Cirrhosis of the Liver

Rosalinda Margulies BSN, MPH, RNC

Albert D. Min MD

Cirrhosis of the liver is defined as the destruction of normal hepatic architecture through fibrosis and nodular regeneration. It is the seventh leading cause of death in the United States, and thus it is important for the primary care provider to formulate a comprehensive, collaborative plan to provide high-quality care in a cost-effective and efficient manner. This chapter will focus on the comprehensive approach used by the primary care provider in caring for patients with cirrhosis.

ANATOMY, PHYSIOLOGY, AND PATHOLOGY

The liver weighs approximately 1500 g. There are two anatomic lobes, the right one about six times the size of the left. The liver participates in multiple functions essential to life, including storage and metabolism of carbohydrates and detoxification of toxins. The clinical sequelae of cirrhosis result from necrosis and regeneration of liver cells, followed by an increase in fibrous tissue formation. The normal structure of the hepatic lobules is distorted, leading to impaired hepatocellular function, obstruction of bile flow through the liver, and alterations in hepatic blood flow. In cirrhosis, regardless of the etiology or clinical status, the triad of parenchymal necrosis, regeneration, and scarring is present (Conn & Atterbury, 1993).

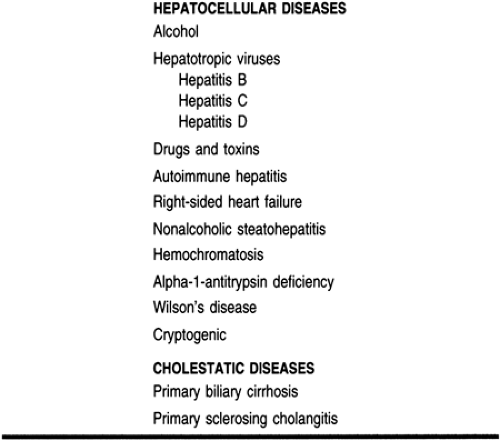

Although the mechanism of cirrhosis is unknown, its etiology is diverse and extensive. It may be classified into two major categories, hepatocellular and cholestatic liver diseases (Min & Bodenheimer, 1996). This is illustrated in Table 21-1.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Cirrhosis is the fourth leading cause of death in Caucasian American men between 25 and 64 years of age living in an urban setting (Bureau of Health Statistics, 1986). Alcoholic liver disease is a major clinical problem for primary care providers because early diagnosis is sometimes difficult and definitive treatment for alcoholism remains elusive. Alcoholism is the most common cause of chronic liver disease in Western societies, and approximately 18 million Americans abuse alcohol (Crabb & Lumeng, 1995). The peak prevalence of alcoholic liver disease occurs between 40 to 55 years of age. Incidence is disproportionately high in African Americans, Hispanics, and native Americans (Bureau of Health Statistics, 1986). In addition, cirrhosis accounts for 75% of all medical deaths among alcoholics. The male:female ratio in alcoholic liver disease is about 3:1 (Crabb & Lumeng, 1995).

Hepatitis B has a worldwide distribution and is the most common cause of chronic viral disease, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. End-stage liver disease from hepatitis C cirrhosis is responsible for 8000 to 10,000 deaths annually, and it is now the leading indication for liver transplantation in the United States (NIH, 1997).

Biliary cirrhosis is found in all races and occurs worldwide. It accounts for 0.6% to 2% of deaths from cirrhosis throughout the world (Kaplan, 1996).

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

A definite diagnosis of cirrhosis and its etiology can be usually made by a liver biopsy demonstrating characteristic histologic changes in conjunction with serologic tests and viral markers. Various serologic tests are useful as initial diagnostic measures, especially in patients with chronic hepatitis. A liver biopsy is often required to assess the degree of hepatocellular injury, in addition to pointing toward the etiology. Noninvasive radiologic imaging studies such as abdominal ultrasound with Doppler, computed tomography scanning, or magnetic resonance imaging do not have an important role in making the diagnosis of cirrhosis. Although either a nodular surface or an enlarged caudate lobe seen on these imaging studies may be suggestive of underlying cirrhosis, such findings are usually seen in advanced cirrhosis (Dodd, 1996). However, these studies are helpful and are often used to assess the size of the liver and the patency of hepatic vessels and to detect concomitant hepatic lesions.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

History

Patients with cirrhosis range from the asymptomatic, otherwise healthy patient to the patient presenting acutely with hepatocellular failure. However, more typical is the patient presenting with symptoms of fatigue, anorexia, insomnia, or pruritus of varying degrees. A detailed history is essential because it may point toward the etiology of the cirrhosis. Specific questions must be asked regarding risk factors for acquiring viral hepatitis, such as transfusion of blood products, history of intravenous drug abuse, sexual behavior, occupational hazards (eg, health care worker), and birthplace or travel in endemic areas. A family history of liver diseases is helpful in diseases such as hemochromatosis and Wilson’s disease. Obtaining a past medical or surgical history is warranted because associated extrahepatic diseases can often tip the possibility of a liver disease. The presence of inflammatory bowel disease in patients with abnormal liver chemistry results can lead to investigation of possible primary sclerosing cholangitis. Patients with decompensated liver diseases may have insomnia, abdominal discomfort, or a history of gastrointestinal bleeding.

Physical Examination

The physical examination is invaluable in establishing a diagnosis of cirrhosis. There may be evidence of temporal muscle wasting in a decompensated cirrhotic patient. Scleral icterus is usually

detected at total bilirubin levels above 3 to 4 mg/dL. Spider angiomas—visible small arterioles—are common, particularly on the upper arms and chest.

detected at total bilirubin levels above 3 to 4 mg/dL. Spider angiomas—visible small arterioles—are common, particularly on the upper arms and chest.

Several findings are noted on examination of the hand. Palmar erythema is characterized by redness of the ball of the palm with the thenar and hypothenar eminences. Dupuytren’s contracture may be a nonspecific finding but is often seen in alcoholic liver disease; it involves the fourth and fifth fingers because of thickening of the palmar fascia. White nails and clubbing are often present. Asterixis (flapping tremor) can also be noted in decompensated patients with hepatic encephalopathy.

Gynecomastia, testicular atrophy, and pectoral alopecia are also commonly present. Xanthelasma, xanthomas, and calcinosis can be seen in patients with biliary cirrhosis. Xanthelasmas usually occur below the inner canthal fold of the eye and the eyelid. Xanthomas are most commonly found in the creases of the hands, arms, and legs. Calcinoses typically occur at pressure points such as elbow and the ulnar surface of the forearm. Ascites, peripheral edema, splenomegaly, umbilical hernia, and caput medusae are seen in patients with advanced cirrhosis.

Disease Course

Patients with cirrhosis may live productive lives, but their disease may cause complications and death. Complications of cirrhosis include portal hypertension, often associated with the development of esophageal varices and ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Further, cirrhosis often leads to the development of hepatocellular carcinoma, especially in the setting of cirrhosis stemming from hepatitis B and C. Once a cirrhotic patient experiences a complication of portal hypertension with evidence of decreased hepatic synthetic function, the overall prognosis is very poor, and the patient should be evaluated for liver transplantation.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

The evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment of patients with cirrhosis are expensive endeavors. Duplicate workups, such as performing a liver and spleen nuclear scan in a patient scheduled for a liver biopsy, add little to the diagnosis and should be minimized. However, much of the costs are incurred during evaluation and symptomatic treatment of various complications of chronic liver disease, and optimal therapy without unnecessary costs can be obtained only with accurate diagnosis and evaluation.

Laboratory Tests

Routine laboratory tests play a crucial role in recognizing chronic liver disease and subsequently delineating the etiology, particularly in healthy, asymptomatic persons. Rather than a single specific test, the combination of several tests assessing different aspects of hepatic physiology, measured over a period of time, can lead to the diagnosis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree