Key Concepts

Out of the operating room anesthesia requires the anesthesia provider to work in remote locations in a hospital, where ease of access to the patient and anesthesia equipment is compromised; furthermore, the staff at these locations may be unfamiliar with the requirements for safe anesthetic delivery.

Out of the operating room anesthesia requires the anesthesia provider to work in remote locations in a hospital, where ease of access to the patient and anesthesia equipment is compromised; furthermore, the staff at these locations may be unfamiliar with the requirements for safe anesthetic delivery.

In their guidelines and statements, the American Society of Anesthesiologists reminds anesthesia staff that it is important that both the physical and operational infrastructure is in place at any location to ensure the safe conduct of anesthesia.

In their guidelines and statements, the American Society of Anesthesiologists reminds anesthesia staff that it is important that both the physical and operational infrastructure is in place at any location to ensure the safe conduct of anesthesia.

The underlying reason for ambulatory anesthesia and surgery is that it is less expensive and more convenient for the patient than inpatient admission.

The underlying reason for ambulatory anesthesia and surgery is that it is less expensive and more convenient for the patient than inpatient admission.

Regional and local anesthetic techniques are becoming increasingly popular in managing ambulatory orthopedic surgery.

Regional and local anesthetic techniques are becoming increasingly popular in managing ambulatory orthopedic surgery.

In general, ambulatory surgeries should be of a complexity and duration such that one could reasonably assume that the patient will make an expeditious recovery.

In general, ambulatory surgeries should be of a complexity and duration such that one could reasonably assume that the patient will make an expeditious recovery.

Factors considered in selecting patients for ambulatory procedures include: systemic illnesses and their current management, airway management problems, sleep apnea, morbid obesity, previous adverse anesthesia outcomes (eg, malignant hyperthermia), allergies, and the patient’s social network (eg, availability of someone to be responsive to the patient for 24 h).

Factors considered in selecting patients for ambulatory procedures include: systemic illnesses and their current management, airway management problems, sleep apnea, morbid obesity, previous adverse anesthesia outcomes (eg, malignant hyperthermia), allergies, and the patient’s social network (eg, availability of someone to be responsive to the patient for 24 h).

Ambulatory, Nonoperating Room, & Office-Based Anesthesia: Introduction

Outpatient/ambulatory anesthesia is the subspecialty of anesthesiology that deals with the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative anesthetic care of patients undergoing elective, same-day surgical procedures. Patients undergoing ambulatory surgery rarely require admission to a hospital and are fit enough to be discharged from the surgical facility after the procedure.

Nonoperating room anesthesia (or out of the operating room anesthesia) refers to both inpatients and ambulatory surgery patients who undergo anesthesia in settings outside of a traditional operating room. These patients can vary greatly, ranging from claustrophobic individuals in need of anesthesia for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) procedures to critically ill septic patients undergoing endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in the gastrointestinal suite.  Out of the operating room anesthesia requires the anesthesia provider to work in remote locations in a hospital, where ease of access to the patient and anesthesia equipment is compromised; furthermore, the staff at these locations may be unfamiliar with the requirements for safe anesthetic delivery.

Out of the operating room anesthesia requires the anesthesia provider to work in remote locations in a hospital, where ease of access to the patient and anesthesia equipment is compromised; furthermore, the staff at these locations may be unfamiliar with the requirements for safe anesthetic delivery.

Office-based anesthesia refers to the delivery of anesthesia in a practitioner’s office that has a procedural suite incorporated into its design. Office-based anesthesia is frequently administered to patients undergoing cosmetic surgery, and anesthesia for dental procedures is also routinely performed in an office-based setting.

Although treatment may be similar for inpatients, ambulatory surgery center patients, out of the operating room patients, and office-based anesthesia patients, there are nonetheless various guidelines and statements from the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) that pertain to these different locations. All of these recommendations should be reviewed at the ASA website (www.asahq.org/For-Healthcare-Professionals/Standards-Guidelines-and-Statements.aspx), as they are subject to change and modification.  In their guidelines and statements, the ASA reminds anesthesia staff that it is important that both the physical and operational infrastructure is in place at any location to ensure the safe conduct of anesthesia. In addition to the ASA guidelines, state regulatory guidelines, which include specific requirements for safety, governance, and emergency protocols for both office-based and free-standing ambulatory surgery centers, have also been established. Accreditation agencies, such as the Joint Commission, Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Healthcare, and American Association for the Accreditation of Ambulatory Surgical Facilities, engage in various inspections and reviews to ensure that facilities meet acceptable standards for the procedural services provided. Anesthesia staff should confirm that both the infrastructure and operational policies are consistent with acceptable anesthesia practice standards before providing anesthesia in such settings.

In their guidelines and statements, the ASA reminds anesthesia staff that it is important that both the physical and operational infrastructure is in place at any location to ensure the safe conduct of anesthesia. In addition to the ASA guidelines, state regulatory guidelines, which include specific requirements for safety, governance, and emergency protocols for both office-based and free-standing ambulatory surgery centers, have also been established. Accreditation agencies, such as the Joint Commission, Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Healthcare, and American Association for the Accreditation of Ambulatory Surgical Facilities, engage in various inspections and reviews to ensure that facilities meet acceptable standards for the procedural services provided. Anesthesia staff should confirm that both the infrastructure and operational policies are consistent with acceptable anesthesia practice standards before providing anesthesia in such settings.

Advances in Ambulatory Anesthesia and Surgery

Most patients are no longer admitted prior to the day of elective surgery. The trend for same-day admittance has been facilitated by advancements in surgical technique and technology (eg, laparoscopy), resulting in less invasive surgery, advancements in anesthesia care (eg, shorter acting medications) and improved postoperative pain and nausea management.  The underlying reason for ambulatory anesthesia and surgery is that it is less expensive and more convenient for the patient than inpatient admission. The transition from open cholecystectomy to a laparoscopic approach represents the type of development that permits a shortened postoperative course and ambulatory patient management. Consequently, a common procedure that once required hospital admission is now performed as outpatient surgery.

The underlying reason for ambulatory anesthesia and surgery is that it is less expensive and more convenient for the patient than inpatient admission. The transition from open cholecystectomy to a laparoscopic approach represents the type of development that permits a shortened postoperative course and ambulatory patient management. Consequently, a common procedure that once required hospital admission is now performed as outpatient surgery.

The use of short-acting anesthetic agents (eg, propofol, desflurane, and rocuronium) has likewise contributed to making ambulatory surgery easier; however, such cases were performed successfully using thiopental, isoflurane, and succinylcholine when the newer agents were not available. Although inhalational agents (eg, sevoflurane and desflurane) lead to prompt emergence, they also contribute to postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV). Propofol, which may have antiemetic effects as a part of total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA), can potentially reduce PONV; however, TIVA may require more time for patients to meet discharge criteria.  Regional and local anesthetic techniques are becoming increasingly popular in managing ambulatory orthopedic surgery. The use of ultrasound and nerve stimulation has improved regional block success rates. The use of regional techniques decreases postoperative opioid requirements, potentially reducing the likelihood of PONV. For example, paravertebral blocks are increasingly used to manage office-based breast augmentation surgery. Improved airway management using devices, such as the laryngeal mask airway (LMA) and video laryngoscopy, have likewise contributed to improved patient care. Consequently, anesthesia personnel working as solo providers in an office-based setting are better able to avoid airway catastrophes.

Regional and local anesthetic techniques are becoming increasingly popular in managing ambulatory orthopedic surgery. The use of ultrasound and nerve stimulation has improved regional block success rates. The use of regional techniques decreases postoperative opioid requirements, potentially reducing the likelihood of PONV. For example, paravertebral blocks are increasingly used to manage office-based breast augmentation surgery. Improved airway management using devices, such as the laryngeal mask airway (LMA) and video laryngoscopy, have likewise contributed to improved patient care. Consequently, anesthesia personnel working as solo providers in an office-based setting are better able to avoid airway catastrophes.

Candidates for Ambulatory and Office-Based Anesthesia

With an aging and increasingly obese population, patients with significant comorbidities present for ambulatory surgery. Although age per se is not a factor in determining candidacy for ambulatory procedures, each patient must be considered in the context of his or her comorbidities, the type of surgery to be performed, and the expected response to anesthesia.  In general, ambulatory surgeries should be of a complexity and duration such that one could reasonably assume that the patient will make an expeditious recovery. ASA physical status and a thorough history and physical exam are crucial in the screening of patients selected for ambulatory or office-based surgery. ASA 4 and 5 patients normally would not be candidates for ambulatory surgery, whereas ASA 1 and 2 patients would be prime candidates for such surgery. ASA 3 patients with diabetes, hypertension, and stable coronary artery disease would not be precluded from an ambulatory procedure provided that their diseases are well controlled. Ultimately, the surgeon and anesthesia provider must identify patients for whom an ambulatory or office-based setting is likely to provide benefits (eg, convenience, reduced costs and charges) that outweigh risks (eg, the lack of immediate availability of all hospital services, such as a cardiac catheterization laboratory, emergency cardiovascular stents, assistance with airway rescue, rapid consultation).

In general, ambulatory surgeries should be of a complexity and duration such that one could reasonably assume that the patient will make an expeditious recovery. ASA physical status and a thorough history and physical exam are crucial in the screening of patients selected for ambulatory or office-based surgery. ASA 4 and 5 patients normally would not be candidates for ambulatory surgery, whereas ASA 1 and 2 patients would be prime candidates for such surgery. ASA 3 patients with diabetes, hypertension, and stable coronary artery disease would not be precluded from an ambulatory procedure provided that their diseases are well controlled. Ultimately, the surgeon and anesthesia provider must identify patients for whom an ambulatory or office-based setting is likely to provide benefits (eg, convenience, reduced costs and charges) that outweigh risks (eg, the lack of immediate availability of all hospital services, such as a cardiac catheterization laboratory, emergency cardiovascular stents, assistance with airway rescue, rapid consultation).

Factors considered in selecting patients for ambulatory procedures include: systemic illnesses and their current management, airway management problems, sleep apnea, morbid obesity, previous adverse anesthesia outcomes (eg, malignant hyperthermia), allergies, and the patient’s social network (eg, availability of someone to be responsive to the patient for 24 h).

Factors considered in selecting patients for ambulatory procedures include: systemic illnesses and their current management, airway management problems, sleep apnea, morbid obesity, previous adverse anesthesia outcomes (eg, malignant hyperthermia), allergies, and the patient’s social network (eg, availability of someone to be responsive to the patient for 24 h).

Patients with known or likely difficult airways should probably not be candidates for office-based procedures; however, they may be appropriately cared for in a well equipped and fully staffed ambulatory surgery center. Important considerations for such patients include the availability of difficult airway equipment, such as an intubating LMA or videolaryngoscope, the availability of additional experienced anesthesia providers, and surgeons/anesthesiologists capable of performing emergency tracheostomy/cricothyroidotomy. If there are concerns regarding the ability to manage the airway in an ambulatory surgery setting, or if a surgical airway is thought to be a possibility, the patient may be better served in a hospital setting where immediate consultation and assistance is available.

Similarly, patients with unstable comorbid conditions, such as decompensated congestive heart failure or uncontrolled hypertension, may benefit more from having their procedure performed in a hospital than a free-standing facility. Indeed, many patients undergo ambulatory procedures in a hospital, as opposed to a free-standing surgery center or office. Such patients have the benefit of both the availability of a hospital’s resources and the convenience of being an ambulatory patient. Should their condition warrant additional care, hospital admittance is possible; however, such flexibility comes with the costs associated with hospital care.

The anesthesiologist must know which preexisting medical conditions predict a specific intraoperative and/or postoperative adverse event (AE) for the patient in question. Likewise, procedures suitable for ambulatory surgery should have a minimal risk of perioperative hemorrhage, airway compromise, and no particular requirement for specialized postoperative care. Based on risk identification, the anesthesiologist should be able to mitigate unforeseen AEs and provide optimal care for patients in this type of setting. Although current evidence-based medicine can provide recommendations for some high-risk ambulatory issues, evidence is lacking for most such situations.

Specific Patient Conditions and Ambulatory Surgery

Obesity is associated with many concomitant disease states, such as hypertension, diabetes, hyperlidipemia, and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). The physiologic derangements that accompany these conditions include changes in oxygen demand, carbon dioxide production, alveolar ventilation, and cardiac output. Patients with obesity and OSA are at increased risk of postoperative respiratory complications, such as prolonged airway obstruction and apnea. Scores for predicting the probability of these complications can aid in the preoperative assessment and referral to a hospital setting (Tables 44-1 and 44-2). Although a sleep study is the standard way to diagnose sleep apnea, many patients with OSA have never been identified as having OSA. Consequently, an anesthesiologist may be the first physician to detect the presence or risk of sleep apnea. The ASA has provided suggestions on the types of procedures and anesthetics that can safely be used in ambulatory patients with OSA (Table 44-3). In addition to the usual discharge criteria, the ASA also recommends the following in patients with OSA:

- Return of room air oxygen saturation to baseline level

- No hypoxemic episodes or periods of airway obstruction when left alone

- Monitoring for 3 hours longer prior to discharge than patients without OSA

- Monitoring for 7 hours following an episode of airway obstruction or hypoxemia while breathing room air in an unstimulating environment

| ||

| Severity of OSA | Adult AHI | Pediatric AHI |

| None | 0-5 | 0 |

| Mild OSA | 6-20 | 1-5 |

| Moderate OSA | 21-40 | 6-10 |

| Severe OSA | >40 | >10 |

| Points | |

|---|---|

| A. Severity of sleep apnea based on sleep study (or clinical indicators if sleep study not available). Point score _______ (0-3)1-2 | |

| Severity of OSA (Table 44-1) | |

| None | 0 |

| Mild | 1 |

| Moderate | 2 |

| Severe | 3 |

| B. Invasiveness of surgery and anesthesia. Point score _______ (0-3) | |

| Type of surgery and anesthesia | |

| Superficial surgery under local or peripheral nerve block anesthesia without sedation | 0 |

| Superficial surgery with moderate sedation or general anesthesia | 1 |

| Peripheral surgery with spinal or epidural anesthesia (with no more than moderate sedation) | 1 |

| Peripheral surgery with general anesthesia | 2 |

| Airway surgery with moderate sedation | 2 |

| Major surgery, general anesthesia | 3 |

| Airway surgery, general anesthesia | 3 |

| C. Requirement for postoperative opioids. Point score ________ (0-3) | |

| Opioid requirement | |

| None | 0 |

| Low-dose oral opioids | 1 |

| High-dose oral opioids, parenteral or neuraxial opioids | 3 |

| D. Estimation of perioperative risk. Overall score = the score for A plus the greater of the score for either B or C. Point score _______ (0-6)3 |

| Type of Surgery/Anesthesia | Consultant Opinion |

|---|---|

| Superficial surgery/local or regional anesthesia | Agree |

| Superficial surgery/general anesthesia | Equivocal |

| Airway surgery (adult, e.g., UPPP) | Disagree |

| Tonsillectomy in children less than 3 years old | Disagree |

| Tonsillectomy in children greater than 3 years old | Equivocal |

| Minor orthopedic surgery/local or regional anesthesia | Agree |

| Minor orthopedic surgery/general anesthesia | Equivocal |

| Gynecologic laparoscopy | Equivocal |

| Laparoscopic surgery, upper abdomen | Disagree |

| Lithotripsy | Agree |

| OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; UPPP, uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. | |

According to the ASA Task Force on Obesity and OSA, these OSA patients can be managed safely as outpatients; however, they have an increased risk of postoperative complications requiring increased monitoring, availability of radiologic/laboratory services, and availability of continuous positive airway pressure and mechanical ventilation, thus making an office-based setting potentially inadequate for managing complications that may arise. Nonetheless, under certain conditions, anesthesia and surgery can be performed in an ambulatory surgery center or hospital outpatient facility.

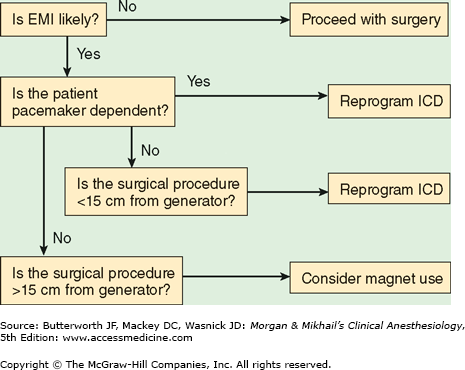

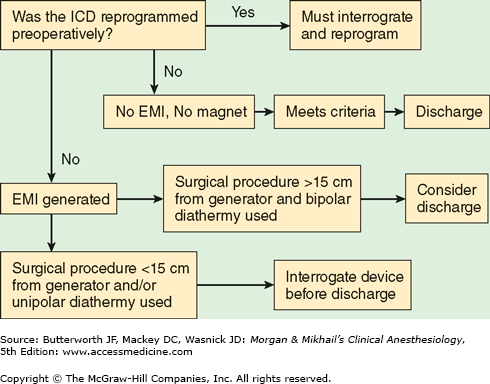

Increasingly, patients present to ambulatory surgery with a variety of cardiac conditions treated both pharmacologically and mechanically (eg, cardiac resynchronization therapy, implantable cardioverter-defibrillators [ICDs], stents). It is therefore likely that anesthesia staff working in ambulatory settings will encounter increasing numbers of such patients, who, despite a cardiac history, have stable cardiac conditions. Patients previously treated with stents are likely to be on antiplatelet regimens. As always, these agents should not be discontinued unless a discussion has occurred between the patient, cardiologist, and surgeon regarding both the necessity of surgery and the discontinuation of antiplatelet therapy. Likewise, β-blockers should be continued perioperatively. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers may contribute to transient hypotension with anesthesia induction, but their continuation or discontinuation perioperatively seems to have minimal effects, as patients so treated likely will need to have intraoperative hypotension corrected in either case. The ASA guidelines recommend that patients presenting with a pacemaker or ICD should not leave a monitored setting until the device is interrogated, if electrocautery was employed; however, this ASA recommendation is controversial, as some argue that if bipolar cautery is used at a distance of greater than 15 cm from the device, immediate interrogation of the device is not necessary prior to discharge from a monitored setting. Likewise, if an ICD is present, and there is anticipated electromagnetic interference the device’s antitachycardia features should be inhibited perioperatively (see Figures 44-1 and 44-2).

Figure 44-1

Preoperative considerations in a patient with an implanted cardioverter defibrillator. EMI, electromagnetic interference; ICD, implanted cardioverter defibrillator. (Reproduced, with permission, from Joshi GP: Perioperative management of outpatients with implantable cardioverter defibrillators. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2009;22:701.)

Figure 44-2

Postoperative considerations in a patient with an implanted cardioverter defibrillator. EMI, electromagnetic interference; ICD, implanted cardioverter defibrillator. (Reproduced, with permission, from Joshi GP: Perioperative management of outpatients with implantable cardioverter defibrillators. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2009;22:701.)

In a consensus statement on perioperative glucose control, the Society for Ambulatory Anesthesia found insufficient evidence to make strong recommendations about glucose management in ambulatory patients, and thus management suggestions parallel those of the inpatient population; however, the panel recommends a target intraoperative blood glucose concentration of <180 mg/dL.