Hepatitis

Charlotte C. Cabello MSN, RN

At present, there are at least five well-known hepatotropic viruses: hepatitis A, B, C, D, and E. A new hepatotropic virus, hepatitis G, has also been identified. These viruses can cause inflammation of the liver with hepatocellular damage ranging from mild to severe to potentially fatal. The type of hepatitis virus and the degree of liver damage will determine the medical intervention needed. Patients with acute hepatitis should be monitored until liver function tests become normal. Cases of known exposure to hepatitis A and E should resolve quickly and spontaneously. Known exposure to hepatitis B and C viruses may require ongoing monitoring to detect and manage chronic disease. The goal is to maximize the level of functioning by minimizing the severity of the liver failure.

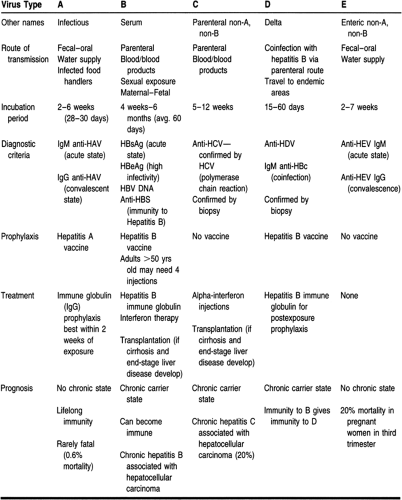

Other viruses can also cause inflammation of the liver, such as Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, rubella, herpes simplex, and varicella. For purposes of this chapter, the hepatotropic viruses will be reviewed (Table 26-1). Primary care providers must identify the virus causing liver damage, care for patients with these viral infections, and protect the community as well as themselves from exposure to these viruses.

HEPATITIS A (INFECTIOUS HEPATITIS)

Anatomy, Physiology, and Pathology

Hepatitis A is a single-stranded RNA virus of the enterovirus group. It is caused by the hepatitis A virus (HAV) and is primarily transmitted by the fecal–oral route. Transmission is facilitated by poor sanitation, intimate contact (household or sexual), and poor personal hygiene. Every year, outbreaks from water or food contaminated by infected food handlers are reported.

Epidemiology

The Centers for Disease Control reports that there are 75,000 to 100,000 cases of hepatitis A annually (Long & Kyllonen, 1997). Hepatitis A is a worldwide infection. It is nearly universal in childhood in overcrowded developing countries. It is thought that by adulthood, up to 50% of persons in the United States have been infected with HAV (Marx, 1993). Risk factors for infection with HAV include employment at day-care centers, international travel, intravenous drug use, and exposure to contaminated food or water.

History and Physical Examination

Symptoms consist of flu-like complaints. Jaundice may or may not appear. Other signs and symptoms of hepatitis can be found in Box 26-1. HAV is acute, self-limited, and rarely fulminant. Hepatic failure occurs in approximately 0.1% of cases (Marx, 1993), with a mortality rate of 0.6%. There is no carrier state, and initial exposure confers lifelong immunity.

Approximately 42% of persons who acquire the infection have no identifiable risk factor (Long & Kyllonen, 1997). Persons infected with hepatitis A may be asymptomatic and still have the potential to transmit disease. The incubation period is about 2 to 6 weeks (average 28 to 30 days), with the highest concentration of HAV found during the 2 weeks before jaundice appears. It is during this period that the person is highly infectious. Although rare, HAV can be transmitted by blood transfusions if the donation is made in the prodromal phase of the infection.

Diagnostic Studies

Liver enzyme elevations, specifically alanine aminotransferase (ALT), are indicative of hepatocellular damage. HAV is confirmed by finding anti-HAV IgM (specific antibody to the hepatitis A virus) in serum during the acute or early convalescent phase of illness. This antibody to HAV usually lasts 6 to 12 months. IgG (immunoglobulin G) remains detectable in the serum for a lifetime and denotes a convalescent infection.

Prophylaxis

Recently, a vaccine for hepatitis A has been developed. Immune globulin administered before exposure or during the incubation period of hepatitis A is protective against clinical illness. Its efficacy is greatest (80% to 90%) when given within 2 weeks of exposure (Jackson & McPherson, 1991). Anyone with a known exposure to hepatitis A should be tested for hepatitis A infection and if not immune should receive the vaccine as well as prophylactic immune globulin. Known IgG to hepatitis A means that the person has immunity to this infection and needs no prophylaxis. In cases of known exposure to hepatitis A, close family members of the infected person should also be offered the hepatitis A vaccine, as well as immune globulin as prophylaxis after they are tested for hepatitis A antibodies. For travelers to endemic countries, prophylactic administration of the hepatitis A vaccine plus a course of immune globulin before exposure is recommended.

Treatment Options, Expected Outcomes, and Comprehensive Management

Prevention of hepatitis A is enhanced by a clean water supply. This includes handwashing in restaurants and day-care centers. Use of cloth diapers would minimize the introduction of fecal

matter into landfills from disposable diapers. Universal enteric precautions are recommended for health care providers as they can care for potentially infectious asymptomatic patients. Outbreaks among health care workers show that inadequate handwashing and lack of appropriate glove use for handling stool result in exposure of health care workers to this virus.

matter into landfills from disposable diapers. Universal enteric precautions are recommended for health care providers as they can care for potentially infectious asymptomatic patients. Outbreaks among health care workers show that inadequate handwashing and lack of appropriate glove use for handling stool result in exposure of health care workers to this virus.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF HEPATITIS

During acute phases of any hepatitis infection, the patient may experience any or all of the following symptoms:

Loss of appetite

Nausea and vomiting

Low-grade fever

Malaise

Jaundice

Change in color of urine or stool

Right upper quadrant pain

Liver enlargement.

If these symptoms are vague in nature (eg, fatigue, loss of appetite), they may not be sufficient to alert the patient to visit the primary care provider.

Hepatitis A is a self-limiting disease. There currently is no treatment recommended for the disease itself, but symptomatic and supportive treatment should be given. These measures are discussed below in the section on self-care.

HEPATITIS B (SERUM HEPATITIS)

Anatomy, Physiology, and Pathology

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a DNA virus of the hepadnavirus family. It is transmitted parenterally, by sexual exposure, by contact with infected blood and tissues, and by maternal–fetal

spread. HBV codes for a variety of proteins. There are three distinct antigens: surface antigen (HBsAg), core antigen (HBcAg), and the e antigen (HBeAg). These three antigens have antibodies that may appear during the infectious phase.

spread. HBV codes for a variety of proteins. There are three distinct antigens: surface antigen (HBsAg), core antigen (HBcAg), and the e antigen (HBeAg). These three antigens have antibodies that may appear during the infectious phase.

Epidemiology

There are 1 to 1.25 million hepatitis B carriers in the United States. Hepatitis B is a major cause of death in the Far East and Africa (Bodenheimer et al, 1995). There are about 15,000 new cases of hepatitis B each year in the United States (Bodenheimer et al, 1995). HBV is prevalent in people born in endemic countries as well as their descendants. Most HBV-infected persons in the United States are intravenous drug users, homosexual men, and men and women with multiple sexual partners. Other at-risk groups are prison inmates, household contacts of HBV carriers, infants born to HBV-infected mothers, and hemodialysis recipients. Parenteral transmission can also occur from shared needles and tattooing. Health care workers are at risk through contact with blood and blood products and tissue. The worldwide immunization of newborns and infants with the hepatitis B vaccine should markedly decrease the incidence of hepatitis B in the future.

History and Physical Examination

The incubation period of hepatitis B is 4 weeks to 6 months, with an average of 60 days (Jackson & McPherson, 1991; Lisanti & Talotta, 1994). During the acute phase, symptoms may last about 4 months. Typically, patients with acute hepatitis B infection present with nonspecific complaints such as fatigue and anorexia. Jaundice may appear as the conjugated bilirubin level rises, and the patient may notice dark urine and clay-colored stool. Other signs and symptoms are noted in Box 26-1.

There is a 10% likelihood that persons who become infected with hepatitis B in adulthood will become chronic carriers (Vail, 1997). However, persons infected with hepatitis B in infancy have a 90% likelihood of becoming chronic carriers in adulthood (Vail, 1997). The risk of being a hepatitis B carrier is twofold: first, one can transmit the infection to others; second, one is at increased risk for the development of cirrhosis, liver failure, and primary liver cancer. Some chronic carriers are asymptomatic, whereas others experience symptoms that require intervention.

Diagnostic Studies

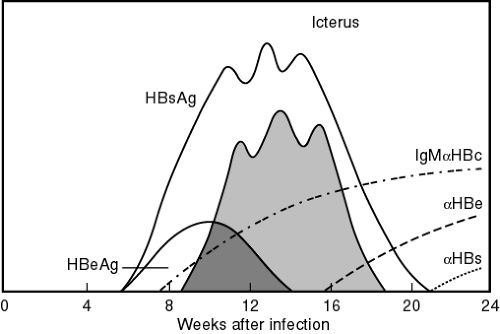

Nonspecific liver enzyme elevations (serum transaminase with alanine aminotransferase) may be the first indication that a patient has hepatitis. Clinical evidence of liver disease of at least 6 months’ duration, elevated serum aminotransferase levels with a liver biopsy showing an unresolved hepatic inflammation, and confirming serologic markers indicate chronic hepatitis B. HBsAg appears in the blood about 1 month after exposure and may remain for up to 6 months. Persistence of HBsAg for more than 6 months indicates a carrier or chronic state. The presence of hepatitis B core antibody (anti-HBc) occurs 2 weeks after HBsAg appears. The period between the disappearance of HBsAg and the appearance of hepatitis surface antibody (anti-HBs) is known as the window period. During the window period, the only serologic marker indicative of an acute hepatitis B infection is the presence of hepatitis B core IgM. The presence of anti-HBs indicates immunity to hepatitis B (Fig. 26-1).

Prophylaxis

There is a vaccine for hepatitis B that is 85% to 95% effective. It is a series of three injections, with the second dose given 1 month after the first and the third dose given 6 months thereafter. In adults older than age 50 who have low anti-HBs levels after three vaccine injections, a fourth injection is well tolerated and results in an improved immunogenic response (Bennett et al, 1996).

Recent changes in the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) mandates for health care workers have resulted in prophylactic vaccination of health care workers. This step, in combination with barrier protections, should minimize the risk of hepatitis B transmission to health care workers. There is controversy over the beneficial effects of immune globulin administration after needle stick exposure or contact with blood or blood products in cases of hepatitis B or C.

In the United States and worldwide, vaccination programs for all newborns and persons at high risk for contracting hepatitis B are underway in an attempt to decrease the morbidity and mortality rates from HBV. Family members of persons with acute hepatitis B should be treated with the hepatitis B vaccine as well as hepatitis B immune globulin.

Treatment Options, Expected Outcomes, and Comprehensive Management

There is no specific treatment for an acute hepatitis B infection. Rather, supportive care must be provided based on the symptoms. The section on self-care at the end of this chapter outlines supportive care measures.

Chronic hepatitis B carriers with active viral replication and well-compensated liver disease are good candidates for interferon therapy (Davis et al, 1995). Recommended treatment is

5 million units of interferon daily for 6 to 12 months (Schluger, 1997). The most common side effects of interferon therapy are neutropenia, which requires monitoring, and flu-like symptoms, which are transient and usually diminish with continued treatment. The success rate for interferon therapy is these cases is 25% to 50% (Vail, 1997).

5 million units of interferon daily for 6 to 12 months (Schluger, 1997). The most common side effects of interferon therapy are neutropenia, which requires monitoring, and flu-like symptoms, which are transient and usually diminish with continued treatment. The success rate for interferon therapy is these cases is 25% to 50% (Vail, 1997).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree