Introduction

Most babies make the transition to extrauterine life without assistance and breathe effectively within 90 s of birth. A small number need assistance with that transition and require airway management and sometimes establishment of breathing. The need for both ventilation and chest compressions in an apparently lifeless baby is a rare event affecting less than 0.1% of births. However, every newborn baby should be assessed at birth by someone who is trained in basic newborn resuscitation.

Babies considered to be at increased risk (Box 10.1) should be delivered in a unit with full newborn life support facilities. Delivery units should have guidelines to ensure appropriately trained professionals are available for such deliveries. These guidelines might entail attendance at 25% of all births, although most babies will not require any assistance. Even with such guidelines, help may still be unexpectedly required in a further 1.5% of births. This unpredictable need for resuscitation highlights the need for recognised newborn resuscitation courses (Box 10.2).

Equipment and temperature control

As the need for resuscitation cannot always be predicted, it is useful to plan for such an eventuality. Equipment that may be used to resuscitate a newborn baby is listed in Box 10.3. This is not an essential or exhaustive list and will vary between institutions. An appropriately trained person needs, as a minimum, a flat surface, warmth and a way to deliver air or oxygen at a controlled pressure. In delivery units, a resuscitaire fulfils these latter requirements. Current recommendations are to commence resuscitation with air and most modern resuscitaires have air–oxygen blenders which provide oxygen concentrations of 21–100%. It is the responsibility of all professionals to be fully conversant with the equipment available in their place of work.

Maternal

- Severe pregnancy-induced hypertension

- Diabetes mellitus

- Heavy sedation

- Severe maternal illness

Delivery

- Evidence of fetal compromise

- Abnormal presentation

- Prolapsed umbilical cord

- Antepartum haemorrhage

- Thick or old particulate meconium

- High instrumental delivery

- Class 1 caesarean section

Fetal

- Multiple pregnancy

- Prematurity (<34 weeks)

- Post-maturity (>42 weeks)

- In utero growth restriction

- Rhesus isoimmunisation

- Polyhydramnios and oligohydramnios

- Severe fetal abnormality

- A flat surface (resuscitaire in hospital)

- A source of warmth and dry towels

- A plastic wrap or bag and radiant heater for preterm babies

- A suction system with at least 12 FG catheters

- Face masks

- Self-inflating bag (500 ml) with pressure release valve or pressure-limiting device

- Source of air and/or oxygen

- Oropharyngeal airways

- Laryngoscopes with straight size 0 and 1 blades

- Nasogastric tubes

- Umbilical cord clamp

- Scissors

- Tracheal tubes 2.5–4.0 mm diameter

- Tracheal tube stylet

- Umbilical catherisation set

- Adhesive tape

- Disposable gloves

- Stethoscope and saturation monitor

Maintaining the baby’s temperature with dry covers and a radiant heater is essential, as even in environments of 20–24 °C the core temperature of vulnerable babies may drop by 5 °C in as many minutes.

Procedure at delivery

If time allows, ensure that equipment is ready and, if appropriate, introduce yourself to the parents. There is usually no need to immediately clamp the cord, particularly if the baby seems well. Unless the baby is clearly in need of immediate resuscitation, cord clamping can be delayed for at least 1 min after the complete delivery of the baby. Keep the baby warm and assess whether any intervention is going to be needed. If the baby is thought to need assistance, then this takes precedence and the cord may need to be clamped in order to deliver that assistance. Aspirating the pharynx used to be common practice but this is almost always unnecessary and it may cause a delay in spontaneous respirations and bradycardia.

Keeping the baby warm

With a large surface area to weight ratio, babies can lose heat very quickly. Dry the baby off immediately and then wrap in a dry towel. Cold babies use more oxygen and are more likely to become hypoglycaemic and acidotic. Ideally, delivery should take place in a warm room, and an overhead heater should be switched on. Overall, however, drying effectively and wrapping the baby using a warm dry towel is the most important factor in avoiding hypothermia. Ensure that the head is covered as this represents a significant part of the baby’s surface area.

A more effective way to keep small and low gestation babies (less than 28 weeks gestation) warm in the delivery room is to place them immediately (i.e. without drying) into a polythene covering and under a radiant heat source.

Assessment of the newborn baby

Whilst the baby is kept warm, an initial assessment is made of respiration, heart rate, colour and tone. Unlike resuscitation at other ages, it is essential to assess fully in order that one can judge the success of interventions. This is most true of heart rate and breathing, which guide further resuscitative efforts and which are the focus of subsequent assessments. However, a baby who is white and shut down peripherally is more likely to be acidotic and a baby who is atonic is likely to be unconscious.

Resuscitation procedure

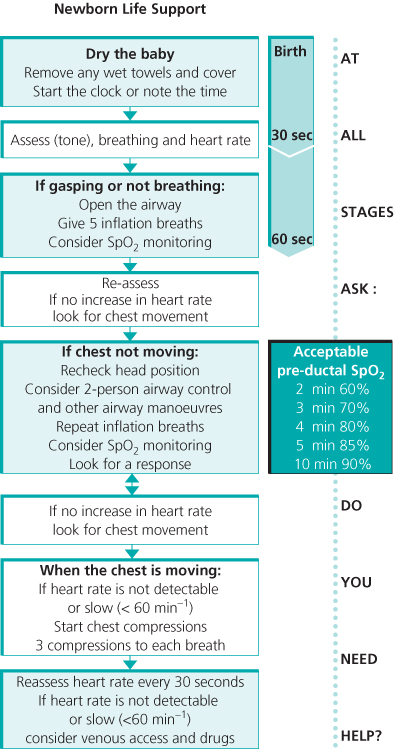

Most babies will start breathing within 10–20 s and establish spontaneous regular breathing sufficient to maintain the heart rate above 100 min−1 and improve colour within 90–180 s of birth. If apnoea or gasping persists after drying, intervention is required. Resuscitation should then follow the most recent standardised guidelines. These acknowledge that relatively few resuscitation interventions have been subject to randomised controlled trials. They are, however, based on as wide an examination of the evidence as possible. Resuscitation follows a standard Airway, Breathing, Circulation pathway, with the use of drugs in a tiny minority of cases (Figure 10.1).

Figure 10.1 Standard resuscitation guidelines. Reproduced with the kind permission of the Resuscitation Council (UK).