INTRODUCTION

In austere situations, surgical instruments may need to be manufactured. Physician prisoners of war (POW) in World War II camps made surgical appliances from scrap materials using common items, including forks and spoons. With these rudimentary instruments, they performed thousands of successful operations.1,2

A relatively simple method for obtaining basic surgical equipment is to recycle instruments that are labeled as “single-use” or “disposable.” The most common of these are disposable suture and suture-removal kits. Made completely of metal, they can be easily sterilized and safely reused.

WOUND GLUES

While cyanoacrylate (e.g., “Superglue”), either the medical or the household variety, is the most commonly available glue to use for closing wounds, others can also be used. The problems with nonmedical cyanoacrylates are that they may not hold the tissue well, may irritate the tissues, and may even have some toxic properties. Among those that have been used are wood glue, panel adhesive, hobby cement, and various native substances. One caution: When using glue to close a wound, tell the patient that he or she should avoid putting an antibiotic ointment on the wound. Most have a petroleum base that will dissolve the glue.

Cyanoacrylate, which comes in a wide variety of commercial brands for medical and nonmedical use, is a methacrylate resin that bonds surfaces almost instantly. Nonmedical cyanoacrylate is not approved for medical use, although the medical literature shows that it has been used without difficulty in multiple situations. (Remember, the techniques in this book are primarily for austere medical circumstances; if approved compounds are available, use them.)

Cyanoacrylates have been used successfully as a wound adhesive, for emergency dental repairs, and to treat corneal ulcerations and perforations, urinary and esophagobronchial fistulas, variceal bleeding, and esophagogastric varices (obliteration). They have also been used to repair peripheral nerves and for therapeutic embolism of vascular abnormalities.3,4 During the Vietnam War, both liquid and spray forms of n-butyl cyanoacrylate were successfully used to control bleeding from penetrating wounds of the liver, retroperitoneum, kidney, pancreas, and vascular anastomoses after standard surgical treatment failed.5,6 Simple lacerations that are closed with tissue adhesive not only show no difference in cosmesis compared to those that are closed with sutures, but also have reduced pain scores and shorter procedure times.7

Nonmedical superglues effectively close wounds in a similar manner to medical tissue adhesives. However, they are not sterile, which is likely to have little impact. One benefit of the medical form, which is 2-octyl cyanoacrylate (2-OC), is that it forms a bond about four times stronger than does butyl cyanoacrylate.

The advantages of using cyanoacrylate are: (a) it is easy to obtain; (b) it can be applied rapidly; (c) it requires little technical knowledge; (d) a small amount can be used for many patients; (e) it can be used on many parts of the body (e.g., skin, oral, intra-abdominal); and (f) it is bactericidal against gram-positive (including multi-resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus) and, to a lesser extent, gram-negative organisms.8 Cyanoacrylate can also bolster thin edges of flaps or lacerations so that they can be primarily closed. This is particularly useful in the elderly and for those on chronic steroids.9 It can also protect skin that surrounds fistulas when other modalities are not available.10

The primary disadvantages to using cyanoacrylate on wounds are dehiscence and contamination of other body parts.

Because of cyanoacrylate’s lower tensile strength compared to sutures, wounds dehisce more readily than when closed with sutures. Lower the incidence of dehiscence by (a) not using it for wound closure over areas under tension, such as joints; and (b) using it only in areas and for wounds where a 5-0 suture would be appropriate.11

When using cyanoacrylate to close wounds around the eyes or the mouth, don’t let it get onto the lids or lips: It can seal them shut for hours. The easiest way to avoid this is to position the patient so that any extra cement will run away from, rather than toward, the patient’s eye or mouth. This may require having the patient turn his or her head away from the wound, lie on his or her side, sit up, or, if the wound is above the eye, lie in a Trendelenburg position.

Keep cyanoacrylate away from sensitive areas in two other ways: by using petroleum jelly (e.g., Vaseline) or an adhesive plastic drape. Petroleum jelly can be used to make a barrier around the wound to protect other tissues and sensitive areas (such as on the eyelids) from the adhesive.

If you have an adhesive drape (e.g., Tegaderm), fold it in half and cut a half-circle in the middle to make a hole. When opened, it forms a circular area that can be placed over the wound to be closed. The rest of the drape protects the surrounding areas. The edges of the drape closest to the wound must firmly adhere to the skin to make a successful barrier to the adhesive.

There are several treatment modalities if cyanoacrylate does get on an unwanted area during wound closure, or if someone tries to remove the cap with their teeth or accidentally squirts a cyanoacrylate tube at home.

To remove cyanoacrylate, most commonly from the eye or an eyelid, use a petroleum-based product such as ophthalmic bacitracin, erythromycin ointment, or mineral oil. The alternative is to wait (usually less than a day) and the lids will open without treatment.

Table 22-1 is a modified version of a list of complications seen with cyanoacrylate’s use on wounds. It was compiled by Dr. Loren Yamamoto from Kapiulani Medical Center in Hawaii.

| Complication | Solution/Prevention |

|---|---|

| Latex glove stuck to wound | Use vinyl gloves that can be removed with gentle tension. |

| Gauze stuck to wound | Use damp gauze rather than dry gauze. |

| Cyanoacrylate hardens inside wound | Maintain pressure on wound edges to prevent this. |

| Hematoma formation | Ensure hemostasis before using glue. |

| Adhesive applied over sutures | This makes suture removal difficult; don’t do it. |

STAPLES

Staples are a great way to rapidly close wounds. They can be used quickly for multiple patients on a variety of body parts. However, they cannot be improvised. The best suggestion, if you know that you will be in an austere medical situation, is to take staple guns and the staples with you. They are lightweight and relatively inexpensive. (Airlines may not permit you to have them in your carry-on luggage.)

To avoid using scarce resources to sedate a child while stapling a small laceration, use two people and two staple guns. Fire both at the same time; the child has a brief moment of pain, starts crying, and it is all over.

Other methods to bind wound edges together are the ordinary clips used to clamp paper pages together and safety pins—primarily to provide some closure to large gaping wounds. When passing the safety pin through the wound, engage enough tissue so that the wound doesn’t gape.13 Consider carrying several sizes of pins (see Appendix 2), from ¾- to 3-inches, to accommodate different wounds.

Nature’s staples (i.e., ant or other insect pincers) are used in remote areas of the world to close wounds. Do not try this at home! If a native healer with experience wants to use them, they will probably work well.

BINDING/TAPING

Use nearly any tape to close a wound. There is no magical quality to medical tapes. Other than cleaning and debriding the wound, this procedure requires no technical expertise and is amazingly fast, painless, and virtually cost free. Use duct tape (originally “Duck tape”), as well as any adhesive tape. Cut it lengthwise into strips if you want to be able to see part of the wound (Fig. 5-25).

Tapes do not stick well on areas that are hairy (shave the area, if necessary), wet or prone to perspiring, or under tension, such as joints. As with medical tape, you may need to use benzoin, cyanoacrylate, or another adhesive to help it stick. Alternatively, wrap a bandage around it, or use additional tape.

SUTURE MATERIALS

Many items can be used as suture materials. Some are used routinely (e.g., nylon fishing line) around the world. Others must be improvised from available materials. The key is to use common sense, but don’t be “picky.”

Purchase monofilament (suture material) in rolls. If used with ordinary sewing needles, the suture materials for a single operation cost almost nothing. Purchasing prepackaged monofilament suture material costs 20,000% more than buying it in reels.14

Often sold as “colorless fishing nylon,” fishing line is about 1/30 th to 1/500 th the cost of suture material sold in bulk. (Nylon carpet thread is very similar.) It can be precut to length and sterilized on the tray with other surgical instruments.15 It retains its strength after autoclaving, and, if translucent (uncolored) line is used, it is inert and nonallergenic once autoclaved. It provides comparable results to commercial nylon suture.16 If employing improvised needles made from hypodermic needles (for a method to make these, see the “Suture Needles” section below in this chapter), use the correct size line (Table 22-2).

| Nonabsorbable Suture Size, USP (Metric) | Diameter Limits, in mm | Fishing Line Size by Breaking Strength, in Pounds (Approximate Diameter, mm) | Uses | Minimum Improvised Syringe Needle Gauge (Inner Diameter, mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7-0 (0.5) | 0.045-0.60 | N/A | Corneas, blood vessels | N/A |

| 6-0 (0.7) | 0.070-0.099 | N/A | Face, eyelids, blood vessels | 31 (0.114 mm) |

| 5-0 (1) | 0.100-0.149 | 1 lb (0.12-0.14 mm) | Face, neck, blood vessels, plastic closures | 29 (0.165 mm) |

| 4-0 (1.5) | 0.150-0.199 | 2-4 lb (0.15-0.20 mm) | General use—neck, hands, limbs, tendons, scalp | 26 (0.241 mm) |

| 3-0 (2) | 0.200-0.249 | 6 lb (0.23-0.26 mm) | Limbs, trunk, scalp, bowel, over joints | 24 (0.292 mm) |

| 2-0 (3) | 0.300-0.339 | 8-10 lb (0.30-0.33 mm) | Trunk, fascia, viscera | 22 (0.394 mm) |

| 0 (3.5) | 0.350-0.399 | 12-14 lb (0.35-0.39 mm) | Very heavy suture—abdominal wall closure; fascia; muscle; suturing drains, tubes, and lines; bone | 22 (0.394 mm) |

| 1 (4) | 0.400-0.499 | 15-20 lb (0.40-0.48 mm) | 20 (0.584 mm) | |

| 2 (5) | 0.500-0.599 | 25-30 lb (0.50-0.58 mm) | 18 (0.838 mm) | |

| 3 and 4 (6) | 0.600-0.699 | N/A | 18 (0.838 mm) | |

| 5 (7) | 0.700-0.799 | 50 lb (0.70-0.77 mm) | 18 (0.838 mm) |

Scalp lacerations <10 cm long in patients with long hair (≥3 cm) near the wound can be closed by either tying or twisting hair on opposing sides of the wound. To tie the hair, twist a few strands together on each side of the laceration. Tie them and immediately secure them with benzoin, Nobecutane wound dressing, or a similar adhesive to prevent slippage. These knots will need to be cut out of the hair after the wound heals.

An alternative is to take several strands of hair from each side of the wound, pull them across the laceration to the opposite sides, and twist them around each other—once. Immediately put a drop of cyanoacrylate at the juncture. These will not have to be removed, because the cyanoacrylate will gradually wear off. Instruct patients not to wash their hair or put petroleum hair products near the wound for 48 hours. This technique is extremely fast, cost-effective, and can be done with virtually no technical skills or equipment.18,19

A fresh chicken egg membrane can be used to close wounds and reduce bleeding. The membrane contains types I, V, and X collagen, retains albumen, prevents penetration of bacteria, and is essential for the egg’s formation. This low-cost dressing has been used as a skin-graft donor-site dressing to relieve pain, protect the wound, and promote healing.20 One patient used a chicken egg membrane to close a full-thickness lip laceration, stop its profuse bleeding, and allow it to heal. He removed the membrane 3 days later and did well with no other therapy.21

Black or brown hairs from the tail of a horse make excellent sutures for skin wounds. They should be washed first with soap and water and then with alcohol. When needed, they are easily sterilized in boiling water or in steam. They are not as strong as silk.22

Frequently cited as a suture alternative, most dental floss approximates a size 0 or 00 suture. It also may be made of many different fibers (e.g., silk, nylon, or Teflon) and can be a single strand or braided.23 This should only be used as suture material as a last resort.

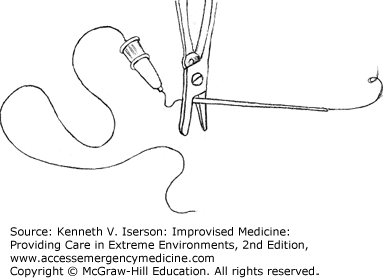

Wire is often used for surgical sutures. Nonsurgical stainless steel wire can easily be sterilized and used in a similar fashion. To swag it onto a needle requires using a large-gauge hypodermic needle (Fig. 22-1).

Cotton and linen threads have long been used as the standard surgical suture. Both are easily sterilized and do not irritate the skin. If using colored thread, choose one with a color-fast dye, or else boil it long enough to extract as much of the dye as possible.24 In austere circumstances, “use ordinary sewing cotton, No. 30, white, for the heavier work on the abdominal wall, and No. 40 or No. 50, black, for finer work on intestine or delicate tissues.”25

Rather than sterilization, high-level disinfection is most practical for the majority of alternative suture material. Disinfecton methods include boiling them in water or soaking them in alcohol (medicinal, drinking), hydrogen peroxide, bleach, surgical or regular soapy water, or lemon juice. Some residual substances (alcohol, bleach, lemon juice) on the suture may be painful if no local anesthetic is available.

To sterilize suture materials, wrap them in foil and either use an autoclaving method (see Chapter 6) or put them in or near the coals from a fire. How well that works without destroying the suture material will vary. Wire sutures can be flame-sterilized.

While infection arising from alternative suture materials depends on the material used, it is primarily a function of wound cleaning and debridement.