Common Dermatologic Conditions

Goldie Gianoulis-Alissandratos RN, MS, FNP, DNC

Of all the body organs that make up an individual, the skin is the largest and most visible. Information about a person can be revealed through mechanisms acting within the skin such as happiness, humor, anger, fear, embarrassment, health, and sickness. Age is revealed principally through changes in the pattern, fine structure, and mechanical properties of skin. Genetics also plays a role in determining the uniqueness of an individual at the level of the skin.

The skin plays a major role in maintaining the body’s homeostasis. Through the maintenance of a constant body temperature, survival can be ensured. The skin serves as a barrier to prevent the loss of important body fluids and the entrance of possibly toxic environmental agents. The importance of the skin cannot be overlooked. Consider, for example, the color changes of the skin on a person in shock (pale, ashen) or a person with liver failure (yellow, jaundiced) or even a person with cardiac failure (blue, cyanotic). To the trained as well as the untrained eye, the skin may be an indicator of serious disease. The well-trained primary care provider, however, must be able to recognize the more subtle changes of the skin and distinguish between life-threatening diseases such as malignant melanoma and less serious, common skin conditions.

Patients present with skin lesions as an incidental finding or as the chief complaint. The role of the primary care provider in the diagnosis and treatment of common dermatologic conditions is increasingly important, because two thirds of these adult patients, who account for almost 10% of outpatient visits, will be seen by primary care providers. Furthermore, human suffering results from the disability, discomfort, and disfigurement that may be associated with various skin disorders. Through a relationship-centered approach, primary care providers may be able to assist their patients and help relieve their suffering.

Because of the nature of skin conditions, this chapter will include fundamental terms necessary to understand and describe skin lesions. Common skin diseases are then described in detail, including diagnosis and management.

ANATOMY, PHYSIOLOGY, AND PATHOLOGY

Skin Anatomy and physiology

The skin in composed of three layers: the epidermis, the dermis, and the subcutaneous tissues. Its outermost layer, the epidermis, is thin and devoid of blood vessels; therefore, it is dependent on the dermis for its nutrition. Melanin and keratin are formed in the epidermis. Well supplied with blood, the dermis also contains connective tissue, sebaceous glands, and some hair follicles. The dermis merges below with the sucutaneous layer, which contains fat, sweat glands, and the remainder of the hair follicles. Hair, nails, mucous membranes, and sebaceous and sweat glands are considered to be appendages of the skin.

Major functions of the skin include:

Protection from injurious external agents

Maintenance of an internal environment by providing a barrier to water and electrolyte loss

Regulation of body heat

Self-maintenance by the eccrine and sebaceous glands of a buffered protective skin film

Participation in Vitamin D production

Delayed hypersensitivity reaction to foreign substances

Sensation for touch, temperature, and pain.

Skin Disease Epidemiology

The true prevalence of skin disease is difficult to determine because many dermatologic studies have included only selected populations. Varying social and environmental factors also influence both the occurrence and the detection of skin disease. Persons whose occupation or hobbies require them to be outdoors may be more prone to the development of a skin cancer.

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

The diagnosis and treatment of skin disease depend on the health care provider’s familiarity with dermatology terms. Fitzpatrick and Bernhard (1993, p. 32) summed it up best when they said, “to read words, one must recognize letters; to read the skin, one must recognize the basic lesions.” A barrier to communication among providers exists because of the lack of any standardization of basic dermatologic terminology. The International League of Dermatologic Societies has published a glossary of basic lesions in an attempt to standardize the definitions. To prevent confusion in the standard of measurement of lesions, a metric ruler is an essential tool for the provider to ensure accurate documentation of lesion size.

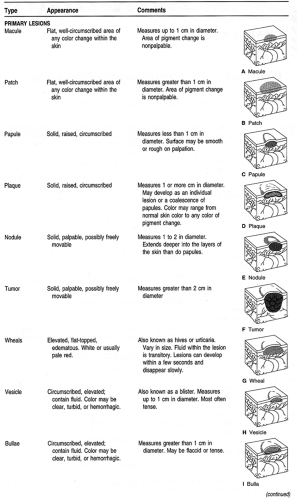

Primary Lesions

Primary lesions are the original lesions, whether they continue to full development or are modified by regression or trauma. These lesions assume a distinct characteristic (Table 15-1).

Secondary Lesions

Secondary lesions are simply lesions that have undergone changes from their primary form (see Table 15-1).

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The history of the present illness is critical in assessing a patient with a dermatologic concern. Along with the general medical history, a well-focused dermatologic history should be obtained. The history of a skin eruption should include:

The onset, development, and progression of the skin lesion or lesions. Particular questions should focus on any relation of the skin eruption to the patient’s occupation.

An accurate medication history, including prescription and nonprescription medications, and use of recreational drugs

Treatment obtained for any other ailment besides the skin eruption, including prescription and nonprescription medications

The effect of the skin eruption on exposure to sunlight and seasonal variations

Contact with animals, plants, chemicals, or metals

The ingestion of certain foods and beverages may contribute to or even be the actual cause of a skin eruption; therefore, detailed dietary questioning is warranted.

For the female patient, ask about any association of the skin eruption with menses or pregnancy.

In addition to the complete review of systems, constitutional symptoms that may indicate an acute illness syndrome or a chronic illness syndrome should be thoroughly investigated.

The physical examination must include the general appearance of the patient. A thorough head-to-toe examination of the skin should be conducted with proper lighting. Five major signs are assessed:

Type of lesion

Shape of lesion

Arrangement of multiple lesions

Color of lesion

Distribution of the lesions.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Laboratory Tests and Diagnostic Tools

A hand lens magnifier is needed to examine the surface and detail of skin lesions. Oblique lighting of the skin surface may help to detect slight degrees of elevation or depression of the skin eruption. Low illumination of a room enhances the contrast between hypopigmented or hyperpigmented skin with normal skin. A Wood’s lamp can be used to evaluate skin diseases that cause a loss or an increase in skin pigmentation; it should be used in a room that is completely dark. Diascopy is used to determine if a lesion is vascular. The examiner places a clear microscope slide or clear plastic ruler on the lesion while applying firm pressure. If the lesion turns white or fades as pressure is applied, the eruption is of vascular origin.

The dimple sign is a test used to aid in the differentiation of a benign lesion and a malignant melanoma. Lateral pressure is applied to the lesion with the thumb and index finger. If a dimpling occurs in the lesion, it is safe to assume that the lesion, which is most likely firm and pigmented, is not a melanoma.

Patch testing is used to aid in making the diagnosis and determining the causative agent of allergic contact dermatitis. Finn chambers are filled with specific allergens and usually placed on the patient’s back. After 48 hours the patches are removed and the initial reading is done. A positive reaction to a specific chemical would be localized to the area that had direct contact with that chemical only. It may present as a faint macular erythema or it may become ulcerative. Another reading must be obtained after an additional 24 hours to document any delayed hypersensitivity reactions.

Microscopic examinations are used frequently in dermatology and include Gram stains, cultures (both bacterial and fungal), potassium hydroxide preparations, Tzanck tests, and hair pluck evaluation.

A serologic test for syphilis should always be considered for a patient with generalized erythematous and scaling eruptions.

Biopsy of the skin is a useful diagnostic tool. In most instances the clinical and histologic findings should be in agreement. If they are not, another biopsy should be obtained. Follow-up with the patient after a few days or a week is recommended. The most common technique for a skin biopsy involves the use of a tool called a punch (a small, sterile, disposable tubular knife) under local anesthesia. The site of the biopsy is very important and usually depends on the stage of the eruption.

Elliptical excisions and scalpel wedge excisions can also be performed and sent for examination. The excision method used should be based on the practitioner’s experience and the laboratory’s requirements for the requested tests.

ACNE

Pathology and Etiology

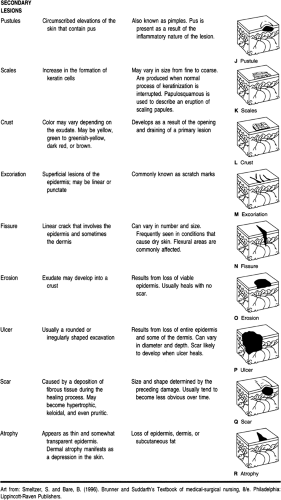

Acne vulgaris is a disease that affects the pilosebaceous unit and most commonly manifests on the chest, back, and face (Color Plate 1A–C). The pilosebaceous unit consists of sebaceous glands and hair follicles. These units are present on all skin surfaces except for the palms of the hands and soles of the feet.

Acne is a multifactorial disease that involves four principal factors in its pathogenesis: increased sebum production, abnormal keratinization of the follicular epithelium, proliferation of Propionibacterium acnes (P. acnes), and inflammation (Strauss, 1993).

INCREASED SEBUM PRODUCTION

Several factors influence sebum production, although the main influence is hormonal (Cunliffe & Gollnick, 1996). The secretory activity of the sebaceous gland is controlled by androgenic hormones (Leyden, 1995). Research has found that androgens are essential for the development of acne. No correlation, however, has been found between androgen levels and acne severity (Aizawa et al, 1995).

ABNORMAL KERATINIZATION OF THE FOLLICULAR EPITHELIUM

Abnormal or disordered shedding of the cells that line the sebaceous follicles is central to the pathogenesis of acne. This process is also known as follicular plugging (Arndt et al, 1995). The result of this abnormal shedding is comedo formation. If

the plug is formed within a dilated opening, it develops into a whitehead. If the comedonal mass protrudes from the sebaceous follicle, it develops into a blackhead. A whitehead is considered a closed comedo, whereas a blackhead is considered an open comedo (Leyden, 1995). These lesions, in and of themselves, are considered noninflammatory lesions of acne.

the plug is formed within a dilated opening, it develops into a whitehead. If the comedonal mass protrudes from the sebaceous follicle, it develops into a blackhead. A whitehead is considered a closed comedo, whereas a blackhead is considered an open comedo (Leyden, 1995). These lesions, in and of themselves, are considered noninflammatory lesions of acne.

PROLIFERATION OF P. ACNES AND INFLAMMATION

P. acnes is an anaerobic diphtheroid that colonizes sebaceous follicles (Thiboutot, 1996). It is transported to the skin surface along with the production of sebum (Webster, 1995). Inflammatory acne lesions, described as papules, pustules, nodules, cysts, and abscesses, are produced when P. acnes proliferates and generates an inflammatory reaction. Most inflammatory acne lesions result from the intrafollicular rupture of a comedo as opposed to a visible rupture (Arndt et al, 1995). Clinically detectable inflammation results once the comedonal contents are exposed to the immune system. The severity of the response is variable. It may present as small, superficial papules or pustules, with or without cysts or deep nodules. Spontaneous fluctuations in the degree of involvement are the rule rather than the exception.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Approximately 17 million people in the United States are afflicted with acne vulgaris (Kaminer & Gilchrest, 1995). In addition to disfigurement and scarring, acne may have an adverse effect on the victim’s psychological development. Although often associated with adolescence, acne may be first diagnosed in patients who are in their 30s or 40s. Research has identified problems for some persons with this condition in terms of self-esteem, self-confidence, body image, social withdrawal, depression, and anger (Bergfeld, 1995).

OPTIONS, EXPECTED OUTCOMES, COMPREHENSIVE MANAGEMENT

Acne vulgaris is rarely misdiagnosed. It may, however, become confused with folliculitis, rosacea, or any other acneiform eruption. The diagnosis is usually based on the finding of comedones, pustules, papules, nodules, or cysts on the back, chest, or face.

There are many myths regarding factors that may aggravate or alleviate acne. The most common myth is that various foods such as shellfish, chocolate, and fatty foods aggravate acne. There is no evidence to support the value of eliminating these foods (Strauss, 1993). For patients who attribute their acne flare-ups to their dietary intake, it is best to encourage them to eliminate the foods they think produce the flare-up.

Several studies have shown that genetic factors may influence the susceptibility to acne (Ebling & Cunliffe, 1992). Stress can aggravate acne but it is not a primary cause (Cunliffe & Gollnick, 1996). Acne itself can cause stress and is certainly aggravated by picking at or popping the lesions.

Acne vulgaris has a very favorable prognosis. Management of acne should be directed toward a combination of the four factors associated with acne. Scarring, which can be minimized with proper treatment, is the only sequela of acne. Acne is considered a chronic disease that requires months, if not years, of treatment. With the exception of isotretinoin, most therapies are prescribed on a long-term basis. Many treatment options are available, and treatment should be tailored to the patient based on the psychosocial impact the acne creates for the individual, as well as treatment costs.

TOPICAL THERAPY

Topical therapy is initially prescribed for patients with noninflammatory comedones. It may also be used for mild to moderate inflammatory acne. Topical therapies include comedolytic agents, antibiotics, and anti-inflammatory drugs.

COMEDOLYTIC AGENTS

The precursor of an acne lesion is the microcomedo. Therefore, therapy is initiated with a comedolytic agent.

Tretinoin

Tretinoin is an effective first-line comedolytic agent. It normalizes desquamation of the follicular epithelium and promotes drainage of pre-existing comedones. With continued use, normal shedding of follicular keratinocytes occurs within the lumen of the follicle (Thiboutot, 1996), preventing the development of new microcomedones.

There are various dosage forms and vehicle bases of tretinoin. It is usually applied once daily at bedtime after the face has been cleansed and adequate time allowed for it to dry. The mildest cream formulation should be prescribed first and the concentration increased depending on the clinical response. If the patient has excessively oily skin or lives in a humid climate, the gel formulation may be preferable. Dosage forms of tretinoin cream include 0.025%, 0.05%, and 0.1%. Gel formulation dosages include 0.01% and 0.025%. A 0.05% solution also exists. In terms of potency, the 0.05% cream and the 0.01% gel are roughly equivalent, as are the 0.1% cream and the 0.025% gel. The 0.05% solution is the most potent form of tretinoin.

Patients should always be informed of potential side effects, which include desquamation, burning, erythema, and exacerbation of inflammatory acne lesions. This irritation can be minimized by selecting the appropriate starting dose, applying the medication to dry skin, and increasing the concentration gradually. Tretinoin does not possess antimicrobial or anti-inflammatory activity. By reducing the number of microcomedones formed, a reduction in the number of inflammatory lesions can occur (Thiboutot, 1996).

Azelaic Acid Cream

Azelaic acid cream (20%) is a new topical therapy for acne that has recently become available in the United States. It is a naturally occurring compound that serves as an effective monotherapy in mild to moderate forms of acne (Graupe et al, 1996). The therapeutic benefits result from its ability to decrease the hyperproliferation of keratinocytes in the follicular infundibulum, an antibacterial effect against P. acnes, and direct anti-inflammatory properties. Azelaic acid cream has been found to have an overall efficacy comparable to that of 0.05% tretinoin, 5% benzoyl peroxide, and 2% topical erythromycin (Graupe et al, 1996). Significant advantages to the use of azelaic acid include excellent local tolerance and its favorable side effect profile: it is nonteratogenic, there are no photodynamic reactions, and it produces no induced resistance in P. acnes (Graupe et al, 1996). The proper application of azelaic acid cream is twice

a day (morning and evening). It should be rubbed into the skin gently until it vanishes.

a day (morning and evening). It should be rubbed into the skin gently until it vanishes.

Anti-inflammatory Agents

P. acnes is the stimulus for inflammatory acne. Suppression of this organism will result in an improvement of inflammatory lesions. Topical antibiotics decrease the formation of P. acnes and possess intrinsic anti-inflammatory activity as well (Thiboutot, 1996). Antimicrobial agents, such as tetracycline and erythromycin, may also decrease the inflammatory potential of P. acnes (Webster, 1995).

Benzoyl peroxide is a potent bactericidal agent effective against P. acnes. It is considered a first-line choice of therapy in mild inflammatory acne (Thiboutot, 1996). Benzoyl peroxide is formulated as a wash, cream, lotion, or gel. It is available in concentrations of 2%, 5%, and 10%. It may be used once or twice daily. The more common side effects include erythema and dryness. It may also bleach clothing, which is an important consideration when the benzoyl peroxide is applied to the chest or back.

The more commonly used topical antibiotics include clindamycin, erythromycin, and sulfur. They are available in various formulations, including gels, lotions, solutions, and pads. In general, lotions are less drying to the skin than gels or pads; solutions tend to be more drying to the skin. The provider must always consider allergies that the patient may have and prescribe a topical antibiotic accordingly. Side effects include local irritation and the development of resistant bacteria. Topical antibiotics are effective for mild to moderate inflammatory acne, especially when used in combination with a comedolytic agent.

Topical clindamycin and erythromycin are available as solutions, lotions, pads, or gels. They may be used once or twice daily, depending on whether they are prescribed alone or with a comedolytic agent.

Topical sulfur is available as a lotion only. It can be used once or twice daily, depending on whether it is prescribed alone or in combination with a comedolytic agent. This particular lotion is also available in a tinted version, which would be a ideal choice for patients who would like to cover their acne lesions.

COMBINATION THERAPY

Studies have been done to test the efficacy and safety of various combinations. Tretinoin has been found to increase the penetration of other topical agents used in combination with it (Bearson & Shalita, 1995). It has also been found that when all lesion types are considered, the concurrent use of topical clindamycin and tretinoin, or clindamycin and benzoyl peroxide, is clinically superior to either of the agents used alone (Bearson & Shalita, 1995). These combinations also make the treatment better tolerated because the irritant effects of one agent are decreased with the addition of the other.

There has been a recent surge in the use of alpha-hydroxy acids in the treatment of both inflammatory and noninflammatory acne. The mechanism of action that has been proposed for these acids is their keratolytic activity. They are most effective when used as an adjunctive therapy, not alone (Bearson & Shalita, 1995).

SYSTEMIC THERAPY

Systemic drugs are usually added to the treatment regimen when inflammatory disease, whether mild, moderate, or severe, does not respond to topical combinations. The more commonly used oral antibiotics include tetracycline, erythromycin, and minocycline. The mechanism of action common among these antibiotics is their antibacterial effect against P. acnes. Many of them possess intrinsic anti-inflammatory activity as well as the ability to alter sebum production (Thiboutot, 1996).

Tetracyclines and Erythromycin

Tetracyclines are the mainstay of acne therapy. Tetracycline itself does not directly alter sebum production but it does decrease the concentration of free fatty acids, which has a direct effect on the secretion of other proinflammatory products (Strauss, 1993). Common side effects of tetracycline include gastrointestinal upset, vaginal candidiasis, phototoxicity, and decreased effectiveness of oral contraceptives. Because dairy products and iron can decrease the absorption of tetracycline, it should be taken on an empty stomach, preferably with a glass of water. Tetracyclines have the ability to mineralize tissues rapidly and are deposited in developing teeth; this may cause irreversible yellow-brown staining. Tetracyclines have also been reported to inhibit fetal skeletal growth (Strauss, 1993). Therefore, they should never be prescribed to pregnant women or to babies.

Minocycline, a tetracycline derivative, is commonly used in patients whose acne is unresponsive to tetracycline. It is a potent antibacterial agent with the ability to penetrate the sebaceous gland (Bearson & Shalita, 1995). It is less likely to cause gastrointestinal upset and phototoxic reactions, but these side effects may still occur. One common side effect associated with minocycline is vertigo-like symptoms. This can sometimes be avoided by gradually increasing the dose. Other potential side effects include slate-blue pigmentation (particularly in acne scars), headache, pseudotumor cerebri, and tooth discoloration, as with other tetracyclines.

Erythromycin is comparable to tetracycline in its efficacy (Thiboutot, 1996). However, the possibility of developing resistance is greater with erythromycin (Bearson & Shalita, 1995). It should be taken with food or milk to decrease the possibility of gastrointestinal upset. There is a theoretical risk of a decrease in the efficacy of oral contraceptives, but less than that with oral tetracyclines (Thiboutot, 1996). Erythromycin is a good alternative for photosensitive patients.

The dosages of tetracycline and erythromycin are usually 500 to 1000 mg/day. Minocycline is given at a dosage of 100 to 200 mg/day. The medications are usually taken twice daily in equally divided doses. It is important to inform patients that there is usually little improvement within the first month of therapy. As improvement of the acne condition is noted, the dosage of the oral antibiotic is decreased. Topical therapy should remain unchanged. Patients should always be informed of the possibility of restarting the oral antibiotic if an exacerbation occurs.

Isotretinoin

Isotretinoin is a synthetic oral retinoid. It is an analogue of vitamin A. The indication for isotretinoin is inflammatory acne or cystic acne that does not respond to conventional therapy. Isotretinoin is the only form of therapy that directly affects all

four of the pathogenic factors of acne (Berson & Shalita, 1995). It has a direct influence on the abnormal keratinization of the follicle. A decrease in sebum production occurs as a result of sebaceous gland activity inhibition. Therefore, “the growth of P. acnes and its ability to generate proinflammatory mediators are diminished” (Bearson & Shalita, 1995, p. 37).

four of the pathogenic factors of acne (Berson & Shalita, 1995). It has a direct influence on the abnormal keratinization of the follicle. A decrease in sebum production occurs as a result of sebaceous gland activity inhibition. Therefore, “the growth of P. acnes and its ability to generate proinflammatory mediators are diminished” (Bearson & Shalita, 1995, p. 37).

The minimal dosage for isotretinoin is 1 mg/kg/day for 20 weeks. Some providers initiate therapy at 1.5 mg/kg/day. Dosages as high as 2 mg/kg/day are indicated for patients with severe trunk involvement or resistant chest, back, and facial lesions (Strauss, 1993). Isotretinoin is an extremely effective drug (Berson & Shalita, 1995). Patients must be warned about the possibility of an acne flare-up during the initial 3 to 4 weeks of therapy. Maximum improvement continues for 6 to 8 weeks after the cessation of therapy (Strauss, 1993).

The use of isotretinoin must be carefully monitored. A complete blood count, serum chemistries, and levels of hepatic enzymes, cholesterol, and triglycerides should be obtained before initiating therapy and monthly thereafter. The greatest concern is the risk of the drug being administered during pregnancy. Isotretinoin is a teratogen (Berson & Shalita, 1995), making pregnancy an absolute contraindication. Women of childbearing age should be told to begin therapy on the second day of their menstrual cycle. A negative serum pregnancy test should be obtained within 2 weeks of initiation of therapy and monthly thereafter. Sexually active females should use two methods of birth control starting at least 1 month before therapy begins. These contraceptive methods should continue throughout the course of treatment and for 1 month after the cessation of treatment. No more than a 1-month prescription should be given to a female patient to reinforce her awareness of the hazards of pregnancy while taking this medication. Signed informed consent that the patient understands the risks and benefits of using this drug and becoming pregnant should be obtained.

Every patient taking isotretinoin will develop some degree of mucocutaneous side effects, which may be controlled with the use of emollients. Secondary infection of the skin with Staphylococcus aureus may complicate the mucocutaneous side effects. If this develops, a course of antibiotic therapy with either dicloxacillin or erythromycin is warranted. Benign intracranial hypertension, myalgia, arthralgia, and rarely diffuse interstitial skeletal hyperostosis are considered systemic side effects of isotretinoin (Cunliffe & Gollnick, 1996).

PSORIASIS

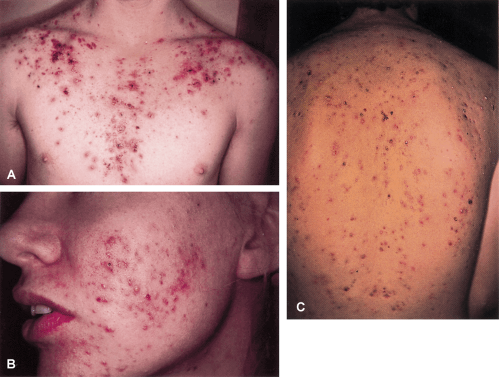

Psoriasis is one of the earliest skin diseases described. References date back to the Old Testament, where the general term lepra was used to describe various skin conditions, including psoriasis (Stern & Wu, 1996) (Color Plate 2).

Anatomy, Physiology, and Pathology

PATHOLOGY

Despite intensive research, little is known beyond the observation that psoriasis is characterized by an excessively rapid turnover of epidermal cells and inflammation (Christophers & Sterry, 1993). The generally accepted fundamental elements in the pathophysiologic mechanisms of psoriasis are accelerated proliferation of keratinocytes and disturbed maturation, altered cyclic nucleotide levels, associated changes in polymorphonuclear leukocyte and prostaglandin biology, and dermal vascular abnormalities (Grizzard, 1991).

Epidemiology

For millions of people, “the heartbreak of psoriasis” is not just a familiar advertising slogan but an unfortunate fact of life. Psoriasis can wreak havoc not only on its victims’ skin, but also on their lives. Dermatologists have always known that psoriasis increases the patient’s stress and that increased stress exacerbates psoriasis. This is a vicious cycle, leading to discomfort and despair for both patient and provider alike.

Although rarely life-threatening, psoriasis has a social and economic impact that is frequently underestimated (Ginsburg, 1995). This skin disorder is a chronic, genetically influenced, remitting and relapsing, scaly inflammatory eruption affecting 1% to 3% of the population (Greaves & Weinstein, 1995). Control of this lifelong disease poses a great challenge to the patient, family, provider, and community. “Psoriasis is a disease that, in attacking the skin, attacks the very identity of the individual. Many patients have to deal on a daily basis with shame, guilt, anger, and fear of being thought dirty and infectious by others” (Ginsburg, 1995, p. 793).

Clinical Presentation

Because of the dynamic nature of psoriasis and the varied presentations of this disease, it is often confused with other dermatologic conditions. Psoriasis typically reveals itself in five different variations (Lowe, 1993):

Plaque psoriasis

Pustular psoriasis

Guttate psoriasis

Inverse psoriasis

Erythrodermic psoriasis.

More than one pattern of psoriasis may be present at the same time. Each person with psoriasis is unique. A thorough skin examination is the crucial first step in diagnosing and managing patients with psoriasis.

PLAQUE PSORIASIS

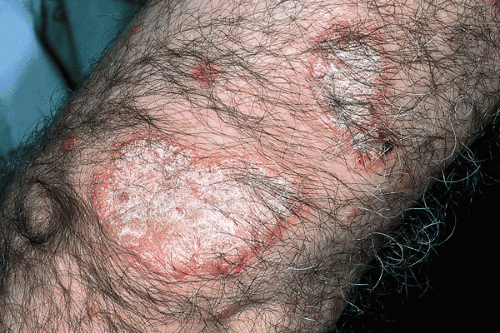

The classical clinical appearance of plaque psoriasis is a well-demarcated, erythematous, scaling, and often raised lesion (Color Plate 3). These lesions account for the designation of psoriasis as a papulosquamous disorder. A plaque-type pattern of psoriasis occurs more frequently than any other (Stern & Wu, 1996). The scales, often silvery and thickened, may occur anywhere on the body and are usually relatively symmetrical. The most likely areas of involvement are the elbows, knees, scalp, and lower back. Usually plaque psoriasis has a gradual onset and chronic course. Complete spontaneous remission is unusual (Stern & Wu, 1996).

PUSTULAR PSORIASIS

Pustular psoriasis can be localized or generalized and is subtyped accordingly. It is often found on the palms or soles. Instead of thickened scaling plaques, this type of psoriasis presents as erythematous plaques studded with pustules. Some cases of

pustular psoriasis may resolve spontaneously with supportive treatment only; in other cases, flare-ups and complications occur repeatedly.

pustular psoriasis may resolve spontaneously with supportive treatment only; in other cases, flare-ups and complications occur repeatedly.

GUTTATE PSORIASIS

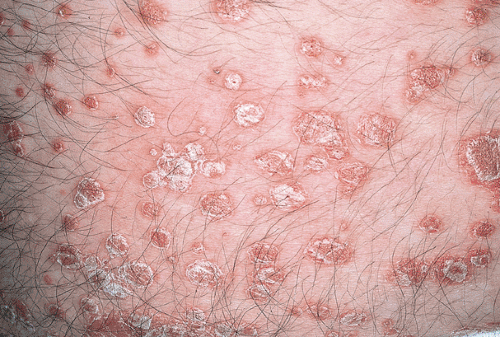

The typical presentation of guttate psoriasis is an acute generalized eruption of erythematous, scaling, raindrop-like papules (Color Plate 4). These single lesions rarely become confluent. The palms and soles are often spared. The most affected area is usually the trunk. Acute guttate psoriasis predominantly occurs during the second or third decade of life and is often precipitated by streptococcal throat infections (Christophers & Kiene, 1995). Guttate psoriasis carries a better prognosis than plaque-type psoriasis. It responds rapidly to ultraviolet light therapy, and spontaneous remission may occur.

INVERSE PSORIASIS

Psoriasis that affects the intertriginous regions, which include the axilla, groin, intergluteal fold, navel, and submammary region, is termed inverse psoriasis. Most patients have psoriasis lesions elsewhere, but these specific areas of involvement can cause severe discomfort and can even disable the patient. Patches of inverse psoriasis may be cracked and fissured. Consequently, these moist, macerated areas often become colonized with yeast and bacteria, making inverse psoriasis difficult to treat. Because of the maceration and friction associated with these specific areas, the scales of psoriasis are often absent (Stern & Wu, 1996).

ERYTHRODERMIC PSORIASIS

When psoriasis completely covers the body, it is referred to as exfoliative, generalized, or erythrodermic psoriasis. This is a severe, life-threatening eruption that most often manifests as intense pruritus, generalized erythema, and scaling. Fever, chills, pruritus, malaise, difficulty in regulating body temperature, and fatigue are systemic symptoms associated with this condition. Fortunately, this type of psoriasis occurs in fewer than 10% of patients (Lowe, 1993). Erythroderma may be a complication associated with pustular or plaque psoriasis, or it may even be the initial manifestation of psoriasis. After the erythrodermic flare subsides, patients usually revert to their original pattern of disease (Stern & Wu, 1996).

PSORIATIC ARTHRITIS

Arthritis is a common systemic component of psoriasis and is estimated to occur in 6% to 10% of cases (Grizzard, 1991). It is an inflammatory arthritis that may cause stiffness, pain, and a decrease in range of motion. Oligoarticular and polyarticular involvement, affecting the hands, feet, knees, wrists, and ankles, is common (Stern & Wu, 1996). There is no single diagnostic laboratory finding in psoriatic arthritis. It is a seronegative arthritis, and therefore a negative test for rheumatoid factor may aid with the diagnosis. Bulbal et al (1995) have commented on important considerations that providers should not overlook when evaluating someone with arthritis:

When considering psoriatic arthritis in the differential diagnosis, question the patient regarding any family history of psoriasis. A total body skin examination should also be performed in search of psoriatic lesions.

Septic arthritis should always be ruled out, even in patients with an established diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis.

Status of HIV infection should be considered in cases of fulminant disease.

Trigger Factors

A variety of stimuli, both local and systemic, have been reported to trigger the onset or exacerbation of psoriasis (Kadunce & Krueger, 1995). A genetic predisposition should always be taken into consideration. Pharmacologic triggers may include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, beta-blockers, antimalarial agents, lithium, and systemic corticosteroids. Clinical studies have confirmed that stress exacerbates psoriasis (Weller, 1996). Other stimuli include infection by Streptococcus pyogenes and HIV, and pregnancy and the use of progesterone-containing birth-control pills (Stern & Wu, 1996). Cutaneous trauma, also referred to as the Koebner phenomenon, is seen mainly in unstable psoriasis, and is the development of psoriasis in response to cutaneous injury.

Treatment Options, Expected Outcomes, Comprehensive Management

Psoriasis follows an irregular, chronic course marked by exacerbations of unpredictable onset and duration, as well as spontaneous remissions. Patients with newly developed psoriasis often become disenchanted with their treatment; if they do not accept that there is no cure, they may switch providers in the hope of finding one. Although there is no cure, treatment usually offers significant temporary relief and sometimes clears the rash. Because psoriasis is a lifelong disorder, optimal therapy should be simple and inexpensive, whenever possible. The severity of the disease and its impact, as perceived by the patient and provider together, can serve as a guide in developing a rational treatment plan. Seriously considering the way psoriasis affects the patient physically, socially, and psychologically should increase the patient’s participation in developing and maintaining the treatment plan. This in turn will be the best indicator of the effectiveness of the treatment plan.

The aim of treatment is to clear the skin and reverse inflammatory joint disease, if present. All too often, however, treatments that have kept the psoriasis in check will stop working. In cases where the condition becomes resistant, new therapeutic modalities are required.

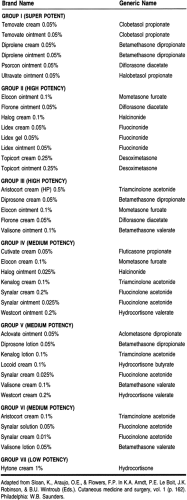

There is a wide spectrum of treatments. Common treatments for psoriasis include topical therapy, phototherapy and photochemotherapy, combination therapies, and systemic therapies. Generally, treatment begins with topical medications, proceeds to phototherapy or photochemotherapy in combination with the topical therapy, and finally leads to systemic therapy. Emollients are a very important adjunctive agent with both topical and systemic therapies. They assist with hydration of the skin and soften and loosen the hyperkeratotic scales. They are safe and relatively inexpensive (Table 15-2).

TOPICAL THERAPIES

Topical Corticosteroids

Topical corticosteroids are frequently prescribed as the initial therapy for mild to moderate plaque psoriasis. Although the exact mechanism of action in psoriasis remains unknown, corticosteroids

have anti-inflammatory, antiproliferative, and antimitotic properties (Katz, 1995).

have anti-inflammatory, antiproliferative, and antimitotic properties (Katz, 1995).

Topical corticosteroids are available in a variety of strengths and vehicles. They are categorized according to potency. Topical therapy is usually begun with a medium-strength agent. Higher-potency corticosteroids are most often reserved for plaques that are resistant to a weaker corticosteroid or are prescribed for short-term use in a patient with limited areas of involvement. Even with the high-potency agents, complete clearance occurs in only a minority of patients (Stern & Wu, 1996). Less potent steroids should be used for the face and intertriginous areas. By doing so, the risk of side effects is decreased.

Topical steroids are odorless, colorless, and relatively simple to use. The choice of vehicle is very important. Ointments are more potent than creams and provide the best delivery of the medication by acting as an occlusive agent. Ointments, however, have a greasy consistency and may be unpleasant. Creams are more tolerable but less effective. They are the vehicle of choice for intertriginous areas. Lotions penetrate less well but are more practical for hairy areas.

Topical steroids are generally applied twice a day. Use of ultrapotent steroids is limited to 2- to 3-week courses. Occlusive dressings enhance the delivery and increase the effectiveness of topical steroids. In general, however, occlusive dressings should not be used with high-potency steroids.

Side effects of topical steroids increase with the potency, amount, and length of treatment; the risk is also increased if they are used under occlusion. Local side effects, which may be seen after several weeks of treatment, include skin atrophy, telangiectasias, steroid acne, and a rebound worsening after discontinuing use. A rosacea-like syndrome may develop after long-term use of steroids on the face.

Anthralin

The mechanism of action of anthralin is unknown. Anthralin penetrates lesional skin more rapidly than normal skin (Stern & Wu, 1996). The irritation effect of anthralin causes a slight increase in the mitotic index in normal skin. In abnormal skin, continual use decreases proliferation gradually (Silverman et al, 1995). Anthralin should be used only to treat stable plaque psoriasis; the irritation it produces may aggravate erythrodermic and pustular psoriasis.

Anthralin is available in paste, cream, and ointment formulas. The paste allows the most precise application. The ointment and cream are easier to apply, but they may smear and therefore cause irritation of unaffected skin. A significant limitation to the use of anthralin is its staining properties. Staining of the skin and clothing is primarily caused by the oxidation of anthralin. Byproducts of oxidation bind to keratin, stain natural and synthetic fibers, and are increased by alkalis.

Tar Preparations

Tars are the products of the distillation of oil. The main type of tar used in psoriasis therapy is coal tar. Tar preparations have been used for many years as an adjunctive therapy with ultraviolet-B. They are messy and smelly; this limits their acceptability by patients. Tar has been reported to suppress epidermal hyperplasia in psoriasis (Silverman et al, 1995). Well-controlled trials, however, have failed to demonstrate substantial benefits when used as a monotherapy (Stern & Wu, 1996).

Vitamin D3 Analogues

The identification of a high-affinity receptor in most skin cells for vitamin D has led to both oral and topical use of vitamin D analogues in the treatment of psoriasis. Epidermal keratinocytes produce vitamin D3, metabolize it to its most active form, and respond with a decrease in proliferation and an increase in differentiation (Kragballe, 1995). Calcipotriene is currently the most promising analogues. The various clinical forms of psoriasis are not equally suitable for calcipotriol therapy. Calcipotriol is marketed for the treatment of plaque psoriasis. A cream and solution are also available. Even though calcipotriol usually decreases plaque thickness, some residual thickness often remains. Therefore, it may be necessary to supplement calcipotriol therapy with another antipsoriatic form of therapy. Skin irritation is the only local side effect noted with calcipotriol therapy. Skin atrophy and photosensitization have not been reported (Kragballe, 1995). Calcipotriol and the other topical vitamin D analogues are not teratogenic (Kragballe, 1995), but there are no data from clinical trials among pregnant women. It would be advisable to discontinue calcipotriol therapy if the patient becomes pregnant.

PHOTOTHERAPY AND PHOTOCHEMOTHERAPY

Phototherapy is the use of ultraviolet (UV) radiation to treat skin disorders. Light is absorbed by molecules in the skin, triggering a sequence of photochemical events that may alter the structure and function of the skin (Stern & Wu, 1996). Sunlight exposure has long been known to improve the symptoms of psoriasis. UVB may be used as a monotherapy or in combination with other therapies. UVA is used with topical or systemic photosensitizers. The use of exogenous photosensitizing agents to enhance the therapeutic effect of UV radiation is termed photochemotherapy.

UVB Phototherapy

The exact therapeutic mechanism of UVB in the treatment of psoriasis is unknown. Individual patient factors should govern the treatment schedules, although numerous protocols exist. Erythemogenic doses of UVB administered at least three times per week appear most effective (Stern & Wu, 1996). A hydrophobic emollient should be applied before each treatment to maximize UVB penetration. Treatments are continued until the lesions are cleared; 25 or more treatments are typically required. UVB maintenance therapy appears to prolong remission after clearing.

Photochemotherapy (PUVA)

PUVA is used to treat severe psoriasis. The mechanism of action is unknown. Treatment consists of oral ingestion of a potent photosensitizer at a constant dosage and variable doses of UVA, depending on the sensitivity of the patient. Treatments are given two or three times a week. In most patients, clearing occurs after 19 to 25 treatments (Christophers & Sterry, 1993). PUVA results in rapid pigmentation of the skin. To protect the eyes, UVA–blocking wraparound glasses should be worn while outdoors 24 hours after the ingestion of the photosensitizing agent. Ophthalmologic examinations should be performed before the initiation of PUVA and at yearly intervals thereafter. Long-term side effects make it necessary to restrict PUVA to patients with widespread and severe psoriasis. A major early side effect is pruritus. Late sequelae include long-term actinic skin damage (solar elastosis, dry and wrinkled skin) and hyper- and hypopigmentation. Skin cancers may also develop. All of these side effects are of considerable importance when deciding whether to begin PUVA therapy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree