Introduction

Paediatric cardiorespiratory arrest is often caused by hypoxia, as the body has limited compensatory mechanisms to deal with severe illness or injury. Ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia is uncommon in children compared to adults, as primary heart disease occurs infrequently. Pronounced hypoxia arising from progressive illness (or the effects of injury) causes myocardial dysfunction, leading to profound bradycardia, which can degenerate to asystole or pulseless electrical activity (PEA). Other vital organs also suffer from severe hypoxia. Both asystole and PEA have poor outcomes.

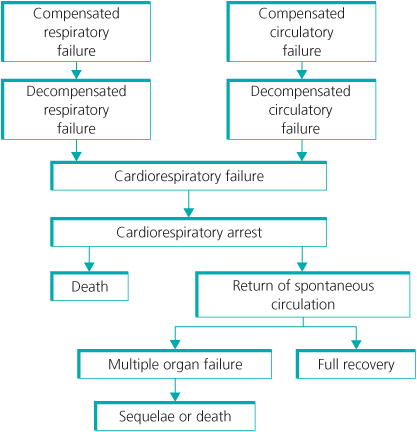

The body’s initial response is to adapt by altering respiratory or circulatory parameters, depending on the underlying condition, for example respiratory disease such as asthma will lead to changes in respiratory parameters which may lead in turn to changes in the circulation. If the body is unable to deal with the illness/injury, the compensatory changes may not be sustainable, leading to decompensated respiratory and/or circulatory failure (Figure 9.1).

Figure 9.1 The sequence of events in the seriously ill/injured child who deteriorates over time (with permission from Resuscitation Council UK).

These may combine as the body’s physiological responses further decline, leading to cardiorespiratory failure and, if unchecked, cardiorespiratory arrest.

Morbidity and mortality remain high if cardiorespiratory arrest occurs, as the profound hypoxia leads to multi-organ failure in many cases. For cardiorespiratory arrests that occur out of hospital, survival is between 6 and 12%, with fewer than 5% having no neurological consequences. In hospital, 27% of cardiac arrest patients survive to discharge, and of those having a respiratory arrest where cardiac output is still maintained, more than 70% have good long-term outcomes.

These figures highlight the importance of recognising the symptoms and signs of the body’s physiological responses to illness or injury as early as possible, as interventions can reverse the deterioration to cardiorespiratory arrest.

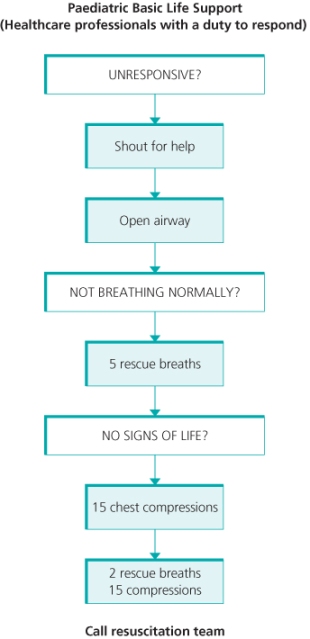

Paediatric basic life support

Treatment should follow the sequence—Airway, Breathing Circulation. There are differences from adult practice as the most common cause of cardiorespiratory arrest is hypoxia, hence the need to deliver oxygen from the outset. The key steps are outlined in the paediatric basic life support algorithm (Figure 9.2). This guidance is aimed predominantly at those with a duty to respond to paediatric emergencies. For those with no paediatric training or who have forgotten, or are unsure of, the correct paediatric sequence; it is perfectly acceptable, and far better than doing nothing, to use the adult sequence (see Chapter 4).

Figure 9.2 Paediatric basic life support algorithm. Reproduced with the kind permission of the Resuscitation Council (UK).

Unresponsive?

After confirming there are no dangers, the first stage is to confirm unresponsiveness. This may be done by gentle stimulation of the infant/young children, saying ‘Are you alright?’ and observing for any response, such as movement or breathing.

Should the child be unconscious but have a regular breathing pattern, it may be best to place them in the recovery position if there are no signs of trauma.

Shout for help

If there is no response, then shout for help. If someone comes to your aid, ask them to alert emergency services, telling them to give: the location of the child, the child’s approximate age and that basic life support is being given. Tell the person to return to you after they have done this.

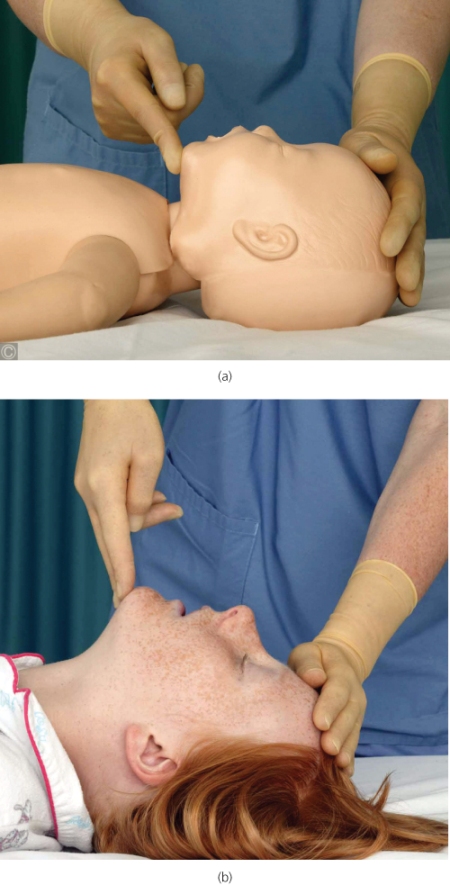

Open the airway

Open the airway by performing a head tilt, chin lift technique (Figure 9.3). Look inside the mouth to see if there is any foreign body that can be directly extracted. Look for chest wall movement, listen for any spontaneous breathing and feel if there is expired air on your cheek for no more than 10 seconds. If normal breathing is absent, you will have to deliver 5 rescue breaths.

Figure 9.3 Head tilt and chin lift in (a) an infant and (b) a child. Photograph reproduced with kind permission by Michael Scott and the Resuscitation Council (UK).

Irregular gasping (agonal) breaths are not normal and rescue breathing should be performed.

Five rescue breaths

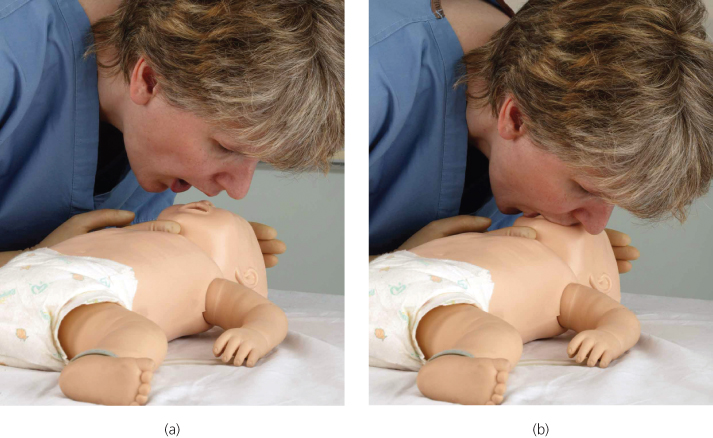

To deliver rescue breaths, put your mouth over the child’s, pinch the nose to occlude it and blow slowly (over about 1 to 1.5 s) in order to make the child’s chest rise as for a normal breath. For an infant, it may be easier to put your mouth on their face so that both the mouth and nose is covered (Figure 9.4). Look for chest wall movement to ensure the chest gently rises and falls with each breath you deliver. If the chest wall does not move, re-position the head, before performing the next breath in the sequence, as the airway may not be open.

Figure 9.4 (a) and (b) Mouth to nose ventilation in an infant. Photograph reproduced with kind permission by Michael Scott and the Resuscitation Council (UK).

No signs of life?

Then assess for signs of a circulation. This should take no more than 10 s. Look for signs of life (e.g. movement or regular breathing) and feel for a pulse. In an infant, feel for a pulse in a brachial artery, and in the older child, the carotid artery. In both age groups, a femoral artery may be palpated. Palpation of the pulse cannot be the sole determinant of the need for chest compressions.

If you are sure there are signs of life or a pulse of >60 beats min−1, continue giving breaths until the child/infant starts breathing regularly, when he should be turned into the lateral recovery position.

Chest compressions

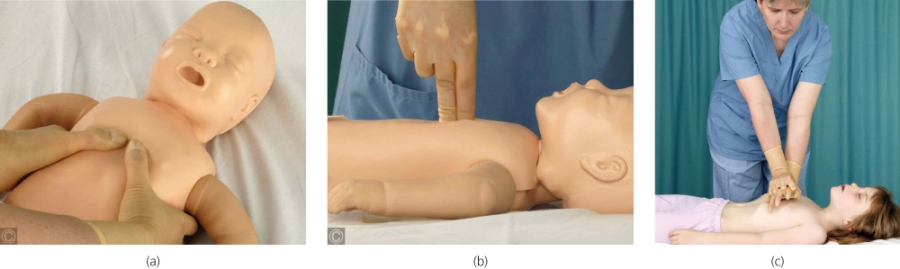

If there are no signs of life or a pulse of >60 min−1, or you are not sure, the next stage is to deliver 15 chest compressions. In the infant, if there are two rescuers, the infant’s thorax may be encircled by the rescuer’s hands, and the two thumbs used to deliver compressions, allowing the other rescuer to give the rescue breaths. A single rescuer may find it easier to use 2 fingers of one hand. In children, one or two hands should be used to achieve the correct compression depth (Figure 9.5).

Figure 9.5 Chest compression in an infant with (a) a two-thumb encircling technique, (b) a two-finger technique and (c) in a child with a two-handed technique. Photograph reproduced with kind permission by Michael Scott and the Resuscitation Council (UK).