RECOVERY AND REHABILITATION

In trauma and emergency general surgery, a great deal of attention is often paid to the acute management of the injured or critically ill patient. While this focus reflects the initial and most time-sensitive aspects of patient care, it is important to remember that the traditional metrics of quality of care in this setting, namely, morbidity and mortality, tell us little about what is probably the most important outcome: the ability of the injured or ill individual to ultimately return to society as a functioning, productive citizen. This is reflected poignantly in the financial burden attributed to trauma by the CDC with 2000 data suggesting that injuries led to lifetime costs of $406 billion, with lost productivity costs totaling approximately $326 billion of this amount, or greater than four times the cost of medical care.1 This chapter provides information on the complex multidisciplinary care essential to the recovery and rehabilitation of the injured or critically ill surgical patient. While the chapter places emphasis on post-trauma rehabilitation due to the data that exists in this field, the principles contained within are applicable to all of acute care surgery, and may be utilized as such.

ADMISSION OF THE PATIENT TO THE HOSPITAL

Whether it is a trauma patient or an emergency general surgery patient, recovery and rehabilitation should start on admission to the hospital, or upon first encounter with the acute care surgeon. The interview and history should include where the patient lives, as many acute surgical patients are from surrounding local areas, or conversely from out of the surrounding area (vacation, work, visiting relatives, etc.). Who the patient lives with is equally important, as the patient living alone has vastly different needs from one who has the support of a spouse, siblings, parents, or children. Living conditions, such as single family home, multilevel home, apartment, or as has been seen in most recent times, whether the patient is homeless, also clearly have a role in disposition planning. Frank, open discussions with the patient’s family and friends will allow the clinician to gain valuable insight into the disposition planning that will need to be done once the primary surgical issues are resolved.

The physical examination of the acute surgical patient should also lead the physician to make certain early decisions about disposition. The multiple trauma patient with complex pelvic fractures and lower extremity fractures should lead one to conclude that ambulation may not be possible for weeks to months and a skilled nursing facility (SNF) may be a destination prior to a rehabilitation facility. A traumatic brain injury (TBI) will trigger a different set of potential destinations. An emergency general surgery patient who is going to receive a diverting or a permanent stoma will also present a different set of circumstances, and once again, open discussion with family members will yield important information regarding whether they will be comfortable caring for such a patient or whether a SNF may be needed.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY INPATIENT CONFERENCE FOR THE ACUTE CARE SURGERY PATIENT

Once the patient is admitted to the acute care hospital and once the surgical procedures have been performed, it is crucial to assemble a team of all the specialists involved in the patient’s care to plan immediately for the acute and chronic care of the patient. Many acute care services have daily “sit-down” rounds with team members; however, it is the opinion of the authors that at a minimum, twice-weekly “multidisciplinary rounds” be held with a team of surgical attendings, surgical residents if in a teaching environment, staff nurses from the patient floor and the intensive care unit, physical therapist, occupational therapist, social workers, speech pathologists, dietician, rehabilitation intake specialist, quality assurance staff (trauma service coordinators), and on occasion clergy and ethics panel members. The optimal days for these twice-weekly conferences would be on Monday, after the weekend to discuss all the new admissions and on Friday, before the weekend to make destination disposition plans prior to the weekend. Such conferences should become part of standard policy and procedures on the acute care surgery service. Further, the use of frequently updated, electronically generated lists should comprise every element of the patient’s status to reflect involvement of all the aforementioned disciplines. Trauma patients at designated or verified trauma centers may be bound by rules to have certain consultations from rehabilitation intake personnel and physicians within a certain time period varying from within 24 hours to 7 days of admission.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY REHABILITATION OF THE TRAUMA PATIENT

The multiply injured trauma patients must deal with the healing of both visible and invisible wounds following their traumatic insult. In order to provide optimal care, a team approach should be undertaken, and will necessarily incorporate specialists in a variety of fields to achieve the best possible outcome. As is true in the field of trauma as a whole, much has been learned about interdisciplinary rehabilitation as a result of military conflict. The recent campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan have generated a new series of challenges that have led to innovative responses that may be employed by providers taking on the responsibility of recuperating and rehabilitating the multiply injured patient.

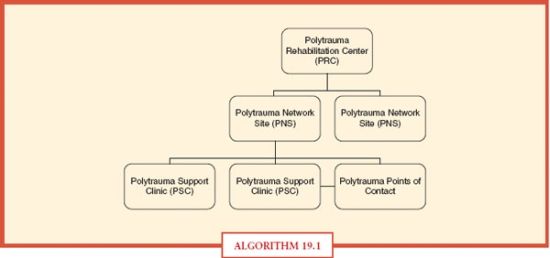

The Veterans Health Administration has outlined its system for interdisciplinary care, the Polytrauma System of Care (PSC), which grew out of the recognition of the complex care needs of the significant numbers of multiply injured soldiers returning from Iraq.2,3 The PSC is a VHA-wide, regionalized, tiered system of care delivery (Algorithm. 19.1). At the core of each region is the Polytrauma Rehabilitation Center (PRC), which delivers comprehensive medical, surgical, and rehabilitative care within the setting of a tertiary medical center. The PRC offers all potential services needed by the multiply injured as well as their families, and doubles as a consultation and education center for practitioners employed in other components in the region of that PRC. The next tier is the Polytrauma Network Site (PNS), which is geared toward the delivery of postacute inpatient rehabilitative care and has the responsibility of ongoing coordination of rehabilitation services for veterans and their families within their local area. The final tier is delivered at the local level in the form of Polytrauma Support Clinic Teams that accept and refer veterans and provide rehabilitative care to those with stable needs, and Polytrauma Points of Contact, comprised of individuals (primarily social workers) at various VA sites who provide no direct rehabilitative services, but assist veterans in receiving needed care on a local level.

ALGORITHM 19.1 The Veterans Health Administration Polytrauma System of Care. (Adapted from Sigford BJ. To care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan (Abraham Lincoln): the Department of Veterans Affairs polytrauma system of care Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89:160–162.)

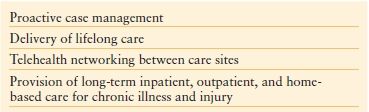

The PSC is guided by four tenets that govern care (Table 19.1). Proactive case management is carried out by nurses for clinical issues and social workers for psychosocial ones. Tasks include regular contact with patients to ensure appropriate execution of the plan of care, identifying changes in the social situation of the patient, coordinating resources, providing support and education, and helping patients make the transition from active duty to veteran status. As substantial, major multiple traumas often lead to long-term issues, the system is designed to deliver lifelong care via the PSC closest to the veteran. All centers within the system are linked by the Polytrauma Telehealth Network, which is a system of videoconferencing utilized in the coordinated care between practitioners, and in providing education and support to veterans and their families. Finally, severely injured veterans may require long-term care and assistance within facilities or within their homes, and the PSC is committed to providing this for injured veterans.

TABLE 19.1

KEY COMPONENTS OF THE VETERANS HEALTH ADMINISTRATION POLYTRAUMA SYSTEM OF CARE

Adapted from Sigford BJ. To care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan (Abraham Lincoln): the Department of Veterans Affairs polytrauma system of care Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89:160–162.

While the PSC provides what is perhaps in theory a model system for the delivery of interdisciplinary care for the multiply injured, it is unlikely that such a system could be implemented in the current civilian health care environment in the United States. A complex system with multiple, sometimes divergent interests, in which centers compete against one another for business, in which payor concerns often dictate the location and level of care afforded, and in which long-term follow-up and care is a luxury rather than the standard, the delivery of optimal multidisciplinary care is a challenging process. That said, the components are in place, and the key aspects and providers will be reviewed individually.

Social Work

The social worker is at the core of post-injury care planning and coordination. According to the National Association of Social Workers, “professional social workers assist individuals and groups to restore or enhance their capacity for social functioning, while creating societal conditions favorable to their goals. The practice of social work requires knowledge

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree