Epidemiology of cardiac arrest

In 2006, coronary heart disease accounted for 1 of every 6 deaths (a total of 425,425) in the United States and one-third of these deaths occurred within 1 h of symptom onset. In Europe, the annual incidence of emergency medical system (EMS)-treated, out-of-hospital cardiopulmonary arrest (OHCAs) for all rhythms is 40 per 100,000 population, with ventricular fibrillation (VF) arrest accounting for about one-third of these. However, data from recent studies indicate that the incidence of VF is declining: it was reported most recently as 23.7% among EMS-treated arrests of cardiac cause. Survival to hospital discharge is 8–10% for all-rhythm and around 21–27% for VF cardiac arrest; however, there is considerable regional variation in outcome.

The incidence of in-hospital cardiac arrest (IHCA) is difficult to assess because it is influenced heavily by factors such as the criteria for hospital admission and implementation of a Do Not Attempt Resuscitation (DNAR) policy. There are an estimated 200,000 treated IHCAs each year in the United States—approximately one per 1000 bed days. Of these patients undergoing CPR, 17.6% survive to hospital discharge and 13.6% have a favourable neurological outcome (Cerebral Performance Category (CPC) 1 or 2). Many patients sustaining an IHCA have significant comorbidity, which influences the initial rhythm and, in these cases, strategies to prevent cardiac arrest are particularly important.

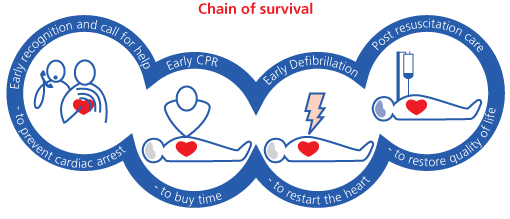

The chain of survival

The key steps for improving survival are shown in the chain of survival (Figure 1.1).

Early recognition and call for help

Out-of-hospital, early recognition of the importance of chest pain will enable the victim or a bystander to call the EMS and the victim to receive treatment that may prevent cardiac arrest. In-hospital, early recognition of the deteriorating patient who is at risk of cardiac arrest and a call for the resuscitation team or medical emergency team (MET) will enable treatment to prevent cardiac arrest. If cardiac arrest occurs, early recognition and a call for help are essential. Agonal breathing (gasping) often occurs immediately after cardiac arrest and is often mistaken for a sign of life—this can cause delays in starting CPR.

Early CPR

If cardiac arrest occurs, the victim will be unconscious, unresponsive and not breathing or not breathing normally (agonal breathing). Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) with chest compressions and ventilation of the victim’s lungs will slow the deterioration of the brain and heart. Bystander CPR doubles the chances of long-term survival. Interruptions to chest compressions must be minimised and should occur only briefly during defibrillation attempts and rhythm checks.

Early defibrillation

Ventricular fibrillation (VF) is the commonest initial rhythm after a primary cardiac arrest although this often deteriorates to a non-shockable rhythm by the time it is first monitored. Early defibrillation can be effective at restoring a circulation. Public Access Defibrillation (PAD) programs using automated external defibrillators (AEDs) enable a wide range of rescuers to treat OHCA caused by VF. Most IHCAs tend to have an initial rhythm of pulseless electrical activity (PEA) or asystole but most survivors are among those with VF arrest. Hospital staff should therefore be trained and authorised to use a defibrillator (AED or manual) to enable the first responder to a cardiac arrest to attempt defibrillation when indicated, without delay.

Post resuscitation care

Return of a spontaneous circulation (ROSC) is an important phase in the continuum of resuscitation; however, the ultimate goal is a patient with normal cerebral function, a stable cardiac rhythm and normal haemodynamic function, so that they can leave hospital in good health and at minimum risk of a further cardiac arrest. The quality of the treatment given in the post-cardiac arrest phase will influence outcome—there is considerable inter-hospital variation in outcome among patients admitted to an intensive care unit after cardiac arrest (Box 1.1).