BLUNT AND PENETRATING NECK INJURY

The complex anatomical relationships within a small area make the diagnosis and management of both penetrating neck injuries (PNI) and blunt neck injuries (BNI) challenging. Radiographic evaluation continues to evolve, with a shift from invasive to noninvasive diagnostics. Despite advances in both diagnosis and therapeutics, the optimal management of neck injuries remains a matter of active investigation.

PENETRATING INJURIES

Epidemiology

Firearms are responsible for approximately 43%, stab wounds for 40%, shotguns for 4%, and other weapons for 12% of all PNI.1 Overall, about 35% of all gunshot wounds (GSW) and 20% of stab wounds (SW) to the neck cause major injuries, but only 16% of GSW and 10% SW require surgical therapy. Even though transcervical GSWs cause major injuries in 73% of victims, only 21% require surgery.2 The most common injury after PNI is vascular.1,3 Spinal cord injuries and injuries to the aerodigestive tracts and various nerves are also common.1

Anatomical Zones

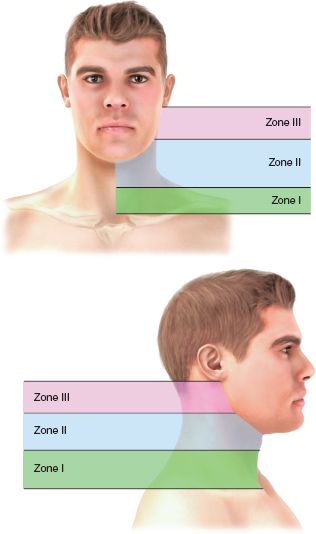

The neck can be divided into three anatomical zones for evaluation and therapeutic strategy purposes (Fig. 26.1). Zone I comprises the area between the clavicles and the cricoid cartilage. Criticial structures include the innominate vessels, the origin of the common carotid artery, the subclavian vessels and the vertebral artery, the brachial plexus, the trachea, the esophagus, the apex of the lung, and the thoracic duct. Surgical exposure in zone I can be difficult because of the presence of the clavicle and bony structures of the thoracic inlet. Zone II comprises the area between the cricoid cartilage and the angle of the mandible and contains the carotid and vertebral arteries, the internal jugular veins, trachea, and esophagus. This zone is more accessible to clinical exam and surgical exploration than the other zones. Zone III extends between the angle of the mandible and the base of the skull and includes the distal carotid and vertebral arteries and the pharynx. The proximity to the skull base makes zone III structures less amenable to physical exam and difficult to explore. Overall, zone II is the most commonly injured area (47%) after PNI, followed by zone III (19%) and I (18%).4 In 16%, injuries will involve more than one zone.1

FIGURE 26.1. Surgical zones of the neck: zone I is between the clavicle and the cricoid, zone II between the cricoid and the angle of the mandible, and zone III is between the angle of the mandible and the base of the skull.

Airway Management

Approximately 8%–10% of patients with PNI present with airway compromise.2,5–7 In patients with laryngotracheal injuries, about 30% require the establishment of a secure airway in the ED.7 Airway compromise may be due to direct trauma, airway edema, or from external compression by a large hematoma. Small penetrating airway injuries by knife or low-velocity bullets are less likely to result in respiratory problems than laryngotracheal transections or high-velocity GSW.1

Air bubbling through a neck wound is pathognomonic of airway injury. Firm manual compression over the wound reduces the air leak and will usually improve oxygenation. Orotracheal intubation in the ED after PNI should be performed by the most experienced provider, recognizing the potential need for emergent surgical airway. The severity of respiratory distress, hemodynamics, the size and site of hematoma, presence of a large air leak, and the experience of the trauma team will determine the best technique. For patients with large neck hematomas who are not in respiratory distress, fibreoptic intubation may be safe. However, this procedure requires experience and skill and can be performed only semielectively; there is a reported failure rate of approximately 25%.7

The use of neuromuscular paralysis during intubation in the ED after PNI remains controversial. Orotracheal intubation without neuromuscular paralysis increases difficulty. Coughing or gagging worsens bleeding. However, pharmacologic paralysis may prove dangerous if the cords cannot be visualized secondary to distorted anatomy from a compressing hematoma or edema. Loss of the muscle tone after paralysis may further displace the airway, leading to total obstruction. In a recent review of PNIs, 21% required ED airway. In 12% of patients, orotracheal intubation failed, requiring emergent cricothyroidotomy.8

In the presence of large midline hematomas, cricothyroidotomy is difficult and may be associated with severe bleeding. Large laryngotracheal wounds can be intubated under direct view into the distal transected segment through the neck wound itself. The distal airway should be grasped with forceps before insertion of the tube to avoid complete tracheal transection or retraction into the mediastinum.

Initial Control of Hemorrhage

External bleeding due to PNI is controlled by direct pressure in most cases. However, bleeding from behind the clavicle, near the base of the skull, or from the vertebral artery is often difficult to control by external pressure. Digital compression with an index finger through the wound can help. Ballon tamponade techniques may also help.2,9 A Foley catheter is inserted into the wound and advanced as far as possible without resistance. The balloon is then inflated until the bleeding stops or moderate resistance is felt. If the bleeding continues, the balloon is deflated, and the catheter is slightly withdrawn and reinflated. Substantial bleeding through the catheter is suggestive of distal bleeding and indicates the need for repositioning.

With periclavicular injuries, bleeding can occur into the thorax. In these cases, the Foley catheter is advanced into the chest through the wound, the balloon inflated, and the catheter pulled back until resistance is felt, compressing the bleeding vessels against the first rib or the clavicle. Traction is maintained with a clamp placed on the catheter just above the skin until operative exposure is obtained.9 Blind clamping of bleeding is rarely successful and may cause vascular or nerve damage.

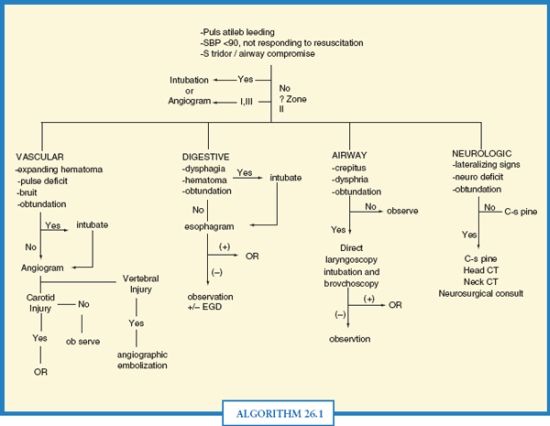

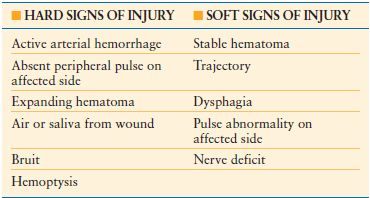

Physical examination, preferably according to a written protocol (Algorithm. 26.1; Table 26.1), remains the most reliable initial diagnostic tool. Physical exam should be systematic and specifically directed to look for signs or symptoms of injuries to the vital structures. Signs can be classified into “hard” signs, which are pathognomonic of injury, and “soft” signs, which are suspicious but not diagnostic of injury1,10 (Table 26.2). In GSW, the most common sign is a moderate or large hematoma (20.6%). Following SW, painful swallowing (14.3%) and hemo/pneumothorax (13.5%) are most common.1 Subcutaneous emphysema occurs in about 7% of PNIs.1 This may be secondary to laryngotracheal or esophageal injury or an associated pneumothorax. Only about 15% of patients with soft signs have substantive laryngotracheal injury.1

ALGORITHM 26.1 Protocol of examination and initial evaluation of penetrating neck injuries. (Modified from Demetriades D, Salim A, Brown C, et al. Neck injuries. Curr Probl Surg. 2007;44(1):13–85 with permission.)

TABLE 26.1

HARD AND SOFT SIGNS OF INJURY AFTER PENETRATING NECK TRAUMA

In one of the largest series of patients with PNI, patients with hard signs of vascular injury required operation as compared to about 3% with soft signs.1 Of the patients with soft signs who underwent angiographic evaluation, 23.5% had an angiographic abnormality, but only 3% required operation.1

Evaluation for Nervous System Injuries

Although the diagnosis and management of spinal cord injuries are covered elsewhere in this text, the initial evaluation warrants mention. The clinical examination after PNI should include assessment of the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score, localizing signs, pupils, cranial nerves (VII, IX-XII), spinal cord, brachial plexus (median, ulnar, radial, axillary, and musculocutaneous nerves), the phrenic nerve, and the sympathetic chain (Horner’s syndrome). The GCS may be abnormal from ischemia secondary to a carotid injury or associated intracranial missile injury.

The Value of a Protocolized Approach to Physical Exam

A protocolized exam provides reliable identification of the majority of major injuries requiring therapeutic intervention.1,4 In one large prospective study with predominantly SW to the neck, 80% was found to have no symptoms or signs suggestive of vascular or aerodigestive injuries and were selected for nonoperative management. Only two of the observed patients (0.7%) required semielective operation for vascular injuries. In both cases, a bruit was detected the day after admission, and angiography demonstrated an arteriovenous fistula.4

In another prospective study of predominantly GSW, 71.7% had no clinical signs suggestive of vascular injury. None of these patients required operation or other form of therapeutic treatment (negative predictive value [NPV] 100%). Angiography was performed on 127 of the asymptomatic patients from this series, revealing 11 vascular injuries (8.3%), but none required intervention. None of the patients without signs or symptoms of aerodigestive injuries had an injury requiring operation (NPV 100%).

For patients with soft signs of injury, including concerning wound proximity, additional investigations are warranted. The specific protocol will vary based on institutional capabilities. The utility and limitations of the respective possible investigations following PNI are outlined in the following sections.

INVESTIGATIONS

Plain Chest and Neck Films

Chest films should be obtained in all stable patients with penetrating injuries in zone I or any other wounds that might have violated the chest cavity. Approximately 16% of GSWs and 14% of stab wounds to the neck have an associated hemo/pneumothorax.1 Other important radiological findings include a widened upper mediastinum suspicious for thoracic inlet vascular injury, subcutaneous emphysema, fractures, and missiles.

Angiography

Angiographic evaluation of the neck vessels following PNI once was standard.–1012 However, angiography in asymptomatic patients is low yield and offers no benefit over physical exam combined with noninvasive investigations.1,2,4,6,13–18 In a prospective study, asymptomatic patients were evaluated angiographically at a cost of $254,000 and 11 vascular injuries not requiring treatment were identified. Additionally, the combination of clinical examination and Color Flow Doppler (CFD) in this series diagnosed all vascular injuries.1 In another prospective study, 80% were selected for nonoperative management. Angiography was performed on only seven patients. There were no deaths or substantial complications. Early and late follow up demonstrated no substantial missed vascular injuries.4

Some studies have suggested that clinically occult, angiographically identified injuries have a benign prognosis and require no treatment.19,20 There is, however, concern regarding the natural history of such lesions and adequacy of physical exam for their detection. Although the absence of hard clinical signs reliably excludes substantial injuries requiring treatment, the presence of soft signs of vascular injury does not reliably differentiate patients who require operation.1,15 In one study, a subgroup of 34 patients with soft signs of vascular injury had angiography.1 Eight (23.5%) had vascular injuries but only one (3%) needed intervention. Some form of imaging is needed to follow identified injuries. Several noninvasive modalities are alternatives.

Color Flow Doppler

CFD has been suggested as a reliable alternative to angiography in the evaluation for vascular injuries following PNI.1,2,15,21–25 In a prospective study conducted by Demetriades et al., CFD diagnosed 10 of 11 angiographically detected injuries and missed only one small intimal injury, which did not require subsequent operation. In a subsequent prospective study with 25 patients with PNI evaluated by both angiography and CFD, Corr et al.22 demonstrated the same results. CFD is operator-dependent and may miss injuries of the proximal left subclavian artery, the internal carotid artery near the base of the skull, and the vertebral artery under the bony vertebral canal.

Computed Tomography

Computed tomography (CT) with adequately phased IV contrast protocols has become a useful tool in the evaluation of PNI, especially in GSW, and has become the first line investigation in hemodynamically stable patients with PNI to the neck in many centers. Prior to CT, the entry and exit of the bullet should be marked with radioopaque markers. In addition, 3-mm CT cuts should be obtained between the markers or between the entry and the retained bullet. Identifying bullet trajectory may help in determining the need for further invasive investigations, such as angiography or endoscopy. Patients with trajectories away from the major structures require no further evaluation.16,26–29

Munera et al.27,28 compared conventional angiography and helical CT angiography. CT angiography had a sensitivity of 90%, specificity 100%, PPV 100%, and NPV 98%. Another study of 175 patients also suggested CT is a valuable investigation for the evaluation of suspected arterial injuries of the neck.28 CT may have some important limitations, however, particularly when images are obscured due to artifact from metallic fragments or excessive air in the soft tissues.29 In these cases, conventional angiography may be necessary for adequate exclusion of vascular injury.

CT also provides information about the site and nature of associated spinal fractures, involvement of the spinal cord, the presence of fragments in the spinal canal, or hematoma compressing the cord. A brain CT scan is also indicated for patients with PNI and unexplained central neurological deficits. In these instances, CT should be used to evaluate for possible anemic infarction secondary to a carotid artery injury or an associated direct brain injury due to a missile fragment.

Esophageal Studies

Esophageal studies are indicated in stable patients with soft signs and in cases with a CT scan bullet trajectory near the esophagus. Contrast esophagography is commonly used but may miss small injuries. Armstrong et al.30 reported that contrast esophagography diagnosed only 62% of perforations, compared to100% with rigid esophagoscopy. The technique of esophagography may be important to minimize false-negative studies. Esophagography should first be performed with a water-soluble contrast, such a gastrographin. If no leak is identified, the study is repeated with thin barium, as gastrographin alone may miss small injuries.31

Esophagoscopy, if performed by an experienced endoscopist, may also be useful. Flexible endoscopy has been shown to have a NPV of 100% but a positive predictive value of only 33%.32,33 This is the study of choice in many centers for patients who cannot undergo esophagogram because of a depressed level of consciousness or during intraoperative evaluations. Rigid esophagoscopy may be superior to flexible endoscopy in the evaluation of the upper esophagus, but requires general anesthesia, and many surgeons are not experienced with the technique.34

Studies for Laryngotracheal Evaluation

Indications for laryngotracheal evaluation include proximity injury, soft signs suspicious of airway injuries (minor hemoptysis, hoarseness, and subcutaneous emphysema) or CT scan findings showing a bullet tract near the larynx or trachea.

Flexible fibreoptic endoscopy is the investigation of choice, and it can be performed in the ED. The most common abnormal findings are blood or edema in the laryngotracheal tract and vocal cord dyskinesia.1 GSWs are more likely to be associated with abnormal findings than SW (24.6% vs. 8.5%). However, only 20% of patients with abnormal findings require operation.1,34

Operative versus Nonoperative Management of Penetrating Injuries

For many years, mandatory operation for all patients with penetrating injuries of the neck that violated the platysma was standard. The rationale was that clinical examination was not reliable. In addition, it has been suggested that routine operation avoids expensive investigations and does not prolong hospital stay.35 Routine surgical exploration is associated with an unacceptably high incidence of unnecessary operations, ranging from 30% to 89%.35,36 Improved appreciation of the reliability of physical exam, combined with noninvasive diagnostic capabilities, has resulted in the use of selective nonoperative management at most centers.1,4,14,15,19,37,38

GSWs are associated with a higher incidence of substantial injuries requiring operation than SW. However, more than 80% of GSW to the neck does not require an operation, and there is strong evidence that these patients can be identified and spared an unnecessary operation.1,4,6,15,39,40

Transcervical GSWs are associated with a much higher incidence of substantial injuries than GSW that have not crossed the midline (73% vs. 31%).15 It has been suggested that all such patients undergo exploration, irrespective of clinical exam.41 However, many of these injuries, such as spinal cord or nerve injuries, do not require operation. In one prospective study of transcervical GSW, 73% of patients had injuries to vital structures, but only 21% required operation.15,34 Several studies have demonstrated that CT angio with thin cuts can reliably identify those patients who do not need further investigation or those who might benefit from specific studies.16,17,29–32,42

BLUNT INJURIES

Although physical exam and initial management priorities for BNI are much the same as for penetrating injuries, a knowledge of the differences in injury patterns is essential for prompt diagnosis and management. We will focus on BNI causing laryngotracheal, pharyngoesophageal, and vascular trauma.

Epidemiology

Although BNI is common, when cervical spine injuries are excluded, injuries to the remaining structures are rare. Injuries to the aerodigestive tract are typically from direct force to the anterior neck.43,44 Both laryngotracheal and pharyngoesophageal are rare after BNI, occurring in 0.04%–0.3% of patients.45,46 Similarly uncommon, but far more lethal, are blunt cerebrovacsular injuries, including injury to the vertebral and carotid arteries. With increased appreciation and availability of noninvasive diagnostics, the rates of these injuries are now between 1.0% and 2.0%.47–54

INVESTIGATIONS

Plain x-rays of the neck and chest are a rapid noninvasive method of evaluating patients with suspected BNI. Cervical or mediastinal emphysema has been reported in as many as 95% of aerodigestive injuries. Cervical spine fractures are a risk factor for blunt cervical vascular injury.47,50 In particular, vertebral artery injuries are associated with complex cervical spine fractures with subluxation, extension into the foramen transversarium, or fractures to the higher cervical vertebrae.48

CT and Oral Contrast Studies

CT is the cornerstone of initial imaging for blunt trauma patients. Though aerodigestive injuries are best visualized with panendoscopy, CT and contrast studies may help patients with a high suspicion of injury. For laryngotracheal injuries, CT is more sensitive than plain radiographs in identifying cervical emphysema. CT also identifies small amounts of cervical air or contained leak after pharyngoesophageal injury. Gastrograffin or barium swallow will reveal an abnormality in 75%–100% of cases of cervical esophageal perforation.55

At many trauma centers, CT angiography has emerged as the initial screening test of choice for blunt carotid and vertebral injuries.53,56–61 However, there remain conflicting results as to the utility of CT angiography after BNI. Berne et al.59 found CT angiography to have a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 94% when screening patients for blunt cerebrovascular injuries (BCVIs). In contrast, Biffl et al.51 found the sensitivity and specificity for CT angiography to be 68% and 67%, respectively. Further studies are needed directly comparing conventional angiography and CT angiography.

Color Flow Doppler

CFD after BNI may help identify dissections, thrombosis, or pseudoaneurysms of the carotid and vertebral arteries. Its limited visualization of the distal carotid arteries and the portions of the vertebral arteries protected by the cervical spine can be a problem. In a multicenter trial, Cogbill et al.62 demonsrated that duplex was able to identify 86% of injuries.Likewise, both Fry et al.21 and DiPerna et al.63 found that CFD did not miss a substantial carotid injury in patients with BNI. Both these studies, however, consisted of a limited number of patients.

Angiography

In the past, four-vessel angiography was the mainstay of diagnosis of vascular injuries in the neck. The indications remain controversial. Cothren et al.47 recommend four-vessel angiography for all patients with signs or symptoms of cerebrovascular injury on clinical exam as well as high-risk mechanisms and any of the following: severe facial or cervical spine fracture, basilar skull fracture with carotid canal involvement, near-hanging injury with anoxia, and diffuse axonal injury with depressed mental status.

Endoscopy

Endoscopy is useful to evaluate suspected aerodigestive injury after BNI. Though both rigid and flexible endoscopies are options, flexible endoscopy does not require general anesthesia and can be performed while maintaining cervical spine immobilization in a collar. For laryngotracheal injuries, the combination of flexible laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy can be used to rule out an airway injury. Injuries to the pharynx and cervical esophagus may be difficult to visualize due to blood in the pharyngeal space. If the area of interest cannot be visualized clearly or if there is any suspicion of an esophageal injury, the patient should have a contrast swallow.

SPECIFIC NECK INJURIES

Cerebrovascular Injuries

BCVIs were previously thought to be rare. Increased screening has revealed an incidence ranging from 1% to 2% after trauma.47,49,50,56,57 While controversy remains regarding patients at risk, failure to identify and treat these lesions may result in mortality between 25% and 59% of patients.50,51,62,64,65

Clinical Presentation

Many patients die before reaching a hospital or present to the ED in cardiac arrest. Those surviving to reach the hospital may be completely asymptomatic have subtle findings or active arterial hemorrhage, neck hematoma, and hemodynamic instability. Associated injuries may mask BCVI, but they should be suspected in any patient with a suspicious exam (such as the seatbelt sign; Fig. 26.2), concerning mechanism, or neurologic deficits or deterioration not explained by head CT.

FIGURE 26.2. “Seatbelt Sign” after motor vehicle accident.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree