Cardiomyopathies

Sanjeev Vaderah MD

Cardiomyopathies are a heterogeneous group of disorders that directly affect the heart muscle and cause abnormal myocardial performance. Cardiomyopathies do not include myocardial disease from secondary causes such as valvular heart disease, hypertension, or coronary artery disease. Although some cases of cardiomyopathy have a specific cause such as sarcoid or viral myocarditis, most cases are idiopathic.

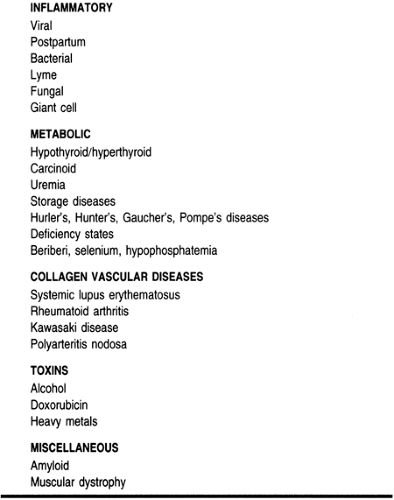

Cardiomyopathies may be grouped by etiology, as listed in Table 8-1, or classified by functional class. The functional classification places nearly all cardiomyopathies into one of three groups: dilated (or congestive), hypertrophic, or restrictive. This chapter will review cardiomyopathies using these three major functional classifications because diagnosis, therapy, and management are guided primarily by functional class regardless of etiology.

DILATED CARDIOMYOPATHY

Dilated cardiomyopathy is characterized by left or biventricular dilatation and systolic dysfunction. Idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy refers to dilated cardiomyopathy in the absence of hypertension or coronary, valvular, or pericardial disease.

Anatomy, Physiology, and Pathology

Abnormalities of both cellular and humoral elements have been implicated in the pathogenesis of dilated cardiomyopathy. Cardioselective M7 antimitochondrial antibodies have been identified in cases of both dilated and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. A genetic basis has been suggested based on the increased prevalence of HLA B27, HLA A2, HLA DQ4, and HLA DR4 antigens in cases of dilated cardiomyopathy (Anderson, 1984). Dilated cardiomyopathy can occur in healthy patients after a viral myocarditis, and enteroviral RNA sequences have been isolated from pathology specimens.

Ventricular dilatation is the chief morphologic feature. Cardiac mass is increased without ventricular wall thickening. Mural thrombi are often seen in both atria and ventricles. On histology, marked myocyte hypertrophy with large bizarre nuclei, myofilament loss, and varying degrees of replacement fibrosis are seen. These changes do not correlate with disease severity. Coronary arteries are normal (Fuster, 1994).

Epidemiology

The incidence varies from 3 to 10 per 100,000 population depending on the diagnostic criteria used (McKee et al, 1971; Torp, 1978). Dilated cardiomyopathy accounts for almost 20,000 deaths per annum. It can occur at any age, but the peak incidence is in the fourth and fifth decades. African American men have a 2.5 times higher risk than whites and women; this is unexplained by socioeconomic factors (Fuster, 1994).

Diagnostic Criteria

The echocardiogram is the best diagnostic tool. It typically shows dilated ventricles with global hypokinesis. Abnormal ventricular contractility is the sine qua non of idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy and an ejection fraction less than 45% is generally required for diagnosis (Fuster, 1994).

History and Physical Examination

Dilated cardiomyopathy presents with symptoms of congestive heart failure (eg, exertional dyspnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, orthopnea, peripheral edema). Abdominal pain from hepatic congestion may be present. Exertional chest pain indistinguishable from angina is present in almost a third of patients and may represent a reduced coronary reserve. Systemic and pulmonary emboli may also occur.

On the physical examination, resting tachycardia is commonly seen. Hemodynamics may be normal initially, but with the onset of heart failure, a narrow pulse pressure, pulsus alternans, and hypotension may be present. An S4 and murmurs of mitral or tricuspid regurgitation (because of the effect of chamber dilatation on valvular annulus) are common, and with advanced disease an S3 is heard. Cool, pale extremities are a subtle sign of systemic hypoperfusion.

Diagnostic Studies

The chest x-ray may show cardiomegaly, pulmonary vascular congestion, and pleural effusions. No characteristic abnormalities are present on the electrocardiogram; however, nonspecific ST–T changes and conduction abnormalities are commonly seen.

Echocardiography is an excellent tool for diagnosis. Ventricular mass, chamber dimensions, and cardiac function can all be accurately assessed noninvasively. Cardiac catheterization should be considered in most patients with risk factors for coronary artery disease or regional wall motion abnormalities on echocardiogram to exclude coronary artery disease, which may be reversible.

The main purpose of RV biopsy is to distinguish idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy from myocarditis. However, given its low diagnostic yield and lack of effective therapy for myocarditis, its role in clinical management is being re-evaluated.

Treatment Options and Expected Outcomes

A few causes of dilated cardiomyopathy (eg, endocrine and nutritional disorders) are reversible, and there are specific therapies for these. However, most cases are irreversible and therapy is supportive, identical to that for congestive heart failure.

Vasodilators, diuretics, and salt and fluid restriction are the mainstay of therapy. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors have been shown to reduce the mortality rate. A combination of isosorbide and hydralazine has similar benefits in patients who cannot tolerate ACE inhibitors.

Digoxin is the drug of choice to control the heart rate in atrial fibrillation. There is controversy about the role of digoxin in patients in sinus rhythm. Digoxin reduces symptoms and may reduce hospitalizations for congestive heart failure exacerbation (Digitalis Investigators Group, 1997).

Data have suggested that beta-blockers may improve hemodynamics and reduce the mortality rate. Potential mechanisms for benefit are protection from catecholamine toxicity, upregulation of myocardial beta-receptors, reduction in heart rate, and reduction in afterload (Schalant, ). Care must be taken to avoid precipitation of heart failure with beta-blockers. Carvedilol, an agent with both alpha- and beta-blocking properties, has demonstrated a significant reduction in the mortality rate from heart failure in clinical trials. Gradual increases in dosage and careful monitoring are mandatory whenever a beta-blocker is started in a patient with a dilated cardiomyopathy to avoid exacerbation of congestive hearth failure (Packer, 1996).

Although nonsustained ventricular tachycardia is commonly seen on Holter monitoring, routine antiarrhythmic therapy is not recommended. Patients with sustained ventricular tachycardia or syncope should undergo electrophysiologic stress testing and be considered for an automatic implantable cardioverter/defibrillator.

Chronic oral anticoagulation should be considered because of the high incidence of mural thrombi (Circulation, 1988), and the International Normalized Ratio (INR) should be maintained between 2 and 3.

Dilated cardiomyopathy is the most common indication for cardiac transplantation. This should be considered in younger patients with refractory heart failure and minimal comorbid conditions.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree