Inflammatory Bowel Disease

James F. Marion MD

Catherine M. Concert MS, RN, CS, FNP

Ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease are chronic inflammatory diseases of the bowel and share many demographic, epidemiologic, and clinical features. Because UC and Crohn’s disease lack any unique distinguishing features and can resemble many other diseases, there is considerable potential for misdiagnosis. The essential nature and etiology of these inflammatory bowel diseases are unknown; however, our understanding of the clinical patterns, immune dysfunction, environmental factors, and genetic predisposition underlying these conditions has increased considerably and has spurred the development of new therapies. The early recognition of these diseases and appropriate management can spare patients hospitalization and surgery. Primary care providers are invaluable members of the team caring for patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and can claim a leading role in early disease recognition and diagnosis, coordination of management among multiple specialties, prevention of disease recurrence, and cancer screening.

ANATOMY, PHYSIOLOGY, AND PATHOLOGY

Intensive investigation over the last 60 years has failed to produce a simple explanation of the pathophysiology of IBD. An infectious agent has eluded investigators, and searches for multiple candidate parasites, mycobacteria, viruses, and bacteria have proved futile.

There is strong evidence that immune cell dysfunction, especially T-cell activation, plays an important role in UC and Crohn’s disease. Activated T lymphocytes produce IL-2 (an inflammatory cytokine), which may play a role in the inflammatory cascade in which the activation of other T cells, B cells, and macrophages occurs. Macrophages, the first line of defense, present luminal antigens to the sensitized T cells and release a host of proinflammatory cytokines. The cytokines produced in the cascade amplify the inflammatory response by recruiting neutrophils and monocytes. The subsequent release of oxygen metabolites, proteases, and other inflammatory cytokines then produces macroscopic mucosal injury (Pullman & Doe, 1992). Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and other cytokines then perpetuate the inflammatory response. The enteric nervous system and neuropeptides such as somatostatin may also play a role in regulating or perpetuating the inflammatory cascade. Platelet dysfunction and coagulation abnormalities, in close consort with the inflammatory cascade, are likely to contribute to the injury of the bowel.

Crohn’s Disease

Crohn’s disease is characterized by transmural granulomatous inflammation. It can involve any part of the gastrointestinal tract from the mouth to the anus but most commonly involves the terminal ileum (Crohn et al, 1932). Crohn’s disease can also be called regional enteritis, and when it involves the colon, granulomatous colitis. Inflammation tends to be patchy and noncontiguous; a mucosal biopsy taken during endoscopy may miss submucosal involvement. Colonic involvement typically spares the rectum.

Early in the inflammatory process, edema, hyperemia, and aphthous ulceration of the mucosa predominate. As the disease progresses, these aphthae can enlarge and coalesce to form deep, serpiginous ulcerations with nodular swelling of the intervening inflamed mucosal lining, producing the classic cobblestone appearance seen on contrast radiography. The bowel can then become thickened, fibrotic, and narrowed. The surrounding mesentery can also become edematous and fatty and can even encase the involved bowel segment, producing a phlegmon. A phlegmon or abscess can produce an abdominal mass palpable on physical examination. Fistulas, the result of transmural inflammation and fissuring, can penetrate the bowel wall, producing local perforation and abscess formation. These fistulas can communicate with adjacent bowel, organs (eg, urinary bladder), or even skin.

Ulcerative Colitis

The inflammatory process of UC involves only the colonic mucosa. The inflammation can involve the rectum and sigmoid colon or the entire colon. UC is usually symmetrical and continuous and involves the colon from the anal verge. Some patients present with isolated proctitis that can progress to involve the proximal colon. If the disease involves the entire colon (also called universal colitis) and the inflammation is severe, indirect injury of the terminal ileum, called backwash ileitis, can occur. Otherwise, any proximal gut or small bowel involvement implies Crohn’s disease.

Early inflammation can produce hyperemia, edema, and friability. As the inflammatory process progresses, spontaneous hemorrhage and superficial ulcerations of the mucosa develop. These can become diffuse and coalesce, forming deep, confluent ulcerations. With chronic recurrent injury, fibrosis can develop. Pseudopolyps, the result of chronic inflammation and healing, can protrude into the colonic lumen and cause obstruction. Longstanding inflammation can cause stricture formation, which can be a harbinger of underlying adenocarcinoma in patients with UC.

Severe inflammation causes thinning and dilation of the bowel wall and denudement of the mucosal lining, compromising the protective mucosal barrier. Toxic dilation, also called megacolon, can occur and possibly lead to perforation. Small rectovaginal or perirectal fistulas are rare but can occur in UC.

These distinguishing features of Crohn’s disease and UC become less reliable with chronic or severe disease and after successful treatment. Healing of UC can be uneven or patchy. Use of rectal or topical medications can produce rectal sparing similar to Crohn’s colitis.

PATHOLOGY

The traditional histologic, pathognomonic feature of Crohn’s disease, the noncaseating epithelioid granuloma, is found in only 10% to 28% of endoscopic biopsies and only half of surgical specimens. As disease severity increases, and with multiple biopsies, this yield is greater (Surawica et al, 1981). The inflammatory process can traverse all four layers of the bowel, up to and including the serosal layer.

The typical histologic feature of UC is the crypt abscess with proliferation of neutrophils in the lamina propria. Distortion or atrophy of the crypts with a villous or irregular mucosal surface can also be seen. These histologic changes can even be seen in endoscopically normal-appearing mucosa (Spiliadis & Lennard-Jones, 1987).

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The incidence of Crohn’s disease has been increasing over the last 50 years, whereas that of UC has remained stable (Whelan, 1990). UC is more prevalent than Crohn’s disease. UC has an incidence of approximately 6 to 8 cases per 100,000 population. The prevalence rate ranges from approximately 39 to 117 per 100,000 population. The incidence of Crohn’s disease is approximately 2 cases per 100,000 population. The prevalence rate is approximately 28 to 106 per 100,000 population.

Both are diseases of young people, and a diagnosis of IBD is most likely to be made in patients in their teens and 20s. Men and women are roughly equally affected. Although these diseases can occur in any age group, a second peak of incidence has been documented in the seventh and eighth decades of life (Lashner et al, 1986; Sedlack et al, 1980). This second peak may be attributable to confusion of diverticulitis or mesenteric ischemia with IBD or, more likely, a result of more intense evaluation of elderly patients suspected of having IBD.

There is considerable geographic variation in the incidence of IBD. The incidence in developed countries increases in direct proportion to the distance from the equator, with Scandinavia, the United Kingdom, and North America having the highest incidence. In the Southern Hemisphere, Australia and South Africa have an increased incidence. Whites are more likely to have IBD than patients of Asian or African descent. IBD is more common among patients of Jewish heritage. The geographic variability in incidence among Jewish populations appears to mirror that of the general population. Migrants to areas of higher incidence subsequently exhibit a higher rate of IBD. Studies that have indicated a higher incidence among urban residents or among members of certain occupations are probably undermined by referral bias.

Genetic Factors

A genetic component is suspected in IBD. Although the concordance between monozygotic twins is significantly less than 100%, siblings of patients with IBD are 17 to 35 times more likely to have IBD than the general population. Investigators have begun to focus on HLA alleles on chromosome 6, which may be associated with genes involved in the production of the inflammatory cytokine TNF-α. An “IBD gene” has not been discovered, and any heritable component to IBD is likely to involve multiple genes.

Environmental Factors

Certain environmental factors contribute to the pathogenesis of IBD. Smoking is positively associated with Crohn’s disease, but in UC a negative association has been observed. An increased risk for IBD among users of oral contraceptives has not been confirmed.

Diet would seem a logical focus of investigation, but numerous studies examining diet and IBD have failed to demonstrate any dietary risk factors. Increased sugar intake among patients with Crohn’s disease is more likely a result than a cause. There is no consistent evidence that prenatal vitamin supplements, tonsillectomy, childhood vaccinations, early childhood hygiene, toothpaste use, psychosocial factors, and breast-feeding or bottle-feeding play any role in the etiology of IBD (Sachar et al, 1980).

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

There are no set diagnostic criteria for IBD. The diagnosis of Crohn’s disease is based on the history and clinical profile and supporting radiographic, histologic, or endoscopic data. Most patients will give a history of at least 6 weeks of symptoms, thus excluding most acute infectious enterocolitides. Several conditions can act as impostors of Crohn’s disease, including tuberculosis, Yersinia enteritis, Entamoeba histolytica, and chlamydia. Appendicitis, intestinal lymphoma or carcinoma, carcinoid tumor of the small bowel, celiac sprue, and diverticulitis often can be mistaken for Crohn’s disease.

UC can be mistaken for several conditions that produce inflammation and ulceration of the colonic mucosa and bloody diarrhea: Escherichia coli, Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, E. histolytica, and cytomegalovirus. Other impostors include diverticulitis, cancer of the colon, ischemic colitis, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug colopathy, radiation injury to the rectum, pseudomembranous or antibiotic-associated colitis, and solitary rectal ulcer syndrome (Marion et al, 1998).

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

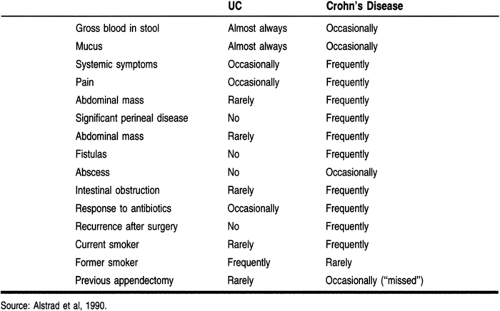

Patients with IBD can present with multiple, often confusing, symptoms. Certain patterns in the history of these patients allow the provider to distinguish IBD from other gastrointestinal diseases and between UC and Crohn’s disease (Table 27-1).

Crohn’s Disease

The patient with Crohn’s disease commonly presents with systemic symptoms, including malaise, fever, night sweats, and weight loss. Most commonly, patients complain of right lower

quadrant pain indicative of distal ileal involvement. Involvement of the stomach and duodenum can produce pain similar to that of peptic ulcer disease. As the disease progresses, chronic scarring can cause gastric outlet or duodenal obstruction.

quadrant pain indicative of distal ileal involvement. Involvement of the stomach and duodenum can produce pain similar to that of peptic ulcer disease. As the disease progresses, chronic scarring can cause gastric outlet or duodenal obstruction.

In the teenage patient, a history of developmental delay resulting from malabsorption may be elicited. Patients will often give a history of increased borborygmi. Nocturnal abdominal pain, severe enough to interrupt a sound sleep, or nocturnal bowel movements help to distinguish IBD from functional syndromes of the bowel. Gross rectal bleeding can be seen but is unusual. Most patients complain of frequent, loose, nonbloody stools and right lower quadrant pain.

Symptoms of intermittent small intestinal obstruction or a frank perforation may suggest underlying Crohn’s disease. Fistulas can penetrate adjoining abdominal or perineal structures such as the urinary bladder, producing pyuria, fecaluria, or pneumaturia. Penetration of the skin or vagina may present with passage of air, stool, or mucus. Complications, including toxic megacolon and colonic perforation, associated with UC can also be seen in Crohn’s disease. Patients may give a history of “missed” appendectomy—that is, ileitis that was mistaken for appendicitis.

Ulcerative Colitis

UC patients most often present with bloody stools accompanied by mucus and diarrhea. If only the rectum is inflamed, patients may complain of constipation with a sense of urgency and passage of bloody mucus. The passage of gross blood is the cardinal feature of UC. Disease limited to the distal or left colon is usually not accompanied by constitutional symptoms, whereas universal or more severe disease can produce symptoms of malaise, nausea, and diffuse abdominal pain. UC has a strong tendency toward recurrence, and patients may give a previous history of hospitalization for severe disease or toxic megacolon. A history of recent discontinuation of tobacco may also be elicited.

The primary provider may be faced with making the diagnosis of IBD in the pediatric patient. A child may present with severe, overt symptoms similar to those seen in adults, but often the provider is faced with a more subtle constellation of complaints, including unexplained fever, arthralgias, and growth retardation.

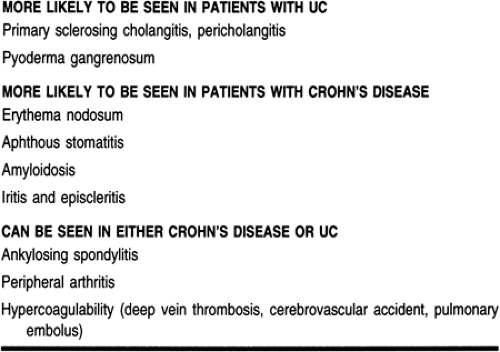

Extraintestinal manifestations occur in both UC an Crohn’s disease (Table 27-2). The arthritis affects the larger joints. Some manifestations may precede the bowel symptoms, and diagnosing IBD may be difficult. Other manifestations (eg, ankylosing spondylitis) are not related to the severity of the disease, and treatment is challenging.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree