Introduction

Patients and their relatives expect a prompt, effective response to in-hospital cardiac arrest. All clinical staff must be able to recognise the physiological and clinical signs of deterioration and respond promptly in the event of cardiac arrest occurring. Chapter 3 describes how to recognise a patient at risk of cardiac arrest and how to intervene in an attempt to prevent a cardiac arrest from occurring. If cardiac arrest has occurred, in most hospital settings (e.g. ward, clinics, operating theatres) clinical staff are expected to call for help and initiate resuscitation. Definitive care is then provided by a resuscitation team with staff trained and skilled in advanced life support (ALS) techniques.

Recognising cardiac arrest

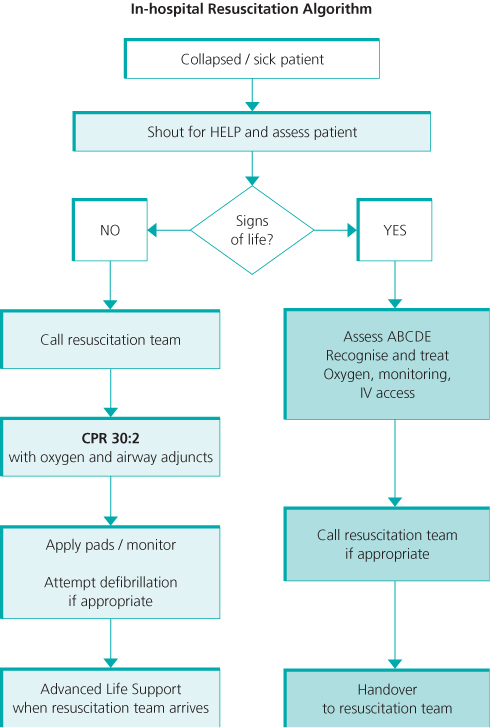

Assess the patient for a response: ask the patient, ‘Are you all right?’ If there is no response, gently shake their shoulders; if the patient does not respond, shout for help/activate the emergency call buzzer. Open the airway using the head tilt, chin lift manoeuvre. Keeping the airway open, look, listen and feel for normal breathing and other signs of life. If trained to do so, palpate the carotid pulse simultaneously (Figure 12.1). Take no more than 10 s to assess breathing/pulse. If the patient has no signs of life (confirmed by absence of normal breathing, coughing, purposeful movement), or there is doubt, start CPR and call the resuscitation team. Figure 12.2 summarises the sequence of steps for the initial assessment of the collapsed patient.

Figure 12.1 Confirming cardiac arrest by feeling for a carotid pulse and simultaneously checking for a pulse. Photograph reproduced with kind permission by Michael Scott and the Resuscitation Council (UK).

Figure 12.2 Initial sequence of steps for the assessment and treatment of the collapsed patient. Reproduced with the kind permission of the Resuscitation Council (UK).

Agonal breathing

Do not confuse agonal breathing, a brainstem response to hypoxia, with normal breathing. It is common in the early stages of cardiac arrest and should not be confused with signs of life. Agonal breathing may also start during CPR as cerebral perfusion improves, but it does not indicate return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC). Agonal breathing has a characteristic pattern (Box 12.1) and should be recognised as a sign of cardiac arrest.

- Barely breathing

- Heavy breathing

- Laboured breathing

- Problems breathing

- Noisy breathing

- Gasping breathing

Start resuscitation

Start resuscitation by delivering 30 high-quality chest compressions (Figure 12.3). Chest compressions should be to a depth of 5–6 cm, at a rate of 100–120 min−1. If performing CPR on a mattress, push deeper to compensate for compression of the underlying mattress. Allow full chest recoil between each chest compression. After 30 chest compressions, give 2 ventilations using a bag-mask or barrier device (Figure 12.4a and b). Add supplemental oxygen as soon as available. Continue sequences of 30 compressions to 2 ventilations. If there are delays in delivering ventilations, continue chest compressions alone until this can be rectified.

Figure 12.3 To deliver high-quality chest compressions, place the hands in the centre of the chest (between the nipples), compress the chest 5–6 cm in depth, at a rate of 100–120 min−1. Allow the chest to fully recoil between compressions. Photograph reproduced with kind permission by Michael Scott and the Resuscitation Council (UK).

Figure 12.4 After 30 compressions, provide 2 ventilations using (a) a barrier device or (b) bag-mask device. Photograph reproduced with kind permission by Michael Scott and the Resuscitation Council (UK).

Activate the emergency resuscitation team

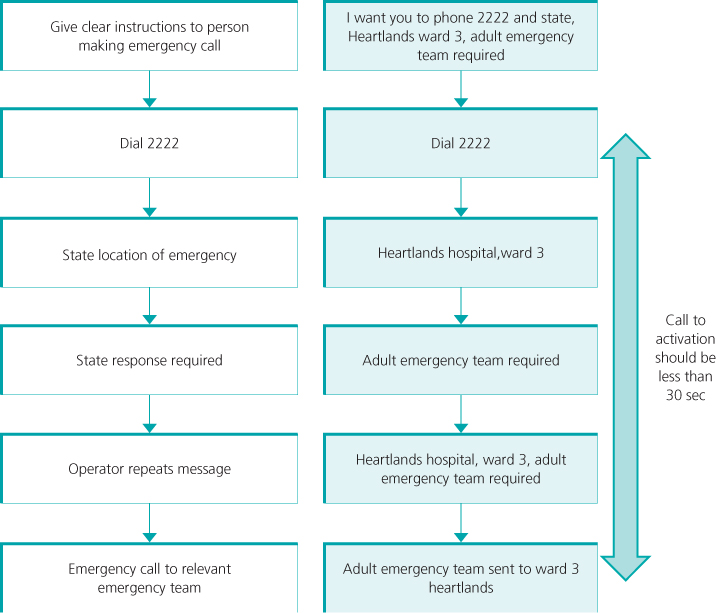

Once CPR is in progress, call for the resuscitation team. In the UK a standardised emergency telephone number is used—2222. This number is often also used to activate other emergency teams, for example trauma, paediatric, obstetric, neonatal, fire, security. Ensure that clear instructions are provided to the person who is sent to call the resuscitation team. Avoid the use of terms that may cause confusion such as ‘the patient has crashed’, ‘put out the call’, or ‘code blue’. Switchboard operators are not clinically trained and can respond only to the information provided by the caller. The person making the 2222 call must therefore state clearly the location of the emergency and the response required (Figure 12.5). Errors in communication are common and can lead to delays in activating the emergency team (Box 12.2).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>