’s conditions of participation and the Joint Commission also separately mandate informed consent. If a course of medical care is litigated for any reason, the lack of documented informed consent can compromise the legal defensibility of that case.

The doctrine of implied consent can sometimes address the relatively common clinical situation where the provider could reasonably infer that a patient would have consented to the treatment. Implied consent is essentially a matter of the provider’s reasonable interpretation of the overall patient’s conduct to be consistent with an intention to authorize a procedure, even though express consent to treatment is lacking. Implied consent should be reserved for emergency care and situations where informed consent from a patient or surrogate is either very impracticable or impossible.

In the instance where a previously competent patient, or a patient with capacity, has clearly expressed their directives, these directives remain binding even after the patient loses competence or capacity. For example, in the case of an adult Jehovah’s Witness patient who expressly refuses blood transfusion and this directive is documented clearly in the record, most courts have held the family cannot overrule the patient’s decision after he or she loses capacity.

D. Importance of the Medical Record

The medical record serves medical, legal, and business purposes. It is an ongoing record of treatment that is used to record and communicate the circumstances of patient care to other providers, to substantiate and justify the medical reasoning involved in reaching a diagnosis and determining a plan of care, and to support a claim for reimbursement. The medical record is legally the work product of the health care team (Table 40-2). There are two aspects of medical records: the physical chart and the information contained on it. The patient has both the right of possession and the right of confidentiality to his or her medical information. The physical chart is the property of the medical provider who is the legal custodian

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree