Key Concepts

In the absence of coexisting disease, resting systolic cardiac function seems to be preserved, even in octogenarians. Increased vagal tone and decreased sensitivity of adrenergic receptors lead to a decline in heart rate.

In the absence of coexisting disease, resting systolic cardiac function seems to be preserved, even in octogenarians. Increased vagal tone and decreased sensitivity of adrenergic receptors lead to a decline in heart rate.

Elderly patients undergoing echocardiographic evaluation for surgery have an increased incidence of diastolic dysfunction compared with younger patients.

Elderly patients undergoing echocardiographic evaluation for surgery have an increased incidence of diastolic dysfunction compared with younger patients.

Diminished cardiac reserve in many elderly patients may be manifested as exaggerated drops in blood pressure during induction of general anesthesia. A prolonged circulation time delays the onset of intravenous drugs, but speeds induction with inhalational agents.

Diminished cardiac reserve in many elderly patients may be manifested as exaggerated drops in blood pressure during induction of general anesthesia. A prolonged circulation time delays the onset of intravenous drugs, but speeds induction with inhalational agents.

Aging decreases elasticity of lung tissue, allowing overdistention of alveoli and collapse of small airways. Residual volume and the functional residual capacity increase with aging. Airway collapse increases residual volume and closing capacity. Even in normal persons, closing capacity exceeds functional residual capacity at age 45 years in the supine position and age 65 years in the sitting position.

Aging decreases elasticity of lung tissue, allowing overdistention of alveoli and collapse of small airways. Residual volume and the functional residual capacity increase with aging. Airway collapse increases residual volume and closing capacity. Even in normal persons, closing capacity exceeds functional residual capacity at age 45 years in the supine position and age 65 years in the sitting position.

The neuroendocrine response to stress seems to be largely preserved, or, at most, only slightly decreased in healthy elderly patients. Aging is associated with a decreasing response to β-adrenergic agents.

The neuroendocrine response to stress seems to be largely preserved, or, at most, only slightly decreased in healthy elderly patients. Aging is associated with a decreasing response to β-adrenergic agents.

Impairment of Na+ handling, concentrating ability, and diluting capacity predispose elderly patients to both dehydration and fluid overload.

Impairment of Na+ handling, concentrating ability, and diluting capacity predispose elderly patients to both dehydration and fluid overload.

Liver mass and hepatic blood flow decline with aging. Hepatic function declines in proportion to the decrease in liver mass.

Liver mass and hepatic blood flow decline with aging. Hepatic function declines in proportion to the decrease in liver mass.

Dosage requirements for local and general (minimum alveolar concentration) anesthetics are reduced. Administration of a given volume of epidural local anesthetic tends to result in more extensive spread in elderly patients. A longer duration of action should be expected from a spinal anesthetic.

Dosage requirements for local and general (minimum alveolar concentration) anesthetics are reduced. Administration of a given volume of epidural local anesthetic tends to result in more extensive spread in elderly patients. A longer duration of action should be expected from a spinal anesthetic.

Aging produces both pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes. Disease-related changes and wide variations among individuals in similar populations prevent convenient generalizations.

Aging produces both pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes. Disease-related changes and wide variations among individuals in similar populations prevent convenient generalizations.

Elderly patients display a lower dose requirement for propofol, etomidate, barbiturates, opioids, and benzodiazepines.

Elderly patients display a lower dose requirement for propofol, etomidate, barbiturates, opioids, and benzodiazepines.

Geriatric Anesthesia: Introduction

By the year 2040, persons aged 65 years or older are expected to comprise 24% of the population and account for 50% of health care expenditures. In Europe, persons aged 65 years or older are expected to comprise 30% of the population within the next 40 years. Of these individuals, many will require surgery. The elderly patient typically presents for surgery with multiple chronic medical conditions, in addition to the acute surgical illness. Age is not a contraindication to anesthesia and surgery; however, perioperative morbidity and mortality are greater in elderly than younger surgical patients.

As with pediatric patients, optimal anesthetic management of geriatric patients depends upon an understanding of the normal changes in physiology, anatomy, and response to pharmacological agents that accompany aging. In fact, there are many similarities between elderly and pediatric patients (Table 43-1). Individual genetic polymorphisms and lifestyle choices can modulate the inflammatory response, which contributes to the development of many systemic diseases. Consequently, chronologic age may not fully reflect an individual patient’s true physical condition. The relatively high frequency of serious physiological abnormalities in elderly patients demands a particularly careful preoperative evaluation.

|

Elderly patients are frequently treated with β-blockers. β-Blockers should be continued perioperatively, if patients are taking such medications chronically, to avoid the effects of β-blocker withdrawal. A careful review of patients’ often extensive medication lists can reveal the routine use of oral hypoglycemic agents, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, antiplatelet agents, statins, and anticoagulants. Because elderly patients frequently take multiple drugs for multiple conditions, they often benefit from an evaluation before the day of surgery, even when scheduled for outpatient surgery. Preoperative laboratory studies should be guided by patient condition and history. Patients who have cardiac stents requiring antiplatelet therapy present particularly vexing problems. Their management should be closely coordinated between the surgeon, cardiologist, and anesthesiologist. At no time should the anesthesia staff discontinue antiplatelet therapy without discussing the plan with the patient’s primary physicians.

Age-Related Anatomic & Physiological Changes

Cardiovascular diseases are more prevalent in the geriatric than general population. Still, it is important to distinguish between changes in physiology that normally accompany aging and the pathophysiology of diseases common in the geriatric population (Table 43-2). For example, atherosclerosis is pathological—it is not present in healthy elderly patients. On the other hand, a reduction in arterial elasticity caused by fibrosis of the media is part of the normal aging process. Changes in the cardiovascular system that accompany aging include decreased vascular and myocardial compliance and autonomic responsiveness. In addition to myocardial fibrosis, calcification of the valves can occur. Elderly patients with systolic murmurs should be suspected of having aortic stenosis.  However, in the absence of co-existing disease, resting systolic cardiac function seems to be preserved, even in octogenarians. Functional capacity of less than 4 metabolic equivalents (METS) is associated with potential adverse outcomes (see Table 21-2). Increased vagal tone and decreased sensitivity of adrenergic receptors lead to a decline in heart rate; maximal heart rate declines by approximately one beat per minute per year of age over 50. Fibrosis of the conduction system and loss of sinoatrial node cells increase the incidence of dysrhythmias, particularly atrial fibrillation and flutter. Preoperative risk assessment and evaluation of the patient with cardiac disease were previously reviewed in this text (see Chapters 18, 20, & 21). Age per se does not mandate any particular battery of tests or evaluative tools, although there is a long tradition of routinely requesting tests such as 12-lead electrocardiography (ECG) in patients who are older than a defined age. Nonetheless, elderly individuals are more likely to present for surgery with previously undetected conditions that require an intervention, such as arrhythmias, congestive heart failure, or myocardial ischemia. Cardiovascular evaluation should be guided by American Heart Association guidelines.

However, in the absence of co-existing disease, resting systolic cardiac function seems to be preserved, even in octogenarians. Functional capacity of less than 4 metabolic equivalents (METS) is associated with potential adverse outcomes (see Table 21-2). Increased vagal tone and decreased sensitivity of adrenergic receptors lead to a decline in heart rate; maximal heart rate declines by approximately one beat per minute per year of age over 50. Fibrosis of the conduction system and loss of sinoatrial node cells increase the incidence of dysrhythmias, particularly atrial fibrillation and flutter. Preoperative risk assessment and evaluation of the patient with cardiac disease were previously reviewed in this text (see Chapters 18, 20, & 21). Age per se does not mandate any particular battery of tests or evaluative tools, although there is a long tradition of routinely requesting tests such as 12-lead electrocardiography (ECG) in patients who are older than a defined age. Nonetheless, elderly individuals are more likely to present for surgery with previously undetected conditions that require an intervention, such as arrhythmias, congestive heart failure, or myocardial ischemia. Cardiovascular evaluation should be guided by American Heart Association guidelines.

| Normal Physiological Changes | Common Pathophysiology |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | |

|

|

| Respiratory | |

|

|

| Renal | |

|

|

Elderly patients undergoing echocardiographic evaluation for surgery have an increased incidence of diastolic dysfunction compared with younger patients. Diastolic dysfunction prevents the ventricle from relaxing and consequently inhibits diastolic ventricular filling at relatively low pressures. The ventricle becomes less compliant, and filling pressures are increased. Diastolic dysfunction is NOT equivalent to diastolic heart failure. In some patients, systolic ventricular function can be well preserved; however, the patient can have signs of congestion secondary to severe diastolic dysfunction. Diastolic heart failure most often coexists with systolic dysfunction.

Elderly patients undergoing echocardiographic evaluation for surgery have an increased incidence of diastolic dysfunction compared with younger patients. Diastolic dysfunction prevents the ventricle from relaxing and consequently inhibits diastolic ventricular filling at relatively low pressures. The ventricle becomes less compliant, and filling pressures are increased. Diastolic dysfunction is NOT equivalent to diastolic heart failure. In some patients, systolic ventricular function can be well preserved; however, the patient can have signs of congestion secondary to severe diastolic dysfunction. Diastolic heart failure most often coexists with systolic dysfunction.

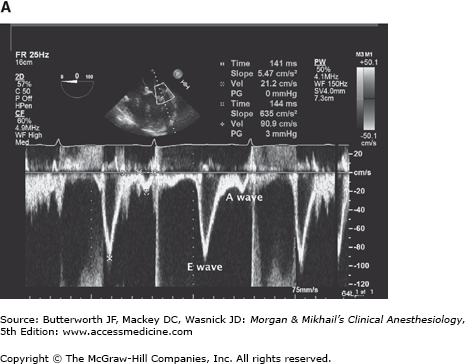

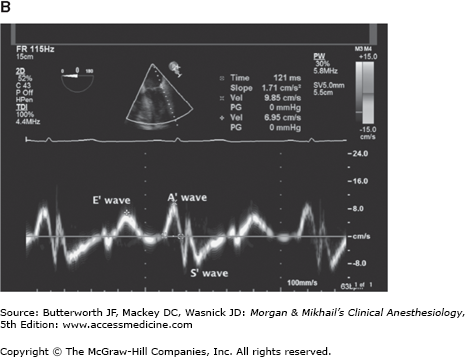

Echocardiography is used to assess diastolic dysfunction. A ratio of greater than 15 between the peak E velocity of transmitral diastolic filling and the E’ tissue Doppler wave is associated with elevated left ventricular end-diastolic pressure and diastolic dysfunction. Conversely, a ratio of less than 8 is consistent with normal diastolic function (see Figure 43-1).

Figure 43-1

A: In this Doppler study of diastolic inflow, the E wave is seen with a peak velocity of 90.9 cm/sec. This Doppler study reflects the velocity of blood as it fills the left ventricle early in diastole. B: In tissue Doppler, the velocity of the movement of the lateral annulus of the mitral valve is measured. The E’ wave in this image is 6.95 cm/sec. This corresponds to the movement of the myocardium during diastole. (Reproduced, with permission, from Wasnick J, Hillel Z, Kramer D, et al: Cardiac Anesthesia & Transesophageal Echocardiography, McGraw-Hill, 2011.)

Marked diastolic dysfunction may be seen with systemic hypertension, coronary artery disease, cardiomyopathies, and valvular heart disease, particularly aortic stenosis. Patients may be asymptomatic or complain of exercise intolerance, dyspnea, cough, or fatigue. Diastolic dysfunction results in relatively large increases in ventricular end-diastolic pressure, with small changes of left ventricular volume; the atrial contribution to ventricular filling becomes even more important than in younger patients. Atrial enlargement predisposes patients to atrial fibrillation and flutter. Patients are at increased risk of developing congestive heart failure. The elderly patient with diastolic dysfunction may poorly tolerate perioperative fluid administration, resulting in elevated left ventricular end-diastolic pressure and pulmonary congestion.

Diminished cardiac reserve in many elderly patients may be manifested as exaggerated drops in blood pressure during induction of general anesthesia. A prolonged circulation time delays the onset of intravenous drugs, but speeds induction with inhalational agents. Like infants, elderly patients have less ability to respond to hypovolemia, hypotension, or hypoxia with an increase in heart rate. Ultimately, cardiovascular diseases, including heart failure, stroke, arrhythmias, and hypertension contribute to an increased risk of morbidity, mortality, increased cost of care, and frailty in elderly patients.

Diminished cardiac reserve in many elderly patients may be manifested as exaggerated drops in blood pressure during induction of general anesthesia. A prolonged circulation time delays the onset of intravenous drugs, but speeds induction with inhalational agents. Like infants, elderly patients have less ability to respond to hypovolemia, hypotension, or hypoxia with an increase in heart rate. Ultimately, cardiovascular diseases, including heart failure, stroke, arrhythmias, and hypertension contribute to an increased risk of morbidity, mortality, increased cost of care, and frailty in elderly patients.

Research is ongoing into the relationship between telomere biology and cardiovascular disease. Telomeres, which are located at the chromosome terminus, protect the DNA from degradation during cell division. With each cell division, there is progressive telomere loss. Cells with short telomeres undergo “replicative senescence” and apoptosis. Telomerase maintains telomere length, but has low activity in human cells. Indeed, telomere length varies among humans based upon inheritance and environmental factors. Telomerase activity is deficient in various early aging syndromes. Telomere shortening may be either a cause or a consequence of cardiovascular disease. Whatever the exact mechanism of cardiovascular aging, patient management should at all times be in accordance with American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guidelines.

Aging decreases the elasticity of lung tissue, allowing overdistention of alveoli and collapse of small airways. Residual volume and the functional residual capacity increase with aging. Airway collapse increases residual volume and closing capacity Even in normal persons, closing capacity exceeds functional residual capacity at age 45 years in the supine position and age 65 years in the sitting position. When this happens, some airways close during part of normal tidal breathing, resulting in a mismatch of ventilation and perfusion. The additive effect of these emphysema-like changes decreases arterial oxygen tension by an average rate of 0.35 mm Hg per year; however, there is a wide range of arterial oxygen tensions in elderly preoperative patients. Both anatomic and physiological dead space increase. Other pulmonary effects of aging are summarized in Table 43-2.

Aging decreases the elasticity of lung tissue, allowing overdistention of alveoli and collapse of small airways. Residual volume and the functional residual capacity increase with aging. Airway collapse increases residual volume and closing capacity Even in normal persons, closing capacity exceeds functional residual capacity at age 45 years in the supine position and age 65 years in the sitting position. When this happens, some airways close during part of normal tidal breathing, resulting in a mismatch of ventilation and perfusion. The additive effect of these emphysema-like changes decreases arterial oxygen tension by an average rate of 0.35 mm Hg per year; however, there is a wide range of arterial oxygen tensions in elderly preoperative patients. Both anatomic and physiological dead space increase. Other pulmonary effects of aging are summarized in Table 43-2.

Decreased respiratory muscle function/mass, a less compliant chest wall, and intrinsic changes in lung function can increase the work of breathing and make it more difficult for elderly patients to muster a respiratory reserve in settings of acute illness (eg, infection). Many patients also present with obstructive or restrictive lung diseases. In patients who have no intrinsic pulmonary disease, gas exchange is unaffected by aging.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree