Pancreatitis: Acute and Chronic

Gwyneth Davis MD

Pancreatitis, an inflammatory disease of the pancreas, may be classified as acute or chronic. Most cases of acute pancreatitis are caused by either alcohol intake or gallstones. The clinical course may be mild, subsiding within 48 to 72 hours with conservative therapy, or may progress to necrosis and rapid deterioration to respiratory and other organ failure, sepsis, and death. Treatment is largely supportive, with intravenous hydration and parenteral analgesics. Treatment failure mandates a search for complications such as abscesses or pseudocysts.

The etiology of chronic pancreatitis is similar, with alcoholism as the predominant factor. Recurrent cholelithiasis or rarely hereditary factors or malnutrition (Sarner, 1995) may play a part in its pathogenesis. Continuing inflammation of the gland leads to fibrosis and a loss of exocrine and endocrine parenchyma. Pain is the predominant symptom until acinar tissue is completely effaced, at which point steatorrhea becomes the main problem (Braganza, 1996).

ANATOMY, PHYSIOLOGY, AND PATHOLOGY

The pancreas is a retort-shaped gland of soft consistency. It is more than 6″ long and has a finely lobulated surface. It lies somewhat obliquely, immediately behind the peritoneum of the posterior abdominal wall, and slopes from a large head, up through a neck and body, toward a narrow tail. The head lies in the C curve of the duodenum, and part of its posterior surface is prolonged and wedge-shaped, forming the uncinate process. The main pancreatic duct (Wirsung) is continuous from the tail to the head and joins the common bile duct at the ampulla of Vater, which then opens into the duodenum. The accessory pancreatic duct (Santorini) drains the uncinate process and lower part of the head and also opens into the duodenum separately from the main duct, although the two ducts often communicate. The blood supply is from the splenic and pancreaticoduodenal arteries; the corresponding veins drain into the portal system.

The pancreas has both endocrine (internal) and exocrine (external) secretory properties. The endocrine component of the pancreas consists of the islets of Langerhans. These produce insulin, glucagon, and somatostatin, which play a major role in the metabolism of food. Most endocrine tissue is contained in the tail and distal body of the pancreas. The exocrine pancreas consists of glandular, secretory units, the acinar cells. These produce and secrete pancreatic juice, which has two important components: bicarbonate (to neutralize stomach acid) and digestive enzymes, which are secreted into the duodenum via the main pancreatic duct.

ACUTE PANCREATITIS

Epidemiology and Etiology

An inflammatory process of the pancreas may subsequently involve other regional tissues or remote organ systems. The process can be mild or severe, mild being associated with minimal organ disruption and an uneventful recovery, and severe sometimes progressing to cell necrosis and death. Seventy-five percent of cases of acute pancreatitis fall into this mild category. The incidence of acute pancreatitis ranges from 54 to 238 episodes per 1 million per year (Levelle-Jones & Neoptolemos, 1990). About half the patients with acute pancreatitis are older than 60 years, and among them there is a slightly higher prevalence in women, probably caused by a higher incidence of gallstone-associated pancreatitis (Gullo et al, 1994). Histologically, acute pancreatitis is characterized by a wide spectrum of lesions, including edema, fatty necrosis, parenchymal necrosis, and hemorrhage.

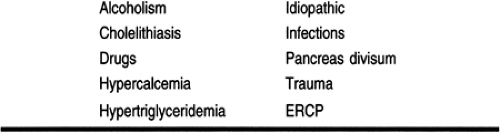

There are many causes of acute pancreatitis (Table 28-1), but more than 80% of cases are caused by alcohol or gallstones. Another 10% of cases are idiopathic but might be related to the presence of biliary sludge (Lee et al, 1992). Other, rarer causes make up the final 10%.

History and Physical Examination

Clinically, abdominal pain and raised serum concentration of pancreatic enzymes are the most common features (Gullo et al, 1994). Signs and symptoms typically include sudden epigastric pain radiating to the back, associated with nausea and vomiting. The pain is severe and is aggravated by food and alleviated by leaning forward. The patient often moves about constantly in search of a comfortable position. There is often a history of alcohol excess, and the degree of alcohol consumption must be explored if there is no suggestion of cholelithiasis.

Physical findings of acute pancreatitis include fever, tachycardia, epigastric tenderness with guarding, and rebound tenderness, if severe. Bowel sounds are often diminished; absence of bowel sounds indicates paralytic ileus. Hypotension and tachypnea are indicative of severe pancreatitis, as are decreased breath sounds from pleural effusion. Rarely, there are ecchymoses on the flanks (Grey-Turner sign) or on the periumbilical region (Cullen’s sign).

Approximately half the patients with acute pancreatitis recover spontaneously, as the disease has a self-limiting nature. There is a 10% mortality rate, with death usually occurring during the initial or second episode rather than subsequent ones. The more severe forms, however, are characterized by

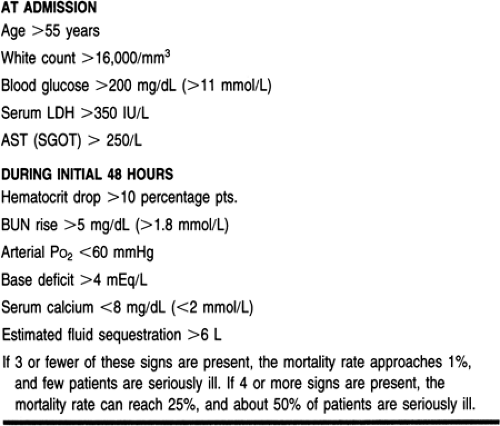

pancreatic necrosis, and the mortality rate increases to 20% or 30% (Kusske et al, 1996). Prognostic criteria for acute pancreatitis were developed by Ranson et al (1974) and are shown in Table 28-2.

pancreatic necrosis, and the mortality rate increases to 20% or 30% (Kusske et al, 1996). Prognostic criteria for acute pancreatitis were developed by Ranson et al (1974) and are shown in Table 28-2.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree