DEFINITION

Transforaminal injections are injections delivered into an intervertebral foramen of the vertebral column. The target is typically the spinal that lies in the foramen. When used for diagnostic purposes, the drug injected is a local anesthetic agent. When used as a therapeutic intervention, a combination of a local anesthetic and a corticosteroid preparation is injected. Most operators use lidocaine (in concentrations of 0.5%, 1%, or 2%), although some use small volumes of bupivacaine (0.5%). The steroid preparation depends on operator preference and the availability of the preferred preparation. Choices include betamethasone, dexamethasone, triamcinolone, and methylprednisolone. In different jurisdictions around the world, some steroid preparations are proscribed for spinal use by the manufacturer.

Diagnostic transforaminal blocks are used to pinpoint the particular spinal nerve responsible for radicular pain when imaging studies are ambiguous. Some operators use them to confirm a diagnosis of discogenic pain. For diagnostic transforaminal injections, there are no published reports of complications, either because the procedure is not commonly practiced or because the agent injected is innocuous.

The situation is different for therapeutic transforaminal injections of corticosteroids. The procedure is widely practiced, and an abundance of literature on its complications has arisen.

SCOPE OF THE PROBLEM AND PROPOSED MECHANISM OF CAUSATION

SCOPE OF THE PROBLEM AND PROPOSED MECHANISM OF CAUSATION

Cervical Transforaminal Injections

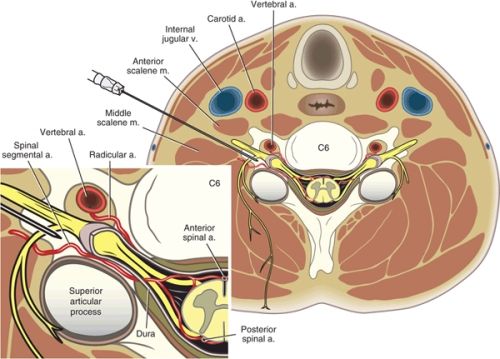

The hazards of cervical transforaminal injections are predicated by where the injection is performed and what is injected (Fig. 28-1). The needle is placed next to the spinal nerve and close to the dural sac and spinal cord. As well, the vertebral artery lies immediately outside the intervertebral foramen, and radicular arteries lie within the foramen. Each of these various anatomic relations has, to greater or lesser extents, been associated with complications.

FIGURE 28-1. Axial view of cervical transforaminal injection at the level of C6. The needle has been inserted along the axis of the foramen, and is in final position against the posterior aspect of the intervertebral foramen. Insertion along this axis places the needle behind the spinal nerve, and behind the vertebral artery, which lies anterior to the foramen. Inset: A spinal artery arises from the vertebral artery. It supplies the vertebral column. Another spinal artery enters the intervertebral foramen from the ascending cervical artery or deep cervical artery. It furnishes radicular branches that accompany the nerve roots and ultimately reach the anterior and posterior spinal arteries of the spinal cord. (Modified from Rathmell JP. Atlas of Image-guided Intervention in Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2012, with permission.)

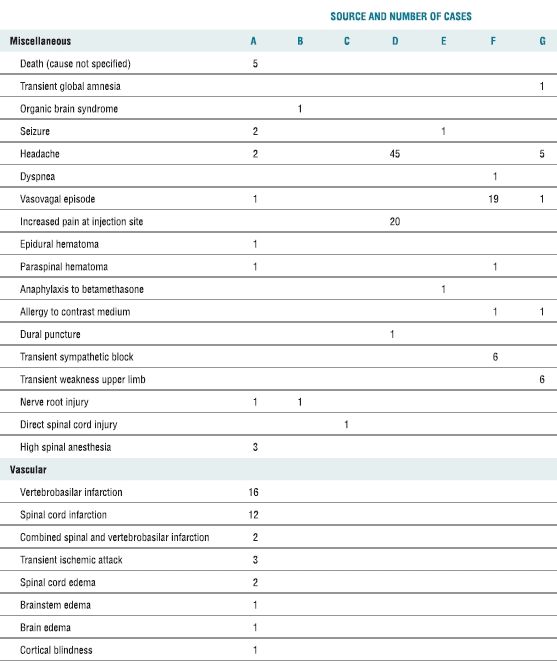

Complications have been described in case reports,1–9 in what amount to practice audits10–13 and in a survey of 1,340 physicians.14 The latter yielded 54 cases of complications, some of which included those described in the case reports. In broad terms, these complications can be categorized as miscellaneous and vascular (Table 28-1).

TABLE 28.1 Complications Associated with Cervical Transforaminal Injection of Steroids, as Reported by Various Authors

A. In a survey of 1,340 physicians.14

B. Case report.2

C. Case report.3

D. Practice audit of 89 procedures on 37 patients.12

E. Practice audit of 4,612 procedures.10

F. Practice audit of 799 procedures.11

G. Practice audit of 1,036 procedures.13

Some of the miscellaneous complications are enigmatic, for lack of sufficient information or because the cause of the complication was not pursued, such as death (cause not specified), transient amnesia, organic brain syndrome, seizure, headache, and dyspnea. Others are attributable to the needle and might apply to any paraspinal procedure, such as vasovagal episode, nausea, pain at the injection site, pain, and hematoma. Other complications are attributable to the agents injected, such as allergy to steroids or contrast medium. Some complications are idiosyncratic to the location of the injection in the cervical spine, such as dural puncture, sympathetic blockade, nerve root weakness, and nerve root injury. Direct spinal cord injury should not be a complication of cervical transforaminal injections, because guidelines for the procedure stipulate that the needle should be placed no further than midway across the intervertebral foramen and its position checked radiographically before any agent is injected.15,16 In the case reported3 (Table 28-1), the position of the needle was not checked before contrast medium was injected into the spinal cord. Similarly, high spinal anesthesia implies that the position of the needle was not checked before local anesthetic was injected intrathecally.

Some authors have identified complaints such as increased pain, light-headedness, and nausea as complications of cervical transforaminal injections.11,12 However, these complaints were no more common than in a control group who did not undergo injections.12 Therefore, they cannot be admitted as complications of transforaminal injections.

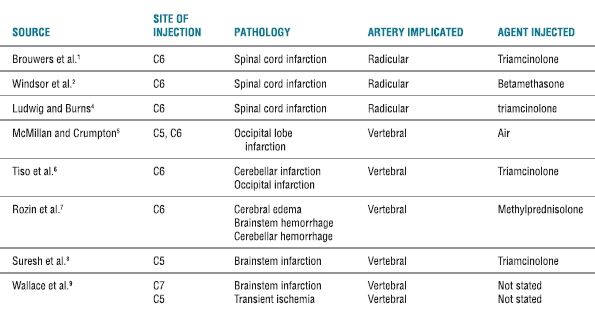

More often reported have been vascular complications. In addition to those listed in Table 28-1, several have been described in detail in case reports (Table 28-2). Vascular complications have involved the distribution of the vertebral artery or a radicular artery.

TABLE 28.2 Key Features of Case Reports of Vascular Complications of Cervical Transforaminal Injections of Corticosteroids

In the case of vertebrobasilar infarction, postulated causes include air embolism,5 vasospasm,14 aneurysm,7,14 and steroid embolism.6,14 Air embolism is certainly a risk if air is injected in an attempt to verify epidural placement of a needle; but doing so is neither a standard nor a common practice in the conduct of transforaminal injections. Vasospasm may sound attractive as a postulate, but is incompatible with past experience when radiologists were accustomed to directly puncturing vertebral arteries in the conduct of four-vessel angiography. Consequently, inducing a dissecting aneurysm, dislodging a mural plaque, and steroid embolism remain the likely causes of vertebrobasilar infarctions caused by cervical transforaminal injections. Passing a needle through the vertebral artery might dislodge a mural plaque. Injecting contrast medium or other material into the wall of the artery, instead of its lumen, could cause a dissecting aneurysm. Such a process has been verified at postmortem in two cases.9 Steroid embolism could occur if the position of the needle is not checked, and if flow of contrast medium into the vertebral artery is not recognized.

Laboratory studies have shown that triamcinolone, betamethasone, and methylprednisolone preparations each form particles or aggregates that are larger than red blood cells.6,17 Such particles or aggregates, therefore, could be capable of obstructing small vessels. Dexamethasone is the only commonly used corticosteroid that does not form particles or aggregates. It seems more than circumstantial that complications have been reported only in cases were particulate steroids have been used (Table 28-2). There have been no reports of complications when dexamethasone has been used.14

Two animal studies have demonstrated the ability of particulate steroids to cause infarctions. In one study, particular and nonparticular steroids were injected into the internal carotid artery of rats; lesions in the central nervous system occurred only in those animals into whom particular steroids were injected; no lesions, and no clinical deficits, were encountered in those animals injected with dexamethasone.18 In the other study, either particulate or nonparticulate steroids were injected into the vertebral arteries of pigs.19 All animals injected with particulate steroids failed to regain consciousness and showed clinical, magnetic resonance, and histopathologic features consistent with cerebrovascular insult. Animals who received nonparticulate steroids showed no evidence of neurologic injury, clinically, on imaging, or at postmortem.

In the case of spinal cord infarction, the leading contention is that the transforaminal injection compromises a radicular artery that happens to reinforce the anterior spinal artery (although in one case,2 a posterior spinal artery was implicated). Reinforcing radicular arteries can occur at any cervical level, but appear to be more common at lower cervical levels.20 Some authors have suggested that the needle used irritates the radicular artery in the intervertebral foramen and causes vasospasm.1,4,21 While this proposition is conceptually entertainable, no direct evidence of it has been produced. In contrast, circumstantial evidence does support the contention that, if unintentionally injected into a radicular artery, particulate steroids can act as an embolus and cause infarction in the territory of the anterior spinal artery.

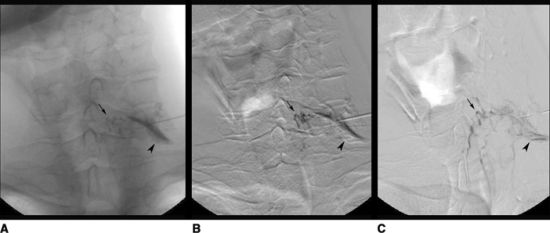

Two cases have been described in which digital subtraction angiography was used to capture images of a radicular artery during the injection of a test-dose of contrast medium in the course of a cervical transforaminal injection.20,22 These cases showed that intra-arterial injection could occur even if the needle was correctly placed in the posterior quadrant of the intervertebral foramen (Fig. 28-2). An additional case report showed filling of a radicular artery during an injection of contrast medium high in the foramen.23 In all three cases, filling of the radicular artery was recognized, the procedure was terminated, and the patient suffered no ill effects.

FIGURE 28-2. Anterior-posterior of the cervical spine during C7/T1 transforaminal injection (digital subtraction sequence after contrast injection). An anteroposterior view of an angiogram obtained after injection of contrast medium, prior to planned transforaminal injection of corticosteroids. An anteroposterior view of an angiogram obtained after injection of contrast medium,prior to planned transforaminal injection of corticosteroids. A: Image as seen on fluoroscopy. The needle lies in the left C7-T1 intervertebral foramen no further medially than its mediolateral point. Contrast medium outlines the exiting nerve root (arrowhead). The radicular artery appears as a thin thread passing medially from the site of injection (small arrow). B: Digital subtraction angiogram reveals the radicular artery extending medially more clearly (small arrow). C: Digital subtraction angiogram after pixel-shift re-registration reveals that the radicular artery (small arrow) extends to the midline to join the anterior spinal artery. Reproduced from Rathmell JP, Aprill C, Bogduk N. Cervical transforaminal injection of steroids. Anesthesiology 2004;100:1595–1600, with permission.)