ACUTE CARE SURGERY, ETHICS, AND THE LAW

The words moral , ethical , virtuous , and righteous are often used interchangeably to imply actions that are carried out “in accordance with principles or rules of right or good conduct.”1 Morality refers to personal behavior, especially in the sexual domain. Ethical behavior implies conformity with idealized standards of right and wrong, especially within medicine and the law. Virtuous behavior implies moral excellence or, more narrowly, chastity. Righteous behavior indicates freedom from guilt, such that outrage might be the justifiable response to an accusation of bad behavior. A more refined definition of ethical behavior was provided by Mark Twain:

“The fact that man knows right from wrong proves his intellectual superiority to other creatures; but the fact that that he can do wrong proves his moral inferiority to any creature that cannot.”1

Ethical behavior is not absolute but depends upon one’s rearing, education, religion, and socialization. Each culture develops its own ethic. Sanctioned behavior in an insular, parochial environment may be unacceptable in an open, cosmopolitan setting, and vice versa. This reflects the intricate balance between societal and individual rights. The United States has an open society that emphasizes individual rights, but the balance between social and individual rights permeates the legal and medical professions. In clinical medicine, an acute care encounter may challenge the caregiver’s interpretation of established ethical premises; advanced technology may complicate ethical decision making even further (e.g., end-of-life care planning) as implied by General of the Army Omar Bradley: “The world has achieved brilliance without conscience. Ours is a world of nuclear giants and ethical infants.”1 The combination of advanced technology, the interrelationship of medicine and social activism, and increased medical knowledge and awareness of the civil rights of patients has stimulated interest in medical ethics, and particularly surgical ethics, where physical actions that may constitute battery outside of clinical medicine are part of every discussion between surgeon and patient.2

ETHICS AND THE LAW

The legal system defines how disparate members of society can interact and function in a mutually beneficial manner.3 Acts prohibited by law are clearly unethical medically, but legal doctrine is not immutable, nor is it enforced consistently. An example of such inconsistency is the historical debate regarding assisted suicide. A prominent proponent, Doctor Jack Kevorkian, believed that sane patients have a right to die when the pain of a permanent physical illness outweighed the pleasures of living.4 He promulgated his views within the State of Michigan in an unsuccessful attempt to change the state law against assisted suicide, but the several suicides he facilitated created discomfiture for officials reluctant to stake their political reputations on a criminal prosecution that would be deeply unpopular with the electorate, most of whom believed Kevorkian was providing ethical treatment to his patients (opponents opined that only God can terminate a human life). Only after Kevorkian defied the law openly by filming an assisted suicide and making the film public was he charged criminally. A sympathetic jury nonetheless found him guilty. After imprisonment for several years, he was paroled after promising not to be involved further in any assisted suicides. Subsequently, the State of Oregon legalized assisted suicide under specific conditions; this process has been upheld by the United States Supreme Court.5

The Kevorkian saga is but one of many examples of how conflict between personal medical ethics and legal doctrine can eventually lead to changes in the law. Another example of such conflict is the ongoing debate regarding abortion. Ethical and moral beliefs are widely divergent; should abortions be prohibited under any circumstance, or can they be performed in the first trimester when the mother’s life is threatened or when the pregnancy resulted from rape, or is abortion permitted at any time including so-called “partial birth” abortions, whereby the fetus is destroyed prior to delivery and ligation of the umbilical cord?6 Legal definitions regarding the propriety of abortion at different stages of pregnancy are still being tested in the courts. Individual physicians likely will act according to his or her beliefs, but certainly within the law. Although the law may not prohibit actions that many physicians would consider unethical, illegal activity should be deemed unethical regardless. Recognizing the great diversity of views present in society when human individual rights and expectations tend to outweigh societal constraints, this treatise highlights ethical surgical practice, especially as it relates to acute surgical care.

THE SURGEON AND MEDICAL ETHICS

The foundation for ethical surgical practice begins with familial encounters with parents, siblings, and neighbors. Personal relationships are formed with individuals from different backgrounds during early education, and the individual is introduced to the concept of the golden rule , that one should “do unto others as they would do unto you.” Ethical development continues during high school and college, and especially during medical school, when exposure to physicians and patients identifies potential conflicts between personal ethics and the needs of patients. Formal teaching of surgical ethics is now incorporated into postgraduate medical education (i.e., residency training).

SURGICAL CURRICULUM IN ETHICS

Miles Little classified ethical issues as they relate to (1) rescue; (2) proximity; (3) ordeal; (4) aftermath; and (5) presence.7 Little points out that the patient recognizes and is subject to the surgeon’s power during the first encounter, especially so under emergency conditions. However, the recognition of surgical power is contingent on a perception of trust that the surgeon will act in the best interest of the patient, including obtaining appropriate help, to correct the problem (i.e., to rescue the patient). The surgeon’s obligation is inviolate, requiring all that is legally and ethically possible to do be done. The principle of proximity acknowledges that the surgeon will be within the patient’s body, thus the patient must trust that his or her body and mind will be treated with respect. This is particularly relevant when the physical problem cannot be corrected and the surgeon distances him-or herself from the patient as part of instinctual self-preservation. The principle of proximity dictates that the surgeon must share in this failure to heal while continuing to support the patient emotionally. The principle of ordeal recognizes that surgical remediation is associated with pain, discomfort, and inconvenience; however, the patient trusts that suffering will be minimized by the surgeon’s concern for the overall well-being of the patient. The surgeon must strive for optimal patient care by balancing the alleviation of pain and suffering and the avoidance of treatment-related morbidity, especially when the patient requires ongoing treatment. An even greater ethical commitment is required of the surgeon when the emergency is caused by a neoplasm to which the patient will succumb eventually. The fourth principle, aftermath , refers to the need for the surgeon to maximize the patient’s enjoyment of life to the fullest extent subsequent to the acute encounter. The surgeon must recognize the importance of frequent, regular visits as part of the treatment program. The fifth principle emphasized by Little is presence , which refers to the knowledge that the surgeon will always be available to answer questions, alleviate pain, and provide counsel well after the encounter has been completed.7

THE UNPLANNED ENCOUNTER

Occasionally, the surgeon will be in close proximity to an emergency event because of happenstance. For example, the surgeon’s private life might be disrupted by a nearby restaurant patron who suddenly develops tracheal occlusion, the airplane passenger who develops acute respiratory distress, or a driver on the highway who loses control and crashes. It is easy to be passive and conceal one’s surgical skills, but although the surgeon who intervenes on behalf of the endangered citizen enjoys legal protection from “Good Samaritan” laws in all 50 states, there is little statutory requirement for the surgeon to surrender anonymity while acknowledging his or her skills and providing care.8–10 The only exception to this lack of a statutory mandate comes from the State of Vermont, which identifies that the physician in this setting has a “duty to rescue.”11 The Vermont statute states that

“a person who knows that another is exposed to grave physical harm shall, to the extent that the same cannot be rendered without danger or peril to himself or without interference with important duties owed to others, give reasonable assistance to the exposed person unless that assistance or care is being provided by others.”3,11

Although the decision to come to a patient’s rescue in an unplanned encounter is not mandated in most states, it would certainly be considered proper ethical behavior. This code of ethics should stimulate the surgeon to offer assistance at the scene of a motor vehicle collision, to a pedestrian “found down,” and intraoperatively to a fellow surgeon in time of need.

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) has developed a program for teaching ethics to surgical residents.12,13 This program covers: (1) conflict of interest; (2) problems of litigation; (3) substituted decision making; (4) truth in communication; (5) end-of-life decisions; and (6) confidentiality. The practicing surgeon has to adhere to the tenets of each of the above in practicing in an ethical manner.

ADVANCE DIRECTIVES

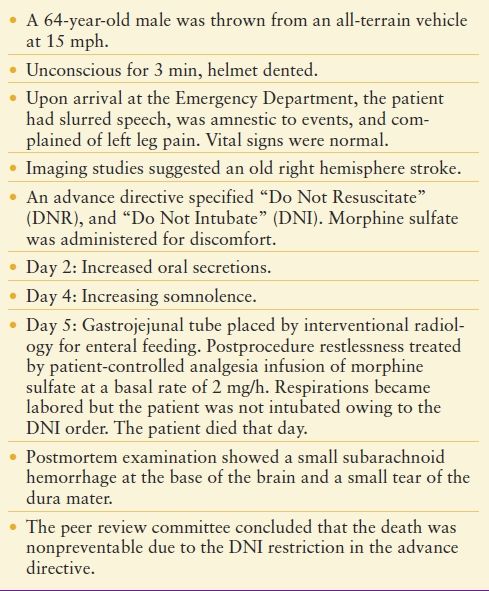

The federal Self Determination Act of 1991 allows a citizen to define a preferred level of care that is to be provided at a future time when the said individual is unable to provide consent at the time of the encounter.2 This act promotes advance directives as a means of controlling one’s destiny even when incapacitated. Despite this option, the vast majority of people do not avail themselves of the benefit.14 Advance directives may be part of a “living will” or may be delegated to an agent who holds the patient’s Durable Power of Attorney for Health Care, also called a health care proxy. Technically, a living will addresses the implementation of care to the terminally ill patient. A decision to not provide care even though death would be imminent without care is best made in consultation by two physicians. The health care proxy transfers legal decision-making authority to an agent empowered to act when an individual lacks capacity to make health care decisions. When such documents have not been executed, decision making accrues to the relative of highest standing, usually the spouse. In cases of dispute, an opinion may be sought from the facility’s legal counsel. Decisions made by surrogates are more easily supported when informed by the patient’s known wishes, but sometimes only a best guess can be made as to what the surrogate believes the patient would want. Sulmasy and Terry15 reported that judgments made by surrogates often do not represent the patient’s best interests, particularly when dealing with terminal illness (i.e., there can be a powerful inclination to do “everything” to the point of futility). This dilemma is compounded when no surrogate decision maker can be identified.16 The surgeon has the ethical responsibility to act in the best interest of the patient, based upon education and experience.16 The golden rule that applies is that the surgeon will probably make a proper decision if the decision is to do what would be preferred for his or her own care in the same circumstance.17 Many such decisions in acute care surgery involve endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation, use of catecholamines to support blood pressure, and pain management. When addressing limits to care stipulated by an advance directive or the patient’s agent, the delivery of care must be modified (Table 62.1).17 This is an example of a preventable death and unethical care in the view of the writers, but the case record provided is incomplete with respect to determination of the patient’s capacity to make decisions and the involvement of a surrogate, therefore many medical ethicists might disagree. In the authors’ view, decisions regarding pain management with opioids must be made in the context of the do not resuscitate (DNR) and do not intubate (DNI) orders. The surgeon is obligated to balance sedation and analgesia in the context of the DNI directive. Ideally, the discussion regarding the limits of care under the DNR order should occur as soon as practicable after admission, and the results made known to all caregivers. For example, it may be decided to adhere strictly to the advance directive (in which case care in the intensive care unit (ICU) may be unjustifiable). Alternatively, some or all aspects of care may be deemed permissible by mutual agreement, or the DNR/DNI orders may be rescinded for a period of time certain (e.g., the periprocedural period or the length of stay in the ICU. Such a discussion is decidedly less than ideal after (or during) a destabilization complication. Absent the discussion, should the patient be intubated until the opioid effects have worn off or been reversed? The authors would opine in the affirmative, after which further discussion with patient and family would determine subsequent care, because most advance directives are designed to prevent futile care or prolonged terminal care, not the short-term management of a reversible complication, but not all medical ethicists would agree.17,18

TABLE 62.1

EXAMPLE CASE OF HEALTH CARE LIMITED BY ADVANCE DIRECTIVE

Providing optimal care in an ethical manner is more complicated when dealing with the incapacitated patient.18 Legally, one must obtain informed consent.17 The State of New York defines “lack of informed consent” to mean:

“the failure of a person providing the professional treatment or diagnosis to disclose to the patient such alternatives thereto and the reasonably foreseeable risk and benefits involved as a reasonable medical, dental, or podiatric practitioner under similar conditions would have disclosed, in a manner permitting the patient to make a knowledgeable evaluation.”10,19,20

New York further goes on to mandate that the plaintiff (in litigation regarding lack of infirmed consent):

“establish that a reasonably prudent person in the patient’s position would not have undergone the treatment or diagnosis if (s)he had been fully informed and that the lack of informed consent or diagnosis is a proximate cause of the injury or condition for which recovery is sought.”

Obtaining informed consent prior to a major elective operation involves a thorough explanation of the anatomy, physiology, pathology, and complications of the operation. Thus, this level of informed consent is a paradigm that is never achieved unless, perhaps, the patient is another surgeon.3 Therefore, consent is based typically upon less-complete information, because even an experienced nonsurgical physician may not really comprehend all of the potential risks of a complex operation or underlying condition.3 Thus, the legal requirements focus on important or material risks and benefits of having surgery versus nonoperative management. The patient who is not acutely ill must be engaged seriously in the discussion, and even then may not comprehend fully. Such comprehension becomes impossible for a patient with hypotension or sepsis and impaired judgment from altered cerebral blood flow and metabolism. For example, consider a middle-aged patient who presents to the emergency department with a perforated duodenal ulcer and peritonitis. Refusal of operative intervention, in this setting, most likely will result in the death of the patient. In the setting of refusal, the surgeon is obligated to assess the patient’s capacity for medical decision making by consulting a disinterested medical professional. If the individual is determined to lack capacity, then authority can be transferred to a surrogate or external legal entity,3,16 but using the court system to appoint a guardian takes time that the situation may not afford. Often the surgeon must document in writing the life-saving nature of the intervention and the inability of the patient to consent, and then proceed with the emergency operation with the knowledge of the facility’s legal representative.3

The ethics of surrogate consent are less defined if the incapacitated patient is not in a life-or-death situation. Each surgeon has to determine, within legality, the optimal, ethical solution to a dilemma.3,17 For example, consider the case of a patient with schizophrenia admitted for recurrent acute pancreatitis due to neuroleptic medications. Following partial improvement with nasogastric suction, intravenous fluids, and nutrition support, a pancreatic pseudocyst associated with ductal ectasia was identified, and a lateral pancreaticojejunostomy was recommended. The patient declined operation but his legal guardian gave permission. Should the surgeon operate against the patient’s wishes, or demur and instead offer to refer the patient to another surgeon?13

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree