GYNECOLOGY

Contraceptive methods include medications, intrauterine devices (IUDs), surgery (e.g., vasectomy, tubal ligation, hysterectomy), spermicides, barriers (e.g., condoms), and “natural” methods. Only condoms protect against sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). Hysterectomies do not completely protect the patient, because Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae can still infect the urethra.

The so-called natural contraceptive methods are not very effective. However, without other means to control pregnancy, they have to be used. The methods include abstinence, withdrawal, breastfeeding, temperature measurement, mucous, and counting days (rhythm method).

Abstinence is hard to sustain and therefore does not work. Withdrawal is not much better, because the male often does not withdraw in time, or even know exactly when to withdraw. Breastfeeding often protects a woman from pregnancy in the first 6 months after delivery if she has not had menses, feeds the child nothing other than breast milk, and never goes more than 6 hours between breastfeedings. The temperature measurement method relies on keeping track of very small temperature changes over time, and so is unlikely to be useful in austere situations.

The mucous method requires the woman to check her vaginal mucous every day, at the same time, before she has intercourse. She wipes her vagina with a clean finger, paper, or cloth. If the mucous is clear, wet, and slippery, it means that she is fertile and should not have intercourse. If there is no mucous or if it is white, dry, and sticky, intercourse is probably safe two days later. If using this method, the woman should not douche or wash her vagina. The method is completely useless in the presence of vaginal infections.1

The counting days or rhythm method is somewhat effective for women with a regular menstrual cycle of 26 to 32 days. Counting from the first day of menstrual bleeding, she abstains from sex from the 8th day through the 19th day of her cycle. She can have sex again on the 20th day. Women should use a chart to mark these days or, as an alternative, a bead chain with different colors. Each bead designates 1 day. To make a bead chain, string 32 beads on a string in this order: 1 red bead followed by 6 blue beads, 12 white beads, and 13 more blue beads. Use a small string or rubber grommet to mark where she is in her cycle. The red bead marks the onset of menses. The 6 blue beads are “safe” days for sex, as are the other 13 blue beads. The white beads are her fertile days.2

Male and female condoms are both successful contraceptive methods, but they cannot be improvised. Buy them! They also have medical uses, as described elsewhere in this book (e.g., controlling postpartum hemorrhage, ultrasound probe covers, and improvised esophageal stethoscopes).

Even in austere circumstances, emergency contraception may be an important issue. The medication of choice after unprotected sexual intercourse (UPSI) is levonorgestrel (LNG), which is now widely available. Table 31-1 lists specific indications for this treatment. It should be given as a single 1.5-mg dose as soon as possible and, for the most efficacy, within 72 hours. If the woman can tolerate only a 0.75-mg dose of the drug, repeat it in 12 hours.

| Normal Contraceptive Method | Indications for Emergency Contraception |

|---|---|

| Combined pills (21 active tablets) | If three or more 30-35 mcg EE or if two or more 20 mcg EE pillshave been missed in the first week of pill taking (i.e., days 1-7) and UPSI occurred in week 1 or in the pill-free week. |

| POP | If one or more POPs have been missed or taken >3 hours late and UPSI has occurred in the subsequent 2 days. |

| Intrauterine contraception | If there has been complete or partial expulsion of the IUD, or ifit is removed at mid-cycle and UPSI has occurred in the last7 days. |

| Progestogen-only injectables | If the contraceptive injection is late (>14 weeks from the previous injection for medroxyprogesterone acetate or >10 weeks for norethisterone enanthate) and UPSI has occurred. |

| Barrier | If there has been failure of a barrier method. |

The alternatives are to use birth control pills with adequate doses of ethinyl estradiol (EE) and LNG within the first 120 hours after UPSI or to insert a copper-containing IUD within 5 days of UPSI. If combination birth control pills are used, the dose must be ≥100 micrograms (mcg) EE plus 0.50 mg LNG or 0.75 mg LNG alone. This means the woman will have to take between 2 and 20 pills at one time. She repeats the same dose 12 hours later. Taking diphenhydramine (Benadryl) or a similar medication 1 hour before the contraceptive markedly reduces the frequent incidence of emesis. If emesis occurs within 2 hours of taking the contraceptives, repeat the dose.3

Note that if the contraceptive contains norgestrel, it is only half as effective as LNG; double the dose. Women who are using liver enzyme-inducing drugs (e.g., some antiepileptics, antibiotics, St. John’s wort) must take between 2.25 and 3 mg of LNG. If necessary, women can use emergency contraception more than once during each menstrual cycle.

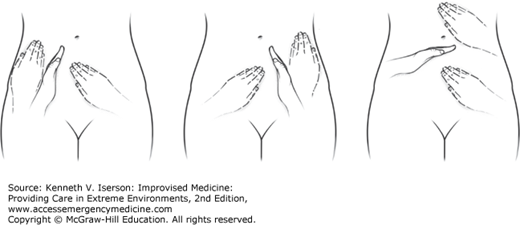

Differentiating intra-abdominal pain from pelvic pain can be challenging, especially when few imaging resources exist. Ming-Cheh Ou described a physical examination method that helps identify the source of abdominal pain in women with an acute abdomen. The procedure, shown in Fig. 31-1, uses the non-palpating hand to physically separate the “pelvic trapezoid” from the rest of the abdomen, while the other hand palpates on both sides of the barrier hand. If pain is found only within the trapezoid and absent outside of it, this indicates pelvic disease (Fig. 31-2). If the woman has definite pain outside the trapezoid and none or equivocal pain within, it is most likely abdominal pain. Diffuse pain within and outside the trapezoid can stem from multiple causes.5

When a vaginal speculum is not available or is not the right size to examine a patient, simply revert to what our forebears used: retraction. In austere circumstances, clinicians still fashion vaginal retractors from spoons, surgical retractors, or even barbecue tongs. (Col. Patricia R Hastings, AMEDDCS. Personal communication, April 9, 2007.) Using these instruments does, however, require an assistant to hold the posterior retractor while the examiner elevates the anterior vagina with another retractor. The only additional requirement is a light source; use a headlamp, if available.

In small girls, use test tubes of varying sizes to examine the vagina, although procedures cannot be done with this method.

In austere situations, syndromic treatment of STDs is the best approach to this common problem. (See the “Tests for Sexually Transmitted Diseases” section in Chapter 35.)

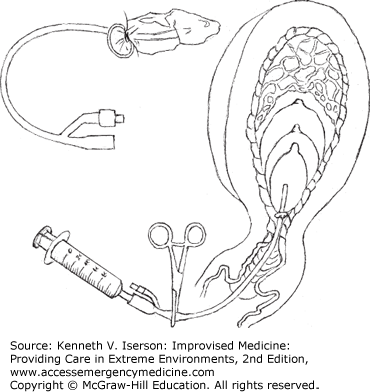

Easily treat a Bartholin’s gland abscess with a small stab incision (not large enough for the catheter to fall out) and the placement of a short Word catheter. However, Word catheters are unlikely to be available in austere settings. An alternative is to use a balloon urethral catheter and run the catheter down the leg, with a gauze or plastic bag over the end to catch any pus that drains. Use an 8- or a 10-Fr pediatric catheter, if available, because they are shorter. Do not cut the catheter; it destroys the balloon port. Patients, however, do not like having this extra appendage hanging down for the time it takes to heal with a fistula.

So, make a generally acceptable alternative with a few modifications to the catheter. Once the pediatric catheter balloon is in the abscess, clamp it with a hemostat. Slowly inflate the balloon with 3 to 4 mL of saline or sterile water (do not overinflate it and cause pain), and firmly clamp the catheter with a hemostat several centimeters distal to the balloon. Then cut the catheter 2 cm distal to the clamp site to keep the balloon inflated. Using a tuberculin or insulin syringe, inject a generous amount of cyanoacrylate into the small balloon port in the remaining part of the catheter and squeeze it for a minute or so. After a few minutes, the adhesive hardens and you can remove the hemostat. The balloon will remain inflated due to the cyanoacrylate. The patient can return in 3 to 6 weeks to have the catheter removed by cutting the catheter proximal to the cyanoacrylate. The balloon deflates and the catheter drops out.6

There are two additional, simpler methods to modify the catheter: tying it off with a silk suture rather than occluding the balloon port with glue, or tying the catheter itself into a knot before cutting it short. Both work well in austere settings. Andy Norman, MD, tells the women to stick the end of the catheter into the vagina for comfort once it stops draining. This prevents it from getting caught on their clothes. (Personal communication, February 15, 2015.)

Remarkably, an improvised test may be nearly as good as cytology (Pap smear) for detecting high-grade cervical lesions (squamous intraepithelial lesions) or invasive cervical cancers. It may also be better than cytology for detecting moderate dysplasia. In resource-poor areas, the World Health Organization (WHO) suggests that clinicians use a “visual inspection with acetic acid” (VIA) and “visual inspection with Lugol’s iodine” (VILI) for detection of cervical dysplasia.

To do this, place the speculum without using gel. First do a VIA, applying 3% to 5% acetic acid (white vinegar) to the cervix with a cotton-tipped applicator. The vinegar may sting a little. After 1 minute, look for white patches. (The high-protein-content areas of premalignant and malignant cells coagulate and appear white when acetic acid is applied.) If they are there, it signifies a pathological lesion—which may be dysplasia, human papilloma virus, cervical cancer, or an STD. The test has a sensitivity of 56% and a specificity of 71% (positive predictive value 30%, negative predictive value 88%).

Then do a VILI by applying iodine to the cervix with a cotton-tipped applicator. If the entire cervix stains with iodine, it is a negative test; otherwise, it is positive. (Normal squamous cells are rich in glycogen that takes up iodine.) The test has a sensitivity of 87% and a specificity of 49% (positive predictive value 31%; negative predictive value 93%).7

These tests require no special magnification or tools. Patients who test positive should get further testing, if possible. If that is not possible and cryotherapy is available, use it. It is much less dangerous than letting untreated cervical cancer progress.8

Lacking equipment for colposcopy, gynecologists aboard the US Navy Ship (USNS) Comfort, on their Continuing Promise 2009 mission to Latin America, used eye loupes to provide sufficient magnification to view the cervix. (Commander Chris Reed, MD, USNS Comfort. Personal communication, June 3, 2009.)

Rarely encountered in industrialized countries, female circumcision comes in three forms: (a) partial or complete removal of the clitoris, (b) clitorectomy with removal of the labia minora, and (c) infibulation, the removal of the labia majora, labia minora, and clitoris with the vaginal opening sewed nearly closed. The last form causes most of the severe problems seen by health care workers. These include heavy vaginal bleeding, possibly with shock; infection (tetanus or wound infection initially, but human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] and hepatitis are common some time later); severe pain; and dysuria, urinary retention, or other urinary tract problems. Treatment is to stop the bleeding, treat pain and infection, and, if necessary, place a urethral catheter.

When a woman who has had an infibulation tries to deliver a child vaginally, problems can ensue. Be prepared to “deinfibulate” her by cutting through the scar.

The control of acute hemorrhage from the nonpregnant uterus can be difficult, because the cervical os may not be wide open. The hemorrhage may be due to a variety of sources, including gynecologic procedures. Historically, clinicians have used curettage to halt the bleeding; when this fails, hysterectomy has often been a last resort. However, it may be prudent to try mechanical methods first.

One method that stops acute, profuse uterine hemorrhage in most patients is to insert a balloon urethral (Foley) catheter into the uterine cavity. This requires no special expertise, equipment, or anesthesia. Once the catheter is in place, inflate the catheter balloon full enough with saline to tamponade the bleeding against the semi-rigid uterine wall. Leave the catheter in place from several hours to 2 days, depending on the etiology of the hemorrhage.9

As described in the “Postpartum Hemorrhage Control” section below in this chapter, if the uterine cavity is larger than normal, such as postpartum, tie a condom over the end of the catheter, then insert the catheter and inflate the condom, rather than the catheter (Fig. 31-3).

A hemorrhaging mass in the vagina is most likely cervical cancer. After placing a urethral catheter, pack the vagina to tamponade the bleeding. Placing sutures is generally futile and may make the bleeding worse.10

While surgical evacuation of the uterus takes special equipment, medical abortions do not. Most tested regimens use mifepristone or methotrexate plus misoprostol.

Using mifepristone, give 100 to 600 mg orally, followed in 6 to 72 hours by misoprostol 400 mcg orally or 800 mcg vaginally. Using methotrexate, give 50 mg/m2 intramuscularly (IM) or orally, followed by misoprostol 800 mcg vaginally in about 3 days. If the pregnancy persists 1 week after the methotrexate administration, give another dose of misoprostol.

With either regimen, if the pregnancy persists, a surgical abortion is indicated.11

OBSTETRICS

Approximately 15% of pregnant women develop complications that require special obstetric care, with up to 5% requiring surgery, including Cesarean sections (C-sections). Basic obstetric care includes the ability to assess the mother and fetus; do episiotomies; manage hemorrhage, infection, and eclampsia; deliver multiple births and breech presentations; use a vacuum extractor; and provide care for women after genital mutilation.12

An excellent online professional resource for routine and emergency obstetric care (with good illustrations) is WHO’s Managing Complications in Pregnancy and Childbirth: A Guide for Midwives and Doctors. Download it in any one of seven languages at www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/9241545879/en/.

Another excellent professional resource is from the Johns Hopkins Program for International Education in Gynecology and Obstetrics (JHPIEGO), Emergency Obstetric Care: Quick Reference Guide for Frontline Providers, which is available to download from the USAID website: http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/pnacy580.pdf.

Diagnosing pregnancy without a human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) level relies on signs and symptoms, some of which can be quite nebulous. The only three physical findings of pregnancy that most clinicians can rely on are palpating the enlarged uterus, hearing the fetal heartbeat, and seeing the baby in the birth canal. If HCG test strips are available, use either urine or serum. Whole blood may also work (see Chapter 20).

If you really must have laboratory test results to diagnose pregnancy in austere circumstances, use the frog test, which is much easier than the fabled rabbit test. The test, which uses a male frog (the common North American frog, Rana pipiens), is simple, rapid, and inexpensive. Inject 1 mL of the patient’s early-morning, concentrated urine sample (or blood serum obtained at any time) into the frog’s dorsal lymph sacs (back area behind the head). Blood serum is preferable, because it can be obtained any time and is less likely to cause toxic deaths in the frogs. Using a microscope, examine the frog’s urine at 30-minute intervals for 3 hours. If the test is positive, the frog will have spermatozoa in its urine. During the summer, the accuracy of the test decreases, but partially compensate for this by refrigerating the frogs.13

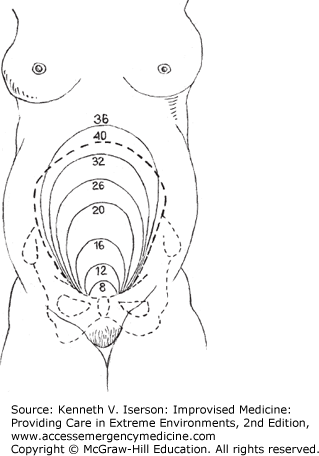

Without ultrasound to date the pregnancy, you must use the less-reliable method of counting from the patient’s last menses. One way to get the due date is to add 9 months and 7 days from the onset of the patient’s last period. For those using lunar time for measurements rather than a calendar, and assuming that the woman’s cycles are “1 moon” (4 weeks) apart, the due date would be “10 moons” after the onset of the patient’s last menses.

Once the fundus is palpable, the gestational age is closely related to the fundal height (Fig. 31-4).

Use any hollow tube made from wood, bamboo, plastic, clay, or metal as a fetoscope. The optimal size is a piece about 15 cm long, with a hollow core 3 to 4 cm in diameter.14,15

Counting the fetal heart rate with a stethoscope or Doppler is accurate and has good interobserver reliability.16 Skilled practitioners can often hear the baby’s heartbeat by the seventh or eighth month just by putting their ear to the patient’s belly in a quiet room. However, the heartbeat is easier to hear with a stethoscope or a fetoscope. (For improvised stethoscopes, see Chapter 5.)

If the baby’s heartbeat is heard best below the umbilicus, the baby is probably in the head-down position. If it is heard best above the umbilicus, the baby is most likely head-up (breech).

Non-pharmacological treatment includes locally applied heat and cold. Heat can be applied as a hot water bottle, a hot bath, or a microwaved wheat pillow (see the “Heating the Bed” section in Chapter 5). Locally applied ice packs often work well for headaches. If non-pharmacological treatment is ineffective, consider using local anesthetic infiltration or regional anesthetic blocks, depending on the location of the pain. If those do not work or if they are not applicable, use acetaminophen 1 g q6hr.17

If a woman passes tissue during her first trimester and the os has closed again, check her vital signs and, if normal, send her home. Tell her to return if there is increased bleeding or any sign of infection.

If she is spotting, reassure her that most pregnancies with only spotting go to term without difficulty. Check her vital signs; if normal, send her home.

If she has been bleeding and the os is open, she has an incomplete or inevitable miscarriage. She can wait for passage of more tissue and for the os to close. If the os remains open, she will need the products of conception removed.

If vaginal bleeding occurs after a miscarriage, delivery, or abortion, and a speculum or forceps is not available, use a sterile- or clean-gloved hand to feel the cervical os. Check for products of conception that are not permitting the os to contract. If necessary, use a non-gloved, but clean, hand. If material seems to be at the os, but it is too slippery to hold, use sterile gauze or a cloth boiled in water wrapped around your fingers to try to grasp and remove the tissue.

Simple tests can help to determine a pregnant woman’s well-being.

Checking her weight may be the most difficult test to improvise without a scale. However, other observations, such as her overall body habitus (e.g., extremely thin or fat face), may help a little. You are trying to determine whether the woman is too thin due to parasites, HIV, drug use, hyperemesis, or lack of food. She should gain at least 20 lb (9 kg) during the pregnancy. You also want to be sure that she has not gained >42 lb (19 kg) during the pregnancy, or >3 lb (1.5 kg) a week or 8 lb (3 kg) in a month, especially during the last 2 months of pregnancy. If she has gained too much weight, check her for diabetes, preeclampsia, or twins.

Check the mother’s vital signs. (See Chapter 7 for ways to improvise these tests.) If her blood pressure (BP) is >140/90 mm Hg, beware of preeclampsia. Also, check for very brisk reflexes (clonus) and for peripheral edema, especially in the hands and face.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree