Urinary Incontinence

Elena M. Umland Pharm.D.

Urinary incontinence (UI) is the involuntary loss of urine. It is not a disease, but rather a symptom of an underlying process. It is a symptom that may be significantly improved or cured in approximately 80% of affected patients (Maloney, 1995). Additionally, UI is not only a physical problem, but may also be debilitating psychosocially. It is associated with medical problems such as rashes, skin infections, pressure sores, and urinary tract infections. Psychosocial issues including depression, embarrassment, restricted social interaction, reduced activities outside the home, reduced sexual activity, and sleep disturbances may ensue (MMWR, 1995). Patients perceive UI as a very disturbing problem that restricts their activities, and the majority of these patients believe that UI could be treated (McDowell et al, 1996). Given this patient belief, in conjunction with effective treatment options, primary care providers are compelled to identify UI in their patients. This is a difficult task, because patients may not volunteer such information to their health care provider. The provider must be aware of UI and make a more concerted effort to identify its existence and its classification to make appropriate treatment choices.

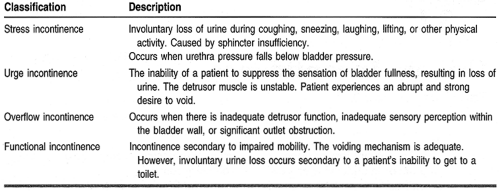

UI may be classified as either transient or chronic. Transient causes of UI include elements that form the mnemonic DIAPPERS: delirium, infection (urinary), atrophic urethritis, pharmacologic agents, psychological elements (eg, depression), excessive urine output, restricted mobility, and stool impaction (Resnick, 1996). Chronic or established UI is characterized as stress, urge, overflow, or functional (Table 34-1).

ANATOMY, PHYSIOLOGY, AND PATHOLOGY

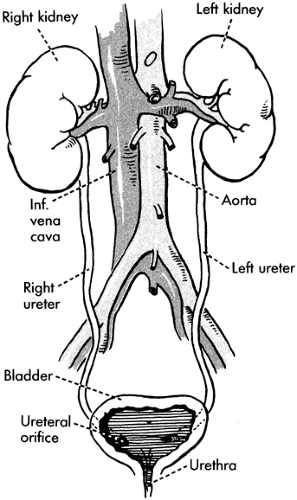

Male and female urinary systems are similar in that both consist of the following elements: the bladder, surrounded by the detrusor muscle; an internal sphincter muscle; and an external sphincter muscle. The major differences include the prostate gland and a longer urethra in males. Figure 34-1 illustrates the similarities and differences. Knowledge of the anatomy and physiology of the male and female urinary systems provides a clear understanding of the potential areas where urinary continence can be affected.

FIGURE 34-1 Bladder and urinary system anatomy. (From Rosse, C. & Gaddum-Rosse, P. (1997). Hollinshead’s Textbook of Anatomy, 5/e. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers. ) |

The detrusor muscle, responsible for the propulsive force in bladder emptying, is under parasympathetic autonomic control through the pelvic nerves (Isselbacher et al, 1995). Bladder contraction results from cholinergic stimulation. The internal and external sphincter muscles, located in the bladder outlet area, are responsible for maintaining urethral pressure. Comparably, the internal sphincter is innervated by the alpha-adrenergic pathway. Alpha-stimulation results in muscle contraction, preventing urine flow (Young & Koda-Kimble, 1995). The external sphincter is composed of striated muscle that is under voluntary control.

In the female, estrogen receptors are located in both the internal and external sphincters. Estrogen receptor stimulation, then, contributes to sphincter competence. In the absence of estrogen, as in postmenopausal women, the internal and external sphincters may not resist urine passage in situations of increased stress (eg, coughing, sneezing, climbing stairs, and other physical activities), resulting in small amounts of urine leakage. This is secondary to the lack of estrogen-stimulated competence of these sphincters.

Stress incontinence in males may result after prostate surgery in which damage to the external sphincter has occurred. Transurethral resection of the prostate may result in damage to both the internal and external sphincters such that mechanical incontinence ensues (Isselbacher et al, 1995).

Overflow incontinence may result from obstruction of the bladder neck or urethra or from neurologic damage such as spinal cord injury. Bladder outlet obstruction often occurs in men with benign prostatic hypertrophy. When enlarged, the prostate gland, which surrounds the urethra, impedes urinary outflow from the bladder. This results in symptoms such as nocturia, reduced size and force of the urinary stream, straining to void, and terminal dribbling. Detrusor instability leads to uncontrollable bladder contractions and may arise from central nervous system diseases such as cerebrovascular accidents, dementia, neoplasia, and perhaps normal-pressure hydrocephalus (Isselbacher et al, 1995).

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Although UI is not exclusive to the elderly population, it does occur most frequently in this group of patients, with 15% to 30% affected (MMWR, 1995; Barker et al, 1995; Rosenthal & McMurty, 1995). This number rises to 35% of patients in the acute-care hospital setting and up to 60% of nursing home residents (Rosenthal & McMurty, 1995). As much as 70% of cases of UI in the elderly may be attributed to detrusor instability (Isselbacher et al, 1995).

Established risk factors in UI include age, gender, and parity (Rosenthal & McMurty, 1995; Wilson & Herbison, 1995). Based on these risks, women are affected more often than men. Involuntary loss of urine secondary to activity has been reported by 50% of nulliparous women 18 to 25 years of age (Lemcke et al, 1995). Additionally, 26% of women aged 30 to 59 years have experienced UI at some time in their adult life, and often perceive it as a social or hygienic problem (Diokno, 1995).

Other potential risk factors that have not been thoroughly studied include urinary tract infection, obesity, menopause,

genitourinary surgery, lack of postpartum pelvic floor strengthening exercise, cigarette smoking, chronic illness, and certain pharmacologic agents (Rosenthal & McMurty, 1995; Wilson & Herbison, 1995). Such agents include, but are not limited to, diuretics, anticholinergics, sedatives, neuroleptics, calcium channel blockers, alcohol, and alpha-adrenergic agonists and antagonists (Resnick, 1996; Barker et al, 1995).

genitourinary surgery, lack of postpartum pelvic floor strengthening exercise, cigarette smoking, chronic illness, and certain pharmacologic agents (Rosenthal & McMurty, 1995; Wilson & Herbison, 1995). Such agents include, but are not limited to, diuretics, anticholinergics, sedatives, neuroleptics, calcium channel blockers, alcohol, and alpha-adrenergic agonists and antagonists (Resnick, 1996; Barker et al, 1995).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree