Bioterrorism

Ben Boedeker

Christian Popa

PART I SMALLPOX

CASE SUMMARY

A treaty verification monitor toured laboratories in the former Soviet Union where bioweapons were reported to have been made and stored during the cold war. He spent 5 days investigating the former bioweapons laboratory and then returned to his home in the Washington D.C. area. Fifteen days after visiting the test site, he presented to the general medical clinic at Fort Detrick, Maryland with fever of 38°C and a rash on his face and arms. The raised, slightly umbilicated lesions were 2 to 3 mm in diameter, and all were in the same apparent stage of development. Owing to the history of his recent trip to a bioweapons laboratory and his clinical presentation with a synchronous, centrifugal rash and fever, a presumptive diagnosis of smallpox was made. He was placed in isolation, and blood samples were taken for tissue culture of the presumed virus.

What Is Smallpox?

Smallpox, also known as variola major, is the only disease ever declared eradicated. The World Health Organization declared it globally eradicated in 1979. The only known samples of the virus are maintained by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) in the United States and, allegedly, by the former Soviet Union. The disease is highly infectious, has a high mortality rate, and a high secondary spread.1

▪ PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Smallpox is highly infectious by the aerosol route. The aerosol droplets are environmentally stable. The virus multiplies in the respiratory tract where it incubates 7 to 17 days. After an initial viremia to the lymph nodes, it spreads hematogenously to dermal blood vessels where it creates the characteristic skin change, termed pox.1,2

▪ SYMPTOMS AND MANIFESTATIONS

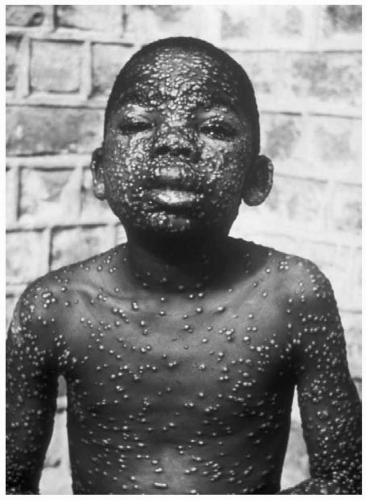

The symptoms begin acutely after a 7- to 17-day incubation period. Patients experience high fever, headache, rigors, malaise, myalgias, vomiting, and abdominal and back pain. After 2 to 3 days, a skin eruption develops on the face, hands, and forearms, and extends gradually to the trunk and lower extremities. These lesions progress synchronously, with macules changing in stages from papules to vesicles to pustules. They are often umbilicated (such as in molluscum contagiosum).1,2 (See Fig. 66.1). The characteristic rash occurs after 2 to 3 days of fever. It usually begins on the face, hands and forearms, and extends to the trunk and lower extremities. The lesions are synchronous, and all at the same stage of development, in contrast to a rash such as is seen with chickenpox where an older crusting lesion is seen in the same crop of lesions as a newly developing one. The smallpox rash will progress from macules to papules to vesicles to pustules in a centrifugal distribution. The rash scabs in 1 to 2 weeks, and leaves scars after the scabs fall off.1,2

What Are the Variants of Smallpox?

There are several variants of smallpox. Variola minor (alastrim) presents with similar cutaneous lesions as

variola major but they are smaller and fewer in number. Patients with variola minor are also not as ill as those with variola major.1,2 Three percent of patients present with hemorrhagic smallpox lesions. This group typically dies of the disease before papules develop.

variola major but they are smaller and fewer in number. Patients with variola minor are also not as ill as those with variola major.1,2 Three percent of patients present with hemorrhagic smallpox lesions. This group typically dies of the disease before papules develop.

Flat smallpox is another variant that occurs in approximately 4% of patients. These patients present with macular, soft, velvety lesions, and have a very poor prognosis. Modified smallpox can occur in patients who have been previously vaccinated. They develop a mild prodrome, and have rapid development of lesions which crust by day 7. Patients with modified disease typically form no pustules.1,3

What Is the Infectivity of Smallpox?

Patients with smallpox become infectious 3 to 6 days after the onset of fever. They remain infectious until the scabs heal (usually 3 weeks). During this time, they shed viral particles in oropharyngeal and respiratory secretions. Smallpox has approximately a 30% mortality in unvaccinated patients.1

How Is Smallpox Transmitted by the Infected Patient?

Any bodily secretion has the potential of transmitting smallpox. The virus can be shed in respiratory discharge, bed linens, the patient’s clothing, or skin contact with the scabs. To prevent transmission, handling of the patient should be done under strict sterile conditions, and the patient should be placed in total quarantine for 4 weeks after the rash develops.1

How Is the Diagnosis of Smallpox Made, and How Is It Treated?

▪ DIAGNOSIS

The initial diagnosis for smallpox should be made from the clinical presentation. This is important to allow quarantine and minimize disease spread. The definitive diagnosis is made by visualizing the virus from vesicular sampling through electron microscope and confirming by tissue culture.1

▪ TREATMENT

There is no primary treatment for smallpox. The cornerstone of treatment is quarantine to prevent spread and provide supportive care to the patient. To prevent spread, two “rings” of vaccination are done around each case. Anyone in contact with the patient during the infectious stage would be considered the first ring. The second ring of contacts would comprise any individuals who came into contact with the first ring. The first ring and second ring of individuals should be vaccinated and monitored. If both rings spike a fever, they are presumed to have smallpox and are quarantined.1,4 Immune globulin may also be available from the CDC for more severe cases. An antiviral drug, Cidofovir, has been shown to be effective in vitro.1

How Long Should a Patient Exposed to Smallpox Be Isolated?

Droplet and airborne precautions are required for a minimum of 17 days following exposure for all contacts. Patients should be considered infectious and kept quarantined until all scabs separate.1

Why Not Vaccinate Everyone to Prevent Smallpox?

A live vaccinia virus (cowpox) is used for smallpox inoculation. This live vaccine can itself cause significant complications. Encephalitis has been seen post vaccination in 12 per million vaccinated; it carries a 15% to 25% mortality rate, and 25% of survivors incur permanent neurologic deficits.1,5,6 Vaccinia gangrenosum can be seen in patients who are immunocompromised.

PART II ANTHRAX

CASE SUMMARY

A 52-year-old executive secretary was opening a letter for a Fortune 500 company president. She noticed a white powder on opening the letter. One day later, she developed a nonproductive cough, mild chest discomfort, malaise, fatigue, myalgia, and fever. She was seen by her family physician who diagnosed a viral syndrome. Two days later, she presented at the hospital with dyspnea, stridor, cyanosis, increased chest pain, and diaphoresis. Her temperature was 38°C. A chest radiograph showed widening of the mediastinum with pleural effusions. Cyanosis was developing. Gram stain of the blood revealed gram-positive bacilli in chains. She was hospitalized, and blood cultures were obtained to identify a suspected pneumonia with developing septicemia. On the third day, she went into severe shock and died. The autopsy revealed hemorrhagic mediastinitis and meningitis. Bacterial identification of anthrax was confirmed by the demonstration of the protective antigen toxin component, lysis by a specific bacteriophage, detection of capsule by fluorescent antibody, and virulence for mice and guinea pigs.

What Is Anthrax?

Anthrax is a zoonotic disease (can be transmitted from animals to humans) caused by Bacillus anthracis. The disease occurs in both domesticated and wild animals (primarily herbivores). Humans usually become infected by contact with infected animals or contaminated animal products.7

What Are Its Historic Considerations?

Anthrax was an economically important agricultural disease in the 16th through 18th centuries in Europe. The first live bacterial vaccine was made by Pasteur in 1881 for anthrax. When large numbers of animal hides were tanned during the industrial revolution, the anthrax spores on the animals’ hair were sometimes aerosolized, causing a pulmonary anthrax infection in tannery workers. This became known as Woolsorter’s Disease and is the first described occupational respiratory infectious agent. Owing to the lethality of pulmonary anthrax, this organism is a favorite of bioweaponeers.7

What Are the Characteristics of the Organism?

B. anthracis is a large, rod-shaped organism forming long chains described as “boxcars” on microscopy. It is a gram-positive bacillus, that is nonmotile, nonhemolytic, and encapsulated when cultured.7,8 It forms a resistant spore when exposed to oxygen (as when an infected animal is slaughtered and the meat is exposed to air). The spores are commonly ingested by grazing animals, where they enter the anaerobic gastrointestinal (GI) system and remain in a vegetative state.

The organism has three known virulence factors: an antiphagocytic capsule that protects it from the host’s macrophages and two protein exotoxins (lethal and edema toxin). The edema toxin enhances the organism’s ability to spread through tissue planes, and the lethal toxin kills host cells. The result of these actions are edema, hemorrhage, tissue necrosis, and a relative lack of leukocytes in the host.7,8

▪ PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The infection begins when the spores are inoculated through the skin or mucosa. It is believed that spores are ingested at the local site by macrophages, in which they germinate to the vegetative bacilli that produce the antiphagocytic capsule and toxins. At these sites, the bacteria proliferate and produce the edema and lethal toxins that impair host leukocyte function and lead to the distinctive pathologic findings of edema, hemorrhage, tissue necrosis, and a relative lack of leukocytes.

In inhalational anthrax, the spores are ingested by alveolar macrophages that transport them to the regional tracheobronchial lymph nodes, where germination occurs. There, the local production of toxins by extracellular bacilli gives rise to the characteristic pathologic picture: Massive hemorrhagic, edematous, and necrotizing lymphadenitis; and mediastinitis (the latter is almost pathognomonic of this disease).7 The bacilli can then spread to the blood, leading to septicemia with seeding of other organs, which frequently results in hemorrhagic meningitis. Terminally, toxin is present in high concentrations in the blood;8 however, both the site of toxin action and the molecular mechanism of death remain unknown. Death is the result of respiratory failure associated with pulmonary edema, overwhelming bacteremia, and, often, meningitis.7,8,9

How Does Infection Occur?

▪ ROUTES OF INFECTION

Human infection is usually through contact with infected animals or contaminated animal products. (See Fig. 66.2). This occurs predominantly through the cutaneous route (as through a cut in the skin when handling meat from an infected animal). Although rare, it can occur through the GI route when infected meat which has been inadequately cooked is ingested. Infections through the respiratory route are very rare in nature, but would be the most common path when anthrax is used as a bioweapon.7

Cutaneous

Patients with cutaneous anthrax will have a history of exposure to an infected animal. This is the most common form of naturally occurring anthrax, with an incubation period of 1 to 5 days. The patient develops a painless necrotic ulcer on the skin, commonly referred to as a pathognomic black eschar. They develop edema in the surrounding tissues (known as malignant edema). If cutaneous anthrax is untreated, it has a 21% risk of septicemia and death; however, if treated with the appropriate antibiotics, the mortality decreases to only 1%.7,9

Gastrointestinal

The patient with GI anthrax will have a history of eating infected meat that has not been cooked sufficiently. There is usually a 2- to 5-day incubation period, after which the patient develops a severe sore throat, abdominal distress, and signs of septicemia. Death usually ensues within 24 hours of the development of septicemia.7

Inhalational

The incubation period for inhalational anthrax is generally 1 to 6 days. The patients will initially present with fever, malaise, fatigue, cough, and mild chest discomfort and progresses by day 2 or 3 to severe respiratory distress with dyspnea, diaphoresis, stridor, cyanosis, and shock. Death typically occurs within 24 to 36 hours after the onset of severe symptoms.7,10,11

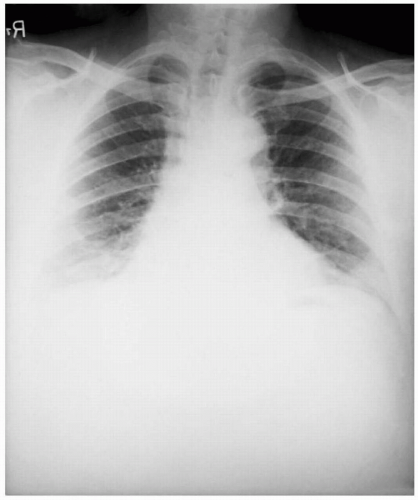

Diagnosis

The physical findings of inhalational anthrax are nonspecific, but the disease must be diagnosed rapidly to allow immediate treatment for any chance of survival. The chest radiograph will demonstrate a widened mediastinum. A noncontrast, computer tomography scan of the chest will show a hyperdense mediastinal adenopathy and diffuse mediastinal edema. Gram stain of the blood will show gram-positive bacilli in chains.7,10,11 Definitive diagnosis is accomplished by culture of the eschar lesion or blood culture. Other diagnostic tests that are not readily available include polymerase chain reaction (PCR), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), direct fluorescent antibody testing, and virulence for mice and guinea pigs.7,10,11

Treatment

Antibiotic treatment for inhalational anthrax must be initiated early, because it is usually futile once severe mediastinitis after spore inhalation or severe abdominal distress following spore ingestion occurs. Common acute treatment would include ciprofloxacin, 400 mg IV, every 8 to 12 hours or doxycycline, 100 mg IV, every 12 hours for 4 weeks. Vaccination should also begin at the start of drug therapy.7,12

How Do You Manage a Patient Who Has Been Exposed to Anthrax?

Postexposure prophylaxis is accomplished by Ciprofloxacin (500 mg PO q12h) for 4 weeks or Doxycycline (100 mg PO q12h) for 4 weeks. The antibiotic treatment is accompanied by the administration of the FDA-licensed anthrax vaccine series. However, because inhalational anthrax is not a commonly occurring disease in nature, it is impossible to test the efficacy of the vaccine against inhalational anthrax post vaccination.7,10,11,12,13,14,15

PART III PLAGUE

CASE SUMMARY

A 19-year-old college student went camping with friends in Colorado near a prairie dog town. One week after returning from the trip, she developed a swelling in her groin accompanied by a high fever. She reported to the student heath service where a gram stain of peripheral blood demonstrated a gram-negative organism in a safety pin pattern, characteristic for Yersinia pestis, which causes plague.

What Is Plague?

Plague is a zoonotic infection caused by Yersinia pestis, a gram-negative bacillus, which has been the cause of three great pandemics of human disease in the common era: 6th, 14th, and 20th centuries.16,17,18 The naturally occurring disease in humans is transmitted from rodents and is characterized by the abrupt onset of high fever, bacteremia, painful local lymphadenopathy draining from the exposure site (i.e., a bubo, the inflammatory swelling of one or more lymph nodes, usually in the groin; the confluent mass of nodes, if untreated, may suppurate and drain pus). Septicemic plague can sometimes ensue from untreated bubonic plague or, de novo, after a flea bite. Patients with the bubonic form of the disease may develop secondary pneumonic plague (also called plague pneumonia); this complication can lead to human-to-human spread by the respiratory route and cause primary pneumonic plague, the most severe and frequently fatal form of the disease.16

Plague can be found on all continents in the world. It is endemic in the continental United States and is especially prevalent from the eastern slope of the Rocky Mountains westward.2 Between 1970 and 1990, 56% of all cases occurred in New Mexico, 14% in Arizona, and 10% in Colorado.19

▪ MODE OF TRANSMISSION

Plague is usually transmitted by contact from fleas that live on infected rodents. The most common rodent in the United States, which carries this plague is the prairie dog. In other parts of the world, the rat is the most common carrier. When people are in close proximity to these rodents, the fleas, which usually infect the rodent, gain access to man. A bite from the flea will transmit Y. pestis to a human.16 As a biowarfare weapon, Y. pestis can be aerosolized, creating a venue for pneumonic plague.

▪ CHARACTERISTIC PRESENTATION

The patient presents with an abrupt onset of high fever and painful lymphadenopathy. The swollen lymph nodes are commonly referred to as bubos, which develop after 1 to 8 days of incubation, and are very painful. The patient commonly has vomiting, chills, fevers, severe malaise, headache, and altered mentation. The patient has a bacteremia and the organism can be seen in a peripheral blood smear.19

Some patients with bubonic plague may develop a secondary pneumonic plague. Patients can also acquire pneumonic plague directly from respiratory droplets from another patient with pneumonic plague. Patients with pneumonic plague commonly have a 2- to 3-day incubation after inoculation. This is followed by an abrupt onset of high fever, chills, malaise, productive cough with bloody sputum, and sepsis. The chest radiograph will reveal patchy infiltrates. There is 100% mortality without treatment in the first 24 hours. If plague were weaponized, the aerosol route would be the preferred method of delivery due to its higher lethality.16

Plague meningitis is seen in 6% to 7% of cases. The condition manifests itself most often in children after 9 to 14 days of ineffective treatment, with symptoms similar to those of other forms of acute bacterial meningitis.20

How Is Plague Diagnosed and Treated?

▪ DIAGNOSIS

Peripheral blood smears will reveal bipolar (safety pin-shaped) gram-negative bacilli. For pneumonic plague, the

patient will show a fulminant gram-negative pneumonia. Immunoassays are available to document plague.16

patient will show a fulminant gram-negative pneumonia. Immunoassays are available to document plague.16

▪ TREATMENT

It is important to isolate the patient for the first 48 hours to rule out pulmonary plague. If they are confirmed to have pulmonic plague, they should be isolated during the first 4 days of antibiotic treatment. Streptomycin is the drug of choice, followed by gentamicin; fluoroquinolones are usually also effective treatments.16 Early treatment is essential for this disease; if antibiotic therapy is delayed more than 1 day after the onset of symptoms, pneumonic plague is invariably fatal.16

What Precautions Protect a Health Care Worker Exposed to Patients with Plague?

A possible method of prophylaxis is doxycycline, 100 mg orally, twice daily for 7 days or for the duration of risk of exposure plus 1 week. In addition, it is important that contact and droplet precautions be observed and continued until pneumonic plague is ruled out, or sputum cultures are negative. There is also a vaccine available for plague.16,21

PART IV TULAREMIA

CASE SUMMARY

Two hunters were training a dog for rabbit hunting in a suburb of Washington, DC. Three or four days after the dog training session, both the hunters and their dog became ill. The dog had captured a wild rabbit during the training session, which was handled by the two men. The dog died from an apparent pneumonia 2 days later. One hunter developed a purulent lesion on his arm, a high fever, and a dry cough. He presented at a local emergency room 3 days after the hunting episode.

▪ CHARACTERISTICS

Francisella tularensis is a nonmotile, obligately aerobic, gram-negative coccobacillus. There are two variants.22,23 F. tularensis biovar tularensis is the most common isolate in the United States. It is recovered from rodents and ticks, and is highly virulent for rabbits and humans.

What Is the Likely Cause of This Illness?

The hunters contracted tularemia pneumonia due to exposure to the infected rabbit.

Tularemia is a bacterial zoonosis, and therefore can be transmitted from animal to man.22,23 The agent causing tularemia is F. tularensis (see Fig. 66.3), one of the most infectious pathogenic bacteria known, requiring inoculation or inhalation of as few as 10 organisms to cause the disease.22,23 Humans may become incidentally infected through diverse environmental exposures, such as in the example depicted. Although those infected can develop severe and sometimes fatal illness, they do not transmit infection to others. Tularemia is a dangerous potential biological weapon because of its extreme infectivity, ease of dissemination, and substantial capacity to cause illness and death with a small number of organisms.22,23,24

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree