FUNDAMENTAL PRINCIPLES

| ACUTE CARE SURGERY: GENERAL PRINCIPLES |

ACUTE CARE SURGERY-GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Expedient assessment/intervention is the paramount axiom of acute care surgery management. This in no way undermines or devalues the merits of comprehensive assessments. On the contrary, prioritization of management—in an attempt to quickly address disease and injury that can rapidly result in severe morbidity and mortality—has always been the cornerstone of all aspects of medicine. Emergency operative intervention, precluding a comprehensive assessment and preoperative clearance, is indicated in some circumstances. In such case, the complete evaluation is done after stabilization of the patient. While the importance of preoperative clearance cannot be over emphasized, it often cannot (and should not) be implemented in the acute care setting for a risk benefit analysis of delaying surgical intervention would be unfavorable and detrimental to the health status of the patient. However, when appropriate, a systematic approach to preoperative clearance should be done.

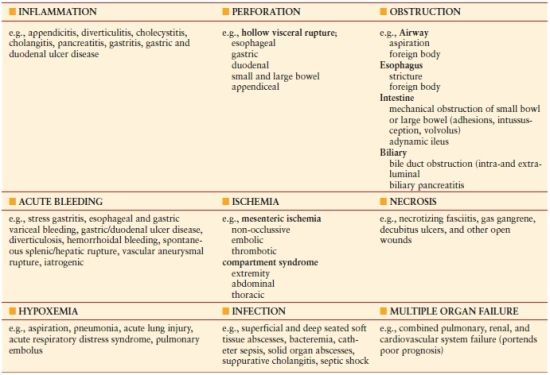

The general principles of acute care surgery, in the nontrauma setting, must be applicable in the following areas of emergency general surgery and surgical critical care: (1) inflammation, (2) perforation, (3) obstruction, (4) bleeding, (5) ischemia, (6) necrosis, (7) hypoxia, and (8) infection.

CORE MANAGEMENT PRINCIPLES

In the nontrauma setting, the core management principles (the four Es) in acute care surgery are the following:

- Expeditious initial assessment

- End point–guided resuscitation

- Early intervention and definitive management (if possible)

- Essential physiologic monitoring

Expeditious Initial Assessment

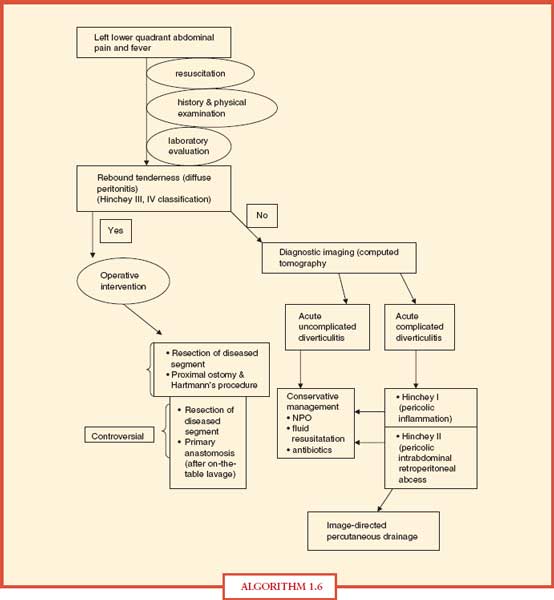

Each of the presentations highlighted in Table 1.1 is time sensitive and, therefore, often necessitates a rapid, methodical, and accurate evaluation process. When applicable, this would entail obtaining a relevant history from the patient and possible family members or health providers caring for the patient. In addition, the patient should, initially, undergo a focused physical examination, which can be expanded to a full and complete exam, if emergency intervention does not preclude such an assessment. Integrated in the assessment and resuscitative phase should be the acquisition of the important laboratory values and any required imaging studies necessary to provide quality surgical care. Because of the broad spectrum of presentations in acute care surgery, there is some variability in the diagnostic/treatment paradigms although the core management principles remain the same. For example, the otherwise healthy young male patient who presents with relatively acute onset of right lower-quadrant pain (preceded by periumbilical pain), anorexia, and a fever is likely to have acute appendicitis. If physical exam confirms right lower-quadrant tenderness with localized peritoneal signs and no other remarkable abnormal findings, the patient should have ongoing resuscitation, antibiotics, and operative intervention for suspected acute appendicitis. While some physicians may advocate obtaining a CT scan, it is not essential in this setting. Also, if a patient presents toxic with diffuse peritonitis and has associated comorbidities suggestive of secondary peritonitis (e.g., perforated duodenal ulcer), he/she should be considered for surgery. Any patient with an acute surgical abdomen should not have intervention delayed by unnecessary imaging studies. However, the elderly patient, who has multiple comorbidities, presenting with an insidious onset of left lower-quadrant pain and tenderness elevated on abdominal palpation in this area will likely have diverticulitis. Radiologic imaging, specifically computed tomography (CT), would be essential in the diagnostic workup, disease classification, and management of this patient. A CT scan that demonstrates a contained pericolonic abscess secondary to a perforated inflamed diverticulum (Hinchey II classification) would dictate the need for CT scan–directed percutaneous drainage of the abscess and nonoperative management.

TABLE 1.1

BROAD SPECTRUM OF ACUTE CARE SURGERY (NONTRAUMA)—EMERGENCY GENERAL SURGERY AND SURGICAL CRITICAL CARE

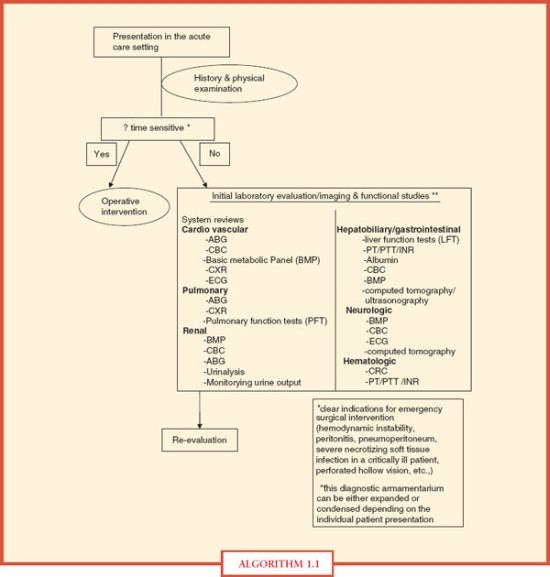

The importance of preoperative laboratory assessment cannot be overstated. Such an evaluation is needed to help determine if there are associated medical conditions that could adversely impact the postoperative course of a patient. However, in the acute care surgical setting, optimal preoperative evaluation, including imaging and laboratory studies, often cannot be accomplished (Algorithm. 1.1).

ALGORITHM 1.1 Preoperative assessment.

End Point–guided Resuscitation

Optimal resuscitation is imperative in the management of any patient in the acute care setting. It is a dynamic process that requires a continued assessment process to ensure that the targeted end points of resuscitation are achieved. The debate continues, however, over the optimal end points of resuscitation in trauma patients. Urine output, lactate levels, base deficit, gastric intramucosal pH, and direct determination of oxygen delivery and consumption are all proposed markers for end points of resuscitation. Irrespective of the end point chosen, the overarching goal in the resuscitation of patients is correction of inadequate organ perfusion and tissue oxygenation. Inability to achieve adequate organ perfusion and tissue oxygenation can result in anaerobic metabolism with the development of acidosis and an associated oxygen debt. Scalea et al. reported that inadequate tissue perfusion can exist even when the conventional end points (e.g., blood pressure, heart rate, and urine output) of resuscitation are normal.1

Early Intervention and Definitive Management, If Possible

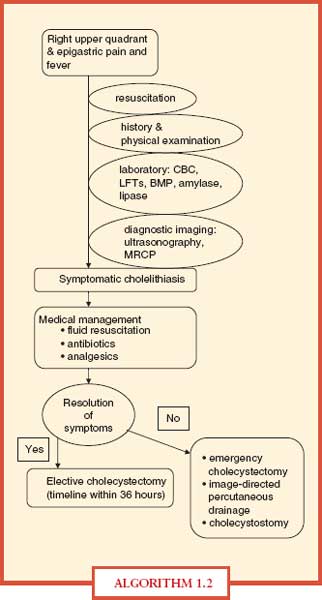

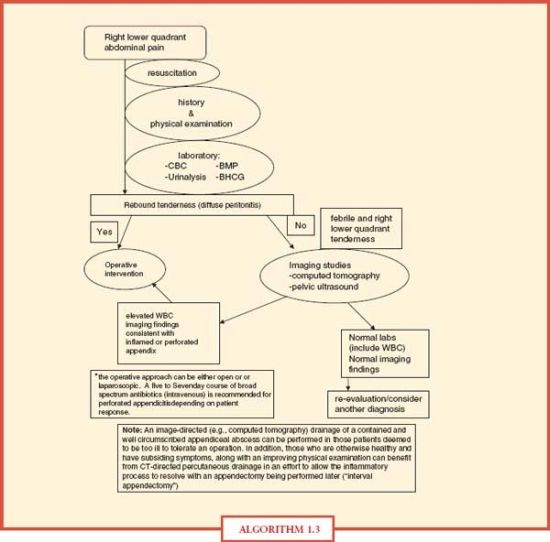

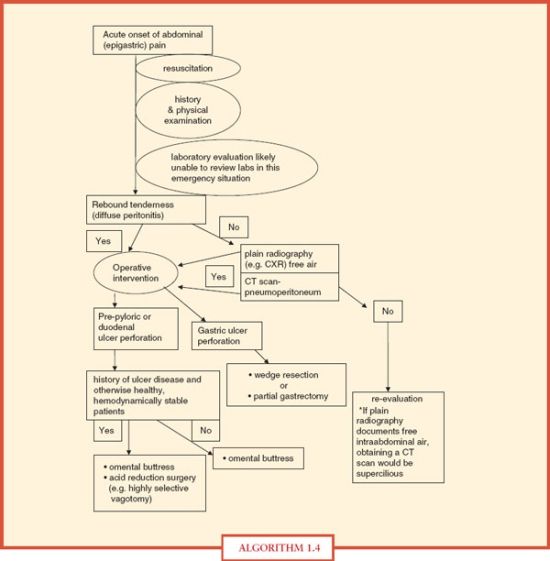

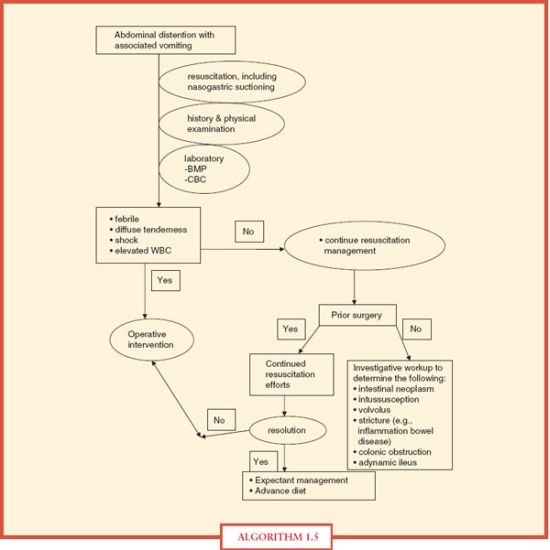

In the acute care setting, irrespective of the specific illness/injury encountered, early and often definitive intervention is the essential component of management. Specific treatment paradigms differ depending on the specific disease entity and its unique presentation (Algorithms. –1.21.6).

ALGORITHM 1.2 Acute cholecystitis.

ALGORITHM 1.3 Appendicitis

ALGORITHM 1.4 Perforated ulcer (duodenal and gastric).

ALGORITHM 1.5 Small bowel obstruction.

ALGORITHM 1.6 Diverticulitis

GENERAL PRINCIPLES—TRAUMA SETTING

Prior to focusing on the specific anatomical region where there is an obvious traumatic injury, an initial assessment of the entire patient is imperative.

The concept of initial assessment includes the following components: (1) rapid primary survey, (2) resuscitation, (3) detailed secondary survey (evaluation), and (4) reevaluation. Such an assessment is the cornerstone of the Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) program. Integrated into primary and secondary surveys are specific adjuncts. Such adjuncts include the application of electrocardiographic monitoring and the utilization of other monitoring modalities such as arterial blood gas determination, pulse oximetry, the measurement of ventilatory rate and blood pressure, insertion of urinary or gastric catheters, and incorporation of necessary x-rays and other diagnostic studies, when applicable, such as focused abdominal sonography for trauma (FAST) exam, other diagnostic studies (plain radiography of the spine/chest/pelvis and CT), and diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL). Determination of the right diagnostic study depends on the mechanism of injury and the hemodynamic status of the patient.

The focus of the primary survey is to both identify and expeditiously address immediate life-threatening injuries. Only after the primary survey is completed (including the initiation of resuscitation) and hemodynamic stability is addressed should the secondary survey be conducted, which entails a head-to-toe (and back to front) physical examination, along with a more detailed history.

PRIMARY SURVEY

Only the emergency care disciplines of medicine have a two-tier approach to their initial assessment of the patient, with primary and secondary surveys as integral components. As highlighted above, the primary survey is designed to quickly detect life-threatening injuries. Therefore, a universal approach has been established with the following prioritization:

- Airway maintenance (with protection of the cervical spine)

- Breathing (ventilation)

- Circulation (including hemorrhage control)

- Disability (neurologic status)

- Exposure/environmental control

Such a systematic and methodical approach (better known as the ABCDEs of the initial assessment) greatly assists the surgical/medical team in the timely management of those injuries that could result in a poor outcome.

A. Airway assessment/management (along with cervical spine protection)

Because loss of a secure airway could be lethal within 4 minutes, airway assessment/management always has the highest priority during the primary survey of the initial assessment of any injured patient, irrespective of the mechanism of injury or the anatomical wound. The chin lift and jaw thrust maneuvers are occasionally helpful in attempting to secure a patient airway. However, in the trauma setting, the airway management of choice is often translaryngeal, endotracheal intubation. If this cannot be achieved due to an upper airway obstruction or some technical difficulty, a surgical airway (needle or surgical cricothyroidotomy) should be the alternative approach. No other management can take precedence over appropriate airway control. Until adequate and sustained oxygenation can be documented, administration of 100% oxygen is required.

B. Breathing (ventilation assessment)

An airway can be adequately established and optimal ventilation still not be achieved. For example, such is the case with an associated tension pneumothorax (other examples include a tension hemothorax, open pneumothorax, or a large flail chest wall segment). Worsening oxygenation and an adverse outcome would ensue unless such problems are expeditiously addressed. Therefore, assessment of breathing is imperative, even when there is an established and secure airway. A patent airway but poor gas exchange will still result in a poor outcome. Tachypnea, absent breath sounds, percussion hyperresonance, distended neck veins, and tracheal deviation are all consistent with inadequate gas exchange. Decompression of the pleural space with a needle/chest tube insertion should be the initial intervention for a pneumo-/hemothorax. A large flail chest, with underlying pulmonary contusion, will likely require endotracheal intubation and positive pressure ventilation.

C. Circulation assessment (adequacy of perfusion management)

The most important initial step in determining adequacy of circulatory perfusion is to quickly identify and control any active source of bleeding, along with restoration of the patient’s blood volume with crystalloid fluid resuscitation and blood products, if required. Decreased levels of consciousness, pale skin color, slow (or nonexistent) capillary refill, cool body temperature, tachycardia, or diminished urinary output are suggestive of inadequate tissue perfusion. Optimal resuscitation requires the insertion of two large-bore intravenous lines and infusion of crystalloid fluids (warmed). Adult patients who are severely compromised will require a fluid bolus (2 L of Ringer’s lactate or saline solution). Children should receive a 20 mL/kg fluid bolus. Blood and blood products are administered as required. Along with the initiation of fluid resuscitation, emphasis needs to remain on identification of the source of active bleeding and stopping the hemorrhage. For a patient in hemorrhagic shock, the source of blood loss will be an open wound with profuse bleeding, or within the thoracic or abdominal cavity, or from an associated pelvic fracture with venous or arterial injuries. Disposition (operating room, angiography suite, etc.) of the patient depends on the site of bleeding. For example, a FAST assessment that documents substantial blood loss in the abdominal cavity in a patient who is hemodynamically labile dictates an emergency celiotomy. However, if the expedited diagnostic workup of a hemodynamically unstable patient who has sustained blunt trauma demonstrates no blood loss in the abdomen or chest, then the source of hemorrhage could be from a pelvic injury that would likely necessitate angiography/embolization if external stabilization (e.g., a commercial wrap or binder) of the pelvic fracture fails to stop the bleeding. Profuse bleeding from open wounds can usually be addressed by application of direct pressure or, occasionally, ligation of torn arteries that can easily be identified and isolated.

D. Disability assessment/management

Only a baseline neurologic examination is required when performing the primary survey to determine neurologic function deterioration that might necessitate surgical intervention. It is inappropriate to attempt a detailed neurologic examination initially. Such a comprehensive examination should be done during the secondary survey. This baseline neurologic assessment could be the determination of the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), with an emphasis on the best motor or verbal response, and eye opening. An alternative approach for a rapid neurologic evaluation would be the assessment of the pupillary size and reaction, along with establishing the patient’s level of consciousness (alert, responds to visual stimuli, responds only to painful stimuli or unresponsive to all stimuli). The caveat that must be highlighted is that neurologic deterioration can occur rapidly and a patient with a devastating injury can have a lucid interval (e.g., epidural hematoma). Because the leading causes of secondary brain injury are hypoxia and hypotension, adequate cerebral oxygenation and perfusion are essential in the management of a patient with neurologic injury.

E. Exposure/environmental control

To perform a thorough examination, the patient must be completely undressed. This often requires cutting off the garments to safely expedite such exposure. However, care must be taken to keep the patient from becoming hypothermic. Adjusting the room temperature and infusing warmed intravenous fluids can help establish an optimal environment for the patient.

The secondary survey should not be started until the primary survey has been completed and resuscitation initiated, with some evidence of normalization of vital signs. It is imperative that this head-to-toe evaluation be performed in a detailed manner to detect less obvious or occult injuries. This is particularly important in the unevaluable (e.g., head injury or severely intoxicated) patient. The physical examination should include a detailed assessment of every anatomical region, including the following:

- Head

- Maxillofacial

- Neck (including cervical spine)

- Chest

- Abdomen

- Perineum (including the rectum and genital organs)

- Back (including the remaining spinal column)

- Extremities (musculoskeletal)

A full neurologic examination needs to be performed, along with an estimate of the GCS score if one was not done during the primary survey. The secondary survey and the utilization (when applicable) of the diagnostic adjuncts previously mentioned will allow detection of more occult or subtle injuries that could, if not found, produce significant morbidity and mortality. When possible, the secondary survey should include a history of the mechanism of injury, along with vital information regarding allergies, medications, past illnesses, recent food intake, and pertinent events related to the injury.

It cannot be overemphasized that frequent reevaluation of the injured patient is critical to detect any deterioration in the patient status. This sometimes requires repeating both the primary and secondary surveys.

TOPOGRAPHY AND CLINICAL ANATOMY

The abdomen is often defined as a component of the torso that has as its superior boundary the left and right hemidiaphragm, which can ascend to the level of the nipples (4th intercostal space) on the frontal aspect and to the tip of the scapula in the back. The inferior boundary of the abdomen is the pelvic floor. For clinical purposes, it is helpful to further divide the abdomen into four areas: (1) anterior abdomen (below the anterior costal margins to above the inguinal ligaments and anterior to the anterior axillary lines), (2) intrathoracic abdomen (from the nipple or the tips of the scapula to the inferior costal margins), (3) flank (inferior scapular tip to the iliac crest and between the posterior and anterior axillary lines), and (4) back (below the tips of the scapula to the iliac crest and between the posterior axillary lines). The majority of the digestive system and urinary tract, along with a substantial network of vasculature and nerves, are contained with the abdominal cavity. A viscera-rich region, the abdomen can often be the harbinger for occult injuries as a result of penetrating wounds, particularly in the unevaluable abdomen as the result of a patient’s compromised sensorium.

Mechanism of Injury—Penetrating Trauma

In addition to the hemodynamic status of the patient, important variables in the decision making in the management of penetrating abdominal injuries are both the mechanism and location of injury (see “Physical Examination”). The kinetic energy generated by hand-driven weapons, such as knives and sharp objects, is substantially less than caused by firearms. Although not always evident, it is important to know the length and width of the wound along with the depth of penetration of the weapon or device that caused the stab injury. For example, a stab injury usually results in a long, more shallow wound that does not penetrate the peritoneum. Local wound management is the primary focus for these injuries with no concern for any potential intra-abdominal injury.2 Although there are some stab wounds that do not penetrate the peritoneal cavity, such cannot just be assumed without some formal determination or serial abdominal examinations to assess for worsening abdominal tenderness or the development of peritoneal signs.

There is notable variability among the full spectrum of firearms in the civilian setting, with this arsenal including handguns, rifles, shotguns, and airguns. The kinetic energy, which correlates with the wounding potential, is dependant on mass and velocity (KE = 1/2 mv2). Therefore, the higher the velocity (v), the greater the wounding potential.3 Because the barrel is longer in a rifle than a handgun, the bullet has more time to accelerate, generating a much higher velocity. A high-velocity missile is propelled at 2,500-5,000 ft per second. Airguns usually fire pellets (e.g., BBs) and are associated with a lower velocity and wounding potential. Shotguns fire a cluster of metal pellets, called a shot. The pellets separate after leaving the barrel, with a rapidly decreasing velocity. At a distance, the wounding potential is diminished. However, at close range (<15 ft), because of the increase in aggregate mass, the tissue destruction is similar to a high-velocity missile injury.

Although each injury should be handled on an individual basis, there are general principles that will provide some guidance in the management of penetrating injuries based on mechanism of injury. With respect to stab wounds, approximately one-third of the wounds do not penetrate the peritoneum and only half of those that penetrate require operative intervention. The number of organs injured and the intra-abdominal sepsis complication rate are significantly less than wounds caused by gunshots.4,5

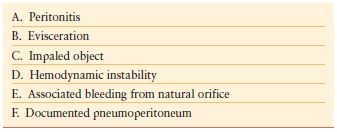

A complete and thorough physical examination of the entire body is essential in the management of penetrating abdominal injury. There are some findings (Table 1.2) on physical examination that are absolute indications for operative intervention. The components of the physical exam should include careful inspection, palpation, and auscultation.

TABLE 1.2

ABSOLUTE INDICATIONS FOR EXPLORATORY LAPAROTOMY IN PENETRATING ABDOMINAL INJURIES

In addition to determination of the location, extent, and the number of wounds, inspection can sometimes determine the trajectory of the missile or other wounding agent and, consequently, guide management decisions. For example, a patient with a documented, superficial tangential gunshot wound (low-velocity), with no other remarkable physical findings, would likely be managed expectantly (observation). However, if a penetrating abdominal injury results in a patient presenting with an evisceration, exploratory laparotomy would be the management option of choice. Palpation will enable the examiner to elicit abdominal tenderness or frank peritoneal signs, along with detection of abdominal distention and rigidity. On occasion, missiles can be palpated lodged in the soft tissue. Unless in a controlled and sterile setting such as the operative theater, probing of a wound should be avoided. Auscultation is also an important component of the physical examination. It can detect diminished or absent bowel sounds that could be suggestive of evolving peritonitis. Also, auscultation could detect a trauma-induced bruit, suggestive of a vascular injury. The examiner must be keenly aware that there are situations in which the abdominal exam will be unreliable due to possible spinal cord injury or a patient’s altered mental state.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Even with penetrating injuries, the abdomen is notorious for hiding its secrets—occult injuries. Access to an extensive diagnostic armamentarium is imperative in the optimal management of these injuries. Strongly advocated by some for abdominal stab wounds, local wound exploration has the advantage of allowing the patient to be discharged from the trauma bay or emergency department, if surgical exploration of the wound fails to demonstrate penetration of the posterior fascia and peritoneum. However, if the patient goes to the operating room for other injuries, the local wound exploration should be done in the surgical suite with better lighting and a more sterile environment. A positive finding during local wound exploration dictates a formal laparotomy or laparoscopy. However, even with local wound exploration as a guide, the nontherapeutic laparotomy rate can be high, given that only a third of the patients with stab wounds to the anterior abdomen require therapeutic laparotomy.6,7 In the patient who has an evaluable abdomen, serial abdominal examinations would be an acceptable alterative to local wound exploration, to determine the need for operative intervention (selective management). Local would exploration should only be done for stab wounds to the anterior abdomen. Such an approach is potentially too hazardous for thoracoabdominal penetrating injuries and back/flank wounds. Plain radiography (abdomen/pelvis/chest) can be pivotal in documenting the presence of missiles and other foreign bodies and determining the trajectory of the injury tract, particularly for wounds from firearms. Also, the presence of free air might be confirmed by plain radiography. Unless there is concern about a retained broken blade, there is little utility for plain radiography for stab injuries.8 The DPL developed by David Root, in 1965, was a major advance in the care of the hemodynamically labile patient who sustained blunt trauma.9 With the advent of FAST and rapid CT, DPL has limited utility. DPL has never had a broad appeal in the diagnostic evaluation of penetrating abdominal wounds. Although some have advocated its use with tangential wounds of the abdominal wall, the technique has failed to receive widespread support.10 Its reliability in detecting clinically important injuries sustained as a result of penetrating abdominal injuries has been a prevailing concern.–1113 The reported sensitivity and specificity of DPL for abdominal stab wounds are 59%-96% and 78%-98%, respectively.14 Also, DPL is a poor diagnostic modality for detection of diaphragmatic and retroperitoneal injuries.

Diagnostic imaging has had the greatest impact in changing the face of trauma management with CT taking the lead in this area. Its ubiquitous presence in the management of blunt abdominal trauma is well established. However, it is becoming an important diagnostic study in the evaluation of penetrating abdominal injuries. In addition to its excellent sensitivity in detection of pneumoperitoneum, free fluid, and abdominal wall/peritoneal penetration, CT is helpful in identifying the tract of the penetrating agent. Hauser et al. recommended the use of “triple contrast” CT in the assessment of penetrating back and flank injuries.15 CT scan evaluation is an essential diagnostic tool in the increasing advocacy for selective management of abdominal gunshot wounds, obviating the need for mandatory surgical exploration.16 However, there still remain two major limitations of CT: detection of intestinal perforation and diaphragmatic injury.

Unless the injury is confined to the solid organ of the abdomen, such as the liver or spleen, the matrix of intestinal gas patterns makes detection of penetrating injuries difficult. Kristensen et al.17 were one of the first teams to introduce the role of ultrasonic scanning as part of the diagnostic armamentarium in trauma management. Kimura and Otsuka18 endorsed using ultrasonography in the emergency room for evaluation of hemoperitoneum. FAST does not have the same broad application in the evaluation of penetrating trauma as it does in blunt trauma assessment. Rozycki et al.19 reported on the expanded role of ultrasonography as the “primary adjuvant modality” for the injured patient assessment. Rozycki also reported that FAST examination was the most accurate for detecting fluid within the pericardial sac. Such a finding would be confirmatory for a cardiac injury and possible cardiac tamponade, given a mechanism of injury that could result in an injury to the heart.

As a diagnostic modality, laparoscopy is not a new innovation. Other specialists have been utilizing this operative intervention for several decades. However, it was formally introduced as a possible diagnostic procedure of choice for specific torso wounds when Ivatury et al.20 critically evaluated laparoscopy in penetrating abdominal trauma. Fabian et al.21 also reported on the efficacy of diagnostic laparoscopy in a prospective analysis.

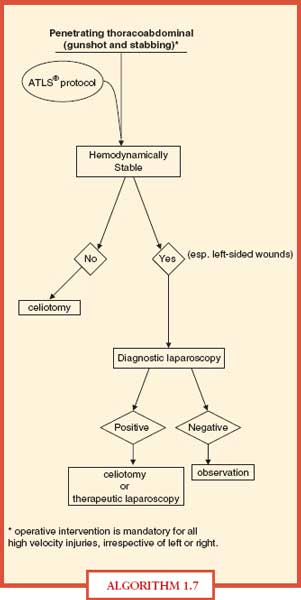

With no conventional diagnostic tool that can conclusively rule out a diaphragmatic laceration or rent, diagnostic laparoscopy becomes the study of choice for penetrating thoracoabdominal injuries, particularly left thoracoabdominal wounds (Algorithm. 1.7). Laparoscopy can also be used to determine peritoneal entry from a tangential penetrating injury.

ALGORITHM 1.7 Management algorithm for penetrating thoracoabdominal injury.

Penetrating Abdominal Injuries and the Hemodynamically Stable and Unstable Patient

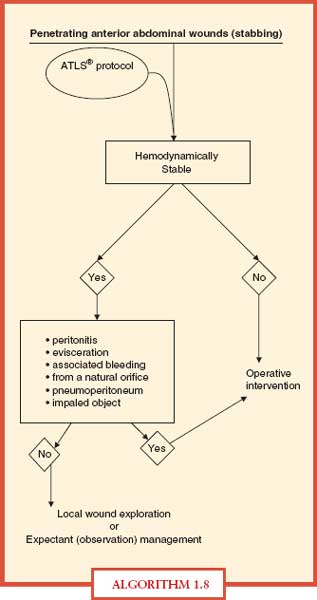

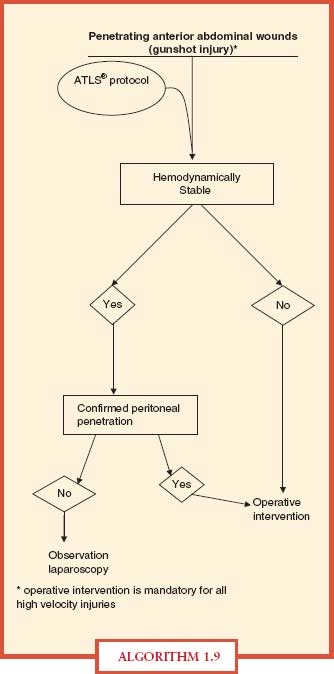

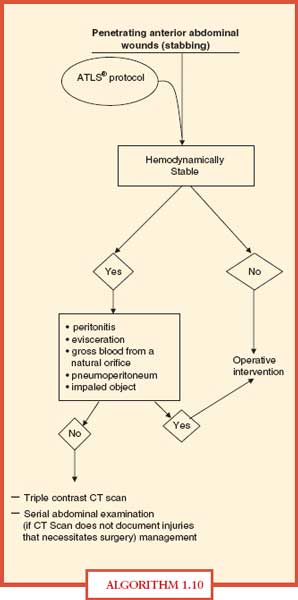

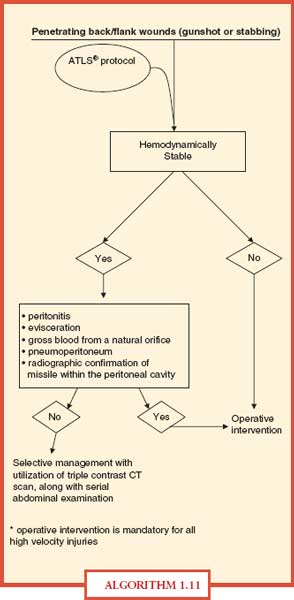

As highlighted above, the management principles in patients who sustain penetrating abdominal injuries and remain hemodynamically stable depend on the mechanism and location of injury, along with the hemodynamic status of the patient. Irrespective of the patient’s hemodynamic parameter, the Adult Trauma Life Support (ATLS) protocol should be strictly followed upon arrival of the patient to the trauma bay (Algorithms. –1.81.11).

ALGORITHM 1.8 Management algorithm for penetrating anterior abdominal injuries.

ALGORITHM 1.9 Management algorithm for penetrating abdominal injuries.

ALGORITHM 1.10 Management algorithm for penetrating abdominal injuries.

ALGORITHM 1.11 Management algorithm for penetrating back/flank injury.

Trauma Laparotomy The operative theater should be large enough to accommodate more than one surgical team, in the event the patient requires simultaneous procedures to be performed. In addition, the room should have the capability of maintaining room temperature as high as the lower 80’s °F to avoid hypothermia. Also, a rapid transfusion device should be in the room to facilitate the delivery of large fluid volume and ensure that the fluid administration is appropriately warm.

Abdominal exploration for trauma has basically four imperatives: (1) hemorrhage control, (2) contamination control, (3) identification of the specific injury (ies), and (4) repair/reconstruction. The abdomen is prepared with a topical antimicrobial from sternal notch to bilateral midthighs and extending the prep laterally to the side of the operating room table followed by widely draping the patient. Such preparation allows expeditious entry into the thorax if needed and possible vascular access or harvesting. Exploration is initiated with a midline vertical incision that should extend from the xiphoid to the symphysis pubis to achieve optimal exposure.

The first priority upon entering the abdomen is control of exsanguinating hemorrhage. Such control can usually be achieved by direct control of the lacerated site or obtaining proximal vascular control. After major hemorrhage is controlled, blood and blood clots are removed. Abdominal packs (radiologically labeled) are used to tamponade any bleeding and allow identification of any injury bleeding. The preferred approach to packing is to divide the falciform ligament and retract the anterior abdominal wall. This will allow manual placement of the packs above the liver. Abdominal packs should also be placed below the liver. This arrangement of the packs on the liver creates a compressive tamponade effect. After manually eviscerating the small bowel out of the cavity, packs should be placed on the remaining three quadrants, with care taken to avoid iatrogenic injury to the spleen. During the packing phase after ongoing hemorrhage has been controlled, the surgeon should communicate with the anesthesia team that major hemorrhage has been controlled and that this would be an optimal time to establish a resuscitative advantage with fluid/blood/blood product administration.

The next priority is control or containment of gross contamination. This begins with the removal of the packs from each quadrant—one quadrant at a time. Packs should be removed from the quadrants that you least suspect to be the source for blood loss, followed by removal of the packs from the final quadrant; the one that you believe is the area of concern.

After control of major hemorrhage has been achieved, any evidence of gross contamination must be addressed immediately. Obvious leakage from intestinal injury can be initially controlled with clamps (e.g., Babcock clamp), staples, or sutures. The entire abdominal gastrointestinal tract needs to be inspected, including the mesenteric and antimesenteric border of the small and large bowel, along with the entire mesentery. Rents in the diaphragm should also be closed to prevent contamination of the thoracic cavity.

Further identification of all intra-abdominal injuries should be initiated. Depending on the mechanism of injury and the estimated trajectory of wounding agent, a thorough and meticulous abdominal exploration should be performed, including exploring the lesser sac to inspect the pancreas and the associated vasculature. In addition, mobilization of the C-loop of the duodenum (Kocher maneuver) might be required, along with medical rotation of the left or right colon for exposure of vital retroperitoneal structures.

The final component of a trauma laparotomy is definitive repair, if possible, of specific injuries. As will be highlighted later in the chapter, the status of the patient dictates whether each of the components of a trauma laparotomy can be achieved at the index operation. A staged celiotomy (“damage control” laparotomy) might be necessary if the patient becomes acidotic, hypothermic, coaglopathic, or hemodynamically compromised.

GENERAL PRINCIPLES IN MANAGEMENT OF SPECIFIC INJURIES

Small Intestine

Isolated small bowel enterotomies can be closed primarily with nonabsorbable sutures for a one-layer closure. If the edges of the enterotomy appear nonviable, they should be gently debrided prior to primary closure. However, multiple contiguous small bowel holes or an intestinal injury on the mesenteric border with associate mesenteric hematoma will likely necessitate segmental resection and anastomosis of the remaining viable segments of the small bowel. The operative goal is always the reestablishment of intestinal continuity without substantial narrowing of the intestinal lumen, along with closure of any associated mesenteric defect. Application of noncrushing bowel claps can contain ongoing contamination while the repair is being performed. Although a hand-sewn or stapler-assisted anastomosis is operator dependant, trauma laparotomies are time-sensitive interventions and expeditious management is imperative.

Colon

The segment of injured bowel should be thoroughly inspected, particularly missile injuries that are most common, through and through enterotomies. This requires adequate mobilization of the colon to visualize the entire circumference of the bowel wall. Initially controversial, an enterotomy (right- or left-sided injuries) of the colon can be closed primarily, irrespective of contamination or transient shock state.22 If the colon injury is so extensive that primary repair is not possible or would severely compromise the lumen, a segmental resection should be performed. Depending on the environmental setting, the remaining proximal segment can be anastomosed to the distal segment or a proximal ostomy and Hartmann’s procedure can be performed. If the distal segment is long enough, a mucous fistula should be established. Documented rectal injuries, below the peritoneal reflection, should necessitate a diverting colostomy and presacral drainage (exiting from the perineum). Such drainage is, however, not universally endorsed.

Stomach/Duodenum

With respect to penetrating wounds of the stomach, the anterior and posterior aspects of the stomach need to be meticulously inspected for accompanying through-and-through injuries. Penetrating injuries of the stomach should be repaired primarily after debridement of nonviable edged. The primary repair can either be single layer with nonabsorbable suture or double layer closure with an absorbable suture (e.g., Vicryl) for the first layer and the second layer closed with nonabsorbable sutures (e.g., silk) Few penetrating injuries of the stomach or primary repairs of a through-and-through gastric injury would compromise the gastric lumen. Duodenal injuries can be repaired primarily in a one- or two-layered fashion if the penetration is less than half the circumference of the duodenum. However, for more complex duodenal injuries, an operative procedure is needed to divert gastric contents away from the injury site (where closure of the wound has been attempted). Pyloric exclusion with the establishment of a gastrojejunostomy is such a procedure.–2325

Pancreas

Superficial or tangential penetrating wounds of the pancreas, without injury to the main pancreatic duct, can be externally drained. However, a penetrating injury that transects the pancreas, including the main pancreatic duct, requires extirpation of the distal pancreas (distal pancreatectomy), particularly if the transection site is to the left of the superior mesenteric vessels. A more proximal penetrating pancreatic injury can generally be managed by wide drainage. If a proximal injury involves the main pancreatic duct, with associated complex duodenal injury (e.g., injury to the ampulla), pancreatoduodenectomy may be necessary. Thus, the indication for pancreatoduodenectomy is combined destructive injury to both the duodenum and pancreas; the operation in essence completes the procedure that the injury has functionally necessitated. Unfortunately, because of the rich vascular network surrounding the pancreas, penetrating pancreatic wounds can be lethal injuries.

Spleen

Most penetrating splenic injuries, particularly gunshot wounds, require splenectomy. To visualize the entire spleen, it should be mobilized to the midline by division of its ligamentous attachments. Superficial penetrating injuries of the spleen can sometimes be managed by either splenorrhaphy or application of a topical hemostatic agent. Splenorrhaphy can be by pledgeted repair or an omental buttress. However, complex repair of the spleen is not a prudent approach in the always time-sensitive trauma setting.

Gallbladder and Liver

Penetrating injuries to the gallbladder dictate the need for extirpation. There is no role for primary repair of a penetrating wound to the gallbladder.

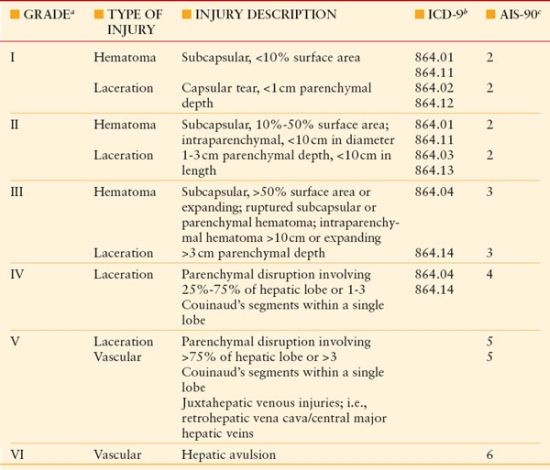

Liver injuries are common in both blunt and penetrating trauma. The majority of injuries are superficial or minor and require no surgical repair. Simple application of pressure or a hemostatic agent or fibrin glue will constitute definitive management of the majority of these injuries. The argon beam coagulation, also a helpful adjunct, in superficial hepatic injuries with persistent oozing generates ionizing energy through an argon gas stream that causes rapid coagulation. The operative armamentarium for complex penetrating hepatic injuries is highlighted in Table 1.3.

TABLE 1.3

LIVER INJURY SCALE OF THE AAST

a Advance one grade for multiple injuries, up to grade III.

b ICD, International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision.

c AIS, Abbreviated Injury Score.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree