HEADREST

A headrest for head and neck surgery can be fashioned from foam packing material (Styrofoam) or a piece of foam cushion or mattress. Use a 25 cm × 25 cm × 10 cm piece and hollow out the middle so that it is only one-third of the original depth. This space is for the patient’s head. The foam material will provide traction to keep it in place on the operating room (OR) table.1 This headrest can also be used as a sleeping pillow if the individual needs, or wants, to be only on his or her back.

REGIONAL NERVE BLOCKS

Most of the regional nerve blocks useful for ear, nose, and throat (ENT) procedures are discussed in Chapter 26.

To relieve most or all orofacial pain in adults, use a simple paravertebral block. This is an extremely safe procedure, because the injection is made with a 1.5-inch-long, 25-gauge needle. Inject 1.5 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine into the paravertebral musculature on both sides, 1 inch lateral to the seventh cervical spinous process. Bupivacaine provides good pain relief within 15 minutes for adults with toothache (odontalgia), mandibular fractures and dislocations, temporomandibular joint (TMJ) syndrome, ocular pain, facial pain from a variety of other causes, and headaches.2,3

EAR

If an otoscope is not available, use an ophthalmoscope to look through any type of speculum into the ear canal. Objects that can substitute for a speculum include a pen casing (cut the tapered point off a little and smooth it), a 1-cc syringe barrel with the end cut off and smoothed, a nasal speculum (be careful not to put it in too far), and similar objects. Note that many late-19th century otoscopes looked no different than modern nasal speculums. They used a direct or an indirect (head mirror) light source.4

Knowing how to remove foreign bodies from an ear can save time and resources. There is no evidence to support choosing one method over another in most cases, and many different techniques are available. It is also useful to know which cases may need to go to the OR to have foreign bodies removed under sedation. The most difficult foreign bodies to remove are spherical objects, those in contact with the tympanic membrane (TM), and those that have been in the ear for >24 hours.5 Most foreign bodies can be removed using irrigation, dissolution, suction, glue, or by other physical means. The removal of insects and metal objects requires special techniques.

Current sedation techniques (see the “Procedural Sedation” section in Chapter 16) make it safe to administer sedation to both adults and children before undertaking what may be painful or prolonged attempts at foreign-body removal. Anesthetizing the ear can gain the patient’s cooperation, although good anesthesia in the ear canal is difficult to achieve. Topical anesthetic can be dropped into the canal (if the foreign body is neither vegetable matter nor a button battery), although it usually has only a modest effect.

Irrigation is the least traumatic way to remove cerumen and smaller foreign bodies that are close to the TM. If the TM is not perforated, irrigate the ear with clean water at body temperature. (Cold water produces emesis.) For earwax, it may help to put in a softening agent for a few days before attempting irrigation.

Use a small piece of tubing connected to a syringe; a plastic intravenous (IV) catheter or the tubing from a butterfly cannula—with the needle cut off—works well. An alternative is to use a bulb syringe or a turkey baster. With both, low-pressure volume, rather than a directed stream of water, works best. Other successful improvisations have included oral jet irrigators (this may have too high a pressure, depending on the state of the batteries),6 a recreational water gun,7 and mouthfuls of water instilled (by the patient’s nurse-wife) through a cocktail straw.8 Aim the fluid stream at the superior aspect of the ear and, if possible, pulse the fluid for best results. Alternatively, direct the stream along the wall of the ear canal and around the object, flushing it out.

Do not irrigate the ear to remove hygroscopic objects, such as vegetables, beans, and other food matter, because these may swell. Also, do not irrigate button batteries that are more common in noses than in ears, because it only accelerates the tissue necrosis. Also, avoid nasal and otic drops in these patients.

Styrofoam is a common foreign body found in the ear. It is often compressed and tightly impacted in the ear canal. The friable substance tends to fragment if grabbed with forceps. The best removal method is to instill acetone or ethyl chloride, both organic solvents. This results in rapid and near-complete dissolution of the Styrofoam without any patient discomfort.9

Quickly remove objects that are light and will move easily with suction. Use a small soft-rubber suction catheter (e.g., pediatric feeding tube), a standard metal suction tip (e.g., Frazier tip), or a specialized flexible tip. It takes 100 to 140 mm Hg (or higher) negative pressure to attach an object, so using your mouth to suck on a tube will not work.

Mechanically removing an object involves grabbing the object and pulling it out of the ear. Most commonly done with cerumen, it also works for other compressible objects when using tiny (alligator) forceps. Alligator forceps are best for grasping soft objects like cotton or paper, although they are rarely available in resource-poor settings.

To remove cerumen and small, visualized foreign bodies, fashion improvised cerumen spoons by bending the end of a paper clip into a very tiny “U” shape. Do not do this with your fingers—use pliers or a similar tool. This “spoon” can also be used for removing foreign bodies from the nose.10 If the foreign body is at all irregularly shaped and is not made of organic material, grasp it with any available forceps or hemostat and remove.

Metallic objects, such as the appropriately feared button batteries, can sometimes be removed from the ear using a magnetized screwdriver.11 (Borrow one from your maintenance staff.) Remove the batteries immediately to prevent corrosion or burns. A delay of only an hour or two, or a missed diagnosis of a battery in a nose or an ear, may lead to liquefactive necrosis extending deep into tissues. Do not crush the battery during removal. Avoid nasal and otic drops. These electrolyte-rich fluids enhance battery corrosion and leakage, the generation of an external current, and local injury. After removing the battery, irrigate the canal to remove any alkali residue.

If the object is dry and smooth, put a tiny amount of cyanoacrylate (Super Glue) on the wooden end of a tiny swab (e.g., Q-tip) and touch the object. It will dry in about 15 seconds and then both can be extracted. The danger is gluing the stick to the patient. If this happens, do not fret—remove it with acetone or simply wait several hours.12

Insects are a special case of organic foreign body. They are the most frequent ear foreign body in adults. Generally, they are alive, and often panic the patient because of both the pain and the noise they generate.

Kill the insect before attempting to remove it. Quickly drop in any liquid that will not injure the ear canal (e.g., mineral or cooking oil, lidocaine, liquid soap, alcohol, etc.) to kill the insect—and to restore the patient to relative calm. Plain water or normal saline usually is ineffective. Most insects die in less than 3 minutes after dropping liquid into the ear.13

Patients with edematous otitis externa need a method of getting the medication into the ear canal. This usually requires an ear wick. To improvise an ear wick, use thin ribbon gauze, impregnated at the bedside with antibiotic/anti-inflammatory ointment. This gauze can be removed by patients, is inexpensive, and requires fewer visits than when patients use standard ear wicks.14

Acetic acid (10% vinegar) is an amazing, nontoxic, inexpensive, and widely used preventive and treatment for most cases of external otitis. Scuba divers routinely use it. Mix one part acetic acid (vinegar) with nine parts water. Instill enough to fill the ear canal as often as needed. The only side effect is a streak of white where it drips out of the ear. Simply wipe it off. One caveat: Diabetic patients and individuals whose ear canals have swollen shut need additional treatment; the latter can be treated with this medication if an ear wick is inserted. While patients with diabetes may be able to temporize with acetic acid, they should also have the appropriate antibiotics or antifungals instilled, if these are available. A mixture of 50% rubbing alcohol, 25% white vinegar, and 25% distilled water can also be used for external otitis. This should only be used four times a day (qid).15

Clinicians may need to perform a myringotomy if the patient is in pain from otitis and no analgesic, decongestant, or antibiotic is available. If a myringotomy is necessary, nearly any local anesthetic drops will anesthetize the TM if you wait 10 minutes after instilling them. For example, use one spray of 10% lidocaine aerosol directed into the clear external meatus onto the tympanum.16 Another option is to put in one drop (only!) of 10% phenol. If phenol is used, start the procedure immediately, because the anesthetic effect lasts only 10 minutes. (Phenol also can anesthetize other areas, such as pilonidal cysts.) To do the myringotomy, insert an 18-gauge needle into the anterior-inferior part of the TM. To take a culture, attach a tuberculin (TB) syringe. Avoid puncturing the membrane posteriorly. (David Merrell, MD. Personal communication, October 2006.)

NOSE

Nose drops and washes are reasonably benign ways to make “stuffed up” patients feel better and, in some cases, to “clear the way” for other medications. If the commercial varieties are not available, there are a variety of recipes that patients can make at home.

Recipe #1: Mix 1/2 teaspoon salt in 8 oz warm water, and store the solution in an empty spray bottle. Make a new solution after 2 days.17,18

Recipe #2: Add 2 to 3 heaping teaspoons of table salt and 1 rounded teaspoon of baking soda to 1 quart of boiled tap or bottled water. Store it in a 1-quart glass jar. If the mixture is too strong, reduce the salt to 1 to 2 teaspoons. If the patient’s nose is dry, add 1 tablespoon of corn syrup to the mix. Stir or shake before each use and store in the refrigerator; mix a fresh batch weekly.

For adults, use two to three times daily. Instill with a bulb, ear, or medical syringe. Warm the solution to body temperature and have patients stand over the sink or in the shower as they squirt toward the back of each nostril. Avoid contaminating the stock solution. For children, instill three drops as often as necessary in each nostril while they are supine with their head turned to one side. Have them blow their nose after 1 minute or, for younger children, use a suction bulb to remove mucous.18

Using intranasal anesthetic gains a patient’s cooperation for any manipulation. Obtain good intranasal anesthesia in several ways. Use 1 to 3 sprays of 10% lidocaine aerosol in the nose. Or spray the nose with 2 to 3 mL 4% lidocaine plus 1 drop (0.05 mL) of 1:1000 epinephrine. Then pack the nose with gauze soaked in the same solution.16

To anesthetize the entire nasal cavity, hyperextend the head and pour 20 mL of 1.25% lidocaine with 0.25 mL of 1:1000 epinephrine into each nostril; allow it to remain there for 3 minutes. (Before instilling the liquid, warn the patient to close his or her glottis by forming but not saying a “ggg” sound while the liquid is in his or her nose.) The patient then blows his or her nose.16 A less traumatic method is to attach a standard face mask to a nebulizer containing the solution and have the patient breathe through the nose.19 A variation is to connect wall oxygen to an atomizer using oxygen tubing with a lateral hole cut in it. Intermittently occluding the hole with a fingertip produces a spray of lidocaine from the atomizer nozzle. Held at the nostril, the nozzle can deliver 2% lidocaine throughout inspiration and produce dense anesthesia of the airway from the nose to the trachea in less than 5 minutes.20

A nasal speculum provides an excellent view when examining the nose and is vital when doing procedures, including packing the nose for epistaxis or draining a septal hematoma. The problem is finding the right-size speculum when it is needed. There are at least two methods to improvise a speculum, depending on the available resources.

If disposable otoscope specula are available, simply snip off the end of one to get the size you need, put it on an otoscope, and you have a speculum adequate to examine the nose.21

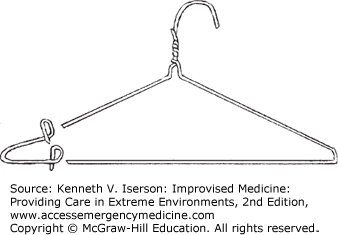

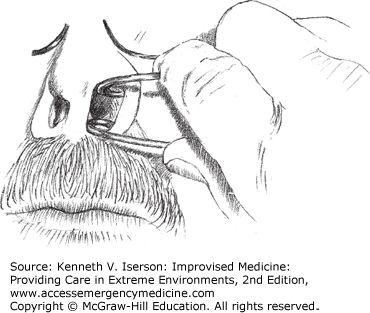

For a speculum that approximates the standard instrument, snip the corner off a wire hanger and bend the ends to the size you need (Fig. 28-1). Note that the loops bend inward so that the handle can be oriented toward the cheek (Fig. 28-2). Be careful to bend the V-shaped “corner” of the wire so that it exerts less pressure than you might need if making this into a self-retaining retractor.

Epistaxis is one of the most common complaints. It varies from a simple problem to a life-threatening event. Nasal bleeds are either anterior, posterior, or a combination of the two. While many clinicians use prepackaged materials to stop nasal bleeds, these are usually not available in austere situations.22

Adding a vasoconstrictor to an intranasal anesthetic stops up to 65% of anterior bleeds. A number of different, often readily available, anesthetics work well. Cocaine 4% is safe when used appropriately. Use a maximum of 200 mg (5 mL) or 2 to 3 mg/kg. Try to avoid using it in patients with coronary artery disease.22 Lidocaine 4% plus phenylephrine has an effect equivalent to that of cocaine.23 The maximum dose of lidocaine is 4 mg/kg. If using the injectable form, use up to 7 mg/kg lidocaine plus epinephrine. Tetracaine 1% plus 0.05% oxymetazoline (Afrin) works as well as lidocaine plus phenylephrine.24 It also lasts longer, up to 60 minutes. The maximum adult dose of tetracaine is 50 mg.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree