INTRODUCTION

“Love conquers everything except poverty and toothaches.” Mae West, Irish Times

Unlike much of the rest of this book, which assumes health care professionals already have the skills and knowledge to provide treatment, but not their normal equipment, this section describes dental diagnoses and basic treatments in considerably more detail. Treating dental emergencies is a critical skill, especially in situations of resource scarcity. Yet, even though dental emergencies are common, painful, and may occur with little or no warning, non-dentists rarely have in-depth knowledge about their treatment options.

BASIC DENTAL ANATOMY

When annotating the patient’s medical record or communicating with another health care provider, such as a dentist, use a picture in the medical record. When communicating with another provider by phone or radio, describe the type and position of the tooth.

Teeth are either baby or adult teeth.

They are either maxillary or mandibular, and are on either the right or the left side of midline. Midline is the space between the front two teeth (incisors).

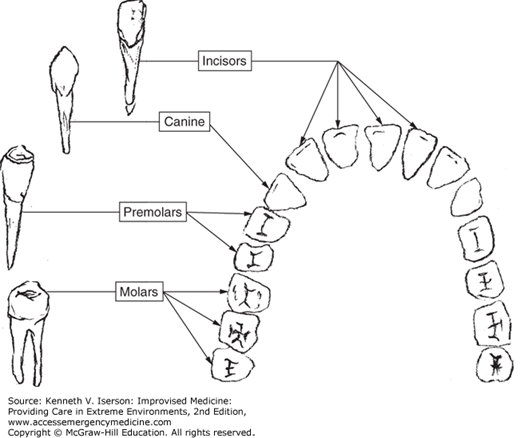

There are four types of teeth (Fig. 26-1).

Those with one root are:

Incisors

Canines

Premolars

One type has two or more roots:

Molars

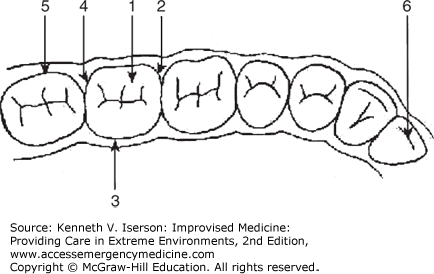

The following names describe the surfaces of the teeth. The number corresponds to those in Fig. 26-2.

Occlusal surface: The chewing surface of molars and premolars.

Mesial surface: The surface nearest the midline of the body (medial).

Lingual surface: The surface nearest to the tongue in the lower jaw; it is called the palatal surface in the upper jaw.

Distal surface: The surface furthest from the midline.

Buccal surface: The surface nearest to the lips and cheek.

Incisal edge: The incisors and canines have a cutting edge instead of an occlusal surface.

Proximal surfaces (not shown): Surfaces that are close together, that is, the mesial surface of one tooth may touch the distal surface of the next tooth.

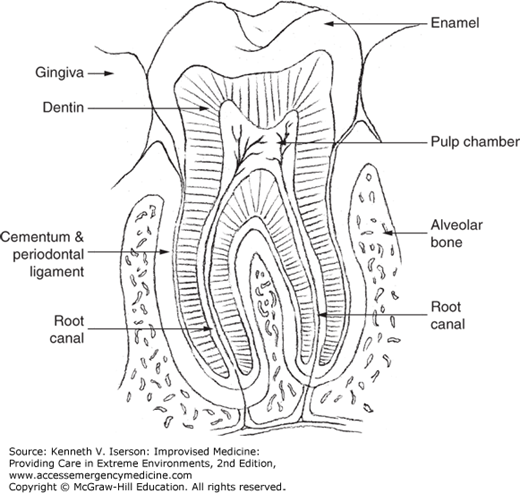

Tooth problems may involve any of the tooth’s three layers or their supporting structures (Fig. 26-3).

The part of the tooth above the gum line is the crown. Covered with hard enamel, the crown protects the other layers. Do not confuse the term “crown” as part of the tooth with the dentist’s “crown” (also known as a “cap”), which is a dentist-made covering for a tooth.

Softer than enamel but about the same density as bone, dentin is a yellowish substance that lies under the enamel and surrounds the tooth’s pulp cavity.

The “heart” of the tooth, the pulp cavity contains nerves and blood vessels. Generally, it extends from the gum line to the end of the root. The vessels and nerves then continue into the alveolar bone of the mandible or maxilla.

Every tooth has tight attachments to the bone and gums. These are the periodontal ligaments. They must be severed below the gum line when removing a tooth.

PREVENTION/CLEANING

The primary culprit in dental pathology is plaque: the soft, white or yellow layer that sticks to the teeth. Consisting primarily of bacteria, plaque also contains dried saliva, blood cells, and food particles. It accumulates at the base of the teeth, in the grooves of the tooth’s occlusal surfaces, and in the spaces between the teeth. The simplest way to remove plaque from tooth surfaces when it is still sticky is to wipe it off with a cloth. A common alternative method is to thoroughly chew a green twig from a nonpoisonous plant until it becomes soft and fibrous. Use the twig’s end to brush the teeth and gums. Eventually, this sticky, mineralized deposit (calculus) hardens and requires formal removal. At that point, it must be scraped off with a thin, bent metal tool. Dentists use a “scaler” or “dental pick.” Alternatively, practitioners can use a small blunt needle to make a suitable instrument. First, cut off and sand the sharp end of the needle. Then, bend the end and attach it to a small syringe, which becomes a handle.

PAIN WITHOUT TRAUMA

Many types of lesions can cause pain and swelling in the mouth and face.2,3 Table 26-1 provides a brief overview of the presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of various causes of mouth and jaw pain.

| Presentation | Diagnosis | Definition | Complications | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain, erythema, and swelling. | Cellulitis | Diffuse soft tissue bacterial infection | Regional spread | Antibiotics and root canal or extraction |

| Jaw hurts when touched. Teeth do not fit together properly or difficulty opening mouth. Recent trauma. | Mandible fracture | Mandible broken; may communicate using mouth (open fracture) | Malocclusion, infection, continued pain | Soft diet, wire jaw (stabilization) |

| Swelling under or behind jaw, worsens when hungry or smells food. | Salivary gland infection or obstruction | Usually stone in salivary duct; occasionally tumor | Infection, abscess, continued pain | Increase salivation: suck on tart candy, stone, etc. Antibiotics, if infected |

| Non-tender swelling in front of ear or on neck. | Branchial cleft cyst | Residual from embryological development | Infection (rare) | Surgery, if desired |

| Tender swelling in front of both ears with fever. | Mumps | Viral infection involving parotid glands | Orchitis in older males | Isolate from nonimmunized individuals, provide support |

| Swelling present for a long time. It is firm and does not seem to get better. | Tumor | Cancer | Local tissue destruction and metastatic disease | Biopsy. Excision, radiation, or chemotherapy, as indicated |

| Gums between teeth have died and are no longer pointed. Foul odor from mouth due to pus and blood around teeth. | Necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (Trench mouth, Vincent’s angina or stomatitis) | Infection from mouth flora due to poor oral hygiene and life situation | Pain and decreased oral intake, continued gum deterioration and tooth loss | Clean/debride area. Gentle daily brushing; qh warm salt H2O or bid 1.5% H2O2 or 0.12% chlorhexidine rinses. Improve diet. Antibiotics if thorough teeth cleaning not available |

| Sore or small abscess near root of bad tooth. | Gum bubble | Extension of periapical abscess through a fistula | Cellulitis | Incision/drainage and root canal or extraction |

| Pain and clicking sound from in front of ear when moving jaw, including when chewing. | Temporo-mandibular joint (TMJ) pain | Degeneration of the TMJ from trauma, arthritis, etc. | Continued pain, decreased oral intake, sleeplessness, depression | Analgesics, bite guard, local injections, soft diet. Surgery only as last resort |

The most common painful oral lesions are aphthous ulcers (canker sores), traumatic ulcerations, and cold sores (Herpes labialis). While suitable treatment is “tincture of time,” they may heal faster with less pain if they are covered, at least for several hours, with any lip balm or salve such as petroleum jelly—until they are licked off. An equally effective and possibly longer-lasting covering is cyanoacrylate (e.g., commercial Super Glue and multiple brands for medical wound closure).4 (See below for more details on how to use it.)

Patients with multiple intraoral lesions, including mucositis in immunocompromised (e.g., cancer, AIDS) patients, may be helped by taking a mouthful of “magic mouthwash” every 2 to 3 hours, swishing it around in their mouths, and spitting it out. Make the solution using any of a dozen formulations. The most common basic elements are a 1:1:1 combination of (by volume) diphenhydramine (e.g., Benadryl) elixir, viscous lidocaine 2%, and a liquid antacid. Other common ingredients are tetracycline or erythromycin (that may be helpful with bacterial infections in the mouth) or, especially for cancer and immunocompromised patients, a steroid such as dexamethasone or hydrocortisone, or nystatin. One common formula uses 4 parts nystatin suspension 100,000 units/mL, 3.5 parts diphenhydramine elixir, and 1 part lidocaine viscous 2%. If the solution is made with a substance such as Kaopectate or sucralfate (Carafate), the ingredients will adhere to surfaces, and so it can be applied directly to the intraoral lesions.

If standard oral agents are not available, treat oral candidiasis (thrush), a very common oral lesion, by having the patient suck on a vaginal anti-yeast suppository or apply a vaginal anti-yeast cream to the lesion four times a day (qid).

Painful gums can result from poor oral hygiene, infections, inflammation over an erupting tooth, or dental appliances such as orthodontics.

To avoid or treat inflamed gums resulting from poor oral hygiene, patients gently brush their teeth and gums and floss with dental floss or a substitute. They also can rinse their mouth with warm saltwater (0.5 tsp table salt in 4 oz of warm potable water) or a solution containing one part potable water and one part 3% hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) several times a day.5

More serious, and much more painful, is necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis, also known as trench mouth, Vincent angina or stomatitis, or necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis. This serious but treatable disease of the gums and deeper tissues usually begins abruptly; the patient may be febrile. The gums are very painful and bleeding, with punched-out ulcers covered with a gray pseudomembrane. Patients have extremely foul breath, pain on talking or swallowing, and may have lymphadenopathy. Treatment consists of gently debriding the area over several days. Wipe the gums with cotton or other absorbent cloth soaked in 3% H2O2. Use one part H2O2 to five parts water in children. Then scrape off the larger pieces of tartar. Have the patient gently brush their teeth and gums daily with a soft brush and rinse every waking hour with warm saltwater or twice a day with 1.5% H2O2 or 0.12% chlorhexidine. For the pain, use nonsteroidal analgesics and, if available, local anesthetic on the gums—after drying them. Encourage patients to avoid spicy foods and to improve their diet. They may need to be on a liquid or soft diet for a while. They should drink lots of liquids, take supplemental vitamin C, and avoid smoking and chewing betel nuts or tobacco. If thorough cleaning and debridement is not available, give oral penicillin VK 500 mg, erythromycin 250 mg, or tetracycline 250 mg q6hr until 72 hours after the symptoms resolve.

Pericoronitis occurs when inflammation develops around a partially erupted (usually molar) tooth. A flap of gingival tissue remains over the tooth, which traps food particles and is irritated by chewing. Local swelling may cause enough irritation to make it difficult to fully open the jaw. To treat this, gently irrigate the area under the flap. Have the patient rinse his or her mouth with warm saltwater for 10 minutes every 2 hours while awake. If no dentist will be available within a few days, excise the flap over the tooth.

If orthodontic appliances are causing pain, use a blunt object, such as a tongue depressor or pencil eraser, to bend the wire away from the gum. If it cannot be bent, cover it with wax (candle or dental) or a tiny piece of cloth or cotton. Paradoxically, chewing (preferably sugarless) gum reduces the general pain caused by orthodontic appliances.

Most cases in which non-dentists will need to provide emergency dental treatment will be for toothaches. While teeth can be transiently painful for a number of reasons, constant, often excruciating, pain in a tooth constitutes a toothache. Generally, toothaches are caused by fractures or decay (caries; causes cavities) that extends into the tooth’s central area (pulp). A tooth in which the pulp is no longer healthy often has a history of persistent, often severe and throbbing, pain after eating hot or cold food. Cold stimulus causes prolonged pain, but the tooth is generally not sensitive to palpation.

To locate the painful tooth, have the patient point to it or gently tap on teeth in the affected area with an instrument until the patient experiences discomfort. When a tooth is tender to percussion, it is likely that there is a periapical abscess. The affected tooth can also be located by touching it with the corner of an ice cube. A normal tooth will briefly feel the cold stimulus; a diseased, but salvageable, tooth with some healthy pulp may have slightly more prolonged pain after withdrawal of the ice and is not usually sensitive to percussion. Treat them as described in the subsequent paragraphs. Be sure to check adjacent teeth for their relative sensitivity to percussion and cold. An unsalvageable tooth generally has no sensation to percussion or to a cold stimulus.

Table 26-2 provides a method of diagnosing about 90% of non-trauma-related toothaches. However, for the clinician faced with a patient’s sore tooth, this table may not help in differentiating between an abscess and pulpitis. (Pulpitis is inflammation of the pulp, or center, of the tooth that contains vessels and nerves). To make this differentiation easier, remember the mnemonic PAIN to indicate that pain on Percussion (the tap test on the tooth) = Abscess (periodontal or periapical), while pain with Ice (test the tooth by touching ice to it) = Nerve pain (pulpitis).

| Presentation | Diagnosis | Definition | Complications | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Pain after eating or drinking Caries: present Cold test: negative Tap test: negative Biting pain: negative | Caries (cavity) | Hole in tooth enamel | Pulpitis | Clean hole, filling (temporary) |

Pain after eating or drinking Caries: present; previously filled Cold test: negative Tap test: negative Biting pain: negative | Lost or broken filling | Caries, previously filled, with lost or broken filling | Pulpitis | Clean hole, filling (temporary) |

Pain on eating hot, cold, or sweet food Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|