The Red Eye

Megann Young

The red eye is a common emergency department (ED) complaint that may present in isolation or in combination with other ocular or systemic disorders. The differential diagnosis is broad and includes causes ranging from benign to vision threatening.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

A red eye is produced by dilated, inflamed, superficial ocular vessels and can result from infection, inflammation, allergy, or elevated intraocular pressure. Several ocular components may be involved, most commonly the conjunctiva, but also the uveal tract, episclera, and sclera.

Conjunctivitis

Conjunctivitis is the most common cause of red eye (1,2). The conjunctiva covers the inner aspect of the lids (tarsal or palpebral conjunctiva) and reflects back on itself to cover the sclera (bulbar conjunctiva), stopping at the cornea. Infection, allergy, and irritation are the most common causes of conjunctivitis.

Infectious conjunctivitis may be viral or bacterial (Chapter 60).

Allergic conjunctivitis (3) may occur seasonally, year-round (perennial conjunctivitis), or as an isolated reaction to material in the eye (often ophthalmic medications, particularly those containing neomycin), and is more common in patients with atopic diseases such as eczema, asthma, and allergic rhinitis (2). Seasonal conjunctivitis is usually caused by airborne pollens and follows the growth cycle of the responsible plant. Perennial conjunctivitis is usually caused by allergens present in the home, particularly dust mites and animal dander. Numerous irritants may also affect the conjunctiva; common examples include dust, smoke, and chemical fumes.

Symptoms include mild irritation, itching, and watery discharge. Vision is not intrinsically affected but may be blurred by copious discharge. The conjunctivae are globally injected (both tarsal and bulbar surfaces); both eyes are equally affected (1). Allergic conjunctivitis may also present with significant conjunctival edema, termed chemosis, which appears as a marked bulging of the conjunctiva. In chronic allergic conjunctivitis, fine papillae may develop on the tarsal surface, giving a velvety appearance. Follicular hyperplasia occurs in viral or chlamydial conjunctivitis, give a cobblestone appearance.

Keratitis

Keratitis may be caused by bacterial, viral, fungal, and UV sources. Infectious keratitis is discussed in Chapter 60. Photokeratitis, caused by UV light exposure, is characterized by foreign body sensation, photophobia, and superficial punctate fluorescein uptake on slit lamp exam; management is supportive, and ophthalmology referral is only required if symptoms persist beyond 48 to 72 hours.

Uveitis

The uveal tract consists of the iris, ciliary body, and choroid. Uveitis is classified as anterior, intermediate, and posterior. Only anterior uveitis typically produces a visibly red eye; it includes iritis and iridocyclitis (inflammation involving the iris and ciliary body). Approximately 50% of cases are idiopathic; most of the remainder are immune mediated (4,5), and a few are infectious.

Typical symptoms include pain (which may radiate to the temple or worsen with extraocular movements), photophobia, consensual photophobia (light in the unaffected eye produces pain in the red eye), and decreased vision. Physical findings include decreased visual acuity, pupillary constriction, and fine vascular dilation concentrated in the area around the cornea (perilimbal or ciliary flush). The large, dilated vessels typical of conjunctivitis are absent. On slit-lamp examination, there are cells and flare in the aqueous humor, which in severe cases may contain fibrin clot or even pus (hypopyon).

Episcleritis

The episclera is a thin, membranous layer between the conjunctiva and sclera. Inflammation is usually idiopathic but is sometimes associated with immune-mediated disorders (6,7). It occurs mainly in young adults, most commonly women. Patients have mild discomfort, tearing, and an erythematous, injected patch on the globe. The injected area is usually localized, occupying less than half of the visible globe. Episcleritis poses no threat to vision and is self-limited, usually resolving within 2 to 3 weeks (2).

Scleritis

Scleritis is an inflammation of the sclera (the thick, white connective tissue covering the anterior surface of the globe). Inflammation (7) is often idiopathic, but about 50% are associated with systemic diseases (1), often immune-mediated disorders. Scleritis is most common between ages 30 and 60 and is somewhat more common in women. Within several years of an acute attack, up to one-third of patients suffer significant loss of visual acuity. Pain is severe, deep, and typically described as “boring”; pain may be worse with extraocular movements. The pain often interferes with sleep and may radiate to the forehead or jaw. The eye is diffusely hyperemic, often violaceous; sometimes only one quadrant is involved. The palpebral conjunctiva is not inflamed. An identifying feature of scleritis is tenderness of the globe to palpation. An avascular-appearing area amid the hyperemia suggests necrotizing scleritis, which can progress to globe perforation.

Acute Angle-Closure Glaucoma

A rapid increase in intraocular pressure results in severe pain, hyperemia, and impaired vision with a pupil that is classically midposition and poorly reactive (Chapter 61).

Corneal Abrasion and Foreign Body

Significant eye trauma is typically clinically obvious; patients present with complaint of injury rather than red eye. However, minor corneal abrasions and foreign bodies may be present without recognized trauma, particularly in young children and infants (Chapter 57).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

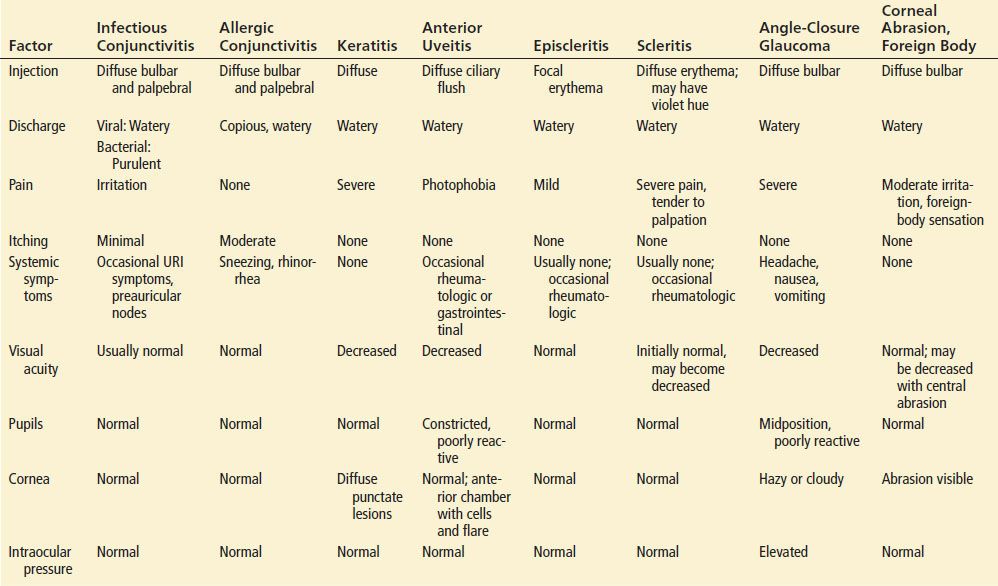

The differential for the red eye may be best summarized in tabular form (Table 56.1). Other disorders that might produce scleral injection include chemical irritation or infections of the surrounding structures.

TABLE 56.1

Differential Diagnosis of Red Eye