Gastroenterologic Cancers

ESOPHAGEAL CANCER

Richard W. Golub MD, FACS

Nuria Lawson MD

Cancer of the esophagus is a rare but aggressive malignancy, the etiology of which remains uncertain. Most patients present with locally advanced disease and have a poor overall survival rate and diminished quality of life. Approximately 95% of patients who have esophageal cancer will die from it, and 75% of patients will die within 1 year of diagnosis. Efforts to lower mortality rates in the United States have so far been disappointing. Despite many new and innovative approaches to the treatment of esophageal cancer, the 5-year survival rate has shown only modest improvement. Screening the population at large for early and perhaps treatable esophageal cancer is difficult and impractical. Nevertheless, epidemiologic data suggest that the incidence of esophageal cancer can be greatly reduced if environmental risk factors are controlled. In addition, identifying patients at risk for this disease increases the likelihood that patients will present with earlier, more favorably staged disease.

ANATOMY, PHYSIOLOGY, AND PATHOLOGY

The esophagus is a muscular tube, approximately 18 to 26 cm long, that extends from the level of the 6th cervical to the 11th thoracic vertebra. It has no significant secretory or absorptive functions and works solely to transport swallowed material from the pharynx to the stomach. In its mediastinal course, the esophagus is closely related to the trachea, bronchus, pulmonary veins, pericardium, and left atrium anteriorly, the pleura and lungs laterally, and the vertebral column and thoracic aorta posteriorly. Separating the esophagus from the vertebral column are the thoracic duct, azygos and hemiazygos veins, and posterior intercostal arteries. Unlike the remainder of the gastrointestinal tract, the esophagus has no serosa. It is separated from adjacent structures by only a loose connective tissue that provides little barrier to the local spread of tumor.

For convenience, the esophagus is often divided into upper, middle, and lower thirds. The upper third extends to the aortic arch, the middle third to the inferior pulmonary vein, and the lower third to the esophagogastric junction.

Cancer of the esophagus has a propensity for rapid invasion of the esophageal wall and easy, widespread dissemination by way of a rich lymphatic supply. In general, lymphatic metastases involve the regional nodes closest to the site of primary tumor. However, because of the rich anastomoses of intramural lymphatic channels, nodal involvement may occur at substantial distances from the primary lesion.

Distant metastases can be found anywhere throughout the body. The liver, lungs, pleura, and kidneys are the most common sites, but the adrenal glands, bone, brain, heart, and peritoneum can be involved. Occasionally, the tumor may extend directly into mediastinal structures before distant metastasis is evident.

PATHOLOGY

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common tumor of the esophagus, accounting for approximately 95% of esophageal cancers worldwide and 60% of esophageal cancers in the United States. Unless detected in its earliest stages, it is usually fatal in less than 5 years. Histologically, the tumor is composed of sheets of polygonal or polyhedral cells with varying degrees of differentiation. Well-differentiated tumors contain features such as keratin pearls and intercellular bridges, whereas poorly differentiated tumors have marked nuclear and cellular pleomorphism. The majority of tumors, however, are moderately differentiated. Macroscopically, 60% of these lesions are fungating intraluminal growths, 25% are ulcerative lesions associated with extensive infiltration of the adjacent esophageal wall, and 15% are infiltrating. Approximately 8% of tumors occur in the cervical esophagus, 55% in the upper and midthoracic segments, and 37% in the lower thoracic segment (Orringer, 1997).

Adenocarcinoma

Adenocarcinomas can arise at any level but are located most often at or near the gastroesophageal junction. Histologically, various degrees of glandular differentiation are noted, but well-differentiated tumors predominate. Esophageal adenocarcinoma is typically flat or ulcerated, although about one third of lesions are polypoid or fungating.

Other Malignancies

Several other rare types of esophageal malignant tumors occur, and all have a poor prognosis. Anaplastic small cell (oat cell) carcinoma accounts for fewer than 2% of esophageal cancers. Like their pulmonary counterparts, they arise from the APUD cell system and demonstrate neurosecretory granules on electron microscopy. Malignant melanoma is exceedingly rare and constitutes less than 0.1% of esophageal malignancies. The tumor is more common in men and is clinically indistinguishable from other esophageal neoplasms. Adenoid cystic carcinoma typically occurs as a middle-third esophageal tumor and is usually discovered late in its course. Carcinosarcoma of the esophagus (also known as pseudosarcoma, spindle cell carcinoma, or polypoid carcinoma) is a tumor with histologic features of both squamous cell carcinoma and malignant spindle

cell sarcoma. Found primarily in the distal two thirds of the esophagus, it can grow large (10 to 15 cm) (Xu et al, 1984, Orringer, 1997). Sarcomas of the esophagus are rare, but a number of variants have been described. These include leiomyosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, liposarcoma, and malignant mesenchymoma. Primary malignant lymphoma is also infrequent but is occasionally reported in patients with AIDS (Moses et al, 1995). Finally, involvement of the esophagus by another primary tumor, either by direct extension or metastatic spread, has been reported with cancers of the breast, lung, liver, kidney, prostate, and stomach (Kadakia et al, 1992; Vansant & Davis, 1971; Nussbaum & Grossman, 1976).

cell sarcoma. Found primarily in the distal two thirds of the esophagus, it can grow large (10 to 15 cm) (Xu et al, 1984, Orringer, 1997). Sarcomas of the esophagus are rare, but a number of variants have been described. These include leiomyosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, liposarcoma, and malignant mesenchymoma. Primary malignant lymphoma is also infrequent but is occasionally reported in patients with AIDS (Moses et al, 1995). Finally, involvement of the esophagus by another primary tumor, either by direct extension or metastatic spread, has been reported with cancers of the breast, lung, liver, kidney, prostate, and stomach (Kadakia et al, 1992; Vansant & Davis, 1971; Nussbaum & Grossman, 1976).

EPIDEMIOLOGY

There is wide variation in the incidence of esophageal carcinoma throughout the world. Although the disease is uncommon in most of Western Europe and the United States, clusters of high incidence occur in certain parts of Asia and Africa. Esophageal cancer is of epidemic proportion in northeastern Iran, the Transkei of South Africa, Linxian County in the Henan province in northern China, certain areas of southern Russia, India, the Middle East, Singapore, southern Uruguay, and sporadic areas in Europe such as northern France and Italy (Duranceau, 1988). According to the World Health Organization, mortality rates are highest in China, Puerto Rico, and Singapore (Roth et al, 1997). This variation, which cannot be explained by differences in reporting, indicates a great geographic range in etiologic factors for this cancer.

By comparison, esophageal cancer is relatively uncommon in North America, Australia, and most European countries, where the reported incidence is 3 to 10 cases per 100,000 population. The peak incidence is between the fifth and seventh decades, and men predominate by six- to eightfold. The incidence among African American men (16.8/100,000) is higher than that of any other ethnic group. For both African American men and women, the death rate is approximately three times the rate in the white population (Duranceau, 1988).

Since the mid-1970s, tumor registry data obtained from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program have shown a decrease in the incidence of squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus and an increase in adenocarcinoma of 5% to 10% per year (Blot et al, 1991). This increase exceeded that of any other cancer during this period. In fact, nearly half of all newly diagnosed cases of esophageal cancer in the United States are adenocarcinomas, and white men account for the majority of these cases (Blot et al, 1991; Blot et al, 1993; Daly et al, 1996). Most of these tumors arise in the lower third of the esophagus in the sixth decade of life and have a male/female ratio of 3:1.

ETIOLOGY AND RISK FACTORS

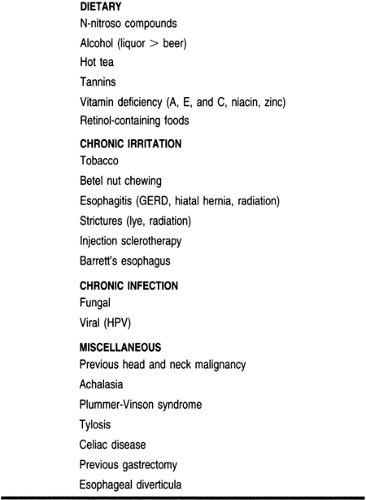

The etiology of esophageal carcinoma remains unknown, but a number of factors, such as environmental exposure, dietary habits, chronic mucosal irritation, infection, cultural influences, and genetic predisposition, have been implicated (Table 24-1). A complex interaction among these risk factors probably exists, and their effects may be additive or even synergistic.

Several epidemiologic studies implicate tobacco use and alcohol consumption as predisposing factors in the development of squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus, especially in the United States and Western Europe (Schoenberg et al, 1971; Pottern et al, 1981). The risk from alcohol is directly related to the quantity and the type of alcohol ingested, hard liquor posing a greater threat than wine or beer (Pottern et al, 1981).

Although cigarettes have received the most attention, tobacco can be carcinogenic in any form. Pipe tobacco, cigars, snuff, and chewing tobacco all increase the risk (Rogot & Murray, 1980; Doll & Peto, 1976; Mimic et al, 1988; Altorki et al, 1992). The precise mechanism of tobacco carcinogenesis has not been fully characterized, but smoke constituents such as nitrosamines presumably play a role. In general, smokers run a risk four times greater than nonsmokers of developing esophageal cancer (Krevsky, 1995).

Multiple risk factors for the development of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus have been proposed. Unlike squamous cell carcinoma, there is no evidence that tobacco, alcohol, or diet plays a major pathogenic role in the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma. The only known predisposing factor is Barrett’s mucosa (metaplastic columnar epithelium), with severe dysplasia developing from chronic gastroesophageal reflux. Patients with a columnar-lined lower esophagus (Barrett’s metaplasia) are 40 times more likely to develop adenocarcinoma than the general population (Cameron et al, 1985; Orringer, 1997).

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

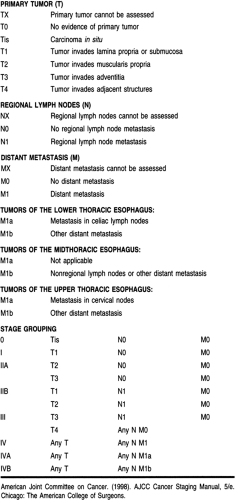

After a histologic diagnosis is made, patients with esophageal carcinoma are best staged by the Tumor–Node–Metastasis (TNM) system developed jointly by the American Joint Committee on Cancer and the International Union Against Cancer. In this system the esophagus is divided into four regions:

Cervical, from the lower border of the cricoid cartilage to the thoracic inlet, approximately 18 cm from the upper incisor teeth

Upper thoracic, from the thoracic inlet to the tracheal bifurcation at approximately 24 cm

Midthoracic, from the tracheal bifurcation to half the distance to the esophagogastric junction at 32 cm

Lower thoracic, extending to 40 cm and including the intra-abdominal portion of the esophagus and the esophagogastric junction (AJCC, 1997).

The most recent TNM classification and stage grouping is presented in Table 24-2.

In addition to stage, several aspects of tumor biology are associated with a poor prognosis. These include a poor histopathologic grade, DNA ploidy status, and a high score on the argyrophilic nucleolar organizer regions test (AgNOR number) (Haskell, 1995). Anatomic location has also been found to have prognostic significance, with upper and midthoracic lesions having a less favorable outcome than other sites (AJCC, 1997).

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

History

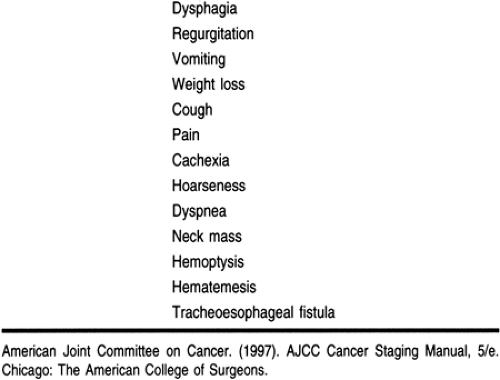

Dysphagia and weight loss are the initial symptoms of carcinoma of the esophagus in 90% of patients (Table 24-3). Unfortunately, these are late symptoms in the natural history of the disease. Because of its distensibility, difficulty in swallowing does not occur until at least half the circumference of the esophagus has been infiltrated by cancer (Skinner, 1976). By this time, the tumor may have grown to a significant size, with local invasion or metastases. Occasionally, the onset of dysphagia is sudden, but most patients complain of an ill-defined retrosternal discomfort or a vague difficulty in swallowing for the preceding 3 to 6 months. Although most patients can localize the site of obstruction, this does not always correlate with the actual location of the tumor. Odynophagia (painful swallowing) occurs in more than 20% of patients and may be the only presenting symptom. Weight loss is common, but severe weight loss and cachexia are infrequently seen and are usually indicative of locally advanced or widespread disease. Patients may also experience regurgitation of undigested food, epigastric pain, or aspiration pneumonia.

Advanced lesions may present with a variety of symptoms such as hematemesis, melena, superior vena cava syndrome, cough from a bronchoesophageal or tracheoesophageal fistula, hemoptysis, or problems related to nerve involvement (ie, Horner’s syndrome or paralysis of the recurrent laryngeal or phrenic nerve) (Akiyama, 1990; Roth et al, 1997). Aortoesophageal fistula is a rare but lethal complication. Other signs of unresectable malignant disease may be found with malignant pleural effusion or malignant ascites.

Physical Examination

Apart from features of recent weight loss, the physical examination is often unremarkable, and the diagnosis of esophageal cancer will depend on radiographic or endoscopic data. However, the physical examination should encompass a thorough search for evidence of metastases. Supraclavicular or cervical lymph nodes should be sought and samples taken for biopsy if palpable. Enlargement of the left gastric, celiac, and retropancreatic nodes may be palpable in thin or cachectic patients, and there may be hepatomegaly in patients with liver metastases. Other evidence of intra-abdominal disease includes the presence of an epigastric mass, ascites, enlarged ovaries (Krukenberg tumors), or a Blumer’s shelf on rectal examination (Fok & Wong, 1996). Documentation of metastatic disease establishes the presence of a stage IV tumor.

Disease Course

Squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus is an aggressive tumor. It tends to infiltrate locally, involving adjacent lymph nodes and metastasizing widely by lymphatic or hematogenous routes. Lack of an esophageal serosal layer tends to favor local tumor extension into such structures as the pericardium, aorta, tracheobronchial tree, diaphragm, and left recurrent laryngeal nerve. Lymph node metastases are present in at least 75% of patients at the time of diagnosis. Distant spread to the liver and lung is common. The overall prognosis of invasive squamous cell carcinoma is poor, with only 5% to 12% of patients surviving 5 years. Extraesophageal tumor extension is present in 70% of cases at the time of diagnosis, and the 5-year survival rate is only 3% when lymph node metastases are present, compared with 42% when there is no lymph node spread (Orringer, 1997).

As is the case with squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma of the esophagus exhibits aggressive behavior, with frequent transmural invasion and lymph node metastases. Distant spread is common, with the liver and lung most frequently involved. The 5-year survival rate for esophageal adenocarcinoma is only 0% to 7%, with the presence of lymph node metastases significantly decreasing survival (Orringer, 1997).

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Laboratory abnormalities are often nonspecific in patients with esophageal cancer, but they may reflect the disease stage and assist clinicians in deciding on appropriate therapy. Bleeding may result in microcytic anemia. Malnutrition may reduce the serum albumin and cholesterol levels and the white blood cell count. Elevated liver enzyme levels may be an indication of hepatic metastases. Hypercalcemia, which has been associated with a poor prognosis, has been reported in 16% to 28% of patients (Kuwano et al, 1989; Axelrad & Fleischer, 1998). The role of serum tumor markers, such as carcinoembryonic antigen, CA 19-9, CA-50, and T-4, is uncertain. Although their levels are elevated in many patients, there is still no good evidence for their use in diagnosis or screening for esophageal cancer. Pulmonary function testing and arterial blood gas measurements are helpful to quantify the extent of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Patients with underlying coronary artery disease should have an echocardiogram to assess left ventricular function and a stress test to assess the extent of ischemic heart disease.

A plain chest x-ray provides limited information in patients with esophageal cancer. Possible abnormalities include an air–fluid level secondary to an obstructed esophagus, infiltrates suggesting aspiration pneumonia, tracheal deviation, pulmonary nodules, pleural effusion, and mediastinal widening from lymphadenopathy. The chest film, however, may be deceptively normal, even with advanced disease.

Because dysphagia is the presenting complaint in 80% to 90% of patients with esophageal carcinoma, any patient who complains of progressive dysphagia warrants both a barium esophagogram and esophagoscopy to rule out carcinoma. Barium swallow is usually the first procedure that identifies the lesion and should precede esophagoscopy whenever possible. The location of the tumor, its length, its gross pathologic characteristics, and its relation to adjacent structures may all be assessed by this study. The typical esophageal carcinoma presents with an irregular, ragged mucosal pattern with luminal narrowing. Irregular filling defects may represent polypoid or fungating lesions, and advanced tumors may present with complete luminal occlusion or demonstration of a tracheoesophageal fistula.

Regardless of how suspicious a lesion appears on contrast swallow, esophagoscopy with biopsy is mandatory to establish the diagnosis. This is especially true if cancer is suspected and the barium esophagogram is normal. Flexible fiberoptic or video endoscopy permits the direct visualization of the esophageal tumor, its anatomic extent, and associated or secondary lesions.

Accurate tissue specimens can be obtained easily under direct visual control using endoscopic instruments. Multiple biopsy specimens provide a positive yield of 85%, and in combination with brush cytology, accuracies of 90% to 100% should be readily attainable (Winawer et al, 1976).

Upper endoscopy should also include direct visualization of the oropharynx, hypopharynx, epiglottis, vocal cords, and the stomach and duodenum. The ability to inspect these regions permits the detection of synchronous lesions and allows assessment of the suitability of the stomach and duodenum for esophageal replacement.

Clinical Staging

Once the diagnosis of esophageal carcinoma has been established histologically, staging of the tumor is the next critical step in determining which therapeutic option is appropriate.

Computed tomography (CT) of the chest and upper abdomen is now the standard noninvasive technique for staging esophageal carcinoma. It may be of value in determining surgical

resectability or planning for radiation therapy or endoscopic palliation. CT scanning permits evaluation of esophageal wall thickness, mediastinal invasion, and the presence of regional or distant metastases. It is particularly useful in assessing local extension of disease and its relation to adjacent structures, especially when oral contrast medium is used. It is less accurate in assessing the degree of periesophageal lymph node involvement and often underestimates the length of the esophageal lesion.

resectability or planning for radiation therapy or endoscopic palliation. CT scanning permits evaluation of esophageal wall thickness, mediastinal invasion, and the presence of regional or distant metastases. It is particularly useful in assessing local extension of disease and its relation to adjacent structures, especially when oral contrast medium is used. It is less accurate in assessing the degree of periesophageal lymph node involvement and often underestimates the length of the esophageal lesion.

Experience with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) seems to indicate that it does not have any particular advantage over CT and shares many of its limitations. A major problem with MRI is lack of a suitable intraluminal contrast agent. A direct comparison of CT and MRI found a comparable accuracy in predicting resectability, with both sensitivity and specificity of 85% (Takashima et al, 1991; Krevsky, 1995).

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) can define the depth of tumor wall invasion and associated paraesophageal lymph nodes. The use of EUS may be limited if there is an obstructing tumor that cannot be traversed by the ultrasound probe. In patients in whom the probe can be positioned within the esophageal lumen involved by tumor, however, this procedure has an 86% accuracy in defining involved mediastinal lymph nodes (Orringer, 1997).

Depending on the location of the tumor, some patients may require additional staging modalities such as mediastinoscopy, bronchoscopy, laparoscopy, thoracotomy, or thoracoscopy. Bronchoscopy may be useful in patients with carcinomas of the upper and middle third of the esophagus to evaluate for airway invasion. Endoscopic evidence of invasion to the tracheobronchial tree precludes a safe esophagectomy. Similarly, laparoscopic and thoracoscopic staging of esophageal cancer has been found to be advantageous. Preliminary results indicate that with its use, correct staging of esophageal tumors approaches 90%.

TREATMENT OPTIONS, EXPECTED OUTCOMES, AND COMPREHENSIVE MANAGEMENT

Operative Management

Surgical resection is the primary treatment modality for patients with carcinoma of the esophagus in the absence of known metastatic disease or medical contraindications to surgery. It is the only proven curative single-treatment modality for esophageal cancer and remains the gold standard by which all other therapeutic modalities are measured. Unfortunately, only half of patients have resectable disease at the time of presentation. The goal of surgical resection is the eradication of all disease, including regional lymph nodes, while relieving dysphagia and maintaining gastrointestinal continuity. Esophageal resection with lymphadenectomy offers the best chance for long-term survival in these patients, with many achieving 20% 5-year survival rates (Lee & Miller, 1997).

There are a variety of operative procedures used for the resection of esophageal cancers and subsequent reconstruction of the alimentary tract. The choice of procedure depends on many factors, including the preference of the surgeon, the location of the tumor, the patient’s age and physiologic fitness, and the extent of disease on EUS and intraoperative staging. Of these, location of the tumor and the surgeon’s preference are probably the two most important.

The most radical procedure is the en bloc resection. If preoperative staging is favorable, this procedure is undertaken with curative intent. The objective of en bloc resection is complete removal of the tumor with wide margins, together with most of the esophagus, adjacent connective tissue, and lymph nodes. Reconstruction of the gastrointestinal tract is usually accomplished with a gastric pull-up, but small bowel or colon can be substituted if necessary.

Regardless of the procedure used, surgical resection can be a formidable undertaking. Morbidity and mortality rates can be significant and are mainly caused by cardiopulmonary complications. A well-rehearsed team of experienced surgeons, anesthesiologists, intensivists, and support staff is critical for a successful outcome.

Radiation Therapy

Although squamous cell carcinoma is generally believed to be radiosensitive, radiation therapy as a single modality of treatment seldom achieves cure in patients with carcinoma of the esophagus. The 5-year survival rate is only 6% (Earlam & Cunha-Melo, 1980). Locoregional failure has been the main limitation and can be expected in 60% to 80% of patients (Axelrad & Fleischer, 1998). Despite these results, radiation is an important method of nonoperative palliation and provides relief of dysphagia in approximately 80% of patients, one half of whom will remain free of dysphagia until the time of death (DeMeester, 1997).

Endoluminal radiation therapy (brachytherapy) works by implanting a radioactive source directly at the tumor bed. Delivery of radiation by this means theoretically provides maximal effect to the tumor itself, with minimal risk to surrounding tissues. A complete or partial response has been seen in more than 90% of patients, and more than 90% experience significant relief of dysphagia (DeMeester, 1997). Unfortunately, nearly half of patients experience moderate to severe complications that require further therapy. Additional evaluation is therefore required to determine the ultimate role of this modality in the treatment of esophageal cancer.

Chemotherapy

Unlike surgery and radiation therapy, systemic chemotherapy has a theoretical advantage in treating esophageal cancer because most patients present with widespread systemic disease. Several drugs have been used against esophageal carcinoma, but when administered as single agents the responses are usually partial and short-lived. This has prompted an evaluation of combination chemotherapy; most protocols include cisplatin in combination with 5-fluorouracil, bleomycin, methotrexate, and vindesine. Unfortunately, with the exception of the potential to improve resectability, none of these regimens has proven effective in providing local control or improving survival.

Multimodal Therapy

Since the late 1970s, esophageal cancer trials have focused on adding chemotherapy to radiation therapy or surgical resection. The rationale is to control distant disease while dealing directly with the locoregional tumor. There is also the suggestion that certain chemotherapeutic agents may act as radiation sensitizers,

thereby enhancing the efficacy of radiation therapy. At present, several ongoing studies are evaluating this form of therapy. Although surgical resectability has been improved, a clear survival advantage has not been seen. Most authors also report significant morbidity and mortality rates. Hence, there is no role for this form of therapy outside of a formal protocol.

thereby enhancing the efficacy of radiation therapy. At present, several ongoing studies are evaluating this form of therapy. Although surgical resectability has been improved, a clear survival advantage has not been seen. Most authors also report significant morbidity and mortality rates. Hence, there is no role for this form of therapy outside of a formal protocol.

Nonoperative Options

Because most patients with esophageal cancer present with advanced disease, curative treatment is generally not possible and palliation is the primary goal. Palliative options include surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, endoscopic therapy, or supportive management only.

Mechanical dilatation is a simple and inexpensive modality that can afford relief of dysphagia in up to 70% of patients. Maloney (mercury-filled rubber) bougies or Eder-Puestow (metal olives) or Savary-Gilliard (tapered plastic) dilators have all been used successfully. Unfortunately, the procedure has a 15% failure rate and relief of dysphagia is short-lived. Complications, such as perforation and bleeding, occur in 2% to 10% of patients (DeMeester, 1997). Dilatation is useful, however, as the initial step in several alternative nonoperative palliative techniques.

Transoral intubation with a prosthesis is the most popular worldwide method for palliating advanced esophageal cancer. Advantages include simplicity, short hospitalization, and immediate improvement in dysphagia. The overall reported mortality rate ranges from 3% to 15%, and a 20% to 60% complication rate has been reported (DeMeester, 1997; Orringer, 1997). Although most patients have improved swallowing, only 10% to 50% can eat solid food. The average length of survival after palliative intubation for esophageal carcinoma is less than 6 months (Orringer, 1997). Recently, self-expanding metallic stents have been introduced in an effort to improve the ease of insertion and to lessen the complications of the standard prosthesis.

Endoscopic laser therapy is most commonly performed with a Nd-Yag (neodymium-yttrium-aluminum-garnet) laser because of its deep tissue penetration and reliable hemostatic property. Relief of dysphagia occurs in 70% to 85% of patients, but multiple treatments are usually required. The dysphagia-free period is only 6 to 8 weeks.

Photodynamic therapy has recently emerged as a more selective form of laser treatment. This involves injecting a hematoporphyrin derivative, which is selectively retained by neoplastic and reticuloendothelial tissues. Argon dye lasers or gold vapor lasers are typically used to activate the hematoporphyrin derivative, leading to release of free oxygen radicals and cell death. Limited experience with photodynamic therapy is available for esophageal cancer. Although potentially curative for early tumors, possible complications, such as stricture, hemorrhage, and perforation, have not been adequately assessed (Krevsky, 1995; Likier et al, 1991).

Injection therapy has been performed with a variety of agents, such as absolute alcohol and sodium morrhuate (Payne-James et al, 1990). The technique involves passing an endoscope beyond the tumor and injecting 0.5- or 1-mL aliquots of sclerosant directly into the tumor. Tumor necrosis and restoration of luminal patency have been achieved. The experience, however, has not been extensive, and long-term results are inconclusive.

REFERRAL POINTS AND CLINICAL WARNINGS

Multiple treatment options and combinations have been used in the treatment of esophageal carcinoma. Because there is no standard regimen, joint assessment and management planning by a team including the primary care provider, gastroenterologist, surgeon, oncologist, and radiation therapist is often valuable. Generally, the goal of palliation is relief of dysphagia and prolongation of life, but it may also include pain management, nutritional support, or attention to the psychosocial and spiritual well-being of the patient and family.

CLINICAL PEARLS

Most patients with esophageal carcinoma have widespread disease at the time of diagnosis.

The physical examination should focus on identifying metastatic disease and comorbid factors.

Cure is rarely achieved.

The goals of palliation are relief of dysphagia and prolongation of life.

The risk of developing esophageal cancer can be reduced by dietary and lifestyle modification.

References

Akiyama, H. (1990). Surgery for cancer of the esophagus. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 10.

Altorki, N.K., Lightdale, C.J., & Skinner, D.B. (1992). Tumors of the esophagus. In S.J. Winawer (Ed.). Management of gastrointestinal disease. New York: Gower Medical Publishing; 1992, 24.1–24.31.

American Joint Committee on Cancer. (1997). Esophagus. In I.D. Fleming, J.S. Cooper, D.E. Henson, et al. (Eds.). AJCC cancer staging manual, 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1997, 65–69.

Axelrad, A.M., & Fleischer, D.E. (1998). Esophageal tumors. In M. Feldman, B.F. Scharschmidt, M.H. Sleisenger (Eds.). Sleisenger & Fordtran’s gastrointestinal and liver disease, 6th ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 540–554.

Blot, W.J., Devesa, S.S., & Fraumeni, J.F., Jr. (1993). Continuing climb in rates of esophageal adenocarcinoma: An update. JAMA, 270, 1320.

Blot, W.J., Devesa, S.S., Kneller, R.W., et al. (1991). Rising incidence of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastric cardia. JAMA, 265, 1287–1289.

Cameron, A.J., Ott, B.J., & Payne, W.S. (1985). The incidence of adenocarcinoma in columnar-lined (Barrett’s) esophagus. N Engl J Med, 313, 857.

Daly, J.M., Karnell, L.H., & Menck, H.R. (1996). National cancer data base report on esophageal carcinoma. Cancer, 78, 1820–1828.

DeMeester, T.R. (1997). Esophageal carcinoma: Current controversies. Seminars in Surgical Oncology, 13, 217–233.

Doll, R., & Peto, R. (1976). Mortality in relation to smoking: 20 years’ observation on male British doctors. British Medical Journal, 2, 1525–1536.

Duranceau, A. (1988). Epidemiologic trends and etiologic factors of esophageal carcinoma. In N.C. Delarue, E.W. Wilkins Jr., J. Wong (Eds.). International trends in general thoracic surgery, vol. 4: Esophageal cancer. St. Louis: C.V. Mosby; 3–10.

Earlam, R., & Cunha-Melo, J.R. (1980). Oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma: II. A critical review of radiotherapy. British Journal of Surgery, 67, 457–461.

Fok, M., & Wong, J. (1996). Oesophagus. In T.G. Allen-Mersh (Ed.). Surgical oncology. London: Chapman & Hall; 127–138.

Haskell, C.M., Lavey, R.S., Ramming, K.P. (1995). Esophagus. In Haskell (ed.) Cancer treatment, 4th ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 439–451.

Kadakia, S.C., Parker, A., & Canales, L. (1992). Metastatic tumors to the upper gastrointestinal tract: Endoscopic experience. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 87, 1418.

Krevsky, B. (1995). Tumors of the esophagus. In W.S. Haubrich, F. Schaffner, J.E. Berk (Eds.). Bockus Gastroenterology, 5th ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 534–557.

Kuwano, H., Baba, H., Matsuda, H., et al. (1989). Hypercalcemia related to the poor prognosis of patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Journal of Surgical Oncology, 42, 229.

Lee, R.B., & Miller J.I. (1997). Esophagectomy for cancer. Surgical Clinics of North America, 77, 1169–1196.

Likier, H.M., Levine, J.G., & Lightdale, C.J. (1991). Photodynamic therapy for completely obstructing esophageal carcinoma. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, 37, 75–78.

Mimic, Y., Garabrant, D.H., Peters, J.M., et al. (1988). Tobacco, alcohol, diet, occupation and cancer of the esophagus. Cancer Research, 48, 3843–3848.

Moses, A.E., Rahav, G., Bloom, A.I., et al. (1995). Primary lymphoma of the esophagus in a patient with AIDS. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, 21, 327.

Nussbaum, M., & Grossman, M. (1976). Metastases to the esophagus causing gastrointestinal bleeding. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 66, 467–472.

Orringer, M.B. (1997). Tumors, injuries, and miscellaneous conditions of the esophagus. In L.J. Greenfield, M.W. Mulholland, K.T. Oldham et al (Eds.). Surgery: Scientific principles and practice, 2d ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 694–735.

Payne-James, J.J., Spiller, R.C., Misiewicz, J.J., & Silk, D.B.A. (1990). Use of ethanol-induced tumor necrosis to palliate dysphagia in patients with esophagogastric cancer. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, 36, 42–43.

Pottern, L.M., Morris, L.E., Blot, W.J., et al. (1981). Esophageal cancer among black men in Washington DC: I. Alcohol, tobacco, and other risk factors. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 67, 777–783.

Rogot, E., & Murray, J.L. (1980). Smoking and causes of death among U.S. veterans: 16 years of observation. Public Health Reports, 95, 213–222.

Roth, J.A., Putnam, J.B., Jr., Rich, T.A., & Forastiere, A.A. (1997). Cancer of the esophagus. In J.T. DeVita, Jr., S. Hellman, S.A. Rosenberg (Eds.). Cancer: Principles & practice of oncology, 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 980–1021.

Schoenberg, B.S., Bailar, J.C., & Fraumeni, J.R. (1971). Certain mortality patterns of esophageal cancer in the United States. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 46, 1930.

Skinner, D.B. (1976). Esophageal malignancies: Experience with 110 cases. Surgical Clinics of North America, 56, 137–147.

Takashima, S., Takeuchi, N., Shiozaki, H., et al. (1991). Carcinoma of the esophagus: CT vs. MR imaging in determining resectability. American Journal of Roentgenology, 156, 297–302.

Vansant, J.H., & Davis, R.K. (1971). Esophageal obstruction secondary to mediastinal metastases from breast carcinoma. Chest, 60, 93–95.

Winawer, S.J., Melamed, M., & Sherlock, P. (1976). Potential of endoscopy, biopsy, and cytology in the diagnosis and management of patients with cancer. Clinical Gastroenterology, 5, 575–595.

Xu, L., Sun, C., Wu, L., et al. (1984). Clinical and pathological characteristics of carcinosarcoma of the esophagus: Report of four cases. Annals of Thoracic Surgery, 37, 197.

GASTRIC CANCER

Francis Cannizzo Jr. MD, PhD

Richard W. Golub MD, FACS

Cancer of the stomach is a disease with an almost uniformly poor prognosis. This, combined with its global distribution, makes gastric cancer a major worldwide public health concern. Research into the basic biology, prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of this disease has accrued over the past century. In that time, though, the greatest reduction in overall morbidity and mortality rates has been realized through primary prevention via public health initiatives and tertiary treatment by the introduction and refinement of new surgical techniques.

ANATOMY, PHYSIOLOGY, AND PATHOLOGY

Gastric Carcinoma

The vast majority of gastric malignancies are carcinomas. The incidence of gastric carcinoma increases with age. The current view is that carcinomas of the stomach have a long latency period that is often associated with recognizable precancerous lesions. Gastric acid inhibits the growth of bacteria within the stomach. Bacteria have been demonstrated to generate carcinogenic nitrosamine compounds from salivary and dietary nitrates. Conditions that lead to gastric achlorhydria may therefore predispose to gastric cancer. Intestinal metaplasia and chronic atrophic gastritis are two conditions associated with achlorhydria that have been linked with gastric cancer in correlation studies. Both chronic atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia are more prevalent in areas with high rates of gastric cancer (Dobrilla et al, 1994).

Helicobacter pylori is a recently discovered microaerophilic, gram-negative, spiral-shaped bacterium that commonly has been found in patients with acute and chronic inflammation of the gastric antrum. Because of the known association between gastritis and gastric cancer, there has been speculation about the role of H. pylori in the causation of gastric cancer, and several large cohort studies have confirmed this suspicion. However, H. pylori infection is common in the general population, and most persons with H. pylori will not develop cancer (Mera, 1995; Graham et al, 1995).

One reason for the lack of success in indicting a particular agent or sequence as the definitive cause of gastric carcinoma is the large number of strongly associated factors that have been studied. The sharp fall in gastric cancer in this country began in 1930, shortly after the passage and enforcement of the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1927. This realization contributed to a search for a nutritional cause of gastric cancer that began in the 1950s and continues today. In the course of that work, it has been found that diets rich in smoked or pickled foods containing preformed N-nitroso compounds or nitrites, respectively, (Neugut et al, 1996) or high consumption of salted foods or alcohol (Francheschi & LaVecchia, 1994) are closely correlated with an increased lifetime risk of developing gastric carcinoma. Conversely, diets high in raw fruits and vegetables and antioxidants such as vitamins C, E, and beta-carotene (Correa, 1995; Hwang et al, 1994) are strongly correlated with a reduction in the risk of gastric carcinoma (Correa, 1995).

Two histologically distinct types of gastric carcinoma have been described (Lauren, 1965). The distinction between intestinal and diffuse types of carcinoma continues to have relevance today, not only as a descriptive device but because the two types are thought to have different origins, risk factors, population distributions, and prognoses (see the section on epidemiology).

Intestinal-type gastric tumors are true adenocarcinomas. They are characterized by a proliferation of atypical glandular elements containing large numbers of mucin-containing goblet cells. There is commonly a loss of polarization with a varying amount of nuclear atypia in the cells lining these glandular formations. Histologically, the diffuse type of gastric carcinoma largely lacks recognizable glandular elements and consists predominately of stromal tissue. The hallmark of this type of tumor is the large number of signet-ring cells with deeply staining basophilic nuclei. Grossly, either of these tumors may be raised, flat, or ulcerated on endoscopic examination; in addition, intestinal-type tumors may be polypoid. The gross appearance of the lesion has little association with the true depth of invasion.

Noncarcinoma Gastric Malignancies

Although 92% to 98% of all gastric malignancies are adenocarcinomas, there are also three relatively uncommon tumors. The first of these is the primary gastric lymphoma. This represents 3% to 4% of all gastric malignancies and is predominately of the non-Hodgkin’s type. Gastric lymphomas arise from the mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue. The majority of these tumors are composed of B-lymphocytes and have long growth cycles, tending to remain within the stomach (Isaacson & Spencer, 1996). Primary T-cell lymphomas are much less common and tend to be more aggressive in their growth and spread. Finally, although histiocytic lymphomas and true Hodgkin’s disease of the stomach have been reported in the literature, the incidence of these tumors is vanishingly small. Like lymphoma at most other sites in the body, gastric lymphomas tend to be highly responsive to radiation and chemotherapy. Nonetheless, surgical excision, where possible, remains an important part of the therapeutic regimen.

Prognosis for all of these tumors is related to the stage of the disease at diagnosis and the histologic type of tumor. Early B-cell lymphomas are reported to have a 75% 5-year survival rate and late-stage T-cell lymphomas as low as a 32% 5-year survival rate (Aozasa et al, 1988).

Gastric leiomyosarcomas constitute approximately 1% to 2% of all gastric malignancies. These smooth muscle tumors can grow to large size, protruding primarily into the peritoneal cavity rather than into the lumen of the stomach. They are usually slow-growing tumors and it can be challenging to distinguish them from benign leiomyomas. Often the definitive diagnosis of malignancy can be made only after surgical resection, when the entire specimen is available for examination. In most cases, though, size is a good indicator of malignancy: tumors less than 4 cm are likely to be benign, those exceeding 6 cm malignant. Five-year survival rates after surgical excision have been reported to be as high as 55% for patients with smaller tumors but 30% for those with tumors greater than 8 cm.

The third major noncarcinoma tumor is the gastric carcinoid tumor. These endocrine tumors have been estimated to represent 3% of all gastric tumors. Although histologically similar, the gastric carcinoids are divided into two classes based on the prevailing gastric mucosa (Bordi, 1995). The first class is the classic carcinoid tumor, which is strongly associated with chronic atrophic gastritis and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. The hypersecretion of gastrin seen in these patients is thought to cause hyperplasia of enterochromaffin cells, resulting in carcinoid tumors. The second class of carcinoid-type tumors arises in histologically normal gastric mucosa without detectable antecedent endocrine abnormalities. These spontaneous or sporadic carcinoids are, in fact, true neuroendocrine carcinomas.

The gastritis-associated class of gastric carcinoid tumors is usually confined to the mucosa. Small tumors of this class are amenable to repeated endoscopic fulguration and treatment of the underlying gastric pathology, whereas larger tumors require surgical excision. The sporadic class is often poorly differentiated and more likely to metastasize to regional lymph nodes and distant sites. These tumors are rarely suitable for surgical intervention and have a markedly poor prognosis (Akerstrom, 1996).

EPIDEMIOLOGY

In the early part of this century, gastric cancer was the most common cancer in the United States. At that time it accounted for 35% of cancers in men and 22% of cancers in women (exceeded only by uterine cancer). Beginning around 1930, and continuing until the middle of the last decade, the incidence of stomach cancer in the United States fell to its currently stable rate of 3 per 100,000 women and 6 per 100,000 men (Boring et al, 1994). In 1994, 24,000 new cases of stomach cancer were reported. In that same year, there were 14,000 deaths attributed directly to it. The worldwide incidence of stomach cancer for men ranges from 35 per 100,000 in Japan to 6 per 100,000 in the United States, with the incidence for women averaging approximately half that of men. Within populations, rates for both sexes are higher among lower socioeconomic groups.

As the total incidence of gastric cancer declines worldwide, two apparently discrete populations of adenocarcinomas are becoming evident. The intestinal type (named for its histologic appearance) appears to be responsible for the majority of the decline. This is also the type that seems to be affected by environmental and dietary factors, because the risk of this type is reduced if a person moves from an area of high prevalence to one of low prevalence (Correa & Chen, 1994). The other type of tumor is called diffuse because of its predilection toward widespread involvement of the stomach. There is evidence linking this type of gastric cancer to genetic factors because its incidence has not been found to be associated with specific environmental factors (Elder, 1995). The incidence of diffuse-type gastric carcinoma has not changed significantly since its identification in 1965.

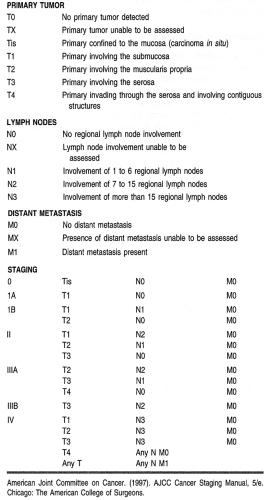

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

There have been several systems proposed to stage gastric carcinomas throughout the years. Currently, the system most commonly used by providers in the United States is the TNM system adopted by the American Joint Commission on Cancer (AJCC; Table 24-4). This staging system is useful in standardizing communications about cancers by grouping them by extent and severity, which roughly correlates with prognosis.

The single most important property of the primary tumor in determining prognosis is the depth of invasion. Thus, the

AJCC system classifies primaries as limited to the mucosa, extending to the serosa, or extending through the serosa (with or without involvement of contiguous structures). Regional lymph node involvement is divided into three groups corresponding to the number of regional lymph nodes found to be involved with tumor (see Table 24-4). Formerly classified as regional lymph nodes, the para-aortic, hepatoduodenal, pancreatic, and mesenteric lymph nodes are now classified as distant metastases.

AJCC system classifies primaries as limited to the mucosa, extending to the serosa, or extending through the serosa (with or without involvement of contiguous structures). Regional lymph node involvement is divided into three groups corresponding to the number of regional lymph nodes found to be involved with tumor (see Table 24-4). Formerly classified as regional lymph nodes, the para-aortic, hepatoduodenal, pancreatic, and mesenteric lymph nodes are now classified as distant metastases.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

History and Physical Examination

Gastric cancer is characteristically silent in its early stages. This contributes to the late stage at which most gastric cancers are diagnosed. Characteristic symptoms of gastric tumors such as early satiety, pain, and obstruction appear late in the course of the disease. These symptoms herald extensive involvement of the gastric body or pylorus. Occasionally, large extraluminal tumors may be palpable through the abdominal wall. Linitis plastica (leather-bottle stomach) is a classic sign associated with tumor infiltration throughout the stomach. It manifests as extremely early satiety resulting from a dramatic decrease in gastric distensibility and can often be palpated through the abdominal wall in the right upper quadrant.

Disease Course and Prognosis

Although advanced gastric cancer continues to have a uniformly poor prognosis, when gastric cancer is found and treated early, survival rates can be quite high. In 1993, Wanebo et al reviewed the American experience with gastric cancer from 1982 to 1992. The results of this study found that 5-year survival rates after surgical resection with curative intent depended on stage. Patients with stage I tumors had a 50% 5-year survival, with stages II, III, and IV carrying survival rates of 29%, 13%, and 3%, respectively. An important point revealed by this study was that more than two thirds of these patients had advanced disease (stage III or IV) at the time of diagnosis. Further, most of these patients did not receive radical lymph node dissection. Local recurrence occurred in 40% of patients and distant disease in 60%.

Reports on the long-term survival of patients undergoing resection for cure and intraoperative radiotherapy are becoming available for review from many centers. The 5-year survival rate was improved in patients with stage II, III, and IV disease from 62%, 37%, and 0%, respectively, to 83%, 62%, and 14%, respectively, using mid- to high-dose radiation (28 to 36 Gy) in selected patients (Abe et al, 1987).

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

The association between gastric cancer and chronic gastritis should alert providers to be on the lookout for neoplasia in patients with this condition. Routine upper gastrointestinal endoscopy with biopsy of suspicious areas has been shown to be of value in increasing early detection of gastric tumors. Recently a resurgence in the use of the upper gastrointestinal series has shown that double-contrast (barium and gas) radiographic examinations may be equivalent to endoscopy in distinguishing lesions with clearly malignant or clearly benign hallmarks, with follow-up endoscopic biopsy reserved for equivocal lesions (Halvorsen et al, 1996).

These findings have led to the use of mass screening programs as an adjunct to the identification of populations at high risk for the development of gastric cancer. Such programs have been successful in Japan, where the incidence of gastric cancer is many times higher than in most places in the West. Nationwide Japanese screening programs have succeeded in increasing the proportion of gastric cancers diagnosed in early stage (before extragastric spread) to approximately 30% in recent years (Sugimachi, 1993). To reproduce these results in the United States would require enormous resources, and because of the relatively low incidence of the disease the actual outcome might still be marginal.

The workup for newly identified gastric lesions should include computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Currently, CT is the preferred mode of abdominal

imaging in these cases. CT is relatively sensitive in detecting gastric wall infiltration, regional and distant lymph node abnormalities, and liver and spleen extension or metastases. However, like MRI, it lacks specificity, and both are unable to distinguish tumor involvement in normal-sized lymph nodes.

imaging in these cases. CT is relatively sensitive in detecting gastric wall infiltration, regional and distant lymph node abnormalities, and liver and spleen extension or metastases. However, like MRI, it lacks specificity, and both are unable to distinguish tumor involvement in normal-sized lymph nodes.

A relatively new technology is currently under evaluation for its value in examining gastric cancer. Endoscopic ultrasonic (EUS) probes can be applied to the mucosal surface of the stomach to determine the depth of tumor wall invasion. In certain cases even the regional lymph nodes can be examined with much higher accuracy than conventional transabdominal techniques. The widespread use of EUS, however, is limited by several factors. The EUS-equipped endoscopes are substantially larger than standard endoscopes, preventing their passage in patients already sensitive to upper endoscopy as well as patients with esophageal narrowing. Second, accurate interpretation of data from EUS equipment requires experience, which should improve as the technology matures and research data are disseminated (Miller et al, 1997).

TREATMENT OPTIONS, EXPECTED OUTCOMES, AND COMPREHENSIVE MANAGEMENT

Because gastric cancer is commonly diagnosed late in its course, often at a stage beyond which it can be successfully excised, and because of its historically poor response to chemotherapy and radiation treatment, research into prevention, mass screening, and identification of populations at risk for earlier detection and multimodal treatment regimens has intensified in recent decades (Patino, 1994).

Surgical Treatment

The first-line treatment of newly diagnosed gastric cancer continues to be surgical excision. In most cases, total gastrectomy with attempts to remove all involved tissues back to microscopically clean margins is the ultimate goal. Such an operation is currently not possible for the majority of patients presenting with locally advanced or metastatic cancers (Dalton & Eisenberg, 1994). The standard surgical treatment in Japan has differed from that in Western countries. Japanese surgeons are generally more aggressive, making use of systemic or radical lymph node dissection. The results of such surgery have yielded significant improvements in long-term survival rates in Japanese populations. Attempts to reproduce these results in Europe and the United States have not been as successful. At first, this was attributed to lack of familiarity with the surgical technique, but with increasing Western experience with radical gastrectomy, it seems that at least a portion of the Japanese success may be related to differences in the pathophysiologic variants of gastric cancer between Japan and Western countries (Maruyama et al, 1996). These differences may render the Japanese variant more susceptible to surgical excision.

The radical nature of surgical gastrectomy for gastric cancer (whether Japanese or Western) is fraught with intra- and postoperative dangers. These are often long procedures associated with massive intra- and extracellular fluid shifts. Patients are frequently malnourished and compromised by pulmonary or cardiac abnormalities. In addition, many of these operations involve removal of the pylorus or pancreas, leaving the patient prone to dumping syndrome or postoperative diabetes (Averbach & Jacquet, 1996). Clearly, such treatment requires detailed preoperative discussion to ensure that the patient understands both the nature of the disease process and the risks of the surgical resection.

Radiochemotherapeutics

To date, no chemotherapeutic agent, either alone or in combination, has proven effective as the sole treatment for gastric cancer. As a consequence, recent research has turned toward the use of chemotherapy in conjunction with surgery. Adjuvant combination chemotherapy has shown some efficacy after curative resection, but an overall survival advantage has yet to be demonstrated (Schipper & Wagener, 1996), and toxicity can be significant. These agents affect all rapidly proliferating cell populations. This includes bone marrow suppression, with its immunocompromising effect; gastrointestinal mucosal sloughing, with concomitant malabsorption; and impairments in wound healing and regeneration of skin appendages, resulting in, among other things, hair loss.

Another strategy under study is the use of neoadjuvant therapy before surgical resection (Fink et al, 1995). Downstaging of tumor preoperatively may make curative resection more feasible. Initial studies have indicated improved tumor-free survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and primary resection with lymphadenectomy versus resection and lymphadenectomy alone (Nakajima, 1995). Further studies in this area are required to define which patients will benefit from this technique.

Finally, true multimodal therapy for gastric cancer is under study at various centers (Jessup et al, 1993). This approach makes use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy to shrink the tumor, followed by resection and lymphadenectomy with intraoperative radiotherapy. Although this therapy is promising, long-term survival data are not yet available and are eagerly awaited.

TEACHING AND SELF-CARE

The importance of including the patient and family in the decision-making process cannot be overstated. The goal should always be for each team member to develop a comprehensive plan that includes all available options as well as recommendations. This plan is then communicated to the other team members, including the patient, preferably at interval multidisciplinary meetings. In this way, patients can make informed decisions and assume ultimate control over their disease. For further information on self-care, refer to the section at the end of this chapter.

Complementary Therapies

Early in the history of gastric cancer research, a link was identified between certain dietary components (eg, smoked meats, salted foods, alcohol) and an increased incidence of gastric carcinoma. More recently, an association between common dietary antioxidants and a decreased risk of gastric cancer has been studied. Experimental and epidemiologic data to this effect suggest that vitamin C and carotenoids may be of value in preventing gastric cancer when taken consistently in adequate amounts. The evidence in favor of vitamin E and selenium is not as strong (Kono & Hirohata, 1996). These data support the recommendation of a diet high in fresh fruits and vegetables, consistent with current FDA recommendations. There is littlecredible

support for megadosage or specific supplementation of these nutrients beyond that provided naturally (Buiatti & Munoz, 1996).

support for megadosage or specific supplementation of these nutrients beyond that provided naturally (Buiatti & Munoz, 1996).

Benefits in prevention of cancer have also been ascribed to various teas and native foods. The current literature indicates that these benefits are probably a result of the combined effect of lifestyle, balanced diets, and varying population risks rather than any single dietary substance.

REFERRAL POINTS AND COMMUNITY RESOURCES

Once diagnosed, patients and their family members need evaluation by the health care team. At this point, patients often require consultation with an oncologist, surgeon, and gastroenterologist. To this group may be added a radiologist, radiation oncologist, and possibly a dietitian. At the same time, the patient will require the work of social services for assistance in coming to grips with the diagnosis of cancer. A spiritual counseling team can be invaluable, depending on the patient’s support system and life-view. At this point introduction to local and national support organizations or even other local cancer patients may prove to be essential for both the patient and significant others to help them deal with the feelings of isolation and information overload commonly encountered. Other community resources can be found at the end of this chapter.

CLINICAL PEARLS

Gastric cancer is difficult to diagnose.

The physical examination may be unrewarding.

Gastric cancer must be in the differential diagnosis of chronic abdominal pain, unexplained nausea, unexplained vomiting, and upper intestinal obstruction or gastric outlet obstruction.

Screening for gastric cancer is indicated for chronic atrophic gastritis and chronic gastric ulcer.

References

Abe, M., Shibamoto, Y., Takahasi, M., et al. (1987). Intraoperative radiotherapy in carcinoma of the stomach and pancreas. World Journal of Surgery, 11, 459–464.

Akerstrom, G. (1996). Management of carcinoid tumors of the stomach, duodenum and pancreas. World Journal of Surgery, 20, 173–182.

Aozasa, K., Euda, T., Kurata, A., et al. (1988). Prognostic value of histologic and clinical factors in 56 patients with gastrointestinal lymphomas. Cancer, 61, 309–315.

Averbach, A.M., & Jacquet, P. (1996). Strategies to decrease the incidence of intra-abdominal recurrence in resectable gastric cancer. British Journal of Surgery, 83, 726–733.

Bordi, C. (1995). Endocrine tumors of the stomach. Pathology, Research and Practice, 191, 373–380.

Boring, C.C., Squires, T.S., Tong, T., et al. (1994). Cancer statistics. CA Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 44, 7–26.

Buiatti, E., & Munoz, M. (1996). Chemoprevention of stomach cancer. Lyon, France: IARC Scientific Publications; 136:35–39.

Correa, P. (1995). The role of antioxidants in gastric cancer. Critical Reviews of Food Science and Nutrition, 35, 59–64.

Correa, P., & Chen, W. (1994). Gastric cancer. Cancer Surveys, 19-20, 55–76.

Dalton, R.R., & Eisenberg, B.L. (1994). Rationale for the current surgical management of gastric adenocarcinoma. Oncology, 8, 99–105.

Dobrilla, G., Benvenuti, S., Amplatz, S., et al. (1994). Chronic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and Helicobacter pylori in gastric cancer: Putting the pieces together. Italian Journal of Gastroenterology, 26, 449–458.

Elder, J.B. (1995). Carcinoma of the stomach. In W.S. Haubrich, F. Schaffner (Eds.). Bockus gastroenterology, 5th ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 859–874.

Fink, U., Stein, H.J., Schumacher, C., et al. (1995). Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for gastric cancer: Update. World Journal of Surgery, 19, 509–516.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree