Introduction

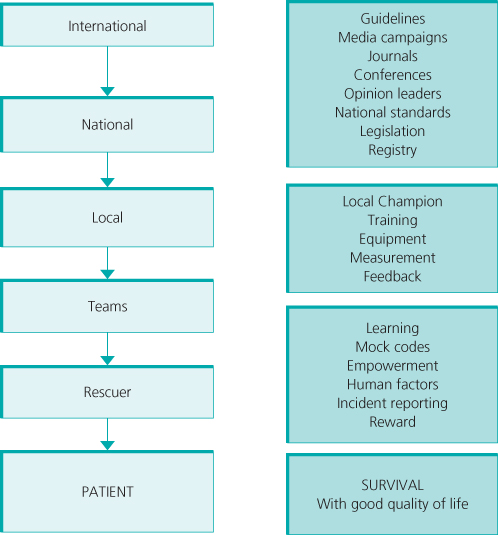

Improving outcomes from cardiac arrest requires high-quality care. Studies of both in- and out-of-hospital cardiac arrest show that there is a gap between what the guidelines say and what actually happens in clinical practice. The aims of high-quality care defined by the Institute of Medicine are that care has to be safe, effective, patient-centred, timely, efficient and equitable (Table 21.1). To achieve these aims, cardiac arrest care requires interventions at an international, national, local, team and individual rescuer level (Figure 21.1).

Table 21.1 Aims of high-quality care.

| Safe | Avoiding harm |

| Effective | Evidence based |

| Patient centred | Respectful care based on patient preferences, needs and values |

| Timely | Avoiding delays |

| Efficient | Avoiding waste |

| Equitable | Care quality does not vary according to issues such as race or socioeconomic status |

Data from Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century, 2001.

Measuring patient outcomes

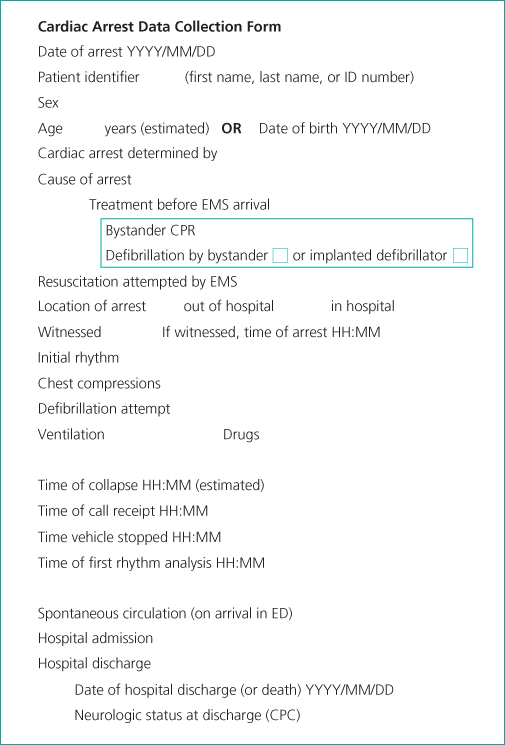

Continuous measurement of compliance with processes, and patient outcomes at a national and local level provides information on the impact of changes in practice, identifies areas for improvement, and also enables comparison in outcomes between different organisations. The Utstein style provides standardised definitions and reporting templates for cardiac arrest processes (Figure 21.2).

Several registries and epidemiological databases already exist and the number is rapidly increasing (Table 21.2). Specifically, at a local level, registries allow participating organisations to track their progress over time to assess whether they are improving and also how they compare with similar organisations. A network of organisations that has an infrastructure to reliably collect data in standardized manner also enables the conduct of large multi-centre research studies.

Table 21.2 Examples of cardiac arrest registries and epidemiological databases and some key findings.

| Details | In- or out-of hospital | Example of observations |

| American Heart Association Get With The Guidelines www.nrcpr.org Established 2000 | In-hospital | In-hospital cardiac arrest survival data for adults and children Observation that worse survival at night and weekends Racial differences in survival after cardiac arrest |

| CARES (Cardiac Arrest Registry to Enhance Survival)www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/cares.htm Established 2004 | Out-of-hospital | Outcome data Practice variation amongst emergency medicine systems |

| ROC (Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium Epistry) https://roc.uwctc.org/tiki/roc-public-home Established 2005 | Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest | Clinical trial network Variation in outcomes Effect of CPR-quality on outcomes Interventional studies |

| NCAA(National Cardiac Arrest Audit)https://ncaa.icnarc.org Established 2009 | In-hospital | Outcome data Comparative data Risk modelling |

The quality of life in those who survive to leave hospital seems to be good, but survivors can have ongoing, physical, psychiatric and cognitive problems. There is currently no consensus on the best way of assessing long-term outcomes in cardiac arrest survivors. The Cerebral Performance Category (CPC) score is most commonly used (Table 21.3). Survivors with a CPC score of 1 or 2 are usually said to have had a good neurological outcome. The CPC score is too crude, however, to describe more subtle problems that can occur in survivors.

Table 21.3 The Cerebral Performance Category (CPC) score.

| CPC | Definition |

| 1 | Good cerebral performance: conscious, alert, able to work, might have mild neurologic or psychological deficit |

| 2 | Moderate cerebral disability: conscious, sufficient cerebral function for independent activities of daily life. Able to work in sheltered environment |

| 3 | Severe cerebral disability: conscious, dependent on others for daily support because of impaired brain function. Ranges from ambulatory state to severe dementia or paralysis |

| 4 | Coma or vegetative state: any degree of coma without the presence of all brain death criteria. Unawareness, even if appears awake |

| 5 | Brain death: apnoea, areflexia, EEG silence, etc. |

Based on Safar P. Resuscitation after Brain Ischemia In Grenvik A and Safar P (eds), Brain Failure and Resuscitation, pp. 155–84, Churchill Livingstone, New York, 1981.

Patient safety incident reporting

Studies show that clinical staff and, in particular, doctors rarely report safety incidents.

Incident reports are important as they can help identify problems with implementation and areas for improvement both locally and at higher levels. Safety incidents or errors reported during CPR are associated with a decrease in survival from cardiac arrest. The most commonly reported errors to the US Get With The Guidelines registry were related to giving drugs, defibrillation, airway management and chest compressions. Reports to the Danish Patient Safety Database have identified problems with alerting the resuscitation team, human performance, missing or failing equipment and medication errors.

Education and implementation

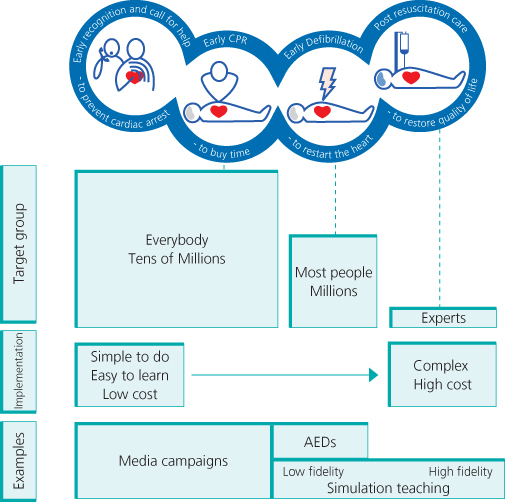

Survival from cardiac arrest is determined by the effectiveness of education and resources for implementation. The complexity of educational interventions needs to be based on how many people need to learn the intervention, the complexity of the intervention and how often it will be used by the learner (Figure 21.3). Training has to be tailored to meet the needs of different groups. Ideally all citizens should know how to do CPR. This will range from training lay people who will rarely need to do CPR, non-healthcare staff who work in roles that mean they have a duty of care (e.g. lifeguards) and healthcare staff. Even amongst healthcare staff, the level of training will vary according to their role – those involved in acute emergency care are most likely to deal with cardiac arrests. Numerous life support courses are available (see www.resus.org.uk). In the rest of this chapter we will discuss some emerging issues.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>