Introduction

In the year ending June 2009, there were just under one million incidents reported to the Department of Health by NHS facilities in England. Over 90% of these resulted in no harm or minimal harm to patients. However, on just under 70,000 occasions patients suffered significant harm; 7773 of these suffered permanent damage and 3735 people died.

Human factors (HF) are the environmental and behavioural elements that influence the way that people, or teams of people, interact with one another and the equipment and devices they use. In the analysis of healthcare critical incidents, they are found to play a causal role in 60–80% of cases. Extrapolating from the figures given here, these factors are likely to contribute to more than 2200 patient deaths each year.

Traditional resuscitation training used to focus on the factual knowledge and practical (technical) skills that are required to assess and treat the collapsed patient. There is now an increasing trend of instruction in HF within resuscitation courses and in general in the NHS as part of the patient safety agenda. It is against this background that this chapter has been included in this book.

A full discussion of HF is outside the scope of this book. The content is focused on three specific areas that are directly relevant to those attending and managing collapsed patients on an infrequent basis: how accidents occur, communication issues and the concept of situation awareness.

Nature of accidents

It is vital to recognise that we all make errors. Sometimes, even when multiple stops and checks have been put into place, things can still go wrong. On occasions, accidents may even occur as a consequence of the procedures put in place to prevent them.

The error chain

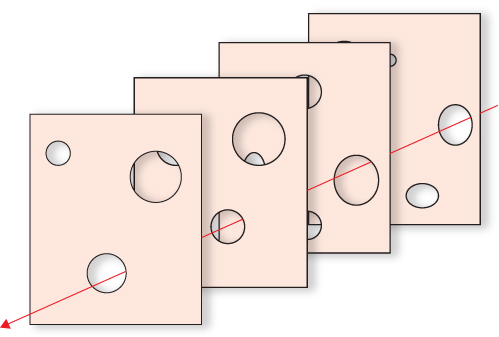

The key to recognising, understanding and preventing accidents is to understand that people do not seek to cause them. Bad or catastrophic events usually occur because a series of small errors or adverse circumstances that come together at a particular time and place. This creates a situation where the final error that triggers the accident is either inevitable or occurs through an action which seems entirely reasonable at the time. This concept, known as an error chain, was originally described by James Reason. It is also often referred to as ‘the Swiss cheese model’ and is shown in Figure 18.1.

Figure 18.1 James Reason’s Swiss cheese model of an error chain. (Reproduced from Reason J. Human error: models and management. BMJ. 2000 March 18; 320: 768–770, with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.)

Each layer of cheese represents a layer of defence such as a protocol, procedure or an environmental condition that serves to prevent an accident occurring. The holes represent the imperfections. When all the holes line up an accident occurs. Accidents can be prevented by identifying and plugging these holes. A clinical example of how this may be achieved is shown in Box 18.1.

At one trust it was noted that a number of incidents had occurred secondary to problems with emergency airway equipment. On closer examination it was found that the handles and the blades of the laryngoscopes on the affected trolleys were made by different manufacturers and were incompatible. The hole in the ‘physical’ layer was closed by standardising the type of laryngoscope used across the trust.

Note that this safeguard may still be overridden by a member of staff ordering an incorrect replacement for a used handle or blade. Preventing such behaviours depends in part on adequate training. However, good application of HF principles would also consider strategies to address softer factors, for example incorrect replacement orders may be placed when people are tired, distracted or unfocused for some other reason.

Individual fitness to work is a critical issue and is often poorly considered because of a desire not to let colleagues down. This has been recognized by the airline industry who introduced a personal self-screening checklist (IM SAFE) to highlight when a person should consider that they may not fit for work. This list is detailed in Table 18.1.

Table 18.1 IM SAFE checklist for fitness to work.

| Illness | Could my illness affect my performance at work? |

| Medication | Am I taking any medications that might affect my performance at work? |

| Stress | Am I stressed? Is it sufficient to draw me away from my focus at work? |

| Alcohol | Has the effects of last night worn off? Think before you drink! The night before an on-call is not the night to overindulge! |

| Fatigue | Have I had enough sleep recently? |

| Eating | Have I eaten appropriately to prepare me for a working day? |

In practice everyone needs to maintain vigilance for the presence of factors that might be seen as a hole in the cheese. They are often known as ‘Red Flags’ and they herald a weakening defence. When they are spotted it is vital they are shared with the team so that actions can be undertaken (or omitted) to prevent them becoming part of an error chain.

Communication

Issues around communication feature in almost every critical event. To understand why this occurs, it is useful to consider a simple model of communication like that shown in Table 18.2.

Table 18.2 Common situations and their effect on the communication process.

| Situation (stage of communication) | Consequence | Potential solutions |

| Channel: A noisy environment | The listener does not hear the speaker clearly. Missing or corrupted information may be guessed either consciously or unconsciously consequently distorting the meaning the speaker meant to convey. | Move to a quieter environment Avoid irrelevant conversations Utilise feedback |

| Channel & Encode/ Decode: Language barriers | One of the two speakers is not using their first language or messages are replayed through an interpreter | Use professional interpreters Utilise feedback |

| Encode/Decode: Mental Models Differ (see situation awareness below) | Meaning of spoken words are misinterpreted because the listener does not have the same information and experience as the speaker | Utilise Briefings Use structured communications Utilise feedback |

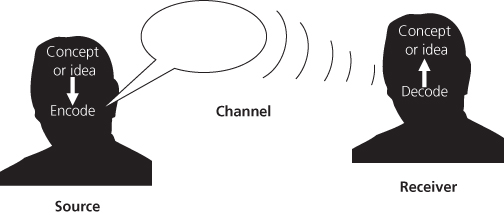

When we talk to one another we are trying to share or explore a concept or idea. On the part of the speaker (source) they have a model in their head of the issue being discussed and will base what they say on their view of that model (encoding). Their words pass from them, through a channel (room air or a telephone) to a listener (receiver) who will then interpret the words they hear and fit them into their own current model (decoding). Examples of how common situations can adversely affect this process are shown in Figure 18.2.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>