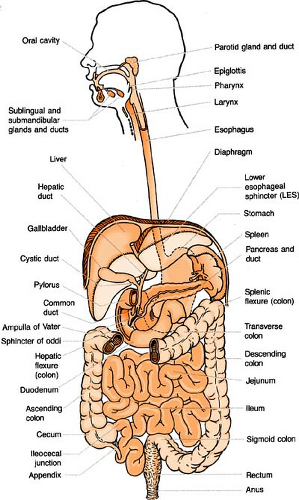

Gastrointestinal and Urinary Systems

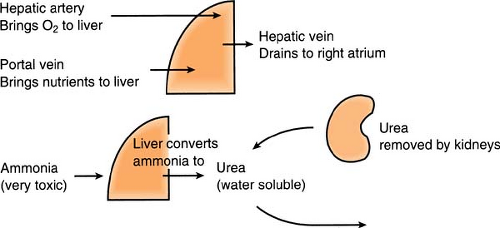

Anatomy: Liver Function

(see also Hepatic Encephalopathy, p. 232; Hepatic Failure, p. 232; Bilirubin in Part 9, p. 340)

The liver is the largest internal organ. It stores fat-soluble vitamins and conjugates bilirubin to make it water soluble for excretion by the kidneys. In hepatic failure, the liver is unable to conjugate bilirubin, leading to an increase in both direct and indirect bilirubin, as well as a buildup of ammonia.

Ascites

Ascites, an accumulation of fluid in the abdominal cavity, is caused by decreased protein content and an increase in osmolarity. It is a common complication of advanced hepatic disease. Pressure from the ascites frequently results in dyspnea. Sodium restriction is the cornerstone of therapy, along with diuretics. Paracentesis (removal of fluid from the abdominal cavity) is rarely used because it may precipitate hepatic coma, shock, or hypovolemia (see Paracentesis).

Bariatrics

Bariatrics is a collective term describing one of several surgical procedures performed on the stomach and/or intestines to help a patient with extreme obesity lose weight. It is usually reserved for those with a body mass index (BMI) of >40 (which equates to at least 100 lb over recommended weight) but also is indicated for those with a BMI of >35 who have secondary problems such as heart disease or type 2 diabetes.

To calculate body mass index:

(weight in pounds × 700) ÷ (height in inches, squared)

<18 = not enough fat 18–25 = normal >25 = too much fat

The surgeries fall into two categories for reducing caloric intake:

Restrictive only. The stomach is made smaller during surgery. The patient feels full faster and learns to decrease the amount eaten.

Malabsorptive and restrictive combined. Not only is the stomach size reduced, but part of the stomach and/or intestines are bypassed so that fewer calories are absorbed (unfortunately, nutrients are lost as well).

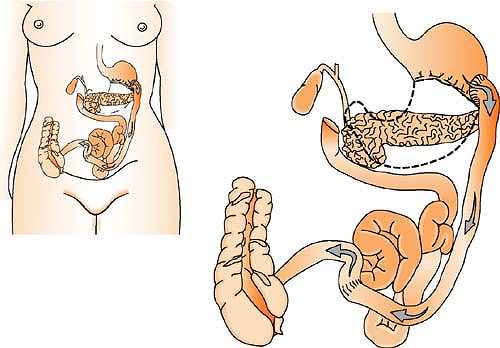

Biliopancreatic diversion (BPD) (malabsorptive and restrictive): Portions of the stomach are surgically removed, leaving only a small pouch that is connected directly to the final segment of the small intestine. The duodenum and jejunum are completely bypassed. A common channel, allowing bile and pancreatic digestive juices to mix prior to entering the colon, is left remaining. Weight loss occurs because calories go directly to the colon, where no absorption takes place.

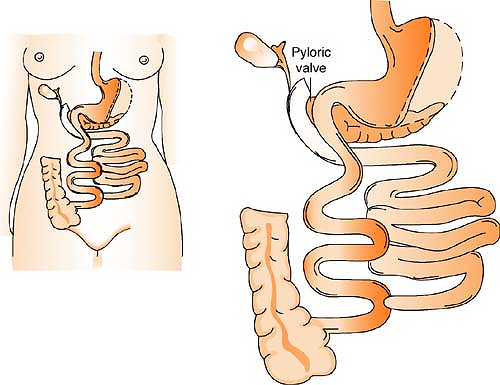

Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD/DS) (malabsorptive and restrictive): This surgery allows a larger portion of the stomach to be left intact, including the pyloric valve that regulates the release of contents from the stomach into the small intestine. The duodenum is divided near the pylorus, and the small intestine is divided as well. The portion of the small intestine connected to the large intestine is attached to the short duodenal segment next to the stomach. The remaining segment of the duodenum, connected to the pancreas and gallbladder, is attached to this limb, closer to the large intestine. Where contents from these two segments mix is called the common channel, and it dumps into the large intestine. Since this surgery fosters less nutrient absorption, a higher amount of weight loss is accomplished.

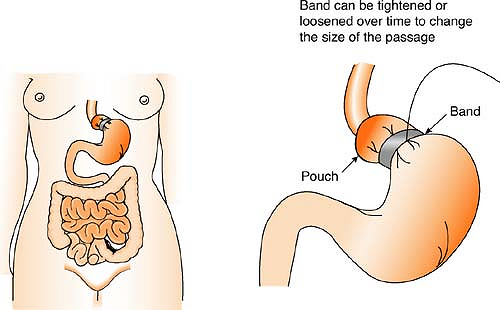

Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (restrictive only): Accomplished laparoscopically, a hollow band is placed around the stomach near its upper end, creating a small pouch and a narrow passage into the larger remaining portion of the stomach. The creation of this small passage delays the emptying of food and causes a feeling of fullness. The band can be tightened or loosened over time to change the size of the passage. Initially, the pouch holds about 1 oz. of food and later expands to hold 2 to 3 oz. This surgery has minimal metabolic effects because it does not interfere with digestion.

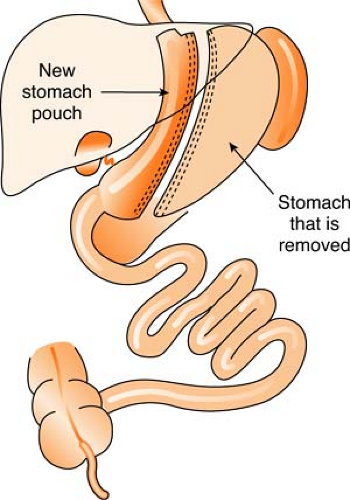

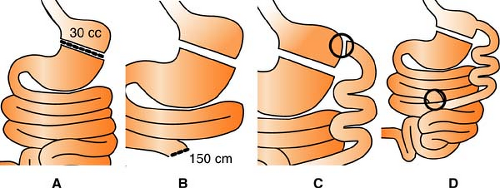

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (malabsorptive and restrictive): Performed laparoscopically since 1993, this is the most frequently performed bariatric surgery in the United States. In the following figure, the stomach is divided into two parts (A), and the small intestine is carefully measured and cut (B). The small intestine is then connected to the small pouch (C), and the bypassed part of the small intestine is reconnected, forming a “Y” (D).

Figure. Roux-en-Y Procedure. (Adapted from Bariatric Treatment Centers™ [www.bariatric.com] and Forest Health Services LLC.)

Vertical banded gastroplasty (VBG) (restrictive only): The upper stomach near the esophagus is stapled vertically to create a small pouch along the inner curve of the stomach. The outlet from the pouch to the rest of the stomach is restricted by a band. This band delays emptying of food from the pouch, creating a feeling of fullness. Because this surgery does not interfere with the normal digestive process, its success is defeated by continuance of a junk food diet.

Vertical sleeve (restrictive only): The left side of the stomach (greater curvature) is surgically removed, leaving a new stomach that resembles the size and shape of a banana.

Surgically, it is a simpler operation than laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding or biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch, since both ends of the stomach and the small intestine remain intact. The procedure is sometimes performed in one step, but more frequently, it is a two-part procedure reserved for the extremely obese or those who have so many health problems that they do not qualify for gastric bypass surgery. The first step of the procedure is to create the “sleeve,” which helps the patient begin to lose weight. After enough weight has been lost (usually 80–100 lb and sometimes requiring longer than a year), the second step can be undertaken. The “sleeve” is converted into a formal gastric bypass or duodenal switch, promoting additional weight loss and offering the patient a more permanent result.

Basal Metabolic Rate

The basal metabolic rate is a calculated value (in k/cal) that reflects the minimal caloric requirement that a resting individual needs in order to sustain life (amount of energy the body would burn if the person were sleeping for 24 hours).

General calculation: Body weight (in lb) × 10 kcal/lb

Harris Benedict equation:

Males: 66 + (13.7 × weight in kg) + (5 × height in cm) – (6.8 × age in years)

Females: 655 + (9.6 × weight in kg) + (1.7 × height in cm) – (4.7 × age in years)

Bilirubin

(see Part 9, p. 340)

Billroth Procedure

(see Ulcers, p. 242)

Bowel Management Systems

Several fecal containment systems are currently available to collect and contain liquid stool and thus preserve the integrity of the skin. They can be either external (a pouch is applied directly to skin of perianal area and attached to a gravity drainage bag) or internal (a pliable catheter is inserted into the anorectal cavity and attached to gravity drainage). Some of the newer internal systems (Zassi, ActiFlo, DigniCare, Flexi-Seal) also have irrigation and/or enema access. Containment of feces becomes increasingly important when dealing with organisms such as Clostridium difficile and vancomycin-resistant enterococci.

29 days is the general rule for maximum indwelling days.

May not be effective if distal rectum is surgically altered.

Weak sphincter tone may cause the catheter to expel or have increased leakage of stool.

Not to be used if impacted stool present.

Excessive, prolonged traction on the catheter could result in sphincter dysfunction.

Bowel Obstruction

(see also Colostomy, p. 224; Ileostomy, p. 234)

Bowel obstruction develops when intestinal contents cannot pass through the lumen of the bowel as a result of mechanical causes, neurogenic causes, or vascular abnormalities.

Types

Simple: No interference with blood supply.

Strangulated: Blood supply to obstructed segment decreases; ischemia occurs; may progress to necrosis and gangrene.

Incarcerated: Blood supply severely altered. Necrosis and gangrene occur.

Large Bowel Versus Small Bowel

| Characteristic | Large Bowel | Small Bowel |

|---|---|---|

| Stool | None | Intermittent until bowel clears, then none |

| Distension | Pronounced | Minimal |

| Vomiting | Not common | Occurs if obstruction proximal to ileum |

| Pain | Mild, steady | Cramping in upper abdominal area |

Cecostomy

(see Colostomy, p. 224)

Cirrhosis

(see also Bilirubin in Part 9, p. 340)

Cirrhosis is a disease in which liver damage is followed by scarring. Fibrous tissue forms and compresses blood, lymph, and bile channels. It is the final stage of many types of liver injury.

Portal cirrhosis (Laennec’s disease): Associated with alcoholism; the most common type. It has three components: (1) destruction of hepatic tissue, (2) diffuse increase in fibrous tissue, and (3) disorganized regeneration. The liver is enlarged and firm. An important secondary factor is the development of portal hypertension and esophageal or gastric varices (see Esophageal Varices).

Posthepatitic cirrhosis: Associated with viral or toxic hepatitis. The liver is shrunken and irregular, with large regeneration nodules and fibrous tissue.

Biliary cirrhosis: Associated with intrahepatic cholestasis. There is scarring around the ducts and lobules, and immune mechanisms may be disturbed.

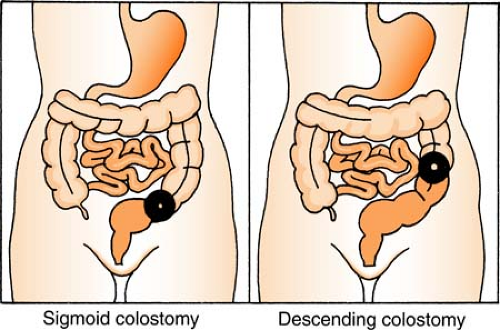

Colostomy

(see also Bowel Obstruction, p. 223, Ileostomy, p. 234)

A colostomy is the opening of some portion of colon to the abdominal surface. It is named for the section of the colon that is cut into.

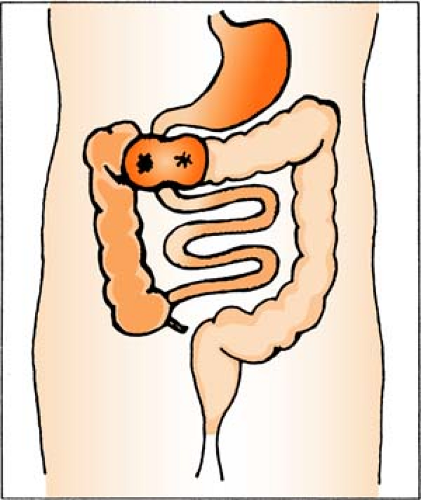

Sigmoid and Descending Colostomy

The stoma is normally in left area of colon. The rectum, anus, and damaged portion of large intestine are removed. Elimination is fecal material. Surgery is permanent; prognosis is good.

Transverse Colostomy

The stoma is usually slightly above and to one side of navel. Only the damaged portion of large intestine is removed. It usually is a “resting” process, and closure is performed later. Management can be with irrigation, which gives 50% control (stays clean 6–10 hours). Two types of colostomy are performed along the transverse colon:

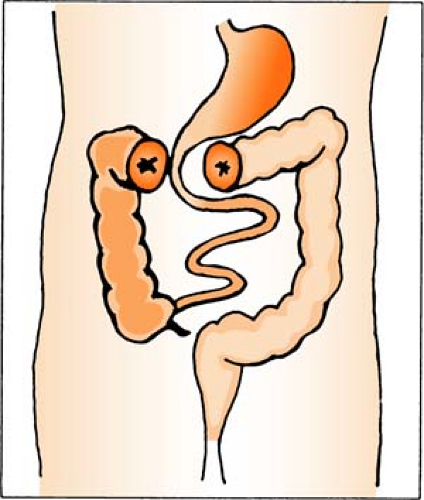

Double-Barrel Transverse Colostomy

There are two stomas: One active, one inactive. Active stoma diverts feces to outside (bypassing injury or inflammation), and inactive stoma drains mucus until healing is complete. It requires constant wearing of an appliance. The ostomy is usually closed within 6 months, and the bowel is rejoined.

Ascending Colostomy (Cecostomy)

The stoma is in right lower quadrant. It functions like an ileostomy: Elimination is thin and filled with gastric juices. Flow is constant and requires constant wearing of an appliance. Surgery is temporary.

Crohn’s Disease

(see Inflammatory Bowel Disease, p. 235)

Cullen’s Sign

(see also Pancreatitis, p. 236)

Cullen’s sign, ecchymosis around the umbilicus, is associated with severe intraperitoneal hemorrhage.

Cystostomy

(see Urinary Diversions, p. 244)

Diverticulitis

A diverticulum of the colon is an outpouching of mucosa through a weak point in the muscular layer of the bowel wall. It generally results from persistent and abnormally high intracolonic pressure. (Note: Diverticulosis is the presence of many diverticula in the sigmoid and the ascending colon. When the diverticula become inflamed, then the term “diverticulitis” is used.) The cause is unknown. At least 10% of the middle-aged population is affected. No treatment is necessary for diverticula that cause no symptoms; however, symptomatic diverticula generally require medical therapy. A possible complication is perforation with resultant abscess formation or generalized peritonitis. The inflammatory process may also cause bowel obstruction, and the patient may require surgery. Occasionally, a portion of the involved bowel is removed, and a colostomy is placed.

Duodenal Ulcer

(see Ulcers, p. 242)

Encephalopathy

(see Hepatic Encephalopathy, p. 232)

Enteral Nutrition

(see also Parenteral Nutrition, p. 238)

Enteral nutrition is an alternative method to support patients who are unable to meet their nutritional needs orally by placing a feeding tube into the gastrointestinal tract.

Nasogastric (Ng) Tube

Size: 8 to 12 French (F) when tube feeds are anticipated for <6 weeks; 14 F or larger for medications, gastric decompression, or short-term tube feeding (1–2 weeks)

Placement: Predetermined distance (usually 40–45 cm). Measure from the tip of nose to ear lobe, and from ear lobe to the tip of xiphoid process for gastric placement.

Evaluating correct placement: Radiology remains the only reliable method to verify initial placement of blindly inserted feeding tubes. The older traditional practices of verification should be discontinued because of their lack of efficacy and potential for harm:

The audible “pop” over the epigastrium with auscultation may lead to a false assumption of correct placement.

A pH of <5.0 with aspirate inspection may indicate gastric placement but is not helpful in detecting esophageal placement (aspirate could be gastric reflux).

Placing the tube in water to check for “bubbling” lacks consistency, as no bubbling may be observed with pulmonary placement if the tube ports are occluded.

Other options: More recently, the CORTRAK™ ™enteral access system has evolved, consisting of a computer monitor, receiver unit, and an electromagnetic transmitter stylet.

The system allows for a real-time representation of NG tube placement and affords the clinician the luxury of responding immediately to a misplaced tube (i.e., into a lung, or coiled in the stomach). A receiver is placed on the patient’s xiphoid process, and the NG tube is advanced. A signal is received from the stylet’s transmitter, and the real-time location of the tube is displayed. The system negates the need for multiple chest x-rays during placement, and significantly reduces the need for fluoroscopy and/or endoscopy.

Relieving tube occlusion: Feeding tubes should routinely be flushed with 30 cc of water every 4 hours and all medications followed with a 10 cc water flush (per institution policy). Nonetheless, gastric juices may still cause the proteins in the feeding solutions to reflux, and an occlusion will occur. Measures to remedy this situation include:

If there is still flow in the tube but it is sluggish, warm water should be instilled into the feeding tube and agitated with a syringe. Frequently this measure alone will clear the tube.

If there is still flow in the tube and the warm water is ineffective, a number of products have been used to dislodge the occlusion: Adolph’s Meat Tenderizer, cranberry juice, Coke, Pepsi, Sprite, and/or Mountain Dew. Although occasionally effective, the most consistent result comes with the administration of the pancreatic enzyme Viokase. When dissolved in 5 cc of water, injected, and allowed to dwell for 5 minutes, it will usually relieve the occlusion.

If the tube is completely occluded and it is impossible to instill water or enzyme, the last option is to insert a flexible wire, in an attempt to clear the tube.

Gastrostomy Tube

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy is the mainstay of long-term enteral feeding.

REMEMBER: With the G/J tube, use the “G” port for medications; use the “J” port for H2O and tube feeds ONLY.

Small Bowel Feeding Tube (Dobbhoff, Entriflex)*

To insert:

Determine the length for gastric placement (usually 50–65 cm). Measure from the tip of nose to ear lobe and from ear lobe to the tip of xiphoid process for gastric placement. Then, add approximately 10 inches (25 cm) for intestinal placement.

Secure stylet inside the feeding tube, and instill 10 to 30 cc warm water to activate the internal lubricant.

Dip the weighted tip in warm water to activate the external lubricant.

Pass through the nostril and into the patient. Once inserted, do not pull stylet back and forth to manipulate it within the tube. (This avoids damage or puncture of the lung, should the tube be in the tracheobronchial tree.)

Confirm tube placement, then remove the stylet.

Spontaneous transpyloric passage of the weighted tip to the intestine occurs within 24 to 48 hours. Placing patient in a semi-Fowler’s and positioning to the right side may expedite this process.

Enteral Nutrition Formulas

| Indication/Characteristics | Nutritional Formulas |

|---|---|

| 1 kcal/mL | Jevity, Isocal HN, Entrition HN, Osmolite, Promote |

| 1.5 kcal/mL | Ensure Plus, Jevity 1.5, Nutren 1.5, Isosource 1.5, Osmolite 1.5, Boost Plus |

| 2.0 kcal/mL | Resource 2.0, Deliver 2.0, Two Cal HN |

| 1 kcal/mL (Fiber, Low Osmo) | Jevity, Jevity 1.2, Promote with Fiber |

| Low Residue/Low Fiber | Vital High Nitrogen (Vital HN) |

| Low Residue/Isotonic | Osmolite/Osmolite 1.2 |

| Isotonic, High Protein, High Nitrogen (High proportion of calories from protein) | Promote |

| High Protein, Gluten Free, Low Residue (Wound healing) | Impact with Glutamine (1.3 kcal) |

| High Nitrogen | Two Cal HN, Isocal HN |

| Low Fat | Vivonex TEN |

| Low Carb/High Fiber—Diabetes Management | Glucerna 1.0, Glucerna 1.2, Glucerna 1.5, DiabetiSource AC |

| Renal/Dialysis (High Protein) | Nerpo—Carb Steady, Suplena—Carb Steady, Novasource Renal |

| Renal (Reduced Kidney Function) (Low Protein) | Suplena, RenalCal |

| Pulmonary—COPD/Cystic Fibrosis/Respiratory Failure | Pulmocare, Nutren Pulmonary |

| Pulmonary—SIRS/AIDS/ALI/Ventilator Dependent (Low Residue) | Oxepa |

| Pulmonary—ALI (Low CHO, High Fat, Caloric Dense ALI—1.5 cal/mL) | Nutren Pulmonary |

| High Calorie/Low Residue/Gluten and Lactose Free | Hi-Cal |

| High Fiber/High Protein | Fibersource HN/Promote with Fiber |

| Fiber | Promote with Fiber, Jevity 1.0, Jevity 1.2, Jevity 1.5, Benefiber Powder |

| Modular Components | Glutasolve (90 kcal/pkg with 15 g L-glutamine) Juven (78 kcal/pkg with 14 g protein) MCT oil (115 kcal/Tbsp (15 mL) with 14 g fat) Protein Powder (25 kcal/mL) |

| Elemental Formulas (High-nitrogen, low-fat elemental formulas for malabsorptive disease states) | Crucial, Vivonex Plus, Vivonex RTF, Vivonex TEN, Peptamen, Tolerex |

| Semielemental Formulas (Immune Enhancing) | Perative (1.3 kcal) |

| Burns/Malabsorptive/Pancreatitis | Optimental |

| High Protein/Immune Support | Pivot 1.5, Perative |

| Hepatic Support | Nutrihep, Osmolite, Jevity 1.0, Suplena |

| Wound Healing | Crucial, Arginaid, Impact, Juven |

| General Supplement | Ensure Plus, Ensure, Boost, Boost Plus |

| Abbott-Nutrition and Nestle’-Nutrition are currently the main suppliers of the tube feeding products. Additional research may be obtained online to select the product that best meets the patients’ nutritional requirements. | |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree