Basic 12-lead electrocardiography

The 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) is a diagnostic test that helps identify pathologic conditions, especially ischemia and acute myocardial infarction (MI). It provides a more complete view of the heart’s electrical activity than a rhythm strip and can be used to assess left ventricular function more effectively. Patients with conditions that affect the heart’s electrical system may also benefit from a 12-lead ECG, including those with:

cardiac arrhythmias

heart chamber enlargement or hypertrophy

digoxin or other drug toxicity

electrolyte imbalances

pulmonary embolism

pericarditis

pacemakers

hypothermia.

Like other diagnostic tests, a 12-lead ECG must be viewed in conjunction with other clinical data. Therefore, always correlate the patient’s ECG results with the history, physical assessment findings, and results of laboratory and other diagnostic studies as well as the drug regimen.

Remember, too, that an ECG can be done in various ways, including over a telephone line. (See Transtelephonic cardiac monitoring, page 246.) In fact, transtelephonic monitoring has become increasingly important as a tool for assessing patients at home and in other nonclinical settings.

Fundamentals

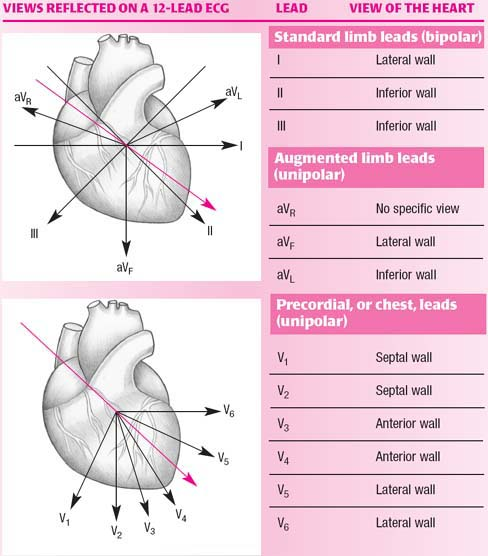

The 12-lead ECG records the heart’s electrical activity using a series of electrodes placed on the patient’s extremities and chest wall. The 12 leads include three bipolar limb leads (I, II, III), three unipolar augmented limb leads (aVR, aVL, and aVF), and six unipolar precordial, or chest,

leads (V1, V2, V3, V4, V5, and V6). These leads provide 12 different views of the heart’s electrical activity. (See ECG leads.)

leads (V1, V2, V3, V4, V5, and V6). These leads provide 12 different views of the heart’s electrical activity. (See ECG leads.)

Transtelephonic cardiac monitoring

Using a special recorder-transmitter, patients at home can transmit electrocardiograms (ECGs) by telephone to a central monitoring center for immediate interpretation. This commonly used technique, called transtelephonic cardiac monitoring (TTM), reduces health care costs.

Nurses play an important role in TTM. Besides performing extensive patient and family teaching, they may operate the central monitoring center and help interpret ECGs sent by patients.

TTM allows a practitioner to assess transient conditions that cause such symptoms as palpitations, dizziness, syncope, confusion, paroxysmal dyspnea, and chest pain. Such conditions, which aren’t commonly apparent while the patient is with a practitioner, can make diagnosis difficult and costly.

With TTM, the patient can transmit an ECG recording from his home when the symptoms appear, avoiding the need to go to the hospital and offering a greater opportunity for early diagnosis. Even if symptoms seldom appear, the patient can keep the equipment for long periods, which further aids in the diagnosis of the patient’s condition.

Home care

TTM can also be used by a patient having cardiac rehabilitation at home. He’ll be called regularly during this period to assess his progress. Because of this continuous monitoring, TTM can help reduce the anxiety felt by the patient and his family after discharge, especially if the patient suffered a myocardial infarction.

TTM is especially valuable for assessing the effects of drugs and for diagnosing and managing paroxysmal arrhythmias. In both cases, TTM can eliminate the need for admitting the patient for evaluation and a potentially lengthy hospital stay.

Understanding TTM equipment

TTM requires three main pieces of equipment: an ECG recorder-transmitter, a standard telephone line, and a receiver. The ECG recorder-transmitter converts electrical activity from the patient’s heart into acoustic waves. Some models contain built-in memory devices that store recordings of cardiac activity for transmission later.

A standard telephone line is used to transmit information. The receiver converts the acoustic waves transmitted over the telephone line into ECG activity, which is then recorded on ECG paper for interpretation and documentation in the patient’s chart. The recorder-transmitter uses two types of electrodes applied to the finger and chest. The electrodes produce ECG tracings similar to those of a standard 12-lead ECG.

Credit card-size recorder

This recorder operates on a battery and is about the size of a credit card. When a patient becomes symptomatic, he holds the back of the card firmly to the center of his chest and pushes the start button. Four electrodes located on the back of the card sense electrical activity and record it. The card can store 30 seconds of activity and can later transmit the recording across phone lines for evaluation.

Scanning up, down, and across, each lead transmits information about a different area of the heart. The waveforms obtained

from each lead vary depending on the lead’s location in relation to the wave of depolarization passing through the myocardium.

from each lead vary depending on the lead’s location in relation to the wave of depolarization passing through the myocardium.

Limb leads

Precordial leads

The six precordial leads provide information on electrical activity in the heart’s horizontal plane, a transverse view through the middle of the heart, dividing it into upper and lower portions. Electrical activity is recorded from either a superior or an inferior approach.

Electrical axis

As well as assessing 12 different leads, a 12-lead ECG records the heart’s electrical axis. The term axis refers to the direction of depolarization as it spreads through the heart. As impulses travel through the heart, they generate small electrical forces called instantaneous vectors. The mean of these vectors represents the force and direction of the wave of depolarization through the heart—the electrical axis. The electrical axis is also called the mean instantaneous vector and the mean QRS vector.

In a healthy heart, impulses originate in the sinoatrial node, travel through the atria to the atrioventricular node, and then to the ventricles. Most of the movement of the impulses is downward and to the left, the direction of a normal axis.

In an unhealthy heart, axis direction varies. That’s because the direction of electrical activity travels away from areas of damage or necrosis and toward areas of hypertrophy. Knowing the normal deflection of each lead will help you evaluate whether the electrical axis is normal or abnormal.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree